- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

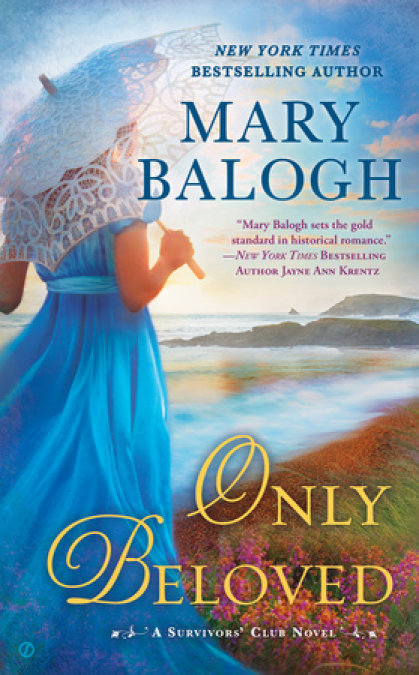

From the legendary New York Times bestselling author of Only a Kiss and Only a Promise comes the final book in the rapturous Survivor's Club series--as the future of one man lies within the heart of a lost but never-forgotten love...

For the first time since the death of his wife, the Duke of Stanbrook is considering remarrying and finally embracing happiness for himself. With that thought comes the treasured image of a woman he met briefly a year ago and never saw again.

Dora Debbins relinquished all hope to marry when a family scandal left her in charge of her younger sister. Earning a modest living as a music teacher, she's left with only an unfulfilled dream. Then one afternoon, an unexpected visitor makes it come true.

For both George and Dora that brief first encounter was as fleeting as it was unforgettable. Now is the time for a second chance. And while even true love comes with a risk, who are two dreamers to argue with destiny?

Release date: May 3, 2016

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Only Beloved

Mary Balogh

George Crabbe, Duke of Stanbrook, stood at the foot of the steps outside his London home on Grosvenor Square, his right hand still raised in farewell

even though the carriage bearing his two cousins on their journey home to Cumberland was already out of sight. They had made an early start despite the

fact that a few forgotten items, or items they feared they had forgotten, had twice delayed their departure while first a maid and then the housekeeper

herself hurried upstairs to look in their vacated rooms just in case.

Margaret and Audrey were sisters and his second cousins to be precise. They had come to London for the wedding of Imogen Hayes, Lady Barclay, to Percy,

Earl of Hardford. Audrey was the bride’s mother. Imogen had stayed at Stanbrook House too until her wedding two days ago, partly because she was a

relative, but mainly because there was no one in the world George loved more. There were five others he loved equally well, it was true, though Imogen

was the only woman and the only one related to him. The seven of them, himself included, were the members of the self-styled Survivors’ Club.

A little over eight years ago George had made the decision to open Penderris Hall, his country seat in Cornwall, as a hospital and recovery center for

military officers who had been severely wounded in the Napoleonic Wars and needed more intense and more extended care than could be provided by their

families. He had hired a skilled physician and other staff members willing to act as nurses, and he had handpicked the patients from among those

recommended to him. There had been more than two dozen in all, most of whom had survived and returned to their families or regiments after a few weeks

or months. But six had remained for three years. Their injuries had varied widely. Not all had been physical. Hugo Emes, Lord Trentham, for example,

had been brought there without a scratch on his body but out of his mind and with a straitjacket restraining him from doing violence to himself or

others.

A deep bond had developed among the seven of them, an attachment too strong to be severed even after they left Penderris and returned to their separate

lives. Those six people meant more to George than anyone else still living—though perhaps that was not quite accurate, for he was dearly fond too of

his only nephew, Julian, and of Julian’s wife, Philippa, and their infant daughter, Belinda. He saw them with fair frequency too and always with

pleasure. They lived only a few miles from Penderris. Love, of course, did not move in hierarchies of preference. Love manifested itself in a thousand

different ways, all of which were love in its entirety. A strange thing, that, if one stopped to think about it.

He lowered his hand, feeling suddenly foolish to be waving farewell to empty air, and turned back to the house. A footman hovered at the door, no doubt

anxious to close it. He was probably shivering in his shoes. A brisk early morning breeze was blowing across the square directly at him though there

was plenty of blue sky above along with some scudding clouds in promise of a lovely mid-May day.

He nodded to the young man and sent him to the kitchen to fetch coffee to the library.

The morning post had not arrived yet, he could see when he entered the room. The surface of the large oak desk before the window was bare except for a

clean blotter and an inkpot and two quill pens. There would be the usual pile of invitations when the post did arrive, it being the height of the

London Season. He would be required to choose among balls and soirees and concerts and theater groups and garden parties and Venetian breakfasts and

private dinners and a host of other entertainments. Meanwhile his club offered congenial company and diversion, as did Tattersall’s and the races and

his tailor and boot maker. And if he did not wish to go out, he was surrounded in this very room by bookshelves that reached from floor to ceiling,

interrupted only by doors and windows. If there was room for one more book on any of the shelves, he would be surprised. There were even a few books

among them that he had not yet read but would doubtless enjoy.

It was a pleasant feeling to know that he might do whatever he wished with his time, even nothing at all if he so chose. The weeks leading up to

Imogen’s wedding and the few days since had been exceedingly busy ones and had allowed him very little time to himself. But he had enjoyed the busyness

and had to admit that there was a certain flatness mingled with his pleasure this morning in the knowledge that yet again he was alone and free and

beholden to no one. The house seemed very quiet, even though his cousins had not been noisy or demanding houseguests. He had enjoyed their company far

more than he had expected. They were virtual strangers, after all. He had not seen either sister for a number of years before this past week.

Imogen herself was the closest of friends but could have caused some upheaval due to her impending nuptials. She had not. She was not a fussy bride in

the least. One would hardly have known, in fact, that she was preparing for her wedding, except that there had been a new and unfamiliar glow about her

that had warmed George’s heart.

The wedding breakfast had been held at Stanbrook House. He had insisted upon it, though both Ralph and Flavian, their fellow Survivors, had offered to

host it too. Half the ton had been present, filling the ballroom almost to overflowing and inevitably spilling out into other rooms in the

hours following the meal and all the speeches. And breakfast was certainly a misnomer, since very few of the guests had left until late in the

evening.

George had enjoyed every moment.

But now the festivities were all over, and after the wedding Imogen had left with Percy for a honeymoon in Paris. Now Audrey and Margaret were gone

too, although before leaving they had hugged him tightly, thanked him effusively for his hospitality, and begged him to come and stay with them in

Cumberland sometime soon.

There was a strong sense of finality about this morning. There had been a flurry of weddings in the last two years, including those of all the

Survivors and George’s nephew, all the people most dear to him in the world. Imogen had been the last of them—with the exception of himself, of course.

But he hardly counted. He was forty-eight years old and, after eighteen years of marriage, he had been a widower for more than twelve years.

He was glad to see that the fire in the library had been lit. He had got chilled standing outside. He took the chair to one side of the fireplace and

held out his hands to the blaze. The footman brought the tray a few minutes later, poured his coffee, and set the cup and saucer on the small table

beside him along with a plate of sweet biscuits that smelled of butter and nutmeg.

“Thank you.” George added milk and a little sugar to the dark brew and remembered for no apparent reason how it had always irritated his wife that he

acknowledged even the slightest service paid him by a servant. Doing so would only lower him in their esteem, she had always explained to him.

It seemed almost incredible that all six of his fellow Survivors had married within the past two years. It was as if they had needed the three years

after leaving Penderris to adjust to the outside world again after the sheltered safety the house had provided during their recovery, but had then

rushed joyfully back into full and fruitful lives. Perhaps, having hovered for so long close to death and insanity, they had needed to celebrate life

itself. He was quite certain too that they had all made happy marriages. Hugo and Vincent each had a child already, and there was another on the way

for Vincent and Sophia. Ralph and Flavian were also in expectation of fatherhood. Even Ben, another of their number, had whispered two days ago that

Samantha had been feeling queasy for the past few mornings and was hopeful that it was in a good cause.

It was all thoroughly heartwarming to the man who had opened his home and his heart to men—and one woman—who had been broken by war and might have

remained forever on the fringes of their own lives if he had not done so. If they had survived at all, that was.

George looked speculatively at the biscuits but did not take one. He picked up his coffee cup, however, and warmed his hands about it, ignoring the

handle.

Was it downright contrary of him to be feeling ever so slightly depressed this morning? Imogen’s wedding had been a splendidly festive and happy

occasion. George loved to see her glow, and, despite some early misgivings, he liked Percy too and thought it probable he was the perfect husband for

her. George was very fond of the wives of the other Survivors too. In many ways he felt like a smugly proud father who had married off his brood to so

many happily-ever-afters.

Perhaps that was the trouble, though. For he was not their father, was he? Or anyone else’s for that matter. He frowned into his coffee, considered

adding more sugar, decided against doing so, and took another sip. His only son had died at the age of seventeen during the early years of the

Peninsular Wars, and his wife—Miriam—had taken her own life just a few months later.

He was, George thought as he gazed sightlessly into his cup, very much alone—though no more so now than he had been before Imogen’s wedding and all the

others. Julian was his late brother’s son, not his own, and his six fellow Survivors had all left Penderris Hall five years ago. Although the bonds of

friendship had remained strong and they all gathered for three weeks every year, usually at Penderris, they were not literally family. Even Imogen was

only his second cousin once removed.

They had moved on with their lives, those six, and left him behind. And what a blasted pathetic, self-pitying thought that was.

George drained his cup, set it down none too gently on the saucer, put both on the tray, and got restlessly to his feet. He moved behind the desk and

stood looking out through the window onto the square. It was still early enough that there was very little activity out there. The clouds were sparser

than they had been earlier, the sky a more uniform blue. It was the sort of day designed to lift the human spirit.

He was lonely, damn it. To the marrow of his bones and the depths of his soul.

He almost always had been.

His adult life had begun brutally early. He had taken up a military commission with great excitement at the age of seventeen, having convinced his

father that a career in the army was what he wanted more than anything else in life. But just four months later he had been summoned back home when his

father had learned that he was dying. Before he turned eighteen, George had sold out his cornetcy, married Miriam, lost his father, and succeeded him

to the title Duke of Stanbrook himself. Brendan had been born before he was nineteen.

It seemed to George, looking back, that all his adult life he had never been anything but lonely, with the exception of that brilliant flaring of

exuberant joy he had experienced all too briefly when he was with his regiment. And there had been a few years with Brendan . . .

He clasped his hands behind his back and remembered too late that he had told Ralph and Ben yesterday that he would join them for a ride in Hyde Park

this morning if his cousins made the early departure they had planned. All the Survivors had come to London for Imogen’s wedding, and all were still

here, except Vincent and Sophia, who had left for Gloucestershire yesterday. They preferred being at home, for Vincent was blind and felt more

comfortable in the familiar surroundings of Middlebury Park. And the bride and groom, of course, were on their way to Paris.

There was no reason for George to feel lonely and there would be none even after the other four had left London and returned home. There were other

friends here, both male and female. And in the country there were neighbors he considered friends. And there were Julian and Philippa.

But he was lonely, damn it. And the thing was that he had only recently admitted it to himself—only during the past week, in fact, amid all

the happy bustle of preparations for the final Survivor wedding. He had even asked himself in some alarm if he resented Percy for winning Imogen’s

heart and hand, for being able to make her laugh again and glow. He had asked himself if perhaps he loved her himself. Well, yes, he did, he had

concluded after some frank consideration. There was absolutely no doubt about it—just as there was no doubt that his love for her was not that

kind of love. He loved her exactly as he loved Vincent and Hugo and the rest of them—deeply but purely platonically.

During the last few days he had toyed with the idea of hiring a mistress again. He had done so occasionally down the years. A few times he had even

indulged in discreet affairs with ladies of his own class—all widows for whom he had felt nothing but liking and respect.

He did not want a mistress.

Last night he had lain awake, staring up at the shadowed canopy above his bed, unable to coax his mind to relax and his body to sleep. It had been one

of those nights during which, for no discernible reason, sleep eluded him, and the notion had popped into his head, seemingly from nowhere, that

perhaps he ought to marry. Not for love or issue—he was too old for either romance or fatherhood. Not that he was physically too old for the latter,

but he did not want a child, or children, at Penderris again. Besides, he would have to marry a young woman if he wanted to populate his nursery, and

the thought of marrying someone half his age held no appeal. It might for many men, but he was not one of them. He could admire the young beauties who

crowded fashionable ballrooms during the Season each spring, but he felt not the slightest desire to bed any of them.

What had occurred to his mind last night was that marriage might bring him companionship, possibly a real friendship. Perhaps even someone in the

nature of a soul mate. And, yes, someone to lie beside him in bed at night to soothe his loneliness and provide the regular pleasures of sex.

He had been celibate a little too long for comfort.

Two horses were clopping along the other side of the square, he could see, led by a groom on horseback. Both horses bore sidesaddles. The door of the

Rees-Parry house directly opposite opened, and the two young daughters of the house stepped out and were helped into the saddle by the groom. Both

girls wore smart riding habits. The faint sounds of feminine laughter and high spirits carried across the square and through the closed window of the

library. They rode off in evident high spirits, the groom following a respectful distance behind them.

Youth could be delightful to behold, but he felt no yearning to be a part of it.

The idea that had come to him last night had not been purely hypothetical. It had come complete with the image of a particular woman, though why her he

could not explain to himself. He scarcely knew her, after all, and had not seen her for more than a year. But there she had been, quite vivid in his

mind’s eye while he had been thinking that maybe he ought to consider marrying again. Marrying her. It had seemed to him that she would be the

perfect—the only—choice.

He had dozed off eventually and woken early to take breakfast with his cousins before seeing them on their way. Only now had he remembered those

bizarre nighttime yearnings. Surely he must have been at least half asleep and half dreaming. It would be madness to tie himself down with a wife

again, especially one who was a virtual stranger. What if she did not suit him after all? What if he did not suit her? An unhappy marriage would be

worse than the loneliness and emptiness that sometimes conspired to drag down his spirits.

But now the same thoughts were back. Why the devil had he not gone riding? Or to White’s Club? He could have had his coffee there and occupied himself

with the congenial conversation of male acquaintances or distracted himself with a perusal of the morning papers.

Would she have him if he asked? Was it conceited of him to believe that she would indeed? Why, after all, would she refuse him unless perhaps she was

deterred by the fact that she did not love him? But she was no longer a young woman, her head stuffed with romantic dreams. She was probably as

indifferent to romance as he was himself. He had much to offer any woman, even apart from the obvious inducements of a lofty title and fortune. He had

a steady character to offer as well as friendship and . . . Well, he had marriage to offer. She had never been married.

Would he merely be making an idiot of himself, though, if he married again now when he was well into middle age? But why? Men his age and older were

marrying all the time. And it was not as though he had his sights fixed upon some sweet young thing fresh out of the schoolroom. That would be

pathetic. He would be seeking comfort with a mature woman who would perhaps welcome a similar comfort into her own life.

It was absurd to think that he was too old. Or that she was. Surely everyone was entitled to some companionship, some contentment in life even when

youth was a thing of the past. He was not seriously considering doing it, though, was he?

A tap on the library door preceded the appearance in the room of a youngish man carrying a bundle of letters.

“Ethan?” George nodded to his secretary. “Anything of burning interest or vast moment?”

“No more than the usual, Your Grace,” Ethan Briggs said as he divided the pile in two and set each down on the desk. “Business and social.” He

indicated each pile in turn, as he usually did.

“Bills?” George jutted his chin in the direction of the business pile.

“One from Hoby’s for a pair of riding boots,” his secretary said, “and various wedding expenses.”

“And they need my inspection?” George looked pained. “Pay them, Ethan.”

His secretary scooped up the first pile.

“Take the others away too,” George said, “and send polite refusals.”

“To all of them, Your Grace?” Briggs raised his eyebrows. “The Marchioness of—”

“All,” George said. “And everything that comes for the next several days until you receive further instructions from me. I am leaving town.”

“Leaving?” Again the raised eyebrows.

Briggs was an efficient, thoroughly reliable secretary. He had been with the Duke of Stanbrook for almost six years. But no one is perfect, George

mused. The man had a habit of repeating certain words his employer addressed to him as though he could not quite believe he had heard correctly.

“But there is your speech in the House of Lords the day after tomorrow, Your Grace,” he said.

“It will keep.” George waved a dismissive hand. “I will be leaving tomorrow.”

“For Cornwall, Your Grace?” Briggs asked. “Do you wish me to write to inform the housekeeper—”

“Not for Penderris Hall,” George said. “I will be back . . . well, when I return. In the meantime, pay my bills and refuse my invitations and do

whatever else I keep you busy doing.”

His secretary picked up the remaining pile from the desk, acknowledged his employer with a respectful bow, and left the room.

So he was going, was he? George asked himself. To propose marriage to a lady he scarcely knew and had not even seen in a longish while?

How did one propose marriage? The last time he had been seventeen years old and it had been a mere formality, both their fathers having agreed upon the

match, come to terms, and signed the contract. A mere son’s and daughter’s wishes and sensibilities had not been taken into consideration or even

consulted, especially when one of the fathers already had a foot in the grave and was in some hurry to see his son settled. At least this time George

knew the lady a little better than he had known Miriam. He knew what she looked like at least and what her voice sounded like. The first time

he had set eyes upon Miriam had been on the occasion of his proposal, conducted with stammering formality under the stern gaze of her father and his

own.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...