- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

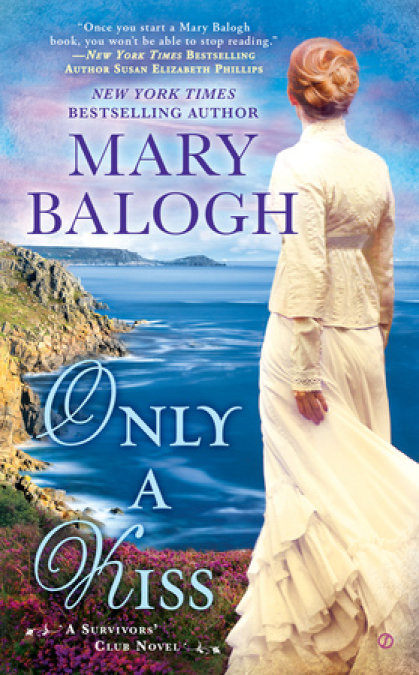

Synopsis

The Survivors' Club: Six men and one woman, injured in the Napoleonic Wars, their friendships forged in steel and loyalty. But for one, her trials are not over.... Since witnessing the death of her husband during the wars, Imogen, Lady Barclay, has secluded herself in the confines of Hardford Hall, their home in Cornwall. The new owner has failed to take up his inheritance, and Imogen desperately hopes he will never come to disturb her fragile peace.

Percival Hayes, Earl of Hardford, has no interest in the wilds of Cornwall, but when he impulsively decides to pay a visit to his estate there, he is shocked to discover that it is not the ruined heap he had expected. He is equally shocked to find the beautiful widow of his predecessor's son living there. Soon Imogen awakens in Percy a passion he has never thought himself capable of feeling. But can he save her from her misery and reawaken her soul? And what will it mean for him if he succeeds?

Release date: September 1, 2015

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Only a Kiss

Mary Balogh

1

Percival William Henry Hayes, Earl of Hardford, Viscount Barclay, was hugely, massively, colossally bored. All of which descriptors were basically the same thing, of course, but really he was bored to the marrow of his bones. He was almost too bored to heave himself out of his chair in order to refill his glass at the sideboard across the room. No, he was too bored. Or perhaps just too drunk. Maybe he had even gone as far as drinking the ocean dry.

He was celebrating his thirtieth birthday, or at least he had been celebrating it. He suspected that by now it was well past midnight, which fact would mean that his birthday was over and done with, as were his careless, riotous, useless twenties.

He was lounging in his favorite soft leather chair to one side of the hearth in the library of his town house, he was pleased to observe, but he was not alone, as he really ought to be at this time of night, whatever the devil time that was. Through the fog of his inebriation he seemed to recall that there had been celebrations at White’s Club with a satisfyingly largish band of cronies, considering the fact that it was very early in February and not at all a fashionable time to be in London.

The noise level, he remembered, had escalated to the point at which several of the older members had frowned in stern disapproval—old fogies and fossils, the lot of them—and the inscrutable waiters had begun to show cracks of strain and indecision. How did one chuck out a band of drunken gentlemen, some of them of noble birth, without giving permanent offense to them and to all their family members to the third and fourth generation past and future? But how did one not do the chucking when inaction would incur the wrath of the equally nobly born fogies?

Some amicable solution must have been found, however, for here he was in his own home with a small and faithful band of comrades. The others must have taken themselves off to other revelries, or perhaps merely to their beds.

“Sid.” He turned his head on the back of the chair without taking the risk of raising it. “In your considered opinion, have I drunk the ocean dry tonight? It would be surprising if I had not. Did not someone dare me?”

The Honorable Sidney Welby was gazing into the fire—or what had been the fire before they had let it burn down without shoveling on more coal or summoning a servant to do it for them. His brow furrowed in thought before he delivered his answer. “Couldn’t be done, Perce,” he said. “Replenished consh—constantly by rivers and streams and all that. Brooks and rills. Fills up as fast as it empties out.”

“And it gets rained upon too, cuz,” Cyril Eldridge added helpfully, “just as the land does. It only feels as if you had drunk it dry. If it is dry, though, it having not rained lately, we all had a part in draining it. My head is going to feel at least three times its usual size tomorrow morning, and dash it all but I have a strong suspicion I agreed to escort m’sisters to the library or some such thing, and as you know, Percy, m’mother won’t allow them to go out with just a maid for company. They always insist upon leaving at the very crack of dawn too, lest someone else arrive before them and carry off all the books worth reading. Which is not a large number, in my considered opinion. And what are they all doing in town this early, anyway? Beth is not making her come-out until after Easter, and she cannot need that many clothes. Can she? But what does a brother know? Nothing whatsoever if you listen to m’sisters.”

Cyril was one of Percy’s many cousins. There were twelve of them on the paternal side of the family, the sons and daughters of his father’s four sisters, and twenty-three of them at last count on his mother’s side, though he seemed to remember her mentioning that Aunt Doris, her youngest sister, was in a delicate way again for about the twelfth time. Her offspring accounted for a large proportion of those twenty-three, soon to be twenty-four. All of the cousins were amiable. All of them loved him, and he loved them all, as well as all the uncles and aunts, of course. Never had there been a closer-knit, more loving family than his, on both sides. He was, Percy reflected with deep gloom, the most fortunate of mortals.

“The bet, Perce,” Arnold Biggs, Viscount Marwood, added, “was that you could drink Jonesey into a coma before midnight—no mean feat. He slid under the table at ten to twelve. It was his snoring that finally made us decide that it was time to leave White’s. It was downright distracting.”

“And so it was.” Percy yawned hugely. That was one mystery solved. He raised his glass, remembered that it was empty, and set it down with a clunk on the table beside him. “Devil take it but life has become a crashing bore.”

“You will feel better tomorrow after the shock of turning thirty today has waned,” Arnold said. “Or do I mean today and yesterday? Yes, I do. The small hand of the clock on your mantel points to three, and I believe it. The sun is not shining, however, so it must be the middle of the night. Though at this time of the year it is always the middle of the night.”

“What do you have to be bored about, Percy?” Cyril asked, sounding aggrieved. “You have everything a man could ask for. Everything.”

Percy turned his mind to a contemplation of his many blessings. Cyril was quite right. There was no denying it. In addition to the aforementioned loving extended family, he had grown up with two parents who adored him as their only son—their only child as it had turned out, though they had apparently made a valiant effort to populate the nursery with brothers and sisters for him. They had lavished everything upon him that he could possibly want or need, and they had had the means with which to do it in style.

His paternal great-grandfather, as the younger son of an earl and only the spare of his generation instead of the heir, had launched out into genteel trade and amassed something of a fortune. His son, Percy’s grandfather, had made it into a vast fortune and had further enhanced it when he married a wealthy, frugal woman, who reputedly had counted every penny they spent. Percy’s father had inherited the whole lot except for the more-than-generous dowries bestowed upon his four sisters upon their marriages. And then he had doubled and tripled his wealth through shrewd investments, and he in his turn had married a woman who had brought a healthy dowry with her.

After his father’s death three years ago, Percy had become so wealthy that it would have taken half the remainder of his life just to count all the pennies his grandmother had so carefully guarded. Or even the pounds for that matter. And there was Castleford House, the large and prosperous home and estate in Derbyshire that his grandfather had bought, reputedly with a wad of banknotes, to demonstrate his consequence to the world.

Percy had looks too. There was no point in being overmodest about the matter. Even if his glass lied or his perception of what he saw in that glass was off, there was the fact that he turned admiring, sometimes envious, heads wherever he went—both male and female. He was, as a number of people had informed him, the quintessential tall, dark, handsome male. He enjoyed good health and always had, knock on wood—he raised his hand and did just that with the knuckles of his right hand, banging on the table beside him and setting the empty glass and Sid to jumping. And he had all his teeth, all of them decently white and in good order.

He had brains. After being educated at home by three tutors because his parents could not bear to send him away to school, he had gone up to Oxford to study the classics and had come down three years later having achieved a double first degree in Latin and Ancient Greek. He had friends and connections. Men of all ages seemed to like him, and women . . . Well, women did too, which was fortunate, as he liked them. He liked to charm them and compliment them and turn pages of music for them and dance with them and take them walking and driving. He liked to flirt with them. If they were widows and willing, he liked to sleep with them. And he had developed an expertise in avoiding all of the matrimonial traps that were laid for him at every turn.

He had had a number of mistresses—though he had none at the moment—all of them exquisitely lovely and marvelously skilled, all of them expensive actresses or courtesans much coveted by his peers.

He was strong and fit and athletic. He enjoyed riding and boxing and fencing and shooting, at all of which he excelled and all of which had left him somehow restless lately. He had taken on more than his fair share of challenges and dares over the years, the more reckless and dangerous the better. He had raced his curricle to Brighton on three separate occasions, once in both directions, and taken the ribbons of a heavily laden stagecoach on the Great North Road after bribing the coachman . . . and sprung the horses. He had crossed half of Mayfair entirely upon rooftops and occasionally the empty air between them, having been challenged to accomplish the feat without touching the ground or making use of any conveyance that touched the ground. He had crossed almost every bridge across the River Thames within the vicinity of London—from underneath. He had strolled through some of the most notoriously cutthroat rookeries of London in full evening finery with no weapon more deadly than a cane—not a sword cane. He had got an exhilarating fistfight against three assailants out of that last exploit after his cane snapped in two, and one great black eye in addition to murder done to his finery, much to the barely contained grief of his valet.

He had dealt with irate brothers and brothers-in-law and fathers, always unjustly, because he was always careful not to compromise virtuous ladies or raise expectations he had no intention of fulfilling. Occasionally those confrontations had resulted in fisticuffs too, usually with the brothers. Brothers, in his experience, tended to be more hotheaded than fathers. He had fought one duel with a husband who had not liked the way Percy smiled at his wife. Percy had not even spoken with her or danced with her. He had smiled because she was pretty and was smiling at him. What was he to have done? Scowled at her? The husband had shot first on the appointed morning, missing the side of Percy’s head by a quarter of a mile. Percy had shot back, missing the husband’s left ear by two feet—he had intended it to be one foot, but at the last moment had erred on the side of caution.

And, if all that were not enough blessing for one man, he had the title. Titles. Plural. The old Earl of Hardford, also Viscount Barclay, had been a sort of relative of Percy’s, courtesy of that great-great-grandfather of his. There had been a family quarrel and estrangement involving the sons of that ancestor, and the senior branch, which bore the title and was ensconced in a godforsaken place near the toe of Cornwall, had been ignored by the younger branch ever after. The most recent earl of that older branch had had a son and heir, apparently, but for some unfathomable reason, since there was no other son to act as a spare, that son had gone off to Portugal as a military officer to fight against old Boney’s armies and had got himself killed for his pains.

All the drama of such a family catastrophe had been lost upon the junior branch, which had been blissfully unaware of it. But it had all come to light when the old earl turned up his toes a year almost to the day after Percy’s father died, and it turned out that Percy was the sole heir to the titles and the crumbling heap in Cornwall. At least, he assumed it was probably crumbling, since the estate there certainly did not appear to be generating any vast income. Percy had taken the title—he had had no choice really, and actually it had rather tickled his fancy, at least at first, to be addressed as Hardford or, better still, as my lord instead of as plain Mr. Percival Hayes. He had accepted the title and ignored the rest—well, most of the rest.

He had been admitted to the House of Lords with due pomp and ceremony, and had delivered his maiden speech on one memorable afternoon after a great deal of writing and rewriting and rehearsing and rerehearsing and second and third and forty-third thoughts and nights of vivid dreams that had bordered upon nightmare. He had sat down at the end of it to polite applause and the relief of knowing that never again did he have to speak a word in the House unless he chose to do so. He had actually so chosen on a number of occasions without losing a wink of sleep.

He was on hailing terms with the king and all the royal dukes, and had been more sought after than ever socially. He had already patronized the best tailors and boot makers and haberdashers and barbers and such, but he was bowed and scraped to at a wholly elevated level after he became m’lord. He had always been popular with them all, since he was that rarity among gentlemen of the ton—a man who paid his bills regularly. He still did, to their evident astonishment. He spent the spring months in London for the parliamentary session and the Season, and the summer months on his own estate or at one of the spas, and the autumn and winter months at home or at one of the various house parties to which he was always being invited, shooting, fishing, hunting according to whichever was most in season, and socializing. The only reason he was in London at the start of February this year was that he had imagined the sort of thirtieth birthday party his mother would want to organize for him at Castleford. And how did one say no to the mother one loved? One did not, of course. One retreated to town instead like a naughty schoolboy hiding out from the consequences of some prank.

Yes. To summarize. He was the most fortunate man on earth. There was not a cloud in his sky and never really had been. It was one vast, cloudless, blue expanse of bliss up there. A brooding, wounded, darkly compelling hero type he was not. He had never done anything to brood over or anything truly heroic, which was a bit sad, really. The heroic part, that was.

Every man ought to be a hero at least once in his life.

“Yes, everything,” he agreed with a sigh, referring to what his cousin had said a few moments ago. “I do have it all, Cyril. And that, dash it all, is the trouble. A man who has everything has nothing left to live for.”

One of his worthy tutors would have rapped him sharply over the knuckles with his ever-present cane for ending a sentence with a preposition.

“Philosh—philosophophy at three o’clock in the morning?” Sidney said, lurching to his feet in order to cross to the sideboard. “I should go home before you tie our brains in a knot, Perce. We celebrated your birthday in style at White’s. We should then have trotted home to bed. How did we get here?”

“In a hackney carriage,” Arnold reminded him. “Or did you mean why, Sid? Because we were about to get kicked out and Jonesey was snoring and you suggested we come here and Percy voiced no protest and we all thought it was the brightest idea you had had in a year or longer.”

“I remember now,” Sidney said as he filled his glass.

“How can you be bored, Percy, when you admit to having everything?” Cyril asked, sounding downright rattled now. “It seems dashed ungrateful to me.”

“It is ungrateful,” Percy agreed. “But I am mightily bored anyway. I may be reduced to running down to Hardford Hall. The wilds of Cornwall, no less. It would at least be something I have never done before.”

Now what had put that idea into his head?

“In February?” Arnold grimaced. “Don’t make any rash decisions until April, Perce. There will be more people in town by then, and the urge to run off somewhere else will vanish without a trace.”

“April is two months away,” Percy said.

“Hardford Hall!” Cyril said in some revulsion. “The place is in the back of beyond, is it not? There will be no action for you there, Percy. Nothing but sheep and empty moors, I can promise you. And wind and rain and sea. It would take you a week just to get there.”

Percy raised his eyebrows. “Only if I were to ride a lame horse,” he said. “I do not possess any lame horses, Cyril. I’ll have all the cobwebs swept out of the rafters in the house when I get there, shall I, and invite you all down for a big party?”

“You are not sherious, are you, Perce?” Sidney asked without even correcting himself.

Was he? Percy gave the matter some thought, admittedly fuzzily. The Session and the Season would swing into action as soon as Easter was done with, and apart from a few new faces and a few inevitable changes in fashion to ensure that everyone kept trotting off to tailors and modistes, there would be absolutely nothing new to revive his spirits. He was getting a bit old for all the dares and capers that had kept him amused through most of his twenties. If he went home to Derbyshire instead of staying here, his mother would as like as not decide to organize a belated birthday party in his honor, heaven help him. He might attempt to involve himself in estate business if he went there, he supposed, but he would soon find himself, as usual, being regarded with pained tolerance by his very competent steward. The man quite intimidated him. He seemed a bit like an extension of those three worthy tutors of Percy’s boyhood.

Why not go to Cornwall? Perhaps the best answer to boredom was not to try running from it, but rather to dash toward it, to do all in one’s power to make it even worse. Now there was a thought. Perhaps he ought not to try thinking when he was inebriated, though. Certainly it was not wise to try planning while the rational mind was in such an impaired condition. Or to talk about his plans with men who would expect him to turn them into action just because that was what he always did. He might very well want to change his mind when morning and sobriety came. No, better make that afternoon.

“Why would I not be serious?” he asked of no one in particular. “I have owned the place for two years but have never seen it. I ought to put in an appearance sooner rather than later—or in this case, later rather than sooner. Lord of the manor and all that. Going there will pass some time, at least until things liven up a bit in London. Perhaps after a week or two I will be happy to dash back here, counting my blessings with every passing mile. Or—who knows? Perhaps I will fall in love with the place and remain there forever and ever, amen. Perhaps I will be happy to be Hardford of Hardford Hall. It does not have much of a ring to it, though, does it? You would think the original earl would have had the imagination to think up a better name for the heap, would you not? Heap Hall, perhaps? Hardford of Heap Hall?”

Lord, he was drunk.

Three pairs of eyes were regarding him with varying degrees of incredulity. The owners of those eyes were all also looking slightly disheveled and generally the worse for wear.

“If you will all excuse me,” Percy said, pushing himself abruptly to his feet and discovering that at least he was not falling-over drunk. “I had better write to someone at Hardford and warn them to start sweeping cobwebs. The housekeeper, if there is one. The butler, if there is one. The steward, if . . . Yes, by Jove, there is one of those. He sends me a five-line report in microscopic handwriting regularly every month. I will write to him. Warn him to purchase a large broom and find someone who knows how to use it.”

He yawned until his jaws cracked and stayed on his feet until he had seen his friends on their way through the front door and down the steps into the square beyond. He watched to make sure they all remained on their pins and found their way out of the square.

He sat down to write his letter before his purpose cooled, and then another to his mother to explain where he was going. She would worry about him if he simply disappeared off the face of the earth. He left both missives on the tray in the hall to be sent off in the morning and dragged himself upstairs to bed. His valet was waiting for him in his dressing room, despite having been told that he need not do so. The man enjoyed being a martyr.

“I am drunk, Watkins,” Percy announced, “and I am thirty years old. I have everything, as my cousin has just reminded me, and I am so bored that getting out of bed in the mornings is starting to seem a pointless effort, for I just have to get back into it the next night. Tomorrow—or, rather, today—you may pack for the country. We are off to Cornwall. To Hardford Hall. The earl’s seat. I am the earl.”

“Yes, m’lord,” Watkins said, the aloof dignity of his expression unchanging. He probably would have said the same and looked the same if Percy had announced that they were off to South America to undertake an excursion up the River Amazon in search of headhunters. Were there headhunters on the Amazon?

No matter. He was off to the toe of Cornwall. He must be mad. At the very least. Perhaps sobriety would bring a return of sanity.

Tomorrow.

Or did he mean later today? Yes, he did. He had just said as much to Watkins.

2

Imogen Hayes, Lady Barclay, was on her way home to Hardford Hall from the village of Porthdare two miles away. Usually she rode the distance or drove herself in the gig, but today she had decided she needed exercise. She had walked down to the village along the side of the road, but she had chosen to take the cliff path on the return. It would add an extra half mile or so to the distance, and the climb up from the river valley in which the village was situated was considerably steeper than the more gradual slope of the road. But she actually enjoyed the pull on her leg muscles and the unobstructed views out over the sea to her right and back behind her to the lower village with its fishermen’s cottages clustered about the estuary and the boats bobbing on its waters.

She enjoyed the mournful cry of the seagulls, which weaved and dipped both above and below her. She loved the wildness of the gorse bushes that grew in profusion all around her. The wind was cold and cut into her even though it was at her back, but she loved the wild sound and the salt smell of it and the deepened sense of solitude it brought. She held on to the edges of her winter cloak with gloved hands. Her nose and her cheeks were probably scarlet and shining like beacons.

She had been visiting her friend Tilly Wenzel, whom she had not seen since before Christmas, which she had spent along with January at her brother’s house, her childhood home, twenty miles to the northeast. There had been a new niece to admire, as well as three nephews to fuss over. She had enjoyed those weeks, but she was unaccustomed to noise and bustle and the incessant obligation to be sociable. She was used to living alone, though she had never allowed herself to be a hermit.

Mr. Wenzel, Tilly’s brother, had offered to convey her home, pointing out that the return journey was all uphill, and rather steeply uphill in parts. She had declined, using as an excuse that she really ought to call in upon elderly Mrs. Park, who was confined to her house since she had recently fallen and badly bruised her hip. Making that call, of course, had meant sitting for all of forty minutes, listening to every grisly detail of the mishap. But elderly people were sometimes lonely, Imogen understood, and forty minutes of her time was not any really great sacrifice. And if she had allowed Mr. Wenzel to drive her home, he would have reminisced as he always did about his boyhood days with Dicky, Imogen’s late husband, and then he would have edged his way into the usual awkward gallantries to her.

Imogen stopped to catch her breath when she was above the valley and the cliff path leveled off a bit along the plateau above it. It still sloped gradually upward in the direction of the stone wall that surrounded the park about Hardford Hall on three sides—the cliffs and the sea formed the fourth side. She turned to look downward while the wind whipped at the brim of her bonnet and fairly snatched her breath away. Her fingers tingled inside her gloves. Gray sky stretched overhead, and the gray, foam-flecked sea stretched below. Gray rocky cliffs fell steeply from just beyond the edge of the path. Grayness was everywhere. Even her cloak was gray.

For a moment her mood threatened to follow suit. But she shook her head firmly and continued on her way. She would not give in to depression. It was a battle she often fought, and she had not lost yet.

Besides, there was the annual visit to Penderris Hall, thirty-five miles away on the eastern side of Cornwall, to look forward to next month, really quite soon now. It was owned by George Crabbe, Duke of Stanbrook, a second cousin of her mother’s and one of her dearest friends in this world—one of six such friends. Together, the seven of them formed the self-styled Survivors’ Club. They had once spent three years together at Penderris, all of them suffering the effects of various wounds sustained during the Napoleonic Wars, though not all those wounds had been physical. Her own had not been. Her husband had been killed while in captivity and under torture in Portugal, and she had been there and witnessed his suffering. She had been released from captivity after his death, actually returned to the regiment with full pomp and courtesy by a French colonel under a flag of truce. But she had not been spared.

After the three years at Penderris, they had gone their separate ways, the seven of them, except George, of course, who had already been at home. But they had agreed to gather again each year for three weeks in the early spring. Last year they had gone to Middlebury Park in Gloucestershire, which was Vincent, Viscount Darleigh’s home, because his wife had just delivered their first child and he was unwilling to leave either of them. This year, for the fifth such reunion, they were going back to Penderris. But those weeks, wherever they were spent, were by far Imogen’s favorite of the whole year. She always hated to leave, though she never showed the others quite how much. She loved them totally and unconditionally, those six men. There was no sexual component to her love, attractive as they all were, without exception. She had met them at a time when the idea of such attraction was out of the question. So instead she had grown to adore them. They were her friends, her comrades. Her brothers, her very heart and soul.

She brushed a tear from one cheek with an impatient hand as she walked on. Just a few more weeks to wait . . .

She climbed over the stile that separated the public path from its private continuation within the park. There it forked into two branches, and by sheer habit she took the one to the right, the one that led to her house rather than to the main hall. It was the dower house in the southwest corner of the park, close to the cliffs but in a dip of land and sheltered from the worst of the winds by high, jutting rocks that more than half surrounded it, like a horseshoe. She had asked if she might live there after she came back from those three years at Penderris. She had been fond of Dicky’s father, the Earl of Hardford, indolent though he was, and very fond of Aunt Lavinia, his spinster sister, who had lived at Hardford all her life. But Imogen had been unable to face the prospect of living in the hall with them.

Her father-in-law had not been at all happy with her request. The dower house had been neglected for a long time, he had protested, and was barely habitable. But there was nothing wrong with it as far as Imogen could see that a good scrub and airing would not put right, though even then the roof had not been at its best. It was only after the earl was all out of excuses and gave in to her pleadings that Imogen learned the true reason for his reluctance. The cellar at the dower house had been in regular use as a storage place for smuggled goods. The earl was partial to his French brandy and presumably was kept well supplied at a very low cost, or perhaps no cost at all, by a gang of smugglers grateful to him for allowing their operations in the area.

It had been upsetting to discover that her father-in-law was still involved in that clandestine, sometimes vicious business, just as he had been when

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...