- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

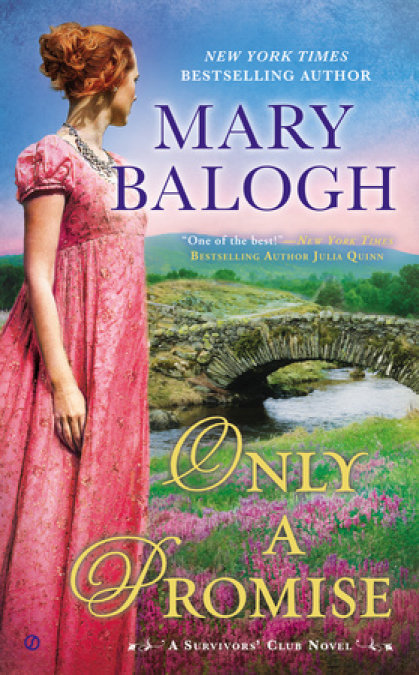

Synopsis

The Survivors’ Club: Six men and one woman, all wounded in the Napoleonic Wars, their friendship forged during their recovery at Penderris Hall in Cornwall. Now, for one of them, striking a most unusual bargain will change his life forever.…

Ralph Stockwood prides himself on being a leader, but when he convinced his friends to fight in the Napoleonic Wars, he never envisioned being the sole survivor. Racked with guilt over their deaths, Ralph must move on...and find a wife so as to secure an heir to his family’s title and fortune.

Since her Seasons in London ended in disaster, Chloe Muirhead is resigned to spinsterhood. Driven by the need to escape her family, she takes refuge at the home of her mother’s godmother, where she meets Ralph. He needs a wife. She wants a husband. So Chloe makes an outrageous suggestion: Strike a bargain and get married. One condition: Ralph has to promise that he will never take her back to London. But circumstances change. And to Ralph, it was only a promise.

Release date: June 9, 2015

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Only a Promise

Mary Balogh

1

There could surely be nothing worse than having been born a woman, Chloe Muirhead thought with unabashed self-pity as she sucked a globule of blood off her left forefinger and looked to see if any more was about to bubble up and threaten to ruin the strip of delicate lace she was sewing back onto one of the Duchess of Worthingham’s best afternoon caps. Unless, perhaps, one had the good fortune to be a duchess. Or else a single lady in possession of forty thousand pounds a year and the freedom to set up one’s own independent establishment.

She, alas, was not a duchess. Or in sole possession of even forty pence a year apart from her allowance from her father. Besides, she did not want to set up somewhere independently. It sounded suspiciously lonely. She could not really claim to be lonely now. The duchess was kind to her. So was the duke in his gruff way. And whenever Her Grace entertained afternoon visitors or went visiting herself, she always invited Chloe to join her.

It was not the duchess’s fault that she was eighty-two years old to Chloe’s twenty-seven. Or that the neighbors with whom she consorted most frequently must all be upward of sixty. In some cases they were very much upward. Mrs. Booth, for example, who always carried a large ear trumpet and let out a loud, querulous “Eh?” every time someone so much as opened her mouth to speak, was ninety-three.

If she had been born male, Chloe thought, rubbing her thumb briskly over her forefinger to make sure the bleeding had stopped and it was safe to pick up her needle again, she might have done all sorts of interesting, adventurous things when she had felt it imperative to leave home. As it was, all she had been able to think of to do was write to the Duchess of Worthingham, who was her mother’s godmother and had been her late grandmother’s dearest friend, and offer her services as a companion. An unpaid companion, she had been careful to explain.

A kind and gracious letter had come back within days, as well as a sealed note for Chloe’s father. The duchess would be delighted to welcome dear Chloe to Manville Court, but as a guest, not as an employee—the not had been capitalized and heavily underlined. And Chloe might stay as long as she wished—forever, if the duchess had her way. She could not think of anything more delightful than to have someone young to brighten her days and make her feel young again. She only hoped Sir Kevin Muirhead could spare his daughter for a prolonged visit. She showed wonderful tact in adding that, of course; as she had in writing separately to him, for Chloe had explained in her own letter just why living at home had become intolerable to her, at least for a while, much as she loved her father and hated to upset him.

So she had come. She would be forever grateful to the duchess, who treated her more like a favored granddaughter than a virtual stranger and basically self-invited guest. But oh, she was lonely too. One could be lonely and unhappy while being grateful at the same time, could one not?

And, ah, yes. She was unhappy too.

Her world had been turned completely upside down twice within the past six years, which ought to have meant, if life proceeded along logical lines, as it most certainly did not, that the second time it was turned right side up again. She had lost everything any young woman could ever ask for the first time—hopes and dreams, the promise of love and marriage and happily-ever-after, the prospect of security and her own place in society. Hope had revived last year, though in a more muted and modest form. But that had been dashed too, and her very identity had hung in the balance. In the four years between the two disasters her mother had died. Was it any wonder she was unhappy?

She gave the delicate needlework her full attention again. If she allowed herself to wallow in self-pity, she would be in danger of becoming one of those habitual moaners and complainers everyone avoided.

It was still only very early in May. A largish mass of clouds covered the sun and did not look as if it planned to move off anytime soon, and a brisk breeze was gusting along the east side of the house, directly across the terrace outside the morning room, where Chloe sat sewing. It had not been a sensible idea to come outside, but it had rained quite unrelentingly for the past three days, and she had been desperate to escape the confines of the house and breathe in some fresh air.

She ought to have brought her shawl out with her, even her cloak and gloves, she thought, though then of course she would not have been able to sew, and she had promised to have the cap ready before the duchess awoke from her afternoon sleep. Dratted cap and dratted lace. But that was quite unfair, for she had volunteered to do it even when the duchess had made a mild protest.

“Are you quite sure it will be no trouble, my dear?” she had asked. “Bunker is perfectly competent with a needle.”

Miss Bunker was her personal maid.

“Of course I am,” Chloe had assured her. “It will be my pleasure.”

The duchess always had that effect upon her. For all the obvious sincerity of her welcome and kindness of her manner, Chloe felt the obligation, if not to earn her living, then at least to make herself useful whenever she was able.

She was shivering by the time she completed her task and cut the thread with fingers that felt stiff from the cold. She held out the cap, draped over her right fist. The stitches were invisible. No one would be able to tell that a repair had been made.

She did not want to go back inside despite the cold. The duchess would probably be up from her sleep and would be in the drawing room bright with happy anticipation of the expected arrival of her grandson. She would be eager to extol his many virtues yet again though he had not been to Manville since Christmas. Chloe was tired of hearing of his virtues. She doubted he had any.

Not that she had ever met him in person to judge for herself, it was true. But she did know him by reputation. He and her brother, Graham, had been at school together. Ralph Stockwood, who had since assumed his father’s courtesy title of Earl of Berwick, had been a charismatic leader there. He had been liked and admired and emulated by almost all the other boys, even though he had also been one of a close-knit group of four handsome, athletic, clever boys. Graham had spoken critically and disapprovingly of Ralph Stockwood, though Chloe had always suspected that he envied that favored inner circle.

After school, the four friends all took up commissions in the same prestigious cavalry regiment and went off to the Peninsula to fight the forces of Napoleon Bonaparte, while Graham went to Oxford to study theology and become a clergyman. He had arrived home from the final term at school upset because Ralph Stockwood had called him a sniveling prig and lily-livered coward. Chloe did not know the context in which the insult had been hurled, but she had not felt kindly disposed toward Graham’s erstwhile schoolmate ever since. And she never had liked the sound of him. She did not like boys, or men, who lorded it arrogantly over others and accepted their homage as a right.

Not many months after they had embarked for the Peninsula, Lieutenant Stockwood’s three friends had been killed in the same battle, and he had been carried off the field and then home to England so severely wounded that he had not been expected to survive.

Chloe had felt sorry for him at the time, but her sympathies had soon been alienated again. Graham, in his capacity as a clergyman, had called upon him in London a day or two after he had been brought home from Portugal. Graham had been admitted to the sickroom, but the wounded man had sworn foully at him and ordered him to get out and never come back.

Chloe did not expect to like the Earl of Berwick, then, even if he was the Duke of Worthingham’s heir and the duchess’s beloved only grandson. She had not forgiven his description of her brother as a lily-livered coward. Graham was a pacifist. That did not make him a coward. Indeed, it took a great deal of courage to stand up for peace against men who were in love with war. And she had not forgiven the earl for cursing Graham after he had been injured without even listening to what Graham had come to say. The fact that he had undoubtedly been in great pain at the time did not excuse such rudeness to an old school friend. She had decided long ago that the earl was brash, arrogant, self-centered, even heartless.

And he was on his way to Manville Court. He was coming at the duchess’s behest, it must be added, not because he had chosen of his own free will to visit the grandparents who doted on him. Chloe suspected that the summons had something to do with the duke’s health, which had been causing Her Grace some concern for the past couple of months. She fancied that he was coughing more than usual and that his habit of covering his heart with one hand when he did so was a bad sign. He did not complain of feeling unwell—not, at least, in Chloe’s hearing—and he saw his physician only when the duchess insisted. Afterward he called the doctor an old quack who knew no better than to prescribe pills and potions that served only to make the duke feel ill.

Chloe did not know what the true state of the duke’s health was, but she did know that he had celebrated his eighty-fifth birthday last autumn, and eighty-five was an awfully advanced age to be.

However it was, the Earl of Berwick had been summoned and he was expected today. Chloe did not want to meet him. She knew she would not like him. More important, perhaps, she admitted reluctantly to herself, she did not want him to meet her, a sort of charity guest of his grandmother’s, an aging, twenty-seven-year-old spinster with a doubtful reputation and no prospects. A pathetic creature, in fact.

But the thought finally triggered laughter—at her own expense. She had whipped herself into a thoroughly cross and disagreeable mood, and it just would not do. She got determinedly to her feet. She must go up to her room without delay and change her dress and make sure her hair was tidy. She might be a poor aging spinster with no prospects, but there was no point in being an abject one who was worthy only of pity or scorn. That would be too excruciatingly humiliating.

She hurried on her way upstairs, shaking herself free of the self-pity in which she had languished for too long. Goodness, if she hated her life so much, then it was high time she did something about it. The only question was what? Was there anything she could do? A woman had so few options. Sometimes, indeed, it seemed she had none at all, especially when she had a past, even if she was in no way to blame for any of it.

* * *

When he found his grandmother’s letter beside his plate at breakfast one morning along with a small pile of invitations, Ralph Stockwood, Earl of Berwick, had only recently returned to London from a three-week stay in the country.

He had come to town because at least it offered the promise of some diversion for body and mind, even if he did not expect to be vastly entertained. He would no doubt lounge about at his usual haunts in his usual aimless way for the duration of the spring Season. The whole of the beau monde had moved here too for the parliamentary session and for the frenzy of social entertainments with which it amused itself with unrelenting vigor for those few months. Ralph did not have a seat in the House of Lords, his title being a mere courtesy one, while procuring a seat in the House of Commons had never held any real appeal for him. But he always came anyway and attended as many parties and balls and concerts and the like as would alleviate the boredom of his evenings. He whiled away his days at White’s Club and frequented Tattersall’s to look over the horses and Jackson’s boxing saloon to exercise his body and Manton’s shooting gallery to maintain the steadiness of eye and hand. He spent as many hours with his tailor and his boot maker and hatmaker as were necessary to keep himself well turned out, though he had never aspired to the dandy set. He did whatever he needed to do to keep himself busy.

And he always yearned for . . .

Well, that was the trouble. He yearned, but could name no object of his yearning. He had a home, Elmwood Manor, in Wiltshire, where he had grown up and that he had inherited with his title from his father. He had also inherited a perfectly competent steward who had been there forever, and therefore he did not need to spend a great deal of time there himself. He had almost sole use of his grandfather’s lavish town house, since his grandparents scarcely came to London any longer and his mother preferred to keep her own establishment. He had fond relatives—paternal grandparents, a maternal grandmother, a mother, three married sisters and their offspring, and some aunts, uncles, and cousins, all on his mother’s side. He had more money than he could decently spend in one lifetime. He had . . . What else did he have?

Well, he had his life. Many did not. Many who would have been his own age, that is, or younger. He was twenty-six and sometimes felt seventy. He enjoyed decent health despite the numerous scars of battle he would carry to the grave, including the one across his face. He had friends. Though that was not strictly accurate. He had numerous friendly acquaintances, but deliberately avoided forming close friendships.

Strangely, he did not usually think of his fellow Survivors as friends. They called themselves the Survivors’ Club, seven of them, six men and one woman. They had all been variously and severely wounded by the Napoleonic Wars, and they had spent a three-year period together at Penderris Hall in Cornwall, country home of George, Duke of Stanbrook, one of their number. George had not been to war himself, but his only son had died in Portugal. The duchess, the boy’s mother, had died a few months later when she threw herself over the high cliffs at the edge of their property. George, as damaged as any of the rest of them, had opened his home as a hospital and then as a convalescent home to a group of officers. And the seven of them had stayed longer than any of the others and had formed a bond that went deeper than family, deeper even than friendship.

It was they, though, his fellow Survivors, who had caused the worse-than-usual restlessness bordering on depression he was feeling this spring. He almost welcomed his grandmother’s letter, then. It suggested, in that way his grandmother had of making an order sound like a request, that he present himself at Manville Court without delay. He had not been there since Christmas, though he wrote dutifully every two weeks, as he did to his other grandmother. His grandfather had not been actively unwell over the holiday, but it had been apparent to Ralph that he had crossed an invisible line between elderliness and frail old age.

He guessed what the summons was all about, of course, even if his grandfather was not actually ill. The duke had no brothers, only one deceased son, and only one live grandson. Short of tracking back a few generations and searching along another, more fruitful branch of the family tree, there was a remarkable dearth of heirs to the dukedom. Ralph was it, in fact. And he had no sons of his own. No daughters either.

And no wife.

His grandmother had no doubt sent for him in order to remind him of that last fact. He could not get sons—not legitimate heirs anyway—if he did not first get a young and fertile wife and then do his duty with her. Her Grace had delivered herself of a speech along those lines over Christmas, and he had promised to begin looking about him for a suitable candidate.

He had not yet got around to keeping that promise. He could use as an excuse, of course, the fact that the Season had only just begun in earnest and that he had had no real opportunity to meet this year’s crop of marriageable young ladies. He had already attended one ball, however, since the hostess was a friend of his mother’s. He had danced with two ladies, one of them married, one not, though the announcement of her betrothal to a gentleman of Ralph’s acquaintance was expected daily. Then, his obligation to his mother fulfilled, he had withdrawn to the card room for the rest of the evening.

The duchess would want to know what progress he was making in his search. She would expect that by now he would at the very least have compiled some sort of list. And making such a list would not be difficult, he had to admit, if he just set his mind to the task, for he was eminently eligible, despite his ruined looks. It was not a thought designed to lift Ralph’s spirits. Duty, however, must be done sooner rather than later, and his grandmother had clearly decided that he needed reminding before the Season advanced any further.

The memory of the precious three weeks he had recently spent with his fellow Survivors at Middlebury Park in Gloucestershire, home of Vincent Hunt, Viscount Darleigh, only added to Ralph’s sense of gloom. All seven of them had been both single and unattached just a little over a year ago during their last annual reunion at Penderris Hall. Without giving the matter any conscious thought, Ralph had assumed they would remain that way forever. As if anything remained the same forever. If he had learned one thing in his twenty-six years, surely it was that everything changed, not always or even usually for the better.

Hugo, Baron Trentham, had been the first to succumb while they were still at Penderris, after he had carried Lady Muir up from the beach, where she had sprained an already lame ankle. They had promptly fallen in love and married a scant few months later. Then Vincent, the youngest of their number, the blind one, had fled one bride chosen by his family and then had narrowly missed being snared by another. He had been prompted by gallantry to offer for the girl who had come to his rescue that second time when she had thwarted the schemer, but ended up being chucked out of her home as a result. They had married a few days after Hugo and in the same church in London. Meanwhile Ben—Sir Benedict Harper—had been staying with his sister in the north of England when he met a widow who was being treated shabbily by her in-laws. He had chivalrously accompanied her when she fled to Wales and had ended up marrying her as well as running her grandfather’s Welsh coal mines and ironworks. Bizarre, that! And now this year, during their reunion in Gloucestershire, Flavian, Viscount Ponsonby, had suddenly and unexpectedly married the widowed sister of the village music teacher and borne her off to London to meet his family.

Four of them married in little more than a year.

Ralph did not resent any of the marriages. He liked all four of the wives and thought it probable that each marriage would turn out well. Although in truth, he knew he must reserve judgment upon Flavian’s, since it had happened so recently and so abruptly, and Flave was a bit unstable at the best of times, having suffered head injuries and memory loss during battle.

What Ralph did resent was change—a foolish resentment, but one he could not seem to help. He certainly did not resent his friends’ happiness. Quite the contrary. What he did resent, perhaps—though resentment might be the wrong word—was that he had been left behind. Not that he wanted to be married. And not that he believed in happiness, marital or otherwise. Not for himself, anyway. But he had been left behind. Four of the others had found their way forward. Soon he would be married too—there was going to be no escaping that fate. It was his duty to marry and produce heirs. But he could not expect the happiness or even the contentment his friends had found.

He was incapable of love—of feeling it or giving it or wanting it.

Whenever he said as much to the Survivors, one or another of them would remind him quite emphatically that he loved them, and it was true, much as he shied away from using that exact word. He loved his family too. But the word love had so many meanings that it was in fact virtually meaningless. He had deep attachments to certain people, but he knew he was incapable of love, that something special that held together a good marriage and sometimes even made it a happy one.

There were a few social commitments he was forced to break after his grandmother’s letter arrived, though none that caused him any deep regret. He sent his apologies to the relevant people, wrote a brief letter to his mother, who was in town and might expect him to call, and set out for Sussex and Manville Court in his curricle despite the fact that it was a brisk day in early May and there was even the threat of rain. He never traveled by closed carriage when he could help it. His baggage followed in a coach with his valet, though he doubted he would have much need of either. His grandmother would be too eager to say her piece and quickly send him back to London with all its parties and balls and eligible brides.

Unless Grandpapa really was ill, that was.

Ralph felt an uncomfortable lurching of the stomach at the thought. The duke was a very old man, and everyone must die at some time, but he could not face the prospect of losing his grandfather. Not yet. He did not want to be the head of his family, with no one above him and no one below. There was a horrible premonition of loneliness in the thought.

As if life was not an inherently lonely business.

He arrived in the middle of the afternoon, having stopped only once to change horses and partake of refreshments, and having been fortunate enough not to get held up at any toll booths or to get behind any slow-moving vehicles on narrow stretches of road. The front doors of Manville stood open despite the fact that the afternoon was not much warmer than the morning had been. Obviously he was expected, and there was Weller, his grandfather’s elderly butler, standing in the doorway and bowing from the waist when Ralph glanced up at him. He was not looking particularly anxious—not that Weller ever displayed extreme emotions. But surely he would have done if Grandpapa were at his last gasp.

And then his grandfather himself appeared behind Weller’s shoulder and the butler stepped smartly aside.

“Harrumph,” the duke said—a characteristic sound that fell somewhere between a word and throat clearing—as Ralph relinquished the ribbons to a groom and took the steps up to the doors two at a time. “Making a filial visit just as the London Season is swinging into action, are you, Berwick? Because you could not go another day without a sight of Her Grace’s face, I daresay?”

“Good to see you, sir.” Ralph grinned at him and took the duke’s bony, arthritic hand in his own. “How are you?”

“I suppose Her Grace wrote to tell you I was at death’s door,” the old man said. “I daresay I am, but I have not knocked upon it or set a toe over the doorsill yet, Berwick. Just a bit of a cough and a bit of gout, both the results of good living. Well, if you were sent for, you will be expected upstairs. We had better not keep the duchess waiting.”

He led the way up to the drawing room. The butler was already stationed outside the double doors when they got there, and he flung them open so that the two men could enter together.

The duchess, who looked more like a little bird—a fierce little bird—every time Ralph saw her, was seated beside the fire. She nodded graciously as Ralph strode across the room to bend over her and kiss her offered cheek.

“Grandmama,” he said. “I trust you are well?”

She glanced at the duke. “This is a pleasant surprise, Ralph,” she said.

“Quite so,” he agreed. “I thought I would run down for a day or two to see how you did. And Grandpapa too, of course.”

“I must have the tea tray brought up,” she said, looking vaguely about her as though expecting it to materialize from thin air.

“Allow me to ring the bell, Your Grace,” a lady who was sitting farther back from the fire said, getting to her feet and moving toward the bell rope.

“Oh, thank you, my dear,” the duchess said. “You are always most thoughtful. This is my grandson, the Earl of Berwick. Miss Muirhead, Ralph. She is staying with me for a while, and very thankful I am for her company.”

It was said graciously, and for one startled moment Ralph thought that perhaps he had been brought here to consider the guest as his prospective bride. But he could see that she was no young girl. She might even be older than he. She was not dressed in the first stare of fashion either. She was tall and on the slender side with a pale complexion and what looked like a dusting of freckles across her nose. She might have looked like a faded thing, or at least a fading thing, if it had not been for her hair, which was thick and plentiful and as bright a red as Ralph had ever seen on a human head.

“My lord.” She curtsied without either looking at him or smiling, and he bowed and murmured her name.

His grandmother did not actually ignore her. Neither did she draw her any more to Ralph’s attention, however, and he relaxed. Obviously she was of no particular account. Some sort of companion, he supposed, an aging, impecunious spinster upon whom Her Grace had taken pity.

“Now, tell me, Ralph,” his grandmother said, patting the seat of the chair beside her, “who is in town this year for the Season? And who is new?”

Ralph sat and prepared to be interrogated.

2

The Earl of Berwick was really quite different from what Chloe had expected.

There were his looks, for one thing. He was not the handsome boy she had always imagined, frozen in time, arrogant and magnetically attractive, riding roughshod over the feelings of others. Well, of course he was no longer that boy. It had been eight years since he and Graham left school, and during those years he had been to war, lost his three friends, been desperately wounded himself, and made a slow recovery—perhaps. Perhaps he had recovered, that was. She had never really wondered what war did to a man apart from killing him or wounding him or allowing him to return home when it was over, mercifully unscathed. She had considered only the physical effects, in fact.

Lord Berwick fell into the second category—wounded and recovered. That should have been the end of it. He had been left with scars, however. One of them was horribly visible on his face, a nasty cut that slashed from his left temple, past the outer corner of his eye, across his cheek and the corner of his mouth to his jaw, and pulled both eye and mouth slightly out of shape. It must have been a very deep cut. Bone deep. The old scar was slightly ridged and dark in color and made Chloe wince at the thought of what his face must have looked like when it was first incurred. That it had missed taking out his eye was nothing short of a miracle. There must have been some permanent nerve damage, though. That side of his face was not as mobile as the other when he talked.

And if there was that one visible scar, there were surely others hidden beneath his clothes.

It was not just his scarred face, though, and the possibly scarred body that made him very different from the person she had expected and made her wonder more than she had before about what war did to a man. There were his eyes and his whole demeanor. There was something about his eyes, attractively blue though they were in a face that was somehow handsome despite the scar. Something . . . dead. Oh, no, not quite that. She could not explain to herself quite what she saw in their depths, unless it was that she saw no depths. They were chilly, empty eyes. And his manner, though perfectly correct and courteous, even affectionate toward his grandparents, seemed somehow . . . detached. As though his words and his behavior were a veneer behind which lived a man who was not feeling anything at all.

Chloe had gained this chilly impression of her brother’s former schoolmate at their first meeting and realized how foolish she had been to expect him to be exactly as Graham had described him all those years ago. He was not that boy any longer, and had probably never been exactly as she had imagined him anyway. She had only ever seen him, after all, through the biased eyes of her brother, who was very different from him and had always both envied and resented him.

Chloe found this man, this stranger, disturbing, a cold, brooding, detached, controlled man it would surely be impossible to know. And a man who seemed largely unaware of her existence despite the fact tha

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...