- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

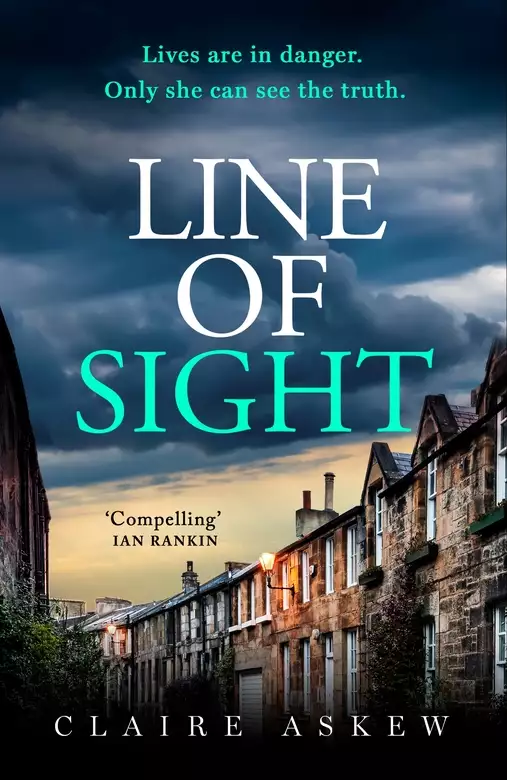

Synopsis

A woman slipping through the cracks . . .

When a young Vietnamese girl goes missing in Scotland, DI Birch knows there is more to the case than meets the eye. Her colleagues won't take it seriously - but Helen's instinct tells her that Linh is in mortal danger.

A psychic determined to help . . .

Beatrice knows something terrible has happened to three young people in Edinburgh. She can see them in her mind's eye - frightened and alone, desperate for help. Ever since she was a child, she's had visions of the future - and she's ignored them before, with dangerous consequences. This time, she must help the police find Linh.

A showdown where not everyone will survive . . .

When a second woman goes missing, DI Birch is forced to pay attention to what Beatrice is saying. But will the police listen to the truth in time? Or is it already too late?

Release date: February 6, 2025

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Line of Sight

Claire Askew

Bee, 2010

The first time it happened, I thought it was just a dream. A weird dream like any other, though it shook me awake at 3.32am, my heart spluttering. I know it was 3.32am because I sat up in bed, put on the light, and recorded it in my dream journal: Thursday 20 May 2010, 3.32am. I wrote:

It was night, and I was standing in someone’s back garden. Not somewhere I’d been before, not familiar. The house was a little white bungalow, and the garden was a long, narrow lawn with huge trees at the bottom. Leylandii that had grown out of control. I stood in the deep shadow of those trees, looking at the house. There was a main road beyond it, and I saw a lit-up N49 bus go by, empty. I walked up the garden to the back door of the bungalow, and let myself in. It was dark inside, but the moon shone into the window, and I could see in the gloom that this was the kitchen. It was very old-fashioned, 1960s style: chipped Formica units with rail handles; a black-and-white linoleum floor, like in the old Flash ads. I had a horrible feeling, standing there: this house was a bad place, something bad was happening in it. I wanted to leave, but instead I walked through the kitchen and into the utility room, tacked on to one side.

I knew things about this house, as though I’d lived there. I knew that there was a loose edge to the linoleum – that same black-and-white linoleum – just under the lip of the washing machine. I knew that if you lifted that flap, it would pull back a whole section, revealing the bare boards underneath. I knew that once I did that, I’d reveal a trapdoor set into the floor. I knew that if I looked in one of the cupboards, I’d find a short pole I could use to lever the trapdoor open. I knew that it had been designed this way, so that when it was closed and the lino laid over it, the floor was completely flush: no sign at all that anything was under there. That this house had a secret room, and the secret room was where the bad feeling lived.

I did it: I levered the trapdoor open, and though I didn’t want to, stepped down into the hole. There were wooden stairs that creaked loudly, and I felt afraid that I’d wake whoever lived in this house, and they’d come and shut me up in this secret place. There was no moonlight now: just a pitch-black space that felt close, and smelled like concrete dust and human sweat. When my feet met the floor, I could feel through the soles of my shoes that it was bare earth, and cold. And then I realised there was something down there with me – some sort of animal. I couldn’t see it, but I could hear it breathing. Then, as if it sensed I was there, it started to cry out – these horrible, anguished cries, almost like a human baby. I turned to get back to the stairs, to get out, but I couldn’t find them in the dark. Above my head, the trapdoor slammed shut. I woke up, panicked and thrashing.

Just a dream, I told myself, and gradually forgot the shabby kitchen, the secret room, the high, thin cries in the darkness. Just a dream, until the Edinburgh Evening News report, two months later. Missing toddler Rosie Cole found alive and well in Mountcastle neighbour’s cellar. The same horrible feeling from the dream returned as I pinned the paper to the kitchen table with my forearms, put my face close, and read. The missing three-year-old had been hidden in a makeshift room in the basement of a house just a few doors down from her own. The house was a white 1960s bungalow in the suburb of Mountcastle; the paper had printed a photo of it, police tape billowing from the front garden fence. The skyline above the bungalow’s roof was ragged with unchecked leylandii. Mountcastle: I googled it. The 49 was the only bus that passed directly through. A fifty-five-year-old man, the paper said, had been arrested in connection with Rosie’s disappearance. She’d been missing since Wednesday 19 May.

The article kept the details scant, but I knew. The walls of the cellar were concrete, but the floor was earth. She’d been cold. There was no window, and no light, save whatever light the man brought down – a torch, perhaps, or a lantern. From where she lay on that dirt floor, Rosie could hear him moving around, the joists above her head shifting as he walked. The scrape of the lever in the trapdoor. The creak of the stairs. She was hungry, and hurt, and the man was strange and frightening. She cried at first, but then she stopped crying, because no one ever came.

Alive and well, the article said, and every time I thought of that phrase, my teeth set on edge. I’d dreamed of Rosie on her first night in that place, before there was even a formal missing persons report. She’d been held there a further two months. I didn’t want to think of how she’d suffered, but I knew: the horrible feeling ached in my bones like flu. If I’d only told someone. But who? The police? Who’d have believed me? It was a dream, they’d have said. It was only a dream.

Birch, Monday 10 January

‘How’s the physio going?’

DI Helen Birch had been attending counselling for almost six months now, and she’d never known her therapist, Dr Jane Ryan, to be anything other than perfect. She kept her hair cropped short, but it never seemed to need a trim. She never lost her notes or misremembered anything – she always seemed to be a step ahead of Birch at every turn. And yet, Dr Jane hadn’t taken her Christmas cards down yet. Birch was finding it extremely distracting.

‘I’m sorry?’

Dr Jane repeated herself. ‘How’s the physio going? You’ve walked in here with just a stick. When I saw you before the holidays, you were still on the crutches. Looks like you’re making great progress.’

Birch touched the curved handle of the cane she’d leaned against her chair, as though checking it hadn’t somehow disappeared. ‘I should probably ’fess up to the fact that I did that myself,’ she said. ‘I haven’t been back to physio since before Christmas. That last time, we talked about how I was getting to the point where I could switch to just a stick, and honestly, I was so ready to be finished with those damn crutches. So, one day over the holiday, I just did it.’ She touched the walking stick again, hearing her own voice softening. ‘This was my mum’s – she needed it, towards the end of her life. I don’t know why I kept it. Maybe because it was something I knew she’d touched, interacted with a lot, before she died. Anyway, I’m glad I have it now. Though it’s not exactly trendy.’

Dr Jane smiled. ‘As long as it’s doing its job,’ she said, ‘that’s the main thing. Your pain’s okay?’

Birch shrugged. ‘As okay as it ever is. I’m still managing it fine.’

‘And the nightmares?’

Birch flinched at this, and realised Dr Jane had noticed. She wished she’d never said anything about the nightmares.

‘There’s a part of me,’ she said, ‘that wishes I’d never said anything about the nightmares.’ It had taken her six months, but she’d come to learn that, as a general rule, it was a good idea to just say the thing she was thinking. Dr Jane usually knew, whether she said it or not, so she may as well say it.

‘Why’s that?’

Birch couldn’t stop looking at the Christmas cards. Were they from clients? She hadn’t sent one to Dr Jane. She wasn’t sure if it was appropriate or not.

‘I don’t know. Because it’s to be expected, isn’t it? I was shot, that’s a traumatic event. Aren’t the nightmares just my subconscious working through it? I’ve been thinking, maybe they’re good for me. Maybe I need to have them. Maybe they’re actually a sign that I’m dealing with it.’

Dr Jane cocked her head. ‘Dreams can certainly serve a purpose,’ she said. ‘But when you first mentioned the nightmares to me, you suggested that they were becoming quite life-limiting. They were affecting your sleep, and, by extension, your concentration. Obviously, it’s completely up to you what we talk about here – but I definitely think there’s value in discussing anything that’s limiting your life. Seeing if we can’t get a bit of a better handle on that.’

Birch stepped out into the street, dazzled by the bright, crisp day. She always felt a little unusual after a therapy session: generally, she needed at least half an hour for her brain to stop whirring and return to its normal programming. She was enjoying being off the crutches, but also missed them, and she thought about the times she’d heard amputees talk about missing their absent limbs. The crutches’ presence had become so familiar to her that now – still walking at a hobble, but far less encumbered than she had been – she felt oddly light without them. The pain in her hip – where the shotgun blast had shattered the bone – was a low, constant hum, but the hum was that little bit quieter with every day that passed. Soon, Birch hoped, she’d be able to drive her car again. Of all the things she’d missed in the months since the shooting, it was driving alone – with something good on the radio and the windows down – that she yearned for the most.

‘You mentioned,’ Dr Jane had said, ‘that some of the nightmares were recurring.’

‘A few of them, yes. One, in particular.’

‘Would you feel okay telling me about it? About that one dream in particular?’

Birch had taken a deep breath to indicate that yes, she’d be fine to tell the story, but then she’d paused, unsure how to begin.

‘You don’t have to give any specific details,’ Dr Jane urged. ‘Just tell me what feels most pressing.’

Birch nodded. ‘It’s a dream about work,’ she said. ‘That’s how it starts. I’m at work, sitting at my desk. Everything seems to be normal, mundane. But then something changes.’

‘Something literally changes? Or it’s more of a feeling?’

‘It’s a feeling,’ Birch replied. ‘Suddenly I feel a real sense of … threat? But perhaps threat isn’t the right word. Foreboding, maybe. Like, nothing’s wrong in the moment, but I know that something bad is about to happen, and I know there’s nothing I can do about it. Then the room begins to fill with water.’

Dr Jane blinked. Whatever she’d been expecting, it wasn’t that. ‘There’s a flood?’

Birch cocked her head to one side. ‘Sometimes,’ she said. ‘But it depends. Some nights, I dream that I notice a wet patch on the office floor, and it spreads and gets bigger and bigger, until the whole room starts to flood. Or I look up and see there’s a drip coming from the ceiling, and what starts as a trickle turns into a gush, and then a torrent.’

‘But other times it’s not like that?’

‘No.’ Birch was beginning to feel boring – the way you do when you get so far into describing a dream you’ve had, and you realise that the details that feel fascinating to you are not, in fact, interesting to whoever’s listening to you. But Dr Jane was asking, so she had to go on. ‘Sometimes, it’s like that scene in The Shining. You know, where the lift opens, and all the blood spills out? Sometimes the water is like that. It comes crashing in through the office door, and there’s no way out.’

‘That sounds pretty frightening.’

Birch nodded. ‘The frightening thing about it,’ she said, ‘is the not being able to get out part. When the flood begins gradually, I cross the room and try to open the office door, but it’s locked. I can see my colleagues outside in the bullpen, going about their business as if nothing’s happening. The water gets up to my knees, and I can see it’s up to their knees as well – they’re being flooded out, too – but it’s like they haven’t noticed. And I shout at them and bang on the door, and no one hears me. No one comes to let me out.’

‘You feel powerless.’

‘Yes.’

‘What about the times when the water comes suddenly, from outside the room? Where are your colleagues then?’

Birch looked down at the floor. She felt almost embarrassed about the way her subconscious was behaving. ‘I know this is exceptionally weird,’ she said, ‘but in that version of the dream, I somehow know that they’re all dead. They’ve all already drowned.’

Dr Jane nodded, but didn’t speak. After a moment’s silence, she looked down at the screen of her iPad, and tapped in a note.

‘How’s that,’ Birch had said then, trying to laugh, ‘for a conversation stopper?’

Birch walked slowly through the streets of Stockbridge, taking her time. She had a little buzz on, as if she’d drunk a strong beer on an empty stomach. She’d come to like therapy, but still found it uncanny: sometimes, after a session, she was left feeling as though Dr Jane had in fact opened her skull and literally poked around in her thoughts. She stopped in front of the Bethany Christian Trust shop, and peered into the window. They always had a selection of interesting things to look at: today there was an old printer’s tray full of wooden letters neatly arranged in their slots, along with an ugly silver lustre teapot that reminded Birch of going to her granny’s house when she was wee. There was also a plastic storage box full of mismatched Christmas baubles, a sheet of foolscap stuck to the front of it on which hand-drawn bubble writing read ‘January Sale Bargain Box!!! 10 for £1!!!!’ The charity shop called to her – she wanted to go in and loiter among the 50p paperbacks and baskets of scarves.

‘I never go in those shops,’ she heard a familiar voice say, as clear in her head as if her dead mother were standing right beside her. ‘They’re full of clothes other people have died in.’

Birch grinned. After a final brief glance at the lustre teapot – so shiny that her own face grimaced back at her from its convex surface – she wandered on.

‘Do you think it means,’ she’d asked Dr Jane, ‘that I want all my colleagues dead? Do you think I ought to be on some sort of list?’

She was joking, but could hear the subtle trill of anxiety somewhere in her own voice. She’d never had a dream recur this persistently before. It was disturbing to be sent the same cryptic message night after night, but not be able to understand the code. It felt a little like the time that Charlie had reappeared: her missing brother’s return was foretold by a series of crank phone calls, which came at fifteen-minute intervals throughout the day. Someone trying to tell her something, and Birch clueless as to what it might be.

Dr Jane had laughed at the joke, thankfully.

‘Do you think it’s that? You know that if you’re having homicidal thoughts, I’m obliged to report it.’

They’d laughed together. Birch liked it when she could make Dr Jane laugh, though she’d never have said that out loud to anyone.

‘No,’ she said. ‘I don’t wish my colleagues dead. Apart from anything else, when I’m in the dream, that’s part of the horror. I’m not happy about them being washed away by the flood, I’m terrified.’

Dr Jane let the laughter fade, and they sat in silence again.

‘In the slow version of the dream,’ she said, eventually, ‘what happens when the water gets over your head?’

Birch hung a right on to Raeburn Place, one of her favourite streets in Edinburgh. Her colleague, DS Amy Kato, lived here, in a tiny, immaculate flat. The street was full of coffee roasters, wine bars and artisan cheese shops. Because the hip young things who lived here valued authenticity, there was also an old-fashioned greengrocer’s, an old-fashioned hardware store, a florist with a beautiful window display, and a post office with cheery staff who knew everyone. The place was full of happy dogs in little tartan coats. Walking through Stockbridge was like walking through one of the Shirley Hughes storybooks of Birch’s childhood.

She stopped outside the narrow Mexican gift shop with its hammered tin hearts and strings of tiny ceramic chilli peppers. It was cold out, so the door was closed, but Birch could still smell the incense burning inside. On the window, someone had drawn the words ‘Human Kind: Be Both’ in looping coloured chalk pen. Inside, the shop glittered like a jewellery box, and Birch had to peel herself away and carry on along the frigid pavement.

‘I wake up,’ she’d said, ‘and then that’s it, I’m awake. Sometimes it’s 2am, sometimes it’s 5am, but every time, I wake up with my heart hammering like I’ve run up ten flights of stairs. There’s no getting back to sleep after that.’

Dr Jane had entered another note on the iPad. The room was quiet enough that Birch could hear the soft patter of the therapist’s fingertips against the glass.

‘And you’ve had this dream … how many times, would you say?’

‘In one form or another? I’d say dozens. Enough times that I’ve stopped counting.’

Dr Jane hadn’t looked up from the screen. ‘And you think it’s as a result of the shooting, that you’re having these nightmares?’

‘Yes.’

Dr Jane met Birch’s eye, and held her gaze. ‘Even though the content of the dream has nothing to do with Operation Kendall, or what happened?’

Birch had been working on this for six months: working to be okay with the sustained eye contact that seemed to be part of Dr Jane’s therapeutic style. She’d learned somewhere – in some dim and distant past piece of training – that people’s eyes automatically move to the left if they’re remembering something, but to the right if they’re making something up. Over the course of these months, she’d noticed with horror that it was true: whenever she tried to fib or fudge an answer, her eyes moved rightwards, towards the door in the corner of the room, the exit she could lunge for if things got too uncomfortable. She’d realised she was looking at it in that moment, and flicked her eyes away – too late. Dr Jane must surely have seen.

‘I don’t know,’ Birch had lied, ‘what other explanation there could be.’

The shops had petered out now, and with nothing much else interesting to look at, Birch focused on her steps, maintaining the studied walk that caused the least amount of pain in her hip. She stopped at the junction where East Fettes Avenue became Comely Bank Avenue, and stared up the hill at the neatly stacked tenements, their identical bay windows and black iron railings. She couldn’t deny it any longer: it was time to go to work. Her Fettes Avenue office was only five minutes away. These were the last few days of her phased return: next week, the compressed days would become full days, no doubt with overtime piling up from the off, diligently entered in the spreadsheet, never to be claimed back.

‘Promise me,’ Anjan had said, sitting her down a few weeks before Christmas, the morning of her first phased-return half-day, ‘you won’t overdo it. Promise me things won’t go back to the way they were before.’

Birch had scoffed at him, as he must have known she would: Anjan Chaudhry was renowned for being first into the office and last out of the courtroom, for poring over casefiles on the weekends and pulling all-nighters before a major judgement.

‘In my line of work,’ he’d say, ‘it’s expected. It starts in law school and it never, ever stops.’

You think my line of work is any different? She’d said it plenty of times in the past, but didn’t see the point, just lately. It was a fight they’d had enough times to know that neither one could win, so they’d stopped trying. Anjan could no longer understand her loyalty to the job. That job, he’d say, had landed her in hospital with a gunshot wound. The job that had seen her, while still in recovery, left to fight off a violent criminal without back-up, setting her physio treatment back to zero. How could she be loyal to DCI McLeod, who had caused every part of her present predicament? Anjan repeatedly demanded an answer. Birch couldn’t admit to him, or anyone – not even Dr Jane – that lately, she was struggling to understand it, too.

‘It won’t,’ she’d said, that morning, enjoying the gentle weight of Anjan’s hands on her shoulders, as though he were trying to stop her from floating away. ‘I promise.’

Her eyes had shifted rightwards then, too.

Bee, 1977

I didn’t know the old man wasn’t real. I heard other children talk about their grandfathers – indeed, sometimes their grandfathers turned up to collect them at the school gates – so I assumed that he was mine. He looked like those other men: his head was bald, and there were lines around his eyes that made his face seem kind. He looked, I thought, like a tortoise. His clothes were strange, but I’d been taught not to stare or make comments about people who were different.

We lived in what would once have been a fancy Edinburgh residence, though it was shabby by the time we owned it, and only became shabbier as a result of us moving in. It was a detached townhouse: I slept in what my mother called the servants’ quarters: a wee narrow room with a sink, up its own twisty staircase under the roof. Rain trickled in under the slates and made large brown blooms on the ceiling. In really bad weather, the blooms let down their own little raindrops: I thought they were indoor clouds, because the plaster swelled and puffed them out like the fluffy clouds of cartoons. My mother showed me how to put down pans to catch the drips, and I’d lie awake listening to the weird, flat xylophone music they made.

My father was meant to fix the house. He seemed to make a lot of noise – hammering, drilling, swearing at things – but nothing ever really improved. A section of the living room ceiling was held up by scaffolding poles, following the ill-advised demolition of an internal wall. My mother gave me sock yarn, which I strung between the struts, and turned into a washing line for my dolls’ clothes. At Christmas, we looped tinsel around those poles. No one ever came to visit that house.

Late one afternoon, at the tea table, I asked, ‘Where does my grandpa sleep?’

My mother looked at my father, who would have been behind an evening newspaper, though I don’t remember clearly. I wasn’t looking at him.

‘Your grandpa?’ my mother asked.

‘Yes. Where does he sleep?’

My father still didn’t speak.

My mother leaned over the table towards me. ‘Sweetheart,’ she said, ‘why are you asking that?’

I wasn’t accustomed to my questions being answered with other questions. Often, when I asked things, I’d be told, ‘Because,’ or, ‘You’ll understand when you’re older.’ I’d begun to learn that when my father said, ‘I don’t know, ask your mother,’ it wasn’t because he didn’t actually know. Nevertheless, I considered my mother the fount of all knowledge, and couldn’t understand her evasiveness.

‘He says goodnight to me every night,’ I replied, ‘after I’ve gone to bed. Where does he go, after that? Does he have his own house?’

My mother’s eyelashes were fluttering. ‘Your daddy says goodnight to you every night,’ she said. ‘Are you asking where Daddy sleeps?’

I remember putting my hand firmly on the table then, because it made my mother jump. I’d never managed to do that before. I recall that I felt quite grown-up.

‘No,’ I said, as though speaking to an idiot. ‘I mean my grandpa. He’s different from Daddy. I know he’s different from Daddy.’

At this point, my father must have emerged from behind his newspaper, because he said, very clearly, and without emotion, ‘Kid, both your grandpas are dead.’

There was a pause, during which I probably looked to my mother for confirmation. I was old enough to understand the word dead, in the sense that I knew it meant that someone had gone away, permanently.

‘Long dead,’ my father added. ‘And good riddance to the pair of them.’

I imagine my mother must have given him a look.

‘So … if he’s not my grandpa, then who is he?’

I wonder if this panicked my mother. I wasn’t worried, myself: I was still young enough to believe that grown-ups had logical explanations for absolutely everything, even if they sometimes kept those explanations to themselves.

‘Who, darling?’

I didn’t know why she was acting this way.

‘The old man,’ I said. ‘The one who comes to say goodnight to me every night.’

My father must have thrown his paper down on the table, because I remember the rattle of cutlery, of cups jumping in their saucers.

‘What?’

I remember my eyes boggling at the pair of them – did they really not know about the old man?

‘There’s an old man,’ I said. I spoke slowly. For the first time, I thought perhaps my parents were not as smart and sensible as I had always assumed. ‘He comes to my room every night, after I’ve had my bath and Mummy has tucked me in and Daddy has said goodnight. He comes to say goodnight, too.’

‘Beatrice,’ my mother said, and for the first time since the conversation began, I felt a spike of worry. My parents only ever called me by my full name when I was in trouble. ‘You’re telling me an old man – a stranger – comes into this house at night? How does he get in?’

‘Through the door.’

My father was shaking his head. I could hear his breath moving faster, which meant he was getting angry. I was in trouble.

‘Impossible,’ he said. ‘That’s impossible. Sheila, you surely can’t believe this? This house creaks like a bloody sinking ship. There’s no way someone could get up those stairs without us hearing them.’

This quietened me. I’d never noticed it before, but now my father mentioned it, I realised that no, oddly, the old man never made any noise – yet the floor of my room was an assault course of squeaks and cracks. I never dared put even a toe on those floorboards after bedtime, because I knew my parents would realise I was still awake.

My father rounded on me.

‘She’s making it up, the wee devil. She’s lying.’

I was old enough to know that lying was very wrong, and punishable – in school, at least – by a ruler to the knuckles.

‘I’m not, Daddy,’ I said. ‘I promise, I’m not lying.’

I was getting worried now. I didn’t want the ruler on my knuckles, nor did I want any other form of punishment. I hadn’t expected the conversation to turn this way, and I felt bewildered. But I still wasn’t as worried as my mother appeared to be.

‘What does this old man look like?’ she asked.

‘Sheila,’ my father said, ‘you must be joking.’

I decided to take a risk, ignore him, and answer my mother. ‘He’s old,’ I said. ‘He doesn’t have very much hair, and his head is shiny. He has wrinkly eyes, and he wears a black suit, like the one Daddy has. Except his has a flappy part that covers his …’ Here I paused, and lowered my voice, realising I was going to have to say – at the tea table, no less – a word I knew to be taboo. ‘His bottom,’ I whispered. Again, I couldn’t help but feel rather grown-up.

I remember my father’s face was quite red. I’m still not sure if he was angry with me for spinning a yarn – as he saw it – or angry with my mother for listening to it.

‘Does he talk to you, this man?’ she asked.

I shrugged. ‘Not really, Mama. He just strokes my hair and says, “Goodnight, little one,” and then he goes away.’

At the other end of the table, my father was making hissing, fizzing noises, like a punctured tyre held under water.

‘Is there anything else about him?’ my mother asked.

‘Yes,’ I replied. ‘He wears white gloves on his hands.’

I helped to tidy the tea things away, and then I was sent to my room. I lingered on the stairs, hearing my parents talk in fierce whispers. At dinnertime, I was called back downstairs, and my father gave me a rather stiff dressing-down for telling fibs, and scaring my mother. She stood behind him, not looking at me. My punishment was going to bed early without pudding, and that night, the old man didn’t come.

Years later, I would often walk past that house. I’d remember the scaffolding poles in the living room, the dens I built in the twisty rhododendrons in the garden. I’d remember my baby brother being born, and my mother putting her foot down about living in a building site. I’d remember us leaving soon after, Tommy still a babe in arms. But more than anything else, I’d remember the kind old man who wasn’t real.

Except he was real, I was certain of it. I’d heard his voice, and felt the warm weight of his hand on my head. After I told my parents about him, he’d stopped visiting me every night – but he still turned up occasionally, when I most needed him. If there was a thunderstorm and I was afraid, or if I was hot and sick and miserable in bed, then he’d be there, with his comforting, white-gloved hands. One of the first things I ever looked up online – as soon as I got the new-fangled internet – was the history of that house. I discovered it originally belonged to an eminent, wealthy man: a Colquhoun or a Farquharson, one of those types. It was his pied-à-terre, a place in town away from his sprawling rural estate. The man was a bachelor, and most of the year the house was kept up by servants, only one of whom lived in. A butler, whose former room I guessed I must have slept in every night. The census listed one name only – Fraser – but whether this was his first or last name, I couldn’t be sure. A butler, who for formal occasions must have dressed in a smart black tailcoat, and white gloves. I was seven when we left that house. Fraser was my first ghost.

Birch, Monday 10 January

The problem with the phased

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...