- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

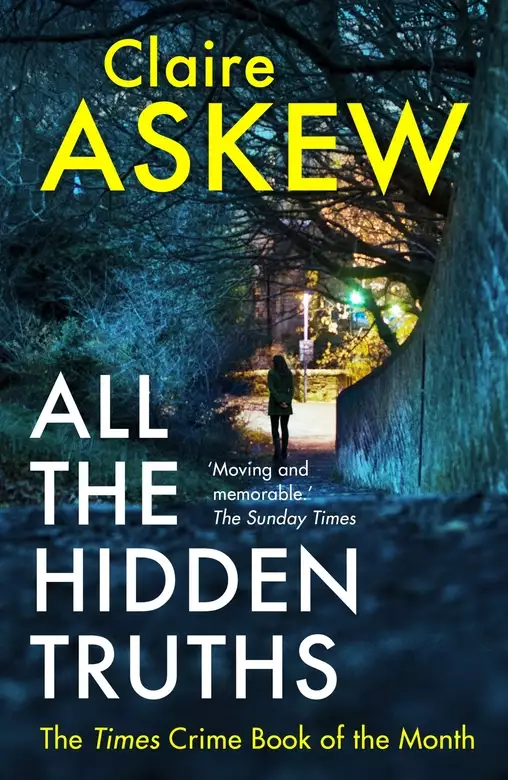

A wrenching, gripping, unforgettable debut crime novel for fans of Susie Steiner and Kate Atkinson.

This is a fact: Ryan Summers walked into Three Rivers College and killed 13 women, then himself.

But no one can say why.

The question is one that cries out to be answered—by Ryan's mother, Moira; by Ishbel, the mother of Abigail, the first victim; and by DI Helen Birch, put in charge of the case on her first day at her new job. But as the tabloids and the media swarm, as the families' secrets come out, as the world searches for someone to blame...the truth seems to vanish.

A stunningly moving novel from an exciting new voice in crime, All Hidden Truths will cause you to question your assumptions about the people you love and reconsider how the world reacts to tragedy.

Release date: August 9, 2018

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

All the Hidden Truths

Claire Askew

Moira Summers was on the top deck of the number 23 bus, her face turned up to the sun like a cat – it was the first day that year that could really have been called hot. She felt the bus pitch and begin to chug up the Mound. She’d always loved this view from the 23: on the right, the Castle, black and hewn, seeming to rise up out of Princes Street Gardens’ seething trees. On the left, the whole of the New Town laid out in its smart grid. In the sunshine, Jenners department store and the Balmoral Hotel looked like gilded chocolate boxes, and the Scott Monument was Meccano-model-like, unreal.

She forced herself to press the bell and shuffle out of her seat, down the aisle and then the stairs of the swaying bus. She alighted outside the National Library of Scotland, whose double doors were mobbed by a gang of school kids. Moira felt herself tense. She’d come to sit in peace and do some studying for her OU degree, but the thought of being holed up in the dark, oppressive reading room on a day like this had already put a sullen feeling in her chest. A school-trip group clattering about the place practically guaranteed that she’d get nothing done.

‘I want you in pairs!’ A young, blonde woman was standing at the top of the steps inside the library entrance. ‘In pairs, in pairs,’ she chimed at the teens, but they paid no attention. Moira guessed they were maybe thirteen or so, but she’d become increasingly bad at guessing the ages of children. She always guessed too young – her own son, Ryan, was twenty, and although he looked like a man, she felt sure he could really only be ten at the most. Surely. Had time gone by so fast?

‘Pairs,’ the teacher said again. She looked young, too. Out of nowhere, Moira thought of her husband, Jackie: he’d been a teacher when she first met him. He’d taught PE to kids this age for decades, and she could imagine him making the same sing-song chant as this young woman. She tried to picture him: the young, lean man he’d been when they met, and found that she couldn’t. It hasn’t even been that long, she thought. I can’t lose him yet.

As Moira blinked away her tears’ warning sting, she realised the young, blonde teacher was speaking about her. She pointed down the steps at Moira – the pointing hand weighed down by a massive, turquoise-coloured ring. ‘Kids, this lady wants to come in.’

Moira flinched.

‘Oh no, I don’t,’ she sang over the heads of the children. Then she laughed, because it was true. But the mob did begin to trickle over to one side of the steps, and form a vague line.

Moira dithered. The ring on the teacher’s hand looked like the lurid, sugary gobstoppers Ryan used to whine for in the corner shop, back when he really was ten years old. The children in front of her seemed to bear no resemblance to him, though – to the kids he’d been in school with. Children – and especially older children – seemed so much tougher, more streetwise, these days. The girls lounging on the steps before her all wore the same black, elasticated leggings, tiny skirts stretched over them so tight that Moira could see which girl was wearing lacy lingerie, and which was wearing piped cotton. She blinked and blushed, feeling like a pervert and a pearl-clutching granny all at once.

‘Come on in,’ the teacher called, over the heads of the chattering line.

But the boys at the top of the mock-marble steps were shoving and elbowing. Moira watched one of them take a slow, calculated look over his shoulder, and then swing out backwards, slamming his weight into a smaller boy on the step below. The big kid kept his hand firmly on the banister, making sure that he didn’t fall – but his victim careened sideways into empty space, landing with a clatter and smack on the hard staircase.

‘Jason!’ The young teacher barked out the name in a way that sounded well practised. Moira winced, looking at the young man now sprawled on the steps. Another Jason, she thought. The bad ones are always called Jason – something Jackie used to say.

She turned away from the steps and the library, walking quickly until she had left behind the snickers of the tight-skirted girls. Moira thought of that boy’s mother – how later, her kid would likely come slamming home morose, silent, and pound up the stairs without looking at her. Had that mother also given up asking what happened? Had she too begun to assume that this was just the man her son was growing into? And did she also, in moments of barefaced honesty, suspect that her own behaviour might be to blame?

Again, Moira blinked the sting from her eyes: stop it. She’d essentially just bunked off school, and it was a beautiful day. Don’t waste this.

Across the street was an orange-fronted sandwich shop, not much more than a fridge and a space where two or three people could stand. Moira ordered a BLT with mayo – old-fashioned, she thought, scanning the fridge’s display of quinoa, hummus and pomegranate seeds – and swung the meal in its brown paper bag as she paced up the ramp into Greyfriars Kirkyard.

This was a popular picnic spot: office workers in smart clothes sat in ones and twos on the grass, some with their shoes kicked off. A knot of people took it in turns to snap photos at the grave of Greyfriars Bobby, and to add to the pile of sticks left as presents for his canine ghost. Moira veered away from the kirk itself, heading downhill along the pea-gravel path. Her breath caught in her chest. A slim, vigorous laburnum tree blazed over the path in front of her: its vivid yellow blooms hung so thick that they bent the branches groundward in graceful arcs. She couldn’t believe no one was down here, photographing this. She fished out her mobile, and thumbed a couple of photos of her own. They didn’t do it justice.

Clutching her lunch, Moira ducked under the laburnum’s branches and settled herself on the grass at its foot, leaning back against the trunk. It wasn’t a comfortable seat, but the sunlight filtering through the tree’s canary-coloured blooms made her feel warm and safe. Like sitting in her own miniature cathedral, or – Moira smiled – one of those plastic snow globes filled with glitter instead of snow. She chewed on her sandwich and looked out across the kirkyard. Many of the headstones were disintegrating now, having borne centuries of Edinburgh’s famous sideways rain. Some had fallen face down on top of their graves. But in sheltered spots, there were still a few intricately carved gargoyles, winged and grinning skulls, hourglasses . . . even the occasional angel. The fancier Edinburgh families had crypts, sunk into the grass – ironwork grilles protecting underground rooms where no one living had set foot in years.

A peal of laughter clattered across the kirkyard, and Moira looked up. A boy of about Ryan’s age was sitting on the roof of one of the crypts, swinging his legs off the lip of the doorway. Across from him, a girl with pale-coloured hair balanced atop a headstone, her back turned to Moira. She’d stretched over the pathway to pass the boy something, and it had dropped onto the gravel below. The graveyard rang with their laughter: the laughter of two people who were very drunk, or perhaps high on some substance or other. Moira watched as the boy climbed gingerly down from his vantage point – his tender dance on the gravel below made her realise he wasn’t wearing shoes. The thing he retrieved was white, and he cradled it in both hands like a kitten. It was, Moira realised, a half-wrapped fish supper. He picked his way across the path, and handed it up to his girlfriend, waving away what seemed to be an offer to share. They looked radiant, the two of them: lit up in the sunshine, framed by shifting yellow blossoms, and young, so impossibly young. The boy stood at the base of the headstone, rubbing his girlfriend’s feet as she ate – even at this distance, Moira could see that apart from his bare feet, the boy was well dressed, smart. Sunlight flashed off his glasses. The girl’s kicked-off flip-flops were splayed on the grass below, near where the meal had fallen. Moira quietly gave thanks for her steady hands, holding the sandwich in its clean, brown paper.

She wandered out of the kirkyard dazed, everything a little too bright outside the laburnum’s golden cocoon. She turned right, passing shop-fronts with their windows dressed for summer: sunhats, gauze scarves, sandals with rainbow-jewelled T-bars. I’m walking to work, Moira thought. But it was nearly a year since she had taken early retirement – two years since Jackie had died and his life insurance had allowed her to – and far longer since she’d worked here. And of course, when she turned the corner, the old Royal Infirmary looked nothing like it had when she’d walked here every day as a young staff nurse. Behind the original sandstone hospital buildings, the developers had stacked up blocks of flats that looked to be made entirely from glass. On the lower floors, twenty-foot blinds hung from the ceilings to keep out prying eyes. But the topmost floors seemed to have no curtains or blinds at all: they were transparent boxes, open to the sky. Moira sighed. She was glad that her old workplace was being put to good use, now that the new, state-of-the-art hospital had become established in the suburbs of Little France. She just wished it had been turned into something more accessible: a brief internet search had told her a while back that even a studio in the development would cost nearly a quarter of a million.

Moira crossed the street, and stepped into the patched shade of the sycamores at the entrance to the Meadows. There were no gates here, but there was a sandstone monument built to mark the entrance: tall as a bungalow, a stone unicorn carved at the top. Moira gave the unicorn a very slight nod, as she always had, walking to and from the Infirmary each day. She remembered Jackie again – little scraps of him seemed to be everywhere today – standing in the shadow of that monument, waiting for her to come out of work so they could go to the pictures, or walk through the park to the ice-cream parlour. She could pick out his tall, wiry figure a mile off, even in the dark, with the orange streetlight slanting over his shoulder and hiding his face in shadow. That was the way she saw him now: half obscured by time’s fallen curtain. She thought she’d been so careful, too – trying to preserve every memory.

She idled down the hill a little troubled, passing through the park, along the east side of the old Infirmary site. She stepped into a little flagged courtyard, with saplings planted in square beds, and angular, dark-coloured marble benches. This both was and was not a place Moira recognised. A lot of the so-called modern buildings that had made up the hospital had been torn down: only the listed sandstone remained. She sank onto one of the hard benches, tipping her face upwards as though trying to hear the memory that was forming. She thought about the night shifts she used to do in summer, coming on in the evening – finding herself climbing the stairs yet again because the lift was full or broken or just too slow – and stopping for a moment on a high landing. Those long summer evenings, the last of the light would stream in off the park, slightly green, and dust from the hospital’s bodies and blankets would swim in shimmering eddies up and down the stairs. She’d treasured those small, still moments in the midst of a chaotic shift. She wondered now if she’d lost the ability to feel things as keenly as she used to as a young woman: that perhaps it was age that kept her from properly remembering Jackie, from properly committing to her OU course, or from talking to Ryan about why he was so moody these days. Even now, lounging on a bench in a pretty courtyard, on a beautiful late spring day with absolutely nothing in the world that she needed to do, Moira still didn’t feel as calm and whole as she once had, pausing mid-shift in that stairwell.

She could hear an ambulance somewhere. At first, she wondered if the sound was inside the memory; ambulance sirens had been a big part of the general background noise in this place. Perhaps it was a ghost ambulance, hanging around the old building where it had drawn up so often. But no – Moira’s more logical mind kicked back in. It was somewhere behind her, held up at the Tollcross junction, perhaps, and moving closer.

The siren grew louder until it felt like the vehicle must be almost on top of her. Moira half expected it to screech round the corner and into the little sheltered square. She could hear the engine now, as well as the siren – it could be only metres away. She’d learned as a nurse that there was nothing quite like the sound of a siren to grab the attention of passers-by – that there’s something in human beings that is drawn to screams and spatter and tragedy. People want to see what will be wheeled out of the back of an ambulance. They want to see it happen to someone else, because if it’s happening to someone else, it isn’t happening to them. But even as she had this thought, Moira found herself rising, and walking towards the sound.

As she rounded the corner, the siren was shut off, and the back doors of the vehicle were being banged open. Three young men in fluoro vests and hard hats were shouting at the paramedics, telling them to hurry, gesticulating with wide-open arms. They all looked very young, Moira thought. She loitered at the corner of a building, trusting that her middle-aged-woman status would keep her from being seen. The workmen all had tool-belts strapped to their waists, and as they hustled the paramedics and stretcher into the building site, the D-rings and instruments jingled like chunky chatelaines.

I should leave, Moira thought. A couple of other people had stopped to gawk, and she realised how distasteful it looked. But she didn’t move. She looked up, past the hoarding, at the visible bits of the building site sticking up above. There was a huge pile-driver, bright yellow and oddly gallows-like with its supporting struts. A massive crane swung in the air, visible only in bits between the buildings. She could see part of its latticed central mast, and the ladder inside, which a man was now slowly climbing down. Clearly, all work had stopped. This crane operator looked tiny – the drop, if he fell, was massive. Moira felt a prickle of fear: there were so many horrible ways to be hurt in a place like this. Did she really want to see what might be brought out to this ambulance?

It was too late to move. The paramedics came rattling back into view, trailing their patient on a stretcher. For a moment, she forgot how to breathe. On the stretcher was a dark-haired young man – same fluoro vest, same tool-belt – the upper right corner of his body impaled by an iron-coloured rod.

‘Ryan,’ she heard herself say. It wasn’t – the boy didn’t even look that much like her son. But he was about the same age, the same build, and just for a second her imagination superimposed her son’s face over the face of this stranger. His teeth were gritted hard, she could see. Even with a starter bar jammed through his shoulder, he was determined not to cry out. To be brave.

‘Wait, you know that kid?’ Another of the rubberneckers – a young woman with blonde hair, young enough to be a student nurse – appeared at Moira’s elbow.

‘No,’ Moira said, unable to pull her eyes from the stretcher, ‘no, I just—’

But the girl had already started towards the ambulance, waving an arm to get the paramedics’ attention.

‘Hey!’ she was shouting. ‘Hey! There’s a woman here who knows this guy!’

The two men were bumping the stretcher into the ambulance. The one at the back, still out in the open air of the site, poked his head round the vehicle’s open door. Moira flinched. She ran after the girl, the two of them arriving by the ambulance at the same time.

‘Listen,’ Moira said, ‘I’m sorry.’

‘You know this man?’ The paramedic looked exhausted, but then, she thought, they always did.

‘No,’ Moira replied, unable to meet his eye. She made the mistake of looking into the ambulance instead, where the young man – now sheltered from the collective gaze of his workmates – had begun to hiss in pain, pulling quick, ragged breaths through his teeth.

‘She’s mistaken,’ Moira said. She looked hard at the girl – perhaps too hard, because she shrank away behind the open door of the ambulance, and out of sight.

‘I – I’m a nurse.’ Moira’s face burned. As if this information could do anything to explain the last thirty seconds.

The paramedic raised his eyes heavenwards. She wanted to apologise to him – she wanted to apologise over and over, to grovel – but she couldn’t form the words.

‘Sorry, love,’ he said, ‘but I think we’ve got this covered. I need you to stand clear right now.’

He swung himself up into the ambulance, and slammed the door. Moira leapt back as the siren started up again, clanging in her ears. The driver turned the vehicle neatly around and then it sped off, kicking up a brown haze of building-site dust.

Moira stood listening to the siren as it moved off through the city. To stave off the crushing embarrassment she felt, she tried to imagine the route it might be taking to get the boy to Little France. She listened as it looped round the far end of the Quartermile, and then onto the long drag of Lauriston Place, where it could pick up speed. But beyond that, she lost the thread of the journey, and could only listen as the wah-wah-wah got slowly quieter, swallowed by traffic noise.

Looking up, she saw that the trio of workmen had returned, and were doing the same as she was – standing still and quiet with their heads cocked, listening. She tried to imagine what she must look like to them, with her mousy wash-and-go hair and the same faded jeans she’d worn while she’d been pregnant with Ryan. They’ll just think I look like someone’s mum, she thought. Someone’s mum, someone’s wife: nothing to identify her but the wedding ring her dead husband had given her. Moira cursed herself for having said her son’s name at that crucial moment, for pulling the attention of the paramedic towards her, and away from the suffering boy. She imagined his mother, probably hard at work somewhere right now – tapping away at a laptop, or chairing a meeting. That woman had no idea, but she was about to get a terrible phone call. Then Moira remembered the boy from earlier – the little boy, who’d been pushed down onto those hard stone steps. She straightened, giving her head a shake to dislodge the last of her embarrassment. She turned to walk back the way she had come, now with a purpose for the rest of the day: whether he liked it or not, it was time. She’d left it too long, but no longer. She was going home to talk to her son.

13 May, 4.55 p.m.

When Helen Birch finally arrived at Gayfield Square, Banjo Robin was standing out front, as though waiting for her. She’d hoped the dappled shade thrown by the square’s trees might turn her into just another anonymous pedestrian, but as she approached she realised he’d clocked her. She pulled in a long breath and steeled herself for the verbal barrage, which she guessed would begin when she was about twenty paces away.

‘Don’t start, Robin,’ she said, as she reached his earshot. ‘I don’t work here any more, okay?’

She might as well not have bothered.

‘Ken what, hen? This time youse’ve really fucked me over. Like pure fucked me over.’

Banjo Robin was a local pain in the ass. He was somewhere in his early sixties, and ran with a crowd of similarly aged folk musicians who were what the official documentation would call vulnerably housed. They weren’t homeless as such – Robin had a girlfriend in every postcode district, and lived with whichever one he hadn’t yet punched that week – but they were of no fixed address. On the rare occasions when he was sober, Robin was startlingly adept at the banjo. Problem was, he liked to top up his busking money by slinging illicit substances. They were usually dubious in quality and minuscule in quantity, which was how he’d managed, thus far, to avoid the jail. But he was a regular visitor to the drunk tank. When a call went out about a sixty-something man urinating in the street, loitering suspiciously around parked cars or shouting obscenities at some woman’s lit window in the small hours, it was highly likely that the attending panda car would return from its drive-by with Banjo Robin in the back seat.

Unsurprisingly, he knew all the officers at the Gayfield Square and St Leonard’s stations by name.

Right now, he was babbling. Birch drew level with him and held up one hand, palm flat, as though trying to stop traffic.

‘I mean it,’ she said. ‘Don’t tell me, I don’t work here any more. If you want to talk to someone, you can come inside.’

He made a huffing sound.

‘Been inside,’ he said. ‘Cunts willnae dae anything.’

He began patting himself down, and with shaking hands fished a tobacco pouch and rolling papers from somewhere about his person.

‘Am I right in thinking,’ Birch said, as he began pinching little hairs of tobacco into a meagre cigarette, ‘that my colleagues in there have asked you to leave?’

‘Naw.’ Robin put out a thin, grey tongue to damp down the cigarette’s long edge. ‘Well, aye, but that’s no fucking fair, I mean, is it? I mean is that even fucking . . . professional?’

Birch couldn’t help it: she rolled her eyes.

‘Okay. Well, if they’ve refused to help you in there, and they’ve asked you to leave, then there’s really nothing I can do. You should go home now, Robin.’

‘See that’s the hale fucking problem,’ Robin replied. He paused, and tried in vain to light his cigarette: the lighter sparked and sparked and sparked. ‘I dinnae have a hame. Bee fucking threw me out, for nae fucking reason, and then called you lot on me.’

Birch shook her head. She’d met Bee, the Tollcross girlfriend, a couple of times years back, attending Robin’s domestic disputes. She’d seemed a nice, gentle sort of woman. She had a pretty north-west-coast accent, hennaed hair and several cats. Why she put up with this bozo time and again was anyone’s guess.

‘I’m going in now,’ Birch said. ‘I’d advise you not to follow me.’

The lighter finally caught. He grunted at her as she moved past him.

‘Good luck, Robin,’ she said. Funny, she thought. I might even miss him.

The lobby was dim, though strip-lit. The station was a low, modern-ish building that had been wedged in between rows of tall, old tenements. Those big trees out in the square didn’t help. The only natural light that got in was thrown in odd oblongs over the floor, reflecting off the hi-vis police vehicles parked up outside.

‘Arright, chuck.’

Birch turned.

‘Hello, Sergeant,’ she said.

Al Lonsdale had known Birch longer than anyone else here. He was one of the custody sergeants, and right now he was standing to the extreme left of the lobby’s glass doors and peering out through them – sideways, like a kid playing hide-and-seek.

‘Keeping an eye on Banjo?’ Birch asked.

Al nodded.

‘Just want to make sure he goes his merry way, the slack bugger.’

Birch smiled. Al was from Wakefield, but decades of living away from that city had failed to knock the edges off his accent.

‘We checked him in to his usual suite last night,’ Al went on. ‘Just your regular Banjo shenanigans – he’d had a skinful, of course. We ought to set him up with a loyalty card, he’s here that much.’

Al shuffled away from the door, and as he passed Birch, he looked into her face, twisting his head like an inquisitive bird.

‘You all right, love? You look a bit . . . off.’

Birch smiled and opened her mouth to speak, but Al rarely required a response.

‘Of course,’ he was saying, ‘I should be moderating my tone around you now, shouldn’t I? Now you’ve got your pips, and all that. I should be calling you Marm.’

Birch laughed. On Al’s tongue the word had no r in it – he sounded a little like a sheep, bleating.

‘Maa-m?’ she mimicked. ‘I’d rather you didn’t.’

Al grinned widely.

‘All right, Detective Inspector Fancyknickers,’ he said. ‘No need to take the piss.’

He made to slip behind the lobby’s desk, but Birch caught him by the arm.

‘I’ll miss you,’ she said. ‘I’m going to miss this old place a lot.’

They stood looking at one another for a second, Birch still holding on to his forearm. Then Al reached down and pulled her into a bear hug. She sniffed.

‘Arright, arright,’ he said, his voice muffled against her hair, ‘no need to get all soft about it.’

Over his shoulder, Birch noticed the pile of boxes she’d asked to be brought down for her.

‘That’s enough now,’ Al said, opening his arms. ‘Any longer and I could have you for sexual harassment. And me old enough to be your dad.’

Birch’s face hurt from smiling while trying not to cry.

‘That’s not super politically correct of you, Al,’ she said.

He shrugged.

‘Well, you know – all this equalities legislation. It changes too often for us old-timers to keep up. Speaking of which, let me summon up some burly young man to help you with those boxes.’

Birch grinned.

‘I’ll be fine,’ she said. ‘The car’s not far.’

Al got in behind the desk.

‘You take what you can get now, missy,’ he said. ‘It’ll not be like this working at headquarters, you know. There’s no one’ll give you the time of day over there.’

Birch shook her head.

‘Hey, Sergeant,’ she said. ‘For a start, they don’t call it headquarters any more – we’re all equals now, remember? And secondly, it’s fine. They’re fine. They’ve given me a very nice welcome so far.’

Al gave one, sharp nod.

‘Aye, well, see that it continues. I don’t want to have to come down there and have a word with that chief inspector of yours.’

For a moment, Birch allowed herself to imagine Al storming into DCI McLeod’s office, sworn to defend her honour. She was still smiling, but the smile was weak. Al was right. The new place did feel impersonal. Shit. Have I done the right thing?

But Al had the phone receiver lodged between ear and shoulder.

‘You just stand there and look decorative,’ he said to Birch. ‘I’ll have a dashing young constable down here in a jiffy. Least we can do on your final visit, eh?’

The boxes were filled with stuff that needed sorting out – had needed sorting out for years. She’d collected them last because she’d been putting it off. Now they were slung in the back of her car, the seats pulled down to accommodate them. The last tie she’d had to the station at Gayfield Square was loosed.

Al had got a janitor, in the end, to help her with the boxes. The poor guy had made the mistake of wandering into the lobby, and Al had exclaimed, ‘Just the man!’ He may have been right: the janitor had found an old moving trolley, which – though it gave him some difficulty outside on the cobbles – did make for a quick job.

‘You hear about that kid?’ the janitor had asked in the space between hefting one box into the car and lifting another. ‘The one who got impaled?’

Birch blinked.

‘Impaled?’

‘Aye. Got the radio on in my office and they said, wee gadge working on a building site up town falls ten feet off, I don’t know, something. Ends up with a starter bar running right through him.’

‘Ouch,’ Birch said, and then, after a pause, ‘What’s a starter bar when it’s at home?’

The janitor made a gesture in the air.

‘They stick up about so long, out of foundations on buildings. They’re sort of twisty. Like an old-fashioned butterscotch cane, ken? Maybe you’re too young to remember those.’

Birch was plenty old enough, but didn’t say so.

‘Oh okay, I know what a starter bar is. Poor kid.’

‘Aye.’ The janitor looked at her with what might have been suspicion. ‘Surprised you didn’t hear about it, on your police radio or whatever.’

‘Oh,’ Birch said. ‘I’ve not been very gettable today. But it’s likely someone from this place did attend.’ She nodded backwards towards the station. A thought struck her.

‘Is the boy dead?’ she asked.

The janitor hauled another box off the trolley, and planted it with a rattle in the back of the car.

‘Not yet,’ he said.

Now, as she drove home, Birch had no difficulty keeping her mind off the boxes – the impaled boy loomed large in her imagination.

Please don’t let that come across my desk, she thought – and the thought came back over and over, like a mantra. Sounds like a potential nightmare.

But she was also thinking about what the accident must have felt like for that boy. A quick Google on her phone before she’d started the engine had told her he was only twenty. My brother’s age, she thought, though it wasn’t true. In her mind, her brother Charlie was forever twenty. In fact, he’d have celebrated his thirty-fourth birthday that year, had he still been around. She imagined the building-site boy framed inside scaffolding, his back to the terrible drop, working away on something, thinking his own private, mundane thoughts. In her mind he was handsome, as all twenty-year-old boys are – in a gangly way that they themselves have never noticed. She imagined he had Charlie’s face. And then she imagined him falling. Flying backwards as th

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...