- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

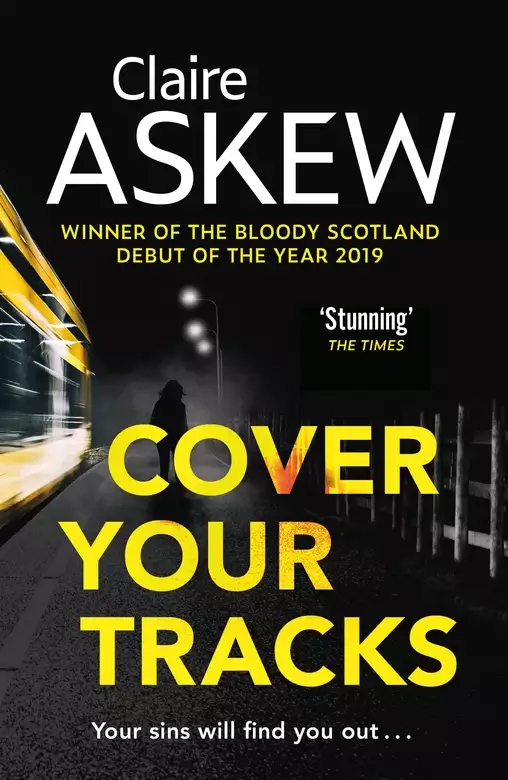

Claire Askew won the Scottish Debut Crime Award with her debut All the Hidden Truths, praised as 'A meticulous and compelling novel' by Ian Rankin.

'What if I told you,' he said, 'that I believe my mother's life to be in danger?'

Robertson Bennet returns to Edinburgh after a 25-year absence in search of his parents and his inheritance. But both have disappeared. A quick, routine police check should be enough - and Detective Inspector Helen Birch has enough on her plate trying to help her brother, Charlie, after an assault in prison. But all her instincts tell her not to let this case go. And so she digs.

George and Phamie Bennet were together for a long time. No one can ever really know the secrets kept between husband and wife. But as Birch slowly begins to unravel the truth, terrible crimes start to rise to the surface.

Beautifully written and ingeniously plotted, Cover Your Tracks confirms Claire Askew as a major new talent in crime fiction.

(P) 2020 Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

Release date: August 20, 2020

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Cover Your Tracks

Claire Askew

It wasn’t that DI Helen Birch hated Monday mornings, per se. She just wished they didn’t have to be so full of emails. Every Monday morning, she drove towards her office at Fettes Avenue police station with a mounting petulance: she didn’t want to do emails. She had so many other things to do. It wasn’t fair. It certainly wasn’t what she’d signed up to the police force for, over fourteen years ago. And on this particular Monday morning, she’d rather have been anywhere other than in front of her computer screen. It was the second day of September, and still summery. Leaving her little house on the Portobello promenade earlier had felt like a real bind, with the sun already shining full on the beach and the wet sand reflecting it back in stripes of pinkish gold. As she’d driven through town, Birch had passed fluorescent-vested men working in teams to take down Fringe Festival posters and dismantle hoarding. Edinburgh was basking in a quiet, post-Festival glow.

‘And what have I got to do?’ Birch muttered to herself as she flopped into her office chair. ‘Bloody emails, is what.’

She nibbled at the edge of her cardboard coffee cup as she waited for the inbox to load, and show her this Monday’s figure of doom. Seventy-six unread.

‘Really?’ Birch leaned forward and squinted at the number. She hadn’t misread it. ‘Haven’t people got better things to do with their weekends?’

‘Everything okay, marm?’

Birch jumped, then felt herself blush. She’d been caught talking to herself. ‘Jesus, Kato. You ever thought about switching to the other side? You’d make a great cat burglar.’

DC Amy Kato was standing in her office doorway. ‘Sorry,’ she said. ‘I did knock.’

Birch blinked. Amy was wearing her trademark high heels. She must have made a racket, in fact, walking up to the door.

‘Seems I was miles away,’ she said. ‘But don’t worry, nothing’s up. Just . . . having a coffee and feeding my resentment over the great injustices of this life, you know?’

Amy smiled, but then frowned, worried that her boss might not be joking. ‘Yes, marm.’

Birch laughed. ‘Ignore me,’ she said. ‘I’m just being daft. What can I do you for?’

Amy glanced back over her shoulder. ‘I’ve just come through reception,’ she said. ‘There’s a bloke downstairs wanting to report two missing persons.’

‘Two?’

‘Yeah, that’s what he said. Desk sergeant’s sent me up to find someone to talk to him. He says he’ll only speak to someone senior. He seems a bit . . . well, belligerent.’

Birch rolled her eyes. ‘Oh great, one of those.’

‘’fraid so, marm. And you seem to be the only DI in the building who isn’t terribly busy.’

Birch fluttered her eyelashes at her friend. ‘Who, me?’ she said. ‘I’m busy! I’m tied in absolute knots, in fact.’

Amy grinned. ‘You literally just said you were sitting drinking coffee and . . . erm—’

‘Resenting the great injustices of this life, yes, Kato. That’s very important work.’

‘I don’t doubt it.’ Amy was still grinning, but she’d begun to back out of the door again, beckoning Birch to follow. ‘I’m just not sure this gent downstairs would see it that way.’

Birch downed her coffee. ‘All right, all right,’ she said. ‘I’ll just nip to the Ladies and make myself look a little more senior. Tell this guy – what’s his name?’

‘Robertson Bennet.’

Birch raised an eyebrow. ‘Wow, okay, quite the handle. Tell him I’ll be down in five.’

Birch flopped down the stairs, having tucked some stray wisps of hair into her ponytail and wiped the lipstick off her front teeth. Waiting for her in reception was perhaps the widest-set man she had ever seen. He wasn’t fat, rather his body looked triangular: huge shoulders and a barrel chest tapered down to a pair of surprisingly small feet. He was also ginger-haired, though more tawny than carrot-topped. He was well groomed, but looked about as Scottish as it was possible for a person to look.

‘Mr Bennet?’

The man looked in her direction. Birch walked across the lobby, her hand extended.

‘DI Helen Birch,’ she said. ‘I came down as soon as I could.’

With some difficulty, the big man unfolded himself from his chair. These days, thanks to Anjan, Birch knew a made-to-measure suit when she saw one. She also noted the giant Rolex on Mr Bennet’s wrist.

‘At last,’ he said, and shook her hand. ‘Robertson Bennet.’ The man paused, and then, as if he couldn’t help himself, added, ‘ReadThis CEO.’

‘Pleased to meet you,’ Birch said. She glanced over at the desk, catching the eye of the custody sergeant on duty.

‘John,’ she called over, guessing at the name and apparently getting it right, as the sergeant looked up. ‘Do you have a room free?’

Robertson Bennet didn’t seem too impressed by the tiny meeting room Birch had squeezed him into, and he sighed his way through her preliminary questions about his own personal details.

‘In the event that we open a case on this, we need to be able to contact you,’ she said, trying to keep her voice light. ‘I promise you, this is standard procedure for everyone, Mr Bennet.’

Bennet huffed a final time, but coughed up the required information. His accent was unusual: he was Scottish for sure, but with an American inflection. Some of his ts came out like ds. The home address he gave was in California.

‘Now,’ Birch said. ‘I’m going to take notes while you talk, and I may well ask questions as we go to make sure I have all the information I need.’

‘That’s fine.’

‘Great. So, tell me why you’ve come in to see us.’

The man shifted in his seat, settling, showing her he meant business. ‘I want to report two missing persons,’ he said. ‘My parents. They’ve both disappeared.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that,’ Birch said. She was doing maths in her head: Bennet’s date of birth made him fifty-eight, though he looked younger. That meant his parents could be pretty elderly. ‘Can you tell me the last time you saw your parents, or had contact with them?’

‘Yes: 1986.’

Birch blinked. She’d been expecting him to say last week. ‘Nineteen eighty-six,’ she said, stringing the words out a little, to check she’d heard him correctly. ‘Over thirty years ago.’

‘That’s right. We’re, ah, we have been . . . estranged.’

Birch was trying not to make a face at the man. Is this a wind-up? she wondered. But no: Bennet looked serious.

‘Tell you what,’ she said. ‘I’m just going to let you talk for a bit. Tell me what’s happened.’

‘Well, basically . . . I’m a computer nerd, Detective Inspector,’ Bennet said. Birch tried to keep her expression even: this wasn’t where she’d expected him to start. ‘One of the original nerds. Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, all those guys – I’m one of those guys.’

Oh God, she thought, this is a wind-up. But Bennet was still speaking.

‘This all started,’ he said, ‘because as a teenager I was all about computing. I read up about it in the library, could see the potential where most people couldn’t – my teachers, the school careers adviser, they all thought it was a fad. I wanted to build robots, that was the dream, had been ever since I was a little boy. So I knew I needed to get into computer programming. When I left school I decided I was moving to the USA. That was where it was all going on back then. My parents were dead against the idea. They were sheltered folks, and they had ambitions for me that they thought were grand: teacher, accountant. They didn’t believe that robotics engineer or computer programmer were real jobs. They were small-minded people, and we got into a lot of fights.’

Birch was nodding. She couldn’t really see where this was going, but Bennet didn’t show any signs of pausing, so she let him speak on.

‘I was still living under their roof in my mid-twenties, and I’d had enough. I was doing menial, meaningless jobs, earning barely anything. They made me pay rent – rent, to live in the family home – deliberately, I think. They didn’t want me saving enough money to move to America. But one day, after a particularly bad fight, I’d had enough. I went to the building society and talked the clerk into letting me empty my father’s account. I used the money to buy a one-way ticket to California. San Jose, to be precise. Silicon Valley.’

‘You stole from them.’ Birch gave him her best let me remind you that you are speaking to a police officer face.

‘Borrowed,’ he said. ‘I even said that to them at the time. That I was going to make something of myself in the US, and I’d be able to pay them back a hundred times over. They didn’t understand.’

He waited, as though expecting Birch to reprimand him. Once upon a time she would have done, and would have reprimanded his parents, too: she used to hate cases where people failed to report obvious, open-and-shut crimes. But these days – thanks to her little brother, Charlie – she felt less able to pass judgement. She understood the logic of covering for a family member.

‘So you left.’

‘I did. That was 1985. I tried to keep in contact with them for the first few months – called home a couple of times, and then later I wrote letters. My mother would talk to me if my father was out, but if he was there he’d make her put the phone down. I never got a letter back from either of them.’

Birch made a note, in shorthand: mother forgave him, father did not. ‘Then what?’ she asked.

At this, Bennet’s face lit up. He sat back in his seat, and spread his hands. He suddenly looked rather like a Bond villain. ‘I made it big, Detective Inspector.’

‘In . . . robotics?’

He laughed. ‘No. No, I never did get to live out my childhood fantasies. I went to work for Xerox, initially.’

‘The photocopier people?’

He laughed again, and pointed a finger at her. Good one. ‘That’s what they’re famous for now, but in the eighties they were all about programming. I worked with them alongside 3Com on Ethernet.’

Birch realised her face must have gone blank.

‘Don’t worry,’ he said, ‘most people react that way. I worked in . . . connectivity. The early internet. After a while I moved to 3Com itself, then I went solo. Got into dot-coms in the nineties and made my first big money, then went on to start-ups after the bubble burst. These days I’m an apps man.’

Birch’s head felt like it was spinning. ‘Okay,’ she said. ‘I should tell you I can barely work my phone. Is it important that I understand this stuff?’

Bennet’s smile faded a little: he’d encountered a Luddite. ‘Not at all,’ he said. ‘In fact, I ought to get back to the point. My parents.’

‘Yes.’

‘I tried to get back in touch with them, in the early nineties. By that time I’d stopped the calling and the writing. I was busy, and I guess I was mad at them, too, for not understanding. But I decided to get back in touch and pay back what I’d borrowed.’

Stolen, Birch thought, but she didn’t say anything.

‘I called their home number but they never answered. I wrote. I asked them how I could wire them the money. I wrote maybe four times. I never got any reply.’

‘And after that?’

Bennet drew himself up a little taller in his chair. ‘After those four or so letters, I stopped,’ he said. ‘I figured they’d made their decision. They’d cut me off. They didn’t care that I’d done it, that I’d made my way in the world like I always said I would. They never wanted that for me.’

My heart bleeds, Birch thought, looking again at the man’s tailored suit, diamond-studded watch, spotless brogues.

‘That was the last contact I ever made, or tried to make,’ he said. ‘Until now.’

Birch scribbled a note. ‘That was the early nineties, you said? Any chance you remember what year?’

‘It was 1992,’ Bennet said. ‘Maybe.’

‘Okay, Mr Bennet.’ Birch took a deep inhale. ‘Now you’ve decided to make contact with your parents again, can I ask . . . how extensively have you looked for them?’

The man frowned. ‘What do you mean?’

‘Well, given that you haven’t seen them in over thirty years, isn’t it possible that they’ve simply moved away? Rather than being officially missing, I mean.’

Bennet blinked at her. ‘Well, I hoped you’d find that out for me.’

She fixed him with a look. ‘With respect, Mr Bennet,’ she said, ‘you’ve come to Police Scotland, not Friends Reunited.’

Stop it, Helen, she thought, you’ll end up with a complaint made. But to her surprise, the man smiled.

‘Lordy, your tech knowledge really is rusty, isn’t it, Detective Inspector? Friends Reunited? Really?’

Birch realised she was blushing again, and hated herself for it. ‘What I mean is,’ she said, ‘finding out where people have moved to in recent times doesn’t really fall under the sort of investigative work we do. Perhaps American police officers have the resources at their disposal for such things, but I’m afraid we really don’t.’

Bennet sighed. ‘I’ve done all I can to find them,’ he said. ‘I’ve visited the house. The people living there now have no forwarding address. The real estate agent who sold the house won’t tell me anything because of your data protection laws over here. I’ve tracked their online presence, both of them, not that it amounts to much. They don’t seem to have active social media accounts, no surprise there.’

‘Do you have siblings?’

‘Only child,’ Bennet said.

‘Aunts, uncles? Friends?’

He shrugged. ‘My mother had a sister, but she died when I was a kid. I’ve found a handful of the friends I remember my father having – found them on Facebook, I mean, and tried to get in touch. No dice: mostly their accounts haven’t been logged into in years, so they haven’t seen my messages, or if they have they don’t seem to want to talk. No doubt my parents let them know their side of the story. Maybe they’ve all just died.’

Birch winced. ‘I was going to ask, Mr Bennet,’ she said. ‘I’m sorry to have to do so, but – is it possible your parents could be deceased? I imagine they’d be quite elderly now.’

‘Don’t be sorry.’ Bennet waved a hand. ‘It was the very first thing I checked myself. But I can’t find any death records, any obituaries. Nothing like that. They’ll both be in their eighties now, so, sure, I knew that was a possibility. But they’re not dead, more’s the pity.’

Birch started. Bennet noticed, and let out a short laugh, as though trying to pass the comment off as a joke.

‘Why do you say that, Mr Bennet?’ Birch rolled out the you’re speaking to a police officer face again.

Bennet squirmed. He held up his hands. ‘All right, all right,’ he said. ‘It’s about money, okay? Everything seems to be about money when it comes to my parents. I haven’t been back in Scotland for thirty years or more, never wanted to be – pardon me for saying this, Detective Inspector, but it’s a damned parochial country. So no, I’m not here for some tearful reunion. The fact is . . .’

He was sweating. Birch glanced at the box of tissues on the table between them, but thought better of suggesting he wipe his brow.

‘The fact is,’ he said, ‘I’m here for my inheritance, okay?’

Chapter 2

‘So how did you leave it?’

Amy was sitting on the other side of Birch’s desk, warming her hands around a polystyrene cup of canteen soup. She was so engrossed in the story that she hadn’t so much as taken a sip, though her lunch break was almost over.

‘I sent him away with a flea in his ear,’ Birch said. She glanced up at her office door for about the sixth time, checking it was still closed. ‘Told him his parents were probably in a lovely retirement home somewhere, having a grand old time.’

‘If that’s the case, a private investigator’s what he needs,’ Amy said. ‘Not us.’

Birch nodded. ‘I did hint at that,’ she said, ‘though not in so many words. But I also said that people have a right to privacy. He was a bit upset about data protection. I think he thought he’d be able to sweet-talk people into telling him more than he’s entitled to know.’

Amy did a theatrical eye-roll. ‘Americans,’ she said. ‘Plus, he works in tech, right? The internet? Those guys like to think they can poke into anyone’s business. It’s creepy. I’d swear blind that my phone listens to me. Like, I’ll mention something really random to someone, something I haven’t thought about in years or typed into a search engine maybe ever, and what do you know? The next time I open Facebook there’s an ad in the sidebar for that exact thing. It freaks me out.’

Birch grinned. ‘The wonders of modern technology,’ she said. ‘But yeah, he seemed irritated that his parents weren’t, I don’t know, putting their wee caravan trips to Troon up all over Instagram, or whatever.’

‘Now now, marm.’ Amy wagged a finger. ‘There’re plenty of older people on social media these days, doing all sorts of cool stuff, I’m sure. Don’t be ageist.’

‘Wouldn’t dream of it.’ Birch flipped open her sandwich, and wrinkled her nose. ‘But answer me this, Kato: why do they put cucumber in every single sandwich in that bloody canteen?’

Amy was frowning. ‘I wouldn’t be surprised if they’d done it deliberately,’ she said.

‘The canteen staff?’

Amy’s frown disappeared, and she raised an eyebrow at Birch. ‘Sure, them too – but I meant Bennet’s parents. Maybe they made themselves un-findable. I sure as hell wouldn’t be interested in hearing from someone who’d nicked all my savings, only son or not.’

‘Hmm.’ Birch was thinking about Charlie again, of the things she’d forgiven her brother for. But not all families were the same.

‘Anyway,’ Amy said, finally taking a mouthful of her soup. ‘One less thing to add to the workload, eh, marm?’

Birch glanced up at the door again. ‘You’re not wrong,’ she said. ‘Like I say, none of this goes any further. I know it hasn’t turned into a case, but you know . . .’

‘Oh come on.’ Amy snorted. ‘You know you can trust little old me. If anyone asks – and nobody will – you told me nothing. He showed up, I came to get you, you talked to him, he left. I’m pretty sure anyone who saw him here would assume he was a crank anyway. That or a lawyer, dressed the way he was.’

Birch allowed herself to think of Anjan Chaudhry – her personal favourite lawyer – and smiled.

‘Oh don’t,’ Amy said. ‘You bloody loved-up types make me sick. Don’t you know I’m perpetually single?’

Birch laughed. ‘Single my eye. You’re out on dates every other night!’

‘Dating doesn’t mean you’re not single.’ Amy looked at her nails. ‘Perusing the menu isn’t the same as eating, is it?’

‘You’re terrible. Those poor men.’

Amy grinned. ‘It’s their own fault for being so disappointing.’

Birch waggled her eyebrows at her friend. ‘Maybe it’s your fault for being so picky?’

‘Pfft, nonsense. You may not realise this, but there aren’t all that many tall, smart, handsome lawyers around. You just got lucky.’

Birch tried not to preen. Amy’s dating record was, admittedly, disastrous. She opened her mouth to wisecrack back, but before she could speak, the phone on her desk rang.

‘DI Birch.’

It was John, the desk sergeant. ‘I’m sorry to bother you, marm,’ he said. His tone was pointed: he was saying it for someone else’s benefit. ‘But your . . . visitor, from earlier. He’s back at reception, and asking to speak to you again.’

Birch’s heart sank, and her face must have done the same, because Amy frowned at her and mouthed, What?

‘There in two shakes, John,’ she said, and put down the receiver.

‘Everything okay?’ Amy asked.

Birch dumped her sandwich on the desk, and stood up. ‘I’m afraid Mr Robertson Bennet is downstairs once more,’ she said.

‘Oh God. Persistent, isn’t he?’

Birch squinted at her laptop to check the time. Bennet had only been gone a couple of hours. ‘Looks to be,’ she said. ‘Come down with me, would you? I’d like a partner on this one, just in case things get . . . vexatious.’

Amy jumped to her feet, and a little splat of soup landed on her jacket sleeve. ‘Damn it,’ she said, swiping at the wet patch. ‘Sorry – I mean, with you all the way.’

This time, Bennet didn’t want to wait to be shown into another room. He began speaking as soon as Birch rounded the corner into reception.

‘What if I told you,’ he said, ‘that I believe my mother’s life to be in danger?’

Birch threw a glance to John: we might have trouble on our hands here. He took the hint, and stepped out from behind the desk.

‘I want to report my mother missing,’ Bennet was saying, his voice raised. ‘And I have reason to believe my father may have hurt her.’

Birch had crossed the lobby now, but Bennet didn’t wait for her to speak. Instead, he thrust his mobile phone out towards her, roughly at eye level. ‘A local news report,’ he said, ‘detailing that police were called to a domestic disturbance at my parents’ house, while they still lived there. My father was taken into custody, and my mother to hospital.’

Birch squinted at the screen.

‘In addition,’ Bennet said, ‘I have personal testimony, years of it. My father is a domestic abuser, and I believe that if something bad has happened to my mother, he’s at the bottom of it.’

He was still holding the phone in Birch’s face. She looked past it, fixing her gaze on him. ‘If that is the case, Mr Bennet,’ she said, ‘why didn’t you tell me earlier?’

Bennet lowered the phone. ‘Because I thought you’d help me,’ he said, ‘without needing to know that sort of personal information.’

Birch glanced around. Bennet didn’t seem to grasp the irony in the fact that he was speaking, loudly, in a public space that, along with police personnel, contained a handful of members of the general public. She tried, in her head, to accuse him of fabrication; of nipping out for an hour or so to spin a yarn that might make his case more credible. But she couldn’t.

‘Yes,’ Bennet said, ‘my tech company’s sinking. Yes, I need money. Yes, that’s why I came back to Scotland. But the longer I look for my parents and can’t find them, the longer I think about it, the more I fear that my father has done something to my mother. Something bad. I need to find out if she’s okay. And to do that, you have to let me report her missing.’

Amy was at Birch’s side. John was standing close to Bennet, having placed himself within cuffing distance. Birch looked at all their faces, Amy’s last. The Edinburgh Evening News article that was still visible on Bennet’s phone screen was dated 2013. A while ago, but not ancient history. Bennet’s mother would have been in her seventies then. In her seventies, and hospitalised by her husband.

Birch closed her eyes. Shit. ‘John,’ she said, ‘show Mr Bennet back to Room 03, will you? I’ll nip back to my office and get his previous statement.’

Bennet turned towards John, ready to be led away.

‘Here we go,’ Amy whispered.

Birch gave a grim nod. ‘Oh, and get him a cup of tea, will you, John? This may be a long interview.’

Chapter 3

‘George MacDonald,’ Bennet said. ‘M-a-c. Like the writer.’

This time, Amy was in the little meeting room with them, and she took the notes. She was faster at it than Birch, and used real shorthand, rather than Birch’s own half-made-up version. Birch, meanwhile, asked the questions, and scrutinised Bennet as he spoke.

‘You don’t have the same name as your father,’ she observed.

‘I changed it,’ Bennet said, ‘by deed poll. It wasn’t working for me in America. My birth name was Robert MacDonald. Sounds like a geography teacher. I needed something more . . . tech. More memorable. Google-able.’

‘Interesting,’ Birch said. The name-change sounded like vanity, but then, she’d never had any business sense. ‘And your mother’s name?’

She prayed it was something less ten-a-penny than George MacDonald.

‘Phamie,’ he said.

Amy paused in her scribbling. ‘Spell that for me?’ she said.

‘P-h-a-m-i-e,’ Bennet said. It’s short for Euphemia. But she never went by her full name, always Phamie.’

‘Maiden name?’ Birch asked.

‘Innes.’

Okay, thank goodness. There wouldn’t be all that many Euphemia Inneses around.

Birch nodded to Amy. ‘I have the last known address from Mr Bennet’s previous statement. Morningside, you said, Mr Bennet?’

‘Yes. It’s a terraced house, smallish. Nothing fancy.’

I’ll be the judge of that, Birch thought. Morningside was the city’s most affluent area.

‘Tell us about your father,’ she said.

Bennet took a deep breath. ‘Okay. Well, he was kind of an asshole. I mean, fathers were back when I was growing up . . . they’d got rid of the belt in my school, but you bet your ass it still got used in plenty of folks’ homes.’

Amy scribbled.

‘But in my dad’s case, it was manipulation. My mother didn’t work when I was a little kid, and she had no money of her own, except what he gave her. So he had power over her. She’d get worried sick about him, ’cause he was always disappearing. Sometimes just for an evening, and he’d come back late at night. But sometimes for days at a time. I think he did it just to scare her. Just to remind her that without him, she’d have no way to live.’

‘Where did he go?’ Birch asked. ‘Was he drinking?’

‘Sure, sometimes,’ Bennet said. ‘But no more than most men drink. Mainly he was down at the railway.’

‘The railway?’

‘He was obsessed with trains. He was one of those guys who stand on train platforms and write down when trains come in and go out. I think you still have them here, right? They must be real lone wolves now. But back then it was a hobby. My dad had a bunch of friends who did it.’

‘Trainspotting,’ Amy said, and Bennet laughed.

‘Yeah, that has a whole new meaning now, right? But I swear to God, that’s where he used to go. Hang out with a bunch of other grown men and look at trains. Then go to the pub and talk about trains. He had train sets at home – kids’ toys, though I was never allowed to touch them. He pored over those notebooks of his: stations, engine numbers, timetables. I never understood it. Still don’t.’

Birch wrinkled her nose. She didn’t buy this, entirely. In her experience, men didn’t disappear for days at a time solely because of a hobby. That might be the excuse they gave, but there had to be more to it. Bennet was a kid at the time, and likely to swallow whatever line he was fed.

‘Do you think there might have been anything else keeping your father away from home?’

Bennet sighed. ‘My mother was certain there was another woman, other women, whatever. I don’t think either of us ever saw any evidence of it. She just couldn’t believe he was that fanatical about trains.’

Her and me both, Birch thought.

‘Honestly? Maybe there was other stuff. Women, drink, whatever. But whenever my mother confronted him, she’d get back-handed. Meant she stopped asking where he’d been, pretty quick.’

Beside her, Birch could feel Amy’s resentment towards Bennet’s father glowing, like the heat of a small flame.

‘He always came back, though. It sounds twisted, but I believe he loved my mother more than anything. He was a little obsessed with her, in fact. He’d buy her red roses, treat her like porcelain, especially after . . . they’d fought. He called her his princess. That’s what makes it hard for me to believe there were other women. He loved her so much, in spite of everything.’

You don’t hit someone you love, Birch thought. But Bennet’s father did sound fairly textbook. Domestic abusers often showered their victims with adoration, especially in the wake of an attack.

Across the table, Bennet was musing. ‘I believe,’ he said, ‘that the reason we never got on, my old man and me, was ’cause he was jealous of me. I came along and took her away from him. Took up so much of her attention. He wasn’t the apple of her eye any more.’

Of course, Birch thought. Bennet lived in America: he’d have been to therapy. He had it all figured out. But how could he have left, when he knew his mother was at risk from this man?

‘He wasn’t unusual, you know.’ Bennet had seen what she was thinking. ‘Most of the kids I hung out with, their dads were like him. Bitter. Sometimes violent. Liked to keep to themselves and not be questioned. It was just how men were. Part of the reason I left was, I could see myself getting like that, getting like him, if I stayed working in dead-end jobs, giving up the dreams I had. He was normal, the default. I remember when I was maybe eight, our next-door neighbour had had enough and called the police, saying she’d heard a ruckus. My mother answered the door with a fresh black eye. The policeman said someone had complained about noise, and could you please keep it down in future, Mrs MacDonald? It was that normal of a thing. Expected, even.’

Birch winced. She gave thanks for the past five decades of progress in policing.

‘What did your father do for a living, Mr Bennet?’

Bennet grimaced. ‘Sanitary inspector,’ he said. ‘We did all right financ

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...