1

That night I dreamed that I was going back to the Cemetery of Forgotten Books. I was ten years old again, and again I woke up in my old bedroom feeling that the memory of my mother’s face had deserted me. And the way one knows things in a dream, I knew it was my fault and my fault only, for I didn’t deserve to remember her face because I hadn’t been capable of doing her justice.

Before long my father came in, alerted by my anguished cries. My father, who in my dream was still a young man and held all the answers in the world, wrapped me in his arms to comfort me. Later, when the first glimmer of dawn sketched a hazy Barcelona, we went down to the street. For some arcane reason he would only come with me as far as the front door. Once there, he let go of my hand, and I understood then that this was a journey I had to undertake on my own.

I set off, but as I walked I remember that my clothes, my shoes, and even my skin felt heavy. Every step I took required more effort than the previous one. When I reached the Ramblas, I noticed that the city had become frozen in a never-ending instant. Passersby had stopped in their tracks and appeared motionless, like figures in an old photograph. A pigeon taking flight left only the hint of a blurred outline as it flapped its wings. Motes of sparkling dust floated in the air like powdered light. The water of the Canaletas fountain glistened in the void, suspended like a necklace of glass tears.

Slowly, as if I were trying to advance underwater, I managed to press on across the spell of a Barcelona trapped in time, until I came to the threshold of the Cemetery of Forgotten Books. There I paused, exhausted. I couldn’t understand what invisible weight I was pulling behind me that barely allowed me to move. I grabbed the knocker and beat the door with it, but nobody came. I banged the large wooden door with my fists, again and again, but the keeper ignored my pleas. At last I fell on my knees, utterly spent. Then, as I gazed at the curse I had dragged behind me, it suddenly became clear to me that the city and my destiny would be forever caught in that haunting, and that I would never be able to remember my mother’s face.

* * *

It was only when I’d abandoned all hope that I discovered it. The piece of metal was hidden in the inside pocket of that school jacket with my initials embroidered in blue. A key. I wondered how long it had been there, unbeknown to me. It was rusty and felt as heavy as my conscience. Even with both hands, I could hardly lift it up into the keyhole. I struggled to turn it with my last bit of breath. But just as I thought I would never manage it, the lock yielded and slowly the large door slid open inward.

A curved gallery led into the old palace, studded with a trail of flickering candles that lit the way. I plunged into the dark and heard the door closing behind me. Then I recognized the corridor flanked by frescoes of angels and fabulous creatures: they peered at me from the shadows and seemed to move as I went past. I proceeded down the corridor until I reached an archway that opened out into a large hall with a vaulted ceiling. I stopped at the entrance. The labyrinth fanned out before me in an endless mirage. A spiral of staircases, tunnels, bridges, and arches woven together formed an eternal city made up of all the books in the world, swirling toward a grand glass dome high above.

My mother waited for me at the foot of the structure. She was lying in an open coffin, her hands crossed over her chest, her skin as pale as the white dress that covered her. Her lips were sealed, her eyes closed. She lay inert in the absent rest of lost souls. I moved my hand toward her to stroke her face. Her skin was as cold as marble. Then she opened her eyes and fixed them on me. When her darkened lips parted and she spoke, the sound of her voice was so thunderous it hit me like a cargo train, lifting me off the floor, throwing me into the air, and leaving me suspended in an endless fall while the echo of her words melted the world.

You must tell the truth, Daniel.

* * *

I woke up suddenly in the darkness of the bedroom, drenched in cold sweat, to find Bea’s body lying next to me. She hugged me and stroked my face.

“Again?” she murmured.

I nodded and took a deep breath.

“You were talking. In your dream.”

“What did I say?”

“I couldn’t make it out,” Bea lied.

I looked at her and she smiled at me with pity, I thought, or maybe it was just patience.

“Sleep a little longer. The alarm clock won’t go off for another hour and a half, and today is Tuesday.”

Tuesday meant that it was my turn to take Julián to school. I closed my eyes, pretending to fall asleep. When I opened them again a couple of minutes later, I found my wife’s face observing me.

“What?” I asked.

Bea leaned over and kissed me gently on my lips. She tasted of cinnamon. “I’m not sleepy either,” she hinted.

I started to undress her unhurriedly. I was about to pull off the sheets and throw them on the floor when I heard the patter of footsteps behind the bedroom door.

Bea held back the advance of my left hand between her thighs and propped herself up on her elbows.

“What’s the matter, sweetheart?”

Standing in the doorway, little Julián looked at us with a touch of shyness and unease. “There’s someone in my room,” he whispered.

Bea let out a sigh and reached out toward Julián. He ran over to take shelter in his mother’s embrace, and I abandoned all sinful expectations.

“The Scarlet Prince?” asked Bea.

Julián nodded shyly.

“Daddy will go to your room right now and give him such a kicking he’ll never come back again.”

Our son threw me a desperate look. What use is a father if not for heroic missions of this caliber?

I smiled at him and winked. “A major kicking,” I repeated, looking as furious as I could.

Julián allowed himself just a flicker of a smile. I jumped out of bed and walked along the corridor to his bedroom. The room reminded me so much of the one I had at his age, a few floors farther down, that for a moment I wondered if I wasn’t still trapped in my dream. I sat on one side of his bed and switched on the bedside table lamp. Julián lived surrounded by toys, some of which he’d inherited from me, but especially by books. It didn’t take me long to find the culprit, hidden under the mattress. I took that little book with black covers and opened to its first page.

I no longer knew where to hide those books. However much I sharpened my wits to find new hiding places, my son managed to sniff them out. Leafing quickly through the pages, I was assailed by memories.

When I returned to our bedroom, having banished the book once more to the top of the kitchen cupboard—where I knew my son would discover it sooner rather than later—I found Julián in his mother’s arms. They had both fallen asleep. I paused in the half-light to watch them from the open door. As I listened to their deep breathing, I asked myself what the most fortunate man in the world had done to deserve his luck. I gazed at them as they slept in each other’s arms, oblivious to the world, and couldn’t help remembering the fear I’d felt the first time I saw them clasped in an embrace.

2

I’ve never told anyone, but the night my son Julián was born and I saw him in his mother’s arms for the first time, enjoying the blessed calm of those who are not yet aware what kind of place they’ve arrived at, I felt like running away and not stopping until there was no more world left to run from. At the time I was just a kid and life was still a few sizes too big for me, but however many flimsy excuses I try to conjure up, I still carry the bitter taste of shame at the cowardice that possessed me then—a cowardice that, even after all those years, I have not found the courage to admit to the person who most deserved to know.

* * *

The memories we bury under mountains of silence are the ones that never stop haunting us. Mine take me back to a room with an infinitely high ceiling from which a lamp spread its faint ocher-colored light over a bed. There lay a girl, still in her teens, holding a baby in her arms. When Bea, vaguely conscious, looked up and smiled at me, my eyes filled with tears. I knelt by the bed and buried my head in her lap. I felt her holding my hand and pressing it with what little strength she had left.

“Don’t be afraid,” she whispered.

But I was. And for a moment whose shame has pursued me ever since, I wanted to be anywhere except in that room and in my own skin. Fermín had witnessed the scene from the door and, as usual, had read my thoughts even before I was able to articulate them. Without granting me a second to open my big mouth, he pulled my arm and, leaving Bea and the baby in the safe company of his fiancée, Bernarda, led me out to the hallway, a long angular corridor that melted into the shadows.

“Still alive in there, Daniel?” he asked.

I nodded vaguely as I tried to catch the breath I seemed to have dropped along the way. When I turned to go back into the room, Fermín restrained me.

“Listen, next time you show your face in there, you could use a bit more composure. Luckily Señora Bea is still half knocked out and almost certainly missed much of the dress rehearsal. If I may make a constructive suggestion, I think a blast of fresh air would do wonders. It would help us get over the shock and allow us to attempt a second landing with a bit more flair.”

Without waiting for an answer, Fermín grabbed my arm and escorted me down the long passageway. We soon reached a staircase that led to a balustrade suspended somewhere between Barcelona and the heavens. A cold, biting breeze caressed my face.

“Close your eyes and take three deep breaths,” Fermín advised. “Slowly, as if your lungs reached down to your shoes. It’s a trick I learned from a Tibetan monk I met during a brief but educational stint as receptionist-slash-accountant in a little port-side brothel. The rascal knew his business . . .”

As instructed, I inhaled three times as deeply as I could, and another three for good measure, taking in the benefits of the pure air promised by Fermín and his Tibetan guru. My head felt a bit giddy, but Fermín steadied me.

“Mind you don’t go catatonic on me, now,” he said. “Just smarten up a bit. The situation calls for temperance, not petrifaction.”

I opened my eyes to the sight of deserted streets and the city asleep at my feet. It was around three in the morning, and the Hospital de San Pablo was sunk in a shadowy slumber, its citadel of domes, towers, and arches weaving arabesques through the mist that glided down from the top of Mount Carmelo. I gazed silently at that indifferent Barcelona that can only be seen from hospitals, a city oblivious to the fears and hopes of the beholder, and I let the cold seep in until it cleared my mind.

“You must think me a coward,” I said.

Fermín held my gaze and shrugged.“Don’t overplay it. What I think is that you’re a bit low on blood pressure and a bit high on stage panic—which excuses you from responsibility and mockery. Luckily, a solution is at hand.”

He unbuttoned his raincoat, a vast emporium of wonders that doubled as a mobile herbalist’s shop, museum of odds and ends, and carrier bag of curiosities and relics picked up from a thousand flea markets and third-rate auctions.

“I don’t know how you can carry all those trinkets around with you, Fermín.”

“Advanced physics. Since my slender yet toned physique consists mostly of muscular fibers and lean cartilage, this cargo reinforces my gravitational field and provides firm anchoring against forces of nature. And don’t imagine you’re going to distract me that easily with comments that piddle outside the bucket. We haven’t come up here to swap stickers or to whisper sweet nothings.”

After that bit of advice, Fermín pulled out a tin flask from one of his countless pockets and began unscrewing the top. He sniffed the contents as if he were taking in the perfumes of paradise and smiled approvingly. Then he handed me the bottle and, looking solemnly into my eyes, gave me a nod. “Drink now or repent in the afterlife.”

I accepted the flask reluctantly. “What’s this? It smells like dynamite.”

“Nonsense. It’s just a cocktail designed to bring the dead back to life—as well as young boys who feel intimidated by life’s responsibilities. A secret master formula of my own invention, made with firewater and aniseed shaken together with a feisty brandy I buy from the one-eyed gypsy who peddles vaguely legal spirits. The mixture is rounded off with a few drops of Ratafia and Aromas de Montserrat liqueurs for that unmistakable Catalan bouquet.”

“God almighty.”

“Come on, this is where you tell the men from the boys. Down the hatch in one gulp, like a legionnaire who crashes a wedding banquet.”

I obeyed and swallowed the concoction. It tasted like gasoline spiked with sugar. The liquor set my insides on fire, and before I could recover Fermín indicated that I should repeat the operation. Objections and intestinal earthquake aside, I downed the second dose, grateful for the drowsy calm the foul drink had conferred on me.

“How’s that?” Fermín asked. “Better now? Truly the elixir of champions, eh?”

I nodded with conviction, gasping and loosening my neck buttons.

Fermín took the opportunity to take a gulp of his gunge, then put the flask back into his raincoat pocket. “Nothing like recreational chemistry to master the emotions. But don’t get too fond of the trick. Liquor is like rat poison or generosity—the more you make use of it, the less effective it becomes.”

“Don’t worry.”

Fermín pointed to a pair of Cuban cigars that peeped out of another of his raincoat pockets, but he shook his head and winked at me. “I had kept aside these two Cohibas, stolen on impulse from the humidifier of my future honorary father-in-law, Don Gustavo Barceló, but we’d better keep them for another day. You’re not in the best of shape, and it would be most unwise to leave the little babe fatherless on his opening day.”

Fermín gave me a friendly slap on the back and let a few seconds go by, allowing time for the fumes of his cocktail to spread through my veins and a mist of drunken sobriety mask the silent panic that had seized me. As soon as he noticed the glazed look in my eyes and the dilated pupils that announced the general stupefaction of my senses, he threw himself into the speech he’d probably been dreaming up all night long.

“Daniel, my friend. God, or whoever fills in during his absence, has seen fit to make it easier to become a father than to pass one’s driving test. Such an unhappy circumstance means that a disproportionate legion of cretins, dimwits, and bona fide imbeciles flaunt paternity medals and consider themselves fully qualified to keep procreating and ruining forever the lives of the unfortunate children they spawn like mice. That is why, speaking with the authority bestowed on me by the fact that I too find myself ready to embark on the enterprise of getting my beloved Bernarda knocked up as soon as possible, once my gonads and the holy matrimony certification she is demanding sine qua non allow me—so that I may follow you in this journey of great responsibility that is fatherhood—I must declare, and I do declare that you, Daniel Sempere Gispert, tender youngster on the verge of maturity, despite the thin faith you feel at this moment in yourself and in your feasibility as a paterfamilias, are and will be an exemplary father, even if, generally speaking, sometimes you seem born the day before yesterday and wetter behind the ears than a babe in the woods.”

By the middle of his oration my mind had already drawn a blank, either as a result of the explosive concoction or thanks to the verbal fireworks set off by my good friend. “Fermín,” I said, “I’m not sure I grasp your meaning.”

Fermín sighed. “What I meant, Daniel, was that I’m aware that right now you feel you’re about to soil your undies and that all this is overwhelming, but as your saintly wife has informed you, you must not be afraid. Children, at least yours, Daniel, bring joy and a plan with them when they’re born, and so long as one has a drop of decency in one’s soul, and some brains in one’s head, one can find a way to avoid ruining their lives and be a parent they will never have to be ashamed of.”

I looked out of the corner of my eye at that little man who would have given his life for me and who always had a word, or ten thousand, with which to solve my every problem and my occasional lapses into a state of spiritual indecision. “Let’s hope it’s as easy as you describe it, Fermín.”

“In life, nothing worthwhile is easy, Daniel. When I was young I thought that in order to sail through the world you only needed to do three things well. First, tie your shoelaces properly. Second: undress a woman conscientiously. And third: read a few pages for pleasure every day, pages written with inspiration and skill. I thought that a man who has a steady step, knows how to caress, and learns how to listen to the music of words will live longer and, above all, better. But time has shown me that this isn’t enough, and that sometimes life offers us an opportunity to aspire to be more than a hairy bipedal creature that eats, excretes, and occupies a temporary space in the planet. And so it is today that destiny, with its boundless lack of concern, has decided to offer you that opportunity.”

I nodded, unconvinced. “What if I don’t make the grade?”

“If there’s one thing we have in common, Daniel, it’s that we’ve both been blessed with the good fortune of finding women we don’t deserve. It is clear as day that in this journey they are the ones who will decide what baggage we’ll need and what heights we’ll attain, and all we have to do is try not to fail them. What do you say?”

“That I’d love to believe you wholeheartedly, but I find it hard.”

Fermín shook his head, as if to make light of the matter. “Don’t worry. The mixture of spirits I’ve poured down you is clouding what little aptitude you have for my refined rhetoric. But you know that in these matters I have a lot more miles on the clock than you, and I’m normally as right as a truckload of saints.”

“I won’t argue that point.”

“And you’ll do well not to, because you’d be knocked out in the first round. Do you trust me?”

“Of course I do, Fermín. I’d go with you to the end of the world, you know that.”

“Then take my word for it and trust yourself as well. The way I do.”

I looked straight into his eyes and nodded slowly.

“Recovered your common sense?” he asked.

“I think so.”

“In that case wipe away that doleful expression, make sure your testicular mass is safely stored in the proper location, and go back to the room to give Señora Bea and the baby a hug, like the man they’ve just made you. Make no mistake about it: the boy I had the honor of meeting some years ago, one night beneath the arches of Plaza Real, the boy who since then has given me so many frights, must remain in the prelude of this adventure. We still have a lot of history to live through, Daniel, and what awaits us is no longer child’s play. Are you with me? To that end of the world, which, for all we know, might only be around the corner?”

I could think of nothing else to do but embrace him. “What would I do without you, Fermín?”

“You’d make a lot of mistakes, for one thing. And while we’re on the subject of caution, bear in mind that one of the most common side effects derived from the intake of the concoction you have just imbibed is a temporary softening of restraint and a certain overexuberance on the sentimental front. So now, when Señora Bea sees you step into that room again, look straight into her eyes so that she realizes that you really love her.”

“She knows that already.”

Fermín shook his head patiently. “Do as I say,” he insisted. “You don’t have to tell her in so many words, if you feel embarrassed, because that’s what we men are like and testosterone doesn’t encourage eloquence. But make sure she feels it. These things should be proven rather than just said. And not once in a blue moon, but every single day.”

“I’ll try.”

“Do a bit more than try, Daniel.”

And so, stripped, thanks to Fermín’s words and deeds, of the eternal and fragile shelter of my adolescence, I made my way back to the room where destiny awaited.

* * *

Many years later, the memory of that night would return when, seeking a late-night refuge in the back room of the old bookshop on Calle Santa Ana, I tried once more to confront a blank page, without even knowing how to begin to tell myself the real story of my family. It was a task to which I had devoted months or even years, and to which I had been incapable of contributing a single line worth saving.

Making the most of a bout of insomnia, which he attributed to having eaten half a kilo of deep-fried pork rinds, Fermín had decided to pay me a visit in the wee hours. When he caught me agonizing in front of a blank page, armed with a fountain pen that leaked like an old car, he sat down beside me and checked the tide of crumpled folios spread at my feet. “Don’t be offended, Daniel, but have you the slightest idea of what you’re doing?”

“No,” I admitted. “Perhaps if I tried using a typewriter, everything would change. The advertisements say that Underwood is the professional’s choice.”

Fermín considered the publicity promise, but shook his head vigorously. “Typing and writing are different things, light-years apart.”

“Thanks for the encouragement. What about you? What are you doing here at this time of night?”

Fermín tapped his belly. “The consumption of an entire fried-up pig has left my stomach in turmoil.”

“Would you like some bicarbonate of soda?”

“No, I’d better not. It always gives me a monumental hard-on, if you’ll forgive me, and then I really can’t sleep a wink.”

I abandoned my pen and my umpteenth attempt at producing a single usable sentence, and searched my friend’s eyes.

“Everything all right here, Daniel? Apart from your unsuccessful storming of the literary castle, I mean . . .”

I shrugged hesitantly. As usual, Fermín had arrived at the providential moment, living up to his natural role of a roguish deus ex machina.

“I’m not sure how to ask you something I’ve been turning over in my mind for quite a while,” I ventured.

He covered his mouth with his hand and let go a short but effective burp. “If it’s related to some bedroom technicality, don’t be shy, just fire away. May I remind you that on such issues I’m as good as a qualified doctor.”

“No, it’s not a bedroom matter.”

“Pity, because I have fresh information on a couple of new tricks that—”

“Fermín,” I interrupted. “Do you think I’ve lived the life I was supposed to live, that I’ve not fallen short of expectations?”

My friend seemed lost for words. He looked down, sighing.

“Don’t tell me that’s what’s behind this bogged-down-Balzac phase of yours. Spiritual quest and all that . . .”

“Isn’t that why people write—to gain a better understanding of themselves and of the world?”

“No, not if they know what they’re doing, and you—”

“You’re a lousy confessor, Fermín. Give me a little help.”

“I thought you were trying to become a novelist, not a holy man.”

“Tell me the truth, Fermín. You’ve known me since I was a child. Have I disappointed you? Have I been the Daniel you hoped for? The one my mother would have wished me to be? Tell me the truth.”

Fermín rolled his eyes. “Truth is the rubbish people come up with when they think they know something, Daniel. I know as much about truth as I know about the bra size of that fantastic female with the pointy name and pointier bosom we saw in the Capitol Cinema the other day.”

“Kim Novak,” I specified.

“Whom may God and the laws of gravity hold forever in their glory. And no, you have not disappointed me, Daniel. Ever. You’re a good man and a good friend. And if you want my opinion, yes, your late mother, Isabella, would have been proud of you and would have thought you were a good son.”

“But not a good novelist.” I smiled.

“Look, Daniel, you’re as much a novelist as I’m a Dominican monk. And you know that. No pen or Underwood under the sun can change that.”

I sighed and fell into a deep silence. Fermín observed me thoughtfully.

“You know something, Daniel? What I really think is that after everything you and I have been through, I’m still that same poor devil you found lying in the street, the one you took home out of kindness, and you’re still that helpless, lost kid who wandered about stumbling on endless mysteries, believing that if you solved them, perhaps, by some miracle, you would recover your mother’s face and the memory of the truth that the world had stolen from you.”

I mulled over his words; they’d touched a nerve. “And if that were true, would it be so terrible?”

“It could be worse. You could be a novelist, like your friend Carax.”

“Perhaps what I should do is find him and persuade him to write the story,” I said. “Our story.”

“That’s what your son Julián says, sometimes.”

I looked at Fermín askance. “Julián says what? What does Julián know about Carax? Have you talked to my son about Carax?”

Fermín adopted his official sacrificial lamb expression. “Me?”

“What have you told him?”

Fermín puffed, as if making light of the matter. “Just bits and pieces. At the very most a few, utterly harmless footnotes. The trouble is that the child is inquisitive by nature, and he’s always got his headlights on, so of course he catches everything and ties up loose ends. It’s not my fault if the boy is smart. He obviously doesn’t take after you.”

“Dear God . . . and does Bea know you’ve been talking to the boy about Carax?”

“I don’t interfere in your marital life. But I doubt there’s much Señora Bea doesn’t know or guess.”

“I strictly forbid you to talk to my son about Carax, Fermín.”

He put his hand on his chest and nodded solemnly. “My lips are sealed. May the foulest ignominy fall upon me if in a moment of tribulation I should ever break this vow of silence.”

“And while we’re at it, don’t mention Kim Novak, either. I know you only too well.”

“On that matter I’m as innocent as the Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world: it’s the boy who brings up that subject, he’s not stupid by half.”

“You’re impossible.”

“I humbly accept your unfair remarks, because I know they’re provoked by the frustration of your own emaciated ingenuity. Does Your Excellency have any other names to add to the blacklist of unmentionables, apart from Carax? Bakunin? Mae West?”

“Why don’t you go off to bed and leave me in peace, Fermín?”

“And leave you on your own to face the danger? No way. There must at least be one sane and responsible adult among the audience.”

Fermín examined the fountain pen and the pile of blank pages waiting on the table, assessing them with fascination, as if he were looking at a set of surgical instruments. “Have you figured out how to get this enterprise up and running?”

“No. I was doing just that when you came in and started making obtuse remarks.”

“Nonsense. Without me you can’t even write a shopping list.”

Convinced at last, and rolling up his sleeves to face the titanic task before us, he sat himself down on a chair beside me, looking at me with the fixed intensity of someone who scarcely needs words to communicate.

“Speaking of lists: look, I know as much about this novel-writing business as I do about the manufacture and use of a hair shirt, but it occurs to me that before beginning to narrate anything, we should make a list of what we want to tell. An inventory, let’s say.”

“A road map?” I suggested.

“A road map is what people rough out when they’re not sure where they’re going, to convince themselves and some other simpleton that they’re going somewhere.”

“It’s not such a bad idea. Self-deceit is the key to all impossible ventures.”

“You see? Together we make an invincible duo. You take notes, and I think.”

“Then start thinking aloud.”

“Is there enough ink in that piece of junk for a round trip to hell and back?”

“Enough to start walking.”

“Now all we need to decide is where we begin the list.”

“What if we begin with the story of how you met her?” I asked.

“Met who?”

“Who do you think? Our Alice in the Wonderland of Barcelona.”

A shadow crossed his face. “I don’t think I’ve ever told anyone that story, Daniel. Not even you.”

“In that case, what better entrance could there be to the labyrinth?”

“A man should be allowed to take some secrets to his grave,” Fermín objected.

“Too many secrets may take that man to his grave before his time.”

Fermín raised his eyebrows in surprise. “Who said that? Socrates? Myself?”

“No. For once it was Daniel Sempere Gispert, the simpleton, only a few seconds ago.”

Fermín smiled with satisfaction, peeled a lemon Sugus, and put it in his mouth. “It’s taken you years, but you’re starting to learn from the master, you rascal. Would you like a Sugus?”

I accepted the piece of candy because I knew it was the most treasured possession in my friend Fermín’s estate, and he was honoring me by sharing it.

“Have you ever heard that much-abused saying that all’s fair in love and war, Daniel?”

“Sometimes. Usually by those who favor war rather than love.”

“That’s right, because when all’s said and done, it’s a rotten lie.”

“So, is this a story of love or war?”

Fermín shrugged. “What’s the difference?”

And so, under cover of midnight, a couple of Sugus, and the spell of memories that were threatening to disappear in the mist of time, Fermín began to connect the threads that would weave the end and the beginning of our story . . .

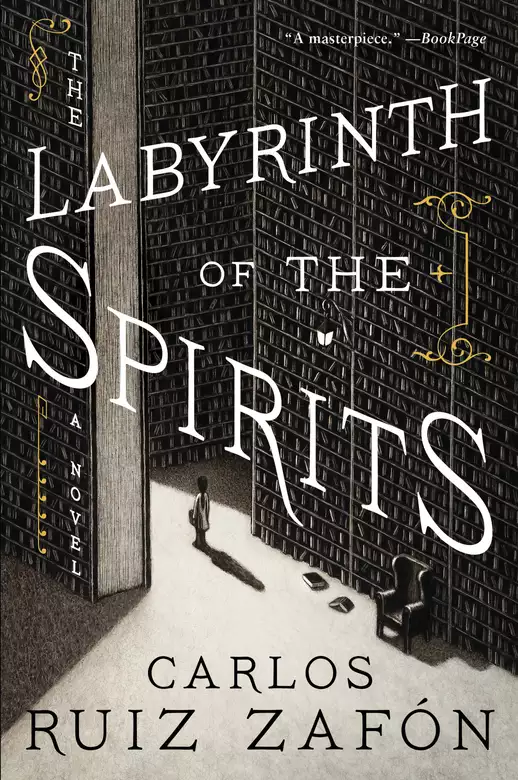

Excerpt from The Labyrinth of the Spirits (The Cemetery of Forgotten Books, volume IV), by Julián Carax. Edited by Émile de Rosiers Castellaine. Paris: Éditions de la Lumière, 1992.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved