- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Not Yet Available

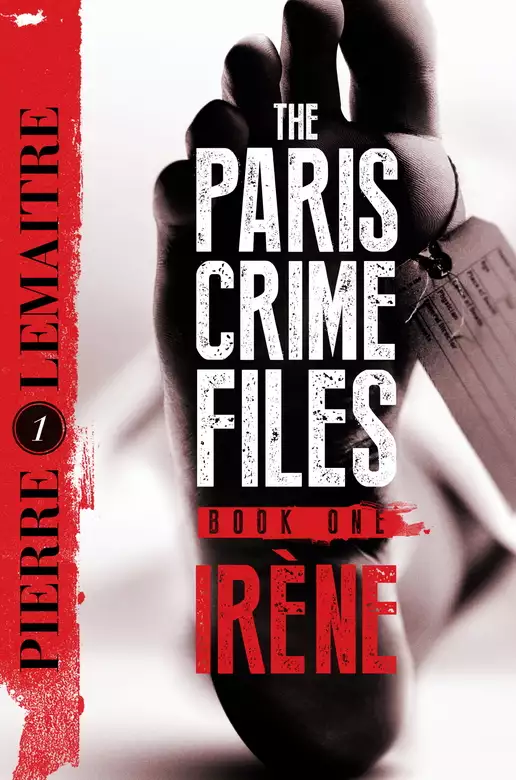

Release date: March 6, 2014

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

Irene

Pierre Lemaitre

“Alice …” he said, looking at what anyone else would have called a young girl.

He used her name as a sign of complicity but could not make the slightest dent in her armour. He looked down at the notes scribbled by Armand during the first interview: Alice Vandenbosch, 24. He tried to imagine what 24-year-old Alice Vandenbosch normally looked like. She was probably a young woman with a long, slim face, sandy hair, honest eyes. What he saw when he looked up seemed completely improbable. The girl was nothing like herself: her hair, once blonde, was plastered to her skull and dark at the roots; her face had a sickly pallor, a large purple bruise on her right cheek, thin threads of dried blood at one corner of her mouth … all that was human in her wild, frantic eyes was fear, a fear so terrible she was still shivering as though she had gone out on a winter’s day without a coat. She clutched the plastic coffee cup with both hands, like a lifeline.

Usually, when Camille Verhœven stepped into a room, even the coolest of customers reacted. Not Alice. Alice was shut away inside herself, trembling.

It was 8.30 a.m.

A few minutes earlier, when he had arrived at the brigade criminelle, Camille had felt tired. Dinner the night before had gone on until 1 a.m. People he did not know, friends of Irène. They had talked about television, told stories that Camille might have found quite funny, but for the fact that he was sitting opposite a woman who reminded him of his mother. All through the meal he had tried to dispel the image, but it was uncanny: the same stare, the same mouth, the same cigarettes smoked one after the other. Camille had found himself swept back twenty years to a blessed time when his mother would emerge from her studio wearing a smock smeared with paint, a cigarette dangling from her lips, her hair dishevelled. A time when he would still go to watch her work. She was an Amazon. Solid and focused, with a furious brushstroke. She lived so much inside her head that sometimes she did not seem to notice his presence. Long, silent periods back when he had loved painting, back when he watched her every movement as though it might be the key to some mystery that concerned him personally. That was before. Before the serried ranks of cigarettes declared open war on her, but long after they caused the foetal hypotrophy that marked Camille’s birth. At the time, drawing himself up to his full height – he would never be taller than four foot eleven – Camille did not know which he hated more, the mother whose toxic habit had fashioned him into a kind of pale, slightly less deformed copy of Toulouse-Lautrec, or the meek, powerless father who gazed at his wife with pathetic admiration, as though at his own reflection in a mirror: at sixteen he was already a man, though not in stature. While his mother accumulated canvases in her studio and his laconic father worked at the pharmacy, Camille learned what it meant to be short. As he grew older, he stopped desperately trying to stand on tiptoe, got used to looking at others from below, gave up trying to reach shelves without fetching a stool, laid out his personal space like a doll’s house. And this diminutive man would survey, without really understanding, the vast canvases his mother had to roll up in order to take them to gallery owners. Sometimes his mother would say, “Camille, come here a minute …” Sitting on a stool, she would silently run her fingers through his hair and Camille knew that he loved her; at times he thought he would never love anyone else.

Those were the good times, Camille thought over dinner as he stared at the woman sitting opposite who laughed raucously, drank little and smoked like a chimney. The time before his mother spent her days kneeling next to her bed, resting her cheek on the blankets, the only position in which the cancer gave her a little respite. Illness had brought her to her knees. And though by now each found the other unfathomable, this was the first time that they could look at each other eye to eye. At the time, Camille had sketched a lot, spending long hours in his mother’s now deserted studio. When he decided to go into her room he would find his father, who now also spent half his life on his knees, pressed against his wife, his arm around her shoulders, saying nothing, breathing to the same rhythm as her. Camille was left alone. Camille sketched. Camille killed time and he waited.

By the time he went to law school, his mother weighed as little as one of her paintbrushes. Whenever he came home, his father seemed cloaked in a heavy silence of grief. The whole thing dragged on. And Camille bent his permanently childlike body over his law books and waited for it to end.

It arrived on a May day like any other. The telephone call might almost have been from a stranger. His father said simply, “You should probably come home.” And he knew straight away that from then on he would have to make his own way in the world, that there would never be anyone else.

At forty, this short, bald man with his long, furrowed face knew that this was not true, now that Irène had come into his life. But all these visions from the past had made for an exhausting evening. Besides, game had never really agreed with him.

It was at about the time he was bringing Irène her breakfast on a tray that Alice had been picked up by a squad car on the boulevard Bonne-Nouvelle.

“In ten minutes,” said Camille, “I want you to come and tell me you’ve found Marco. And that he’s in a bad way.”

“Found Marco …?” Armand was puzzled. “Where?”

“What the fuck do I know, just make it happen.”

With short, swift strides, Camille scuttered back to his office.

“So,” he said as he came towards Alice, “Let’s take it again from the beginning.”

He stood facing her, they were almost eye to eye. Alice seemed to wake from her trance. She stared at him as though seeing him for the first time and must have felt more keenly than ever how ridiculous the world was; two hours earlier she had been beaten up, her body was a mass of bruises, now here she sat in the brigade criminelle staring at a man no more than four foot eleven tall who was suggesting they start again from the beginning, as though this nightmare had a beginning.

Camille sat at his desk and automatically picked a pencil from among the dozen or so in the cut-glass desk tidy Irène had given him. He looked at Alice. She was not an ugly girl, rather pretty, in fact. Her delicate, sorrowful features were somewhat gaunt from too many late nights and too little care. A pietà. She looked like a reproduction of a classical statue.

“How long have you been working for Santeny?” he asked, sketching the curve of her face with a single stroke.

“I don’t work for him!”

“O.K., let’s say two years then. So you work for him and he supplies you, is that the deal?”

“No.”

“And you still think he’s in love with you, am I right?”

She glared at him. Camille smiled and looked down at his drawing. There was a long silence. Camille remembered a favourite phrase of his mother’s: “It’s the artist’s heart that beats inside the model’s body.”

On the sketchpad, with a few deft strokes, a different Alice slowly began to appear, younger than the woman sitting opposite, just as sorrowful but not as bruised. Camille looked at her again and seemed to come to a decision. Alice watched as he pulled a chair up next to her and perched on it like a child, his feet dangling.

“Mind if I smoke?” Alice said.

“Santeny’s in deep, deep shit,” Camille said as though he hadn’t heard. “The world and his brother are gunning for him. But you know that better than anyone, don’t you?” he said, gesturing to her bruises. “Not exactly friendly, are they? So it’s probably best that we find him first, don’t you think?”

Alice seemed to be hypnotised by Camille’s shoes, which swung like a two pendulums several inches from the floor.

“He’s got no-one to turn to, no way out of this. I give him a couple of days at most. But then you haven’t got anyone either, have you? They’ll track you down … Now, where’s Santeny?”

A stubborn little pout, like a child who knows she’s doing something wrong but does it anyway.

‘O.K., never mind … you’re free to go,” said Camille, as though talking to himself. “Next time I see you, I hope it’s not at the bottom of a rubbish skip.”

At precisely that moment Armand stepped into the office.

“We’ve just found Marco. You were right, he’s in a terrible way.”

Camille looked at Armand in feigned surprise.

“Where was he?”

“His place.

Camille shot his colleague a pitiful look: even with his imagination Armand was tight-fisted.

“O.K. Anyway, we can let the girl go,” he said, hopping down from the chair.

A little flurry of panic, then:

“He’s in Rambouiller,” muttered Alice under her breath.

“Oh,” said Camille, unimpressed.

“Boulevard Delagrange, number 18.”

“Eighteen,” Camille echoed, as though repeating the number excused him from having to thank the young woman.

Without waiting for permission, Alice took a crumpled cigarette pack from her pocket and lit one.

“Those things will kill you,” Camille said.

Camille was gesturing to Armand to dispatch a squad to the address when the telephone rang. On the other end, Louis sounded out of breath.

“We’ve got a clusterfuck out in Courbevoie,” he panted.

“Do tell …” Camille said laconically, picking up a pen.

“We received an anonymous tip-off this morning. I’m there right now. It’s … I don’t know how to describe it—”

“Why don’t you give it a go,” Camille interrupted fractiously, “see what we come up with.”

“It’s carnage,” Louis said in a strangulated voice, struggling to find the words. “It’s a bloodbath. But not the usual kind, if you see what I mean …”

“I don’t see, Louis, not really.”

“It’s like nothing I’ve ever seen in my life …”

Since his extension was engaged, Camille walked to Commissaire Le Guen’s office. He knocked curtly but did not wait for an answer. He liked to make an entrance.

Le Guen was a big man who had spent more than twenty years following one diet after another without losing a single gram. He had acquired a somewhat weary fatalism which was visible in his face, in his whole body. Camille had noticed that, over the years, he had adopted the air of a deposed king, surveying the world with a sullen, disillusioned expression. Hardly had Camille said a word than Le Guen interrupted him purely on principle, explaining that, whatever it was, “he didn’t have the time”. But when he saw the slim dossier Camille had brought, he decided accompany him to the crime scene nonetheless.

On the telephone Louis had said, “It’s like nothing I’ve ever seen in my life …” This worried Camille; his assistant was not given to doom-mongering. In fact he was exasperatingly optimistic, so Camille expected nothing good of this unexpected call-out. As the Péripherique flashed past, Camille Verhœven could not help but smile thinking about Louis.

Louis was blond, his hair parted to the side, and he had that unruly tuft genetically bestowed upon children of the privileged classes, a wayward curl constantly flicked back with a jerk of the head or a nonchalant yet practised hand. Over time, Camille had learned to distinguish the different messages conveyed by the way he pushed back his hair, a veritable barometer for gauging Louis’ moods. The right-handed variant covered a range of meanings running from “Let’s be reasonable” to “That’s simply not done”. The left-handed variant signalled embarrassment, awkwardness, timidity or confusion. Looking at Louis, it was easy to imagine him as an altar boy. He still had the youthful looks, the grace, the fragility. In short, Louis was elegant, slim, delicate, and a royal pain in the arse.

To crown it all, Louis was loaded. He had all the trappings of the filthy rich: a certain way of deporting himself, a particular way of speaking, of articulating, of choosing his words, everything in fact that comes from the top-shelf mould marked “Rich spoiled brat”. Louis had initially excelled at university (where he had studied a little law, some economics, history of art, aesthetics, psychology), changing courses according to his whims, unfailingly brilliant, treating education as a series of inane achievements. And then something had happened. From what Camille understood, it had to do with Descartes’ dark night of the soul and the demon drink – a combination of philosophical intuition and single malt whisky. Louis had seen his life stretching out before him, in his perfectly appointed six-room apartment lined with bookshelves full of tomes on art and inlaid cabinets filled with designer crockery, the rents from his various properties rolling in like a civil servant’s salary, spending holidays at his mother’s place in Vichy, frequenting the same neighbourhood restaurants, and he found himself confronted by a personal paradox as sudden as it was strange, a genuine existential crisis which anyone other than Louis would have summed up by saying “What the fuck am I doing here?”

Camille was convinced that, had he been born thirty years earlier, Louis would have become a left-wing revolutionary, but these days ideology no longer offered an alternative. Louis despised sanctimoniousness, and by extension voluntary work and charity. He needed to find something to do with his life, his own living hell. And suddenly it became clear to him: he would join the police. Louis never doubted for a moment that he would be accepted into the brigade criminelle – doubt was not a family trait, and Louis’ brilliance meant that he was rarely disillusioned. He passed his police exams and joined the force, motivated partly by a desire to serve (not to Protect and Serve, but simply to serve a purpose), partly by the fear that life would soon become entirely solipsistic and partly, perhaps, out of an imagined debt he felt he owed the working classes for not having been born one of their number. When he passed his detective’s exams, Louis found the world utterly different from how he had imagined it: it had nothing of the quaintness of Agatha Christie or the deductive logic of Conan Doyle; instead Louis found himself faced with filthy hovels and battered wives, drug dealers bleeding to death in rubbish skips in Barbès, knife fights between junkies, putrid toilets where the addicts who survived the fights O.D.’d, rent-boys selling their arses for a line of coke and johns who refused to pay more than €5 for a blowjob after 2 a.m. In the early days, Camille found it entertaining to observe Louis, the blond fringe, the florid vocabulary, his eyes filled with horror but his mind like a steel trap, as he filled out endless reports; Louis imperturbably taking witness statements in echoing, piss-stained stairwells next to the corpse of some thirteen-year-old pimp who had been hacked to death with a machete in front of his mother; Louis heading home at two in the morning to his enormous apartment on the rue Notre-Dame-de-Lorette and collapsing fully dressed on his velvet sofa beneath an engraving by Pavel, between the bookcase of signed first editions and his late father’s collection of amethysts.

When Louis first arrived at the brigade criminelle, the commandant did not immediately take to this smooth, clean-cut young man with the upper-class drawl who seemed unfazed by everything. The other officers on the team, who found it mildly entertaining to spend their days with a golden boy, were ruthless. Within less than two months, Louis had encountered most of the cruel pranks and hazing rituals with which groups humiliate outsiders. Louis accepted his fate without complaint, smiling awkwardly.

Camille noticed earlier than his colleagues that this surprising and intelligent young man had the makings of a good officer but, perhaps trusting to Darwinian selection, he decided not to intervene. Louis, with his rather British stiff upper lip, was grateful to him for that. One evening, as he was leaving the offices, Camille saw Louis dash to the bar across the road and knock back two or three shots. It reminded him of the fight scene in “Cool Hand Luke” where Paul Newman, battered, dazed and unable to land a punch, keeps getting up every time he’s knocked down until the men watching lose heart, even his opponent loses the will to fight. And indeed, faced with Louis’ professional diligence and his surprising ability to appeal to their better nature, the other officers eventually gave up. Over the years, Camille and Louis accepted each other’s differences, and since the commandant enjoyed an undisputed moral authority over the team, no-one was surprised that the rich kid gradually became his closest colleague. Camille always addressed Louis by his first name, as he did everyone on his team. But as time passed and the team changed, he realised that only the longest-serving members called him Camille. These days the team was mostly comprised of rookies, and Camille sometimes felt as though he had usurped a role he had never sought and become patriarch. The rookies addressed him as “commandant”, though he knew this was less to do with hierarchy than an attempt to compensate for the instinctive embarrassment they felt at his diminutive stature. Louis also addressed him by his surname, but Camille knew that his motivation was different: it was a reflex of his class. The two men had never quite become friends, but they respected one another, and both felt that this was a better basis for a good working relationship.

Camille and Armand, with Le Guen trailing behind, arrived at 17, rue Félix-Faure in Courbevoie shortly after 10 a.m. It was an industrial wasteland.

In its centre a small derelict factory lay like a dead insect, surrounded by former workshops that were currently being renovated. The four finished units looked as out of place as Tiki huts in a snowy landscape. All had white rendering, glass roofs, and aluminium windows with sliding panels, offering a glimpse of their vast interiors. The whole place looked deserted. There were no cars save those of the brigade criminelle.

Two steps led up to the warehouse apartment. From behind, Camille saw Louis leaning against a wall, spitting into a plastic bag he kept pressed to his mouth. Camille walked past, followed by Le Guen and two other officers from the team, and stepped into a room lit by the blinding glare of spotlights. When they arrive at a crime scene, rookie officers unconsciously look around for death. Experienced officers look for life. But there was no life here; death had leached into every space, even the bewildered eyes of the living. Camille had no time to worry about the strange atmosphere that pervaded the room as his gaze was immediately arrested by the head of a woman nailed to the wall.

Hardly had he taken three paces into the room than he found himself faced with a scene he could not have imagined even in his worst nightmares: severed fingers, torrents of clotted blood, the stench of excrement and gutted entrails. Instinctively, he was reminded of Goya’s painting, “Saturn Devouring His Son”, and for an instant he could see the terrifying face, the bulging eyes, the crimson mouth, the utter madness. Though he was one of the most experienced officers on the scene, Camille felt the urge to turn back to the doorway where Louis, not meeting anyone’s eye, held his plastic bag at arm’s length, like a beggar declaring his contempt for the world.

“What the fuck is this …?” Commissaire Le Guen muttered to himself, and his words were swallowed by the void. Only Louis heard him and came over, wiping his eyes.

“I don’t know,” he said. “I walked in and had to walk straight back out again … That’s as far as I’ve got.”

Standing in the middle of the room, Armand turned towards the two men, looking dazed. He wiped his clammy hands on his trousers and tried to compose himself.

Bergeret, head of the forensics team from identité judiciaire, went over to Le Guen.

“I’m going to need two teams. This is going to take a while.” Then, with uncharacteristic candour, he added: “It’s not exactly your usual crime scene.”

There was nothing usual about it at all.

“O.K., I’ll leave you to it,” Le Guen said to Maleval, who had just come into the room and was already racing out, both hands clasped over his mouth.

Camille signalled to his team that it was time to man up.

*

It was impossible to imagine what the apartment had looked like before … this. Because “this” had now ravaged the place and they did not know which way to turn. To Camille’s right, sprawled on the ground, were the remains of a disembowelled body, jagged, broken ribs poking through the stomach, and one breast, the other having been hacked off, but it was difficult to say for sure since the body of the woman – that it was a woman was the only thing that seemed certain – was smeared with excrement which only partially covered countless bitemarks. To the left was a head, the eyes burned out. From the gaping mouth snaked pink and white veins. Opposite lay a body from which the skin had been partially peeled away, deep gashes lacerated the flesh and there were yawning wounds, carefully demarcated openings in the belly and vagina, probably made using acid. The head of the second victim had been nailed to the wall through the cheeks. Camille surveyed the scene, and took a notebook from his pocket, only to quickly put it back again as though acknowledging that the task was so monstrous that all his methods were useless, every approach doomed to failure. There is no strategy for dealing with atrocity. And yet this was why he was here, staring at the nameless horror.

Before it had clotted, someone had used the victims’ blood to daub on the wall in huge letters: I AM BACK. It was obvious from the long drips at their base that a lot of blood had been used. The characters had been scrawled using several fingers, sometimes together, sometimes apart, so that the inscription seemed somehow blurred. Camille stepped over the mangled body of a woman and went to the wall. At the end of the sentence, a finger had been pressed against the plaster with great care. Every ridge and whorl was distinct; it looked just like the old-style I.D. cards when a duty officer would press your finger against the yellowing cardboard, rolling it carefully from one side to the other.

Dark sprays of blood spattered the walls all the way to the ceiling.

It took several minutes for Camille to compose himself. It would be impossible for him to think rationally in this setting – everything he could see defied reason.

*

There were about a dozen people now working in the apartment. As in an operating theatre, to outsiders the atmosphere at a crime scene can often seem quite relaxed. People are quick to laugh and joke. It was something Camille loathed. Conversation between S.O.C.O.s was full of crude jokes and sexual innuendo, as though they needed to prove they were blasé. A common attitude in professions that are predominantly male. To a forensics officer accustomed to dissociating horror from reality, the body of a woman – even when dead – is still a woman’s body, a female suicide victim can still be described as “a good-looking woman” even when her face has bloated and turned blue. But the atmosphere in the apartment in Courbevoie was very different. It was neither grieving nor compassionate, but hushed and powerful, as though even the most hard-bitten officers, caught off guard, were wondering how they could possibly make light of a body that had been disembowelled beneath the sightless gaze of a head nailed to the wall. And so, in silence, the forensics team took measurements, collected samples, redirected the spotlights as they snapped photographs, documenting the scene with an almost religious stillness. Though Armand was an experienced officer, his face was deathly pale as he stepped over the crime-scene tape with a ritualised slowness, as though fearing that a sudden movement might rouse the furies that still haunted this place. As for Maleval, he was still puking his guts out into a plastic bag; he had twice tried to join his team only to immediately back away, literally suffocated by the stench of excrement and rotting flesh.

*

The apartment was huge. Despite the mess, it was clear that great care had been taken in decorating it. As in most warehouse apartments of its kind, the front door opened directly onto the living room, a vast space with whitewashed concrete walls. The right-hand wall was filled by an enormous print. You had to step back to get a sense of it. It was an image Camille felt he had seen before. Standing in the doorway, he racked his brains, trying to remember.

“The human genome,” Louis said.

That was what it was: a reproduction of the human genome reworked by an artist in ink and charcoal.

A large picture window looked out onto a development of semi-detached houses in the distance, screened by trees that had not yet had time to grow. A faux cowhide was tacked to one wall, a long rectangular piece of leather daubed with distinctive black and white markings. Beneath it was a black leather sofa of astonishing proportions, probably a bespoke piece of furniture custom-made to the precise dimensions of the wall, but it was impossible to know – this was not a home but a different world, one where people hung giant pictures of the human genome on the wall and hacked young women to pieces after first eviscerating them … Lying on the floor beside the sofa was an issue of GQ magazine. To the right was a well-stocked bar and to the left a coffee table with a cordless phone and an answering machine. Nearby, on a smoked-glass cabinet, was a large flat-screen television.

Armand was kneeling in front of the unit. Camille, who given his height was usually in no position to do so, laid a hand on his shoulder and, gesturing to the V.C.R., said, “Let’s have a look at what’s in there.”

The cassette was rewound. The video showed a dog – a German shepherd wearing a baseball cap – peeling an orange gripped between its front paws and eating the segments. It looked like something from one of those T.V. shows of “hilarious” home videos, the filming amateurish, the framing predictable and crude. In the bottom right-hand corner was a logo for “U.S.-Gag” featuring a smiling cartoon camera.

“Let it run,” Camille said. “You never know.”

He bent over the answering machine. The music on the outgoing message seemed to have been dictated by the zeitgeist. A few years ago, it would have been Pachelbel’s “Canon”. Camille thought he recognised “Spring” from Vivaldi’s “Four Seasons”.

“‘Autumn’ …” Louis muttered, staring at the floor. Then, suddenly: “Hello!” – A man’s voice, probably forty-something, the accent refined, educated, the diction strangulated – “I’m sorry but I’m in London right now.” – He is clearly reading a prepared text, his voice is high-pitched and nasal – “Please leave a message after the beep …” – slightly shrill, sophisticated – gay? – “… and I’ll call you as soon as I get back. Speak soon.”

“He’s using a vocoder,” Camille said.

He headed for the bedroom.

*

The far wall was taken up by a huge, mirrored wardrobe. The bed was also covered in blood and faeces. The bloody top sheet had been stripped off and rolled into a ball. An empty Corona bottle lay by the foot of the bed. Next to the head of the bed was a large portable C.D. player and a number of severed fingers laid out like the petals of a flower. Lying beside the player, crushed by the heel of a shoe, was an empty Traveling Wilburys jewel case. Above the bed – one of those low futons with a hard mattress – was a Japanese silk painting whose composition seemed to be enhanced by the arterial blood s. . .

He used her name as a sign of complicity but could not make the slightest dent in her armour. He looked down at the notes scribbled by Armand during the first interview: Alice Vandenbosch, 24. He tried to imagine what 24-year-old Alice Vandenbosch normally looked like. She was probably a young woman with a long, slim face, sandy hair, honest eyes. What he saw when he looked up seemed completely improbable. The girl was nothing like herself: her hair, once blonde, was plastered to her skull and dark at the roots; her face had a sickly pallor, a large purple bruise on her right cheek, thin threads of dried blood at one corner of her mouth … all that was human in her wild, frantic eyes was fear, a fear so terrible she was still shivering as though she had gone out on a winter’s day without a coat. She clutched the plastic coffee cup with both hands, like a lifeline.

Usually, when Camille Verhœven stepped into a room, even the coolest of customers reacted. Not Alice. Alice was shut away inside herself, trembling.

It was 8.30 a.m.

A few minutes earlier, when he had arrived at the brigade criminelle, Camille had felt tired. Dinner the night before had gone on until 1 a.m. People he did not know, friends of Irène. They had talked about television, told stories that Camille might have found quite funny, but for the fact that he was sitting opposite a woman who reminded him of his mother. All through the meal he had tried to dispel the image, but it was uncanny: the same stare, the same mouth, the same cigarettes smoked one after the other. Camille had found himself swept back twenty years to a blessed time when his mother would emerge from her studio wearing a smock smeared with paint, a cigarette dangling from her lips, her hair dishevelled. A time when he would still go to watch her work. She was an Amazon. Solid and focused, with a furious brushstroke. She lived so much inside her head that sometimes she did not seem to notice his presence. Long, silent periods back when he had loved painting, back when he watched her every movement as though it might be the key to some mystery that concerned him personally. That was before. Before the serried ranks of cigarettes declared open war on her, but long after they caused the foetal hypotrophy that marked Camille’s birth. At the time, drawing himself up to his full height – he would never be taller than four foot eleven – Camille did not know which he hated more, the mother whose toxic habit had fashioned him into a kind of pale, slightly less deformed copy of Toulouse-Lautrec, or the meek, powerless father who gazed at his wife with pathetic admiration, as though at his own reflection in a mirror: at sixteen he was already a man, though not in stature. While his mother accumulated canvases in her studio and his laconic father worked at the pharmacy, Camille learned what it meant to be short. As he grew older, he stopped desperately trying to stand on tiptoe, got used to looking at others from below, gave up trying to reach shelves without fetching a stool, laid out his personal space like a doll’s house. And this diminutive man would survey, without really understanding, the vast canvases his mother had to roll up in order to take them to gallery owners. Sometimes his mother would say, “Camille, come here a minute …” Sitting on a stool, she would silently run her fingers through his hair and Camille knew that he loved her; at times he thought he would never love anyone else.

Those were the good times, Camille thought over dinner as he stared at the woman sitting opposite who laughed raucously, drank little and smoked like a chimney. The time before his mother spent her days kneeling next to her bed, resting her cheek on the blankets, the only position in which the cancer gave her a little respite. Illness had brought her to her knees. And though by now each found the other unfathomable, this was the first time that they could look at each other eye to eye. At the time, Camille had sketched a lot, spending long hours in his mother’s now deserted studio. When he decided to go into her room he would find his father, who now also spent half his life on his knees, pressed against his wife, his arm around her shoulders, saying nothing, breathing to the same rhythm as her. Camille was left alone. Camille sketched. Camille killed time and he waited.

By the time he went to law school, his mother weighed as little as one of her paintbrushes. Whenever he came home, his father seemed cloaked in a heavy silence of grief. The whole thing dragged on. And Camille bent his permanently childlike body over his law books and waited for it to end.

It arrived on a May day like any other. The telephone call might almost have been from a stranger. His father said simply, “You should probably come home.” And he knew straight away that from then on he would have to make his own way in the world, that there would never be anyone else.

At forty, this short, bald man with his long, furrowed face knew that this was not true, now that Irène had come into his life. But all these visions from the past had made for an exhausting evening. Besides, game had never really agreed with him.

It was at about the time he was bringing Irène her breakfast on a tray that Alice had been picked up by a squad car on the boulevard Bonne-Nouvelle.

“In ten minutes,” said Camille, “I want you to come and tell me you’ve found Marco. And that he’s in a bad way.”

“Found Marco …?” Armand was puzzled. “Where?”

“What the fuck do I know, just make it happen.”

With short, swift strides, Camille scuttered back to his office.

“So,” he said as he came towards Alice, “Let’s take it again from the beginning.”

He stood facing her, they were almost eye to eye. Alice seemed to wake from her trance. She stared at him as though seeing him for the first time and must have felt more keenly than ever how ridiculous the world was; two hours earlier she had been beaten up, her body was a mass of bruises, now here she sat in the brigade criminelle staring at a man no more than four foot eleven tall who was suggesting they start again from the beginning, as though this nightmare had a beginning.

Camille sat at his desk and automatically picked a pencil from among the dozen or so in the cut-glass desk tidy Irène had given him. He looked at Alice. She was not an ugly girl, rather pretty, in fact. Her delicate, sorrowful features were somewhat gaunt from too many late nights and too little care. A pietà. She looked like a reproduction of a classical statue.

“How long have you been working for Santeny?” he asked, sketching the curve of her face with a single stroke.

“I don’t work for him!”

“O.K., let’s say two years then. So you work for him and he supplies you, is that the deal?”

“No.”

“And you still think he’s in love with you, am I right?”

She glared at him. Camille smiled and looked down at his drawing. There was a long silence. Camille remembered a favourite phrase of his mother’s: “It’s the artist’s heart that beats inside the model’s body.”

On the sketchpad, with a few deft strokes, a different Alice slowly began to appear, younger than the woman sitting opposite, just as sorrowful but not as bruised. Camille looked at her again and seemed to come to a decision. Alice watched as he pulled a chair up next to her and perched on it like a child, his feet dangling.

“Mind if I smoke?” Alice said.

“Santeny’s in deep, deep shit,” Camille said as though he hadn’t heard. “The world and his brother are gunning for him. But you know that better than anyone, don’t you?” he said, gesturing to her bruises. “Not exactly friendly, are they? So it’s probably best that we find him first, don’t you think?”

Alice seemed to be hypnotised by Camille’s shoes, which swung like a two pendulums several inches from the floor.

“He’s got no-one to turn to, no way out of this. I give him a couple of days at most. But then you haven’t got anyone either, have you? They’ll track you down … Now, where’s Santeny?”

A stubborn little pout, like a child who knows she’s doing something wrong but does it anyway.

‘O.K., never mind … you’re free to go,” said Camille, as though talking to himself. “Next time I see you, I hope it’s not at the bottom of a rubbish skip.”

At precisely that moment Armand stepped into the office.

“We’ve just found Marco. You were right, he’s in a terrible way.”

Camille looked at Armand in feigned surprise.

“Where was he?”

“His place.

Camille shot his colleague a pitiful look: even with his imagination Armand was tight-fisted.

“O.K. Anyway, we can let the girl go,” he said, hopping down from the chair.

A little flurry of panic, then:

“He’s in Rambouiller,” muttered Alice under her breath.

“Oh,” said Camille, unimpressed.

“Boulevard Delagrange, number 18.”

“Eighteen,” Camille echoed, as though repeating the number excused him from having to thank the young woman.

Without waiting for permission, Alice took a crumpled cigarette pack from her pocket and lit one.

“Those things will kill you,” Camille said.

Camille was gesturing to Armand to dispatch a squad to the address when the telephone rang. On the other end, Louis sounded out of breath.

“We’ve got a clusterfuck out in Courbevoie,” he panted.

“Do tell …” Camille said laconically, picking up a pen.

“We received an anonymous tip-off this morning. I’m there right now. It’s … I don’t know how to describe it—”

“Why don’t you give it a go,” Camille interrupted fractiously, “see what we come up with.”

“It’s carnage,” Louis said in a strangulated voice, struggling to find the words. “It’s a bloodbath. But not the usual kind, if you see what I mean …”

“I don’t see, Louis, not really.”

“It’s like nothing I’ve ever seen in my life …”

Since his extension was engaged, Camille walked to Commissaire Le Guen’s office. He knocked curtly but did not wait for an answer. He liked to make an entrance.

Le Guen was a big man who had spent more than twenty years following one diet after another without losing a single gram. He had acquired a somewhat weary fatalism which was visible in his face, in his whole body. Camille had noticed that, over the years, he had adopted the air of a deposed king, surveying the world with a sullen, disillusioned expression. Hardly had Camille said a word than Le Guen interrupted him purely on principle, explaining that, whatever it was, “he didn’t have the time”. But when he saw the slim dossier Camille had brought, he decided accompany him to the crime scene nonetheless.

On the telephone Louis had said, “It’s like nothing I’ve ever seen in my life …” This worried Camille; his assistant was not given to doom-mongering. In fact he was exasperatingly optimistic, so Camille expected nothing good of this unexpected call-out. As the Péripherique flashed past, Camille Verhœven could not help but smile thinking about Louis.

Louis was blond, his hair parted to the side, and he had that unruly tuft genetically bestowed upon children of the privileged classes, a wayward curl constantly flicked back with a jerk of the head or a nonchalant yet practised hand. Over time, Camille had learned to distinguish the different messages conveyed by the way he pushed back his hair, a veritable barometer for gauging Louis’ moods. The right-handed variant covered a range of meanings running from “Let’s be reasonable” to “That’s simply not done”. The left-handed variant signalled embarrassment, awkwardness, timidity or confusion. Looking at Louis, it was easy to imagine him as an altar boy. He still had the youthful looks, the grace, the fragility. In short, Louis was elegant, slim, delicate, and a royal pain in the arse.

To crown it all, Louis was loaded. He had all the trappings of the filthy rich: a certain way of deporting himself, a particular way of speaking, of articulating, of choosing his words, everything in fact that comes from the top-shelf mould marked “Rich spoiled brat”. Louis had initially excelled at university (where he had studied a little law, some economics, history of art, aesthetics, psychology), changing courses according to his whims, unfailingly brilliant, treating education as a series of inane achievements. And then something had happened. From what Camille understood, it had to do with Descartes’ dark night of the soul and the demon drink – a combination of philosophical intuition and single malt whisky. Louis had seen his life stretching out before him, in his perfectly appointed six-room apartment lined with bookshelves full of tomes on art and inlaid cabinets filled with designer crockery, the rents from his various properties rolling in like a civil servant’s salary, spending holidays at his mother’s place in Vichy, frequenting the same neighbourhood restaurants, and he found himself confronted by a personal paradox as sudden as it was strange, a genuine existential crisis which anyone other than Louis would have summed up by saying “What the fuck am I doing here?”

Camille was convinced that, had he been born thirty years earlier, Louis would have become a left-wing revolutionary, but these days ideology no longer offered an alternative. Louis despised sanctimoniousness, and by extension voluntary work and charity. He needed to find something to do with his life, his own living hell. And suddenly it became clear to him: he would join the police. Louis never doubted for a moment that he would be accepted into the brigade criminelle – doubt was not a family trait, and Louis’ brilliance meant that he was rarely disillusioned. He passed his police exams and joined the force, motivated partly by a desire to serve (not to Protect and Serve, but simply to serve a purpose), partly by the fear that life would soon become entirely solipsistic and partly, perhaps, out of an imagined debt he felt he owed the working classes for not having been born one of their number. When he passed his detective’s exams, Louis found the world utterly different from how he had imagined it: it had nothing of the quaintness of Agatha Christie or the deductive logic of Conan Doyle; instead Louis found himself faced with filthy hovels and battered wives, drug dealers bleeding to death in rubbish skips in Barbès, knife fights between junkies, putrid toilets where the addicts who survived the fights O.D.’d, rent-boys selling their arses for a line of coke and johns who refused to pay more than €5 for a blowjob after 2 a.m. In the early days, Camille found it entertaining to observe Louis, the blond fringe, the florid vocabulary, his eyes filled with horror but his mind like a steel trap, as he filled out endless reports; Louis imperturbably taking witness statements in echoing, piss-stained stairwells next to the corpse of some thirteen-year-old pimp who had been hacked to death with a machete in front of his mother; Louis heading home at two in the morning to his enormous apartment on the rue Notre-Dame-de-Lorette and collapsing fully dressed on his velvet sofa beneath an engraving by Pavel, between the bookcase of signed first editions and his late father’s collection of amethysts.

When Louis first arrived at the brigade criminelle, the commandant did not immediately take to this smooth, clean-cut young man with the upper-class drawl who seemed unfazed by everything. The other officers on the team, who found it mildly entertaining to spend their days with a golden boy, were ruthless. Within less than two months, Louis had encountered most of the cruel pranks and hazing rituals with which groups humiliate outsiders. Louis accepted his fate without complaint, smiling awkwardly.

Camille noticed earlier than his colleagues that this surprising and intelligent young man had the makings of a good officer but, perhaps trusting to Darwinian selection, he decided not to intervene. Louis, with his rather British stiff upper lip, was grateful to him for that. One evening, as he was leaving the offices, Camille saw Louis dash to the bar across the road and knock back two or three shots. It reminded him of the fight scene in “Cool Hand Luke” where Paul Newman, battered, dazed and unable to land a punch, keeps getting up every time he’s knocked down until the men watching lose heart, even his opponent loses the will to fight. And indeed, faced with Louis’ professional diligence and his surprising ability to appeal to their better nature, the other officers eventually gave up. Over the years, Camille and Louis accepted each other’s differences, and since the commandant enjoyed an undisputed moral authority over the team, no-one was surprised that the rich kid gradually became his closest colleague. Camille always addressed Louis by his first name, as he did everyone on his team. But as time passed and the team changed, he realised that only the longest-serving members called him Camille. These days the team was mostly comprised of rookies, and Camille sometimes felt as though he had usurped a role he had never sought and become patriarch. The rookies addressed him as “commandant”, though he knew this was less to do with hierarchy than an attempt to compensate for the instinctive embarrassment they felt at his diminutive stature. Louis also addressed him by his surname, but Camille knew that his motivation was different: it was a reflex of his class. The two men had never quite become friends, but they respected one another, and both felt that this was a better basis for a good working relationship.

Camille and Armand, with Le Guen trailing behind, arrived at 17, rue Félix-Faure in Courbevoie shortly after 10 a.m. It was an industrial wasteland.

In its centre a small derelict factory lay like a dead insect, surrounded by former workshops that were currently being renovated. The four finished units looked as out of place as Tiki huts in a snowy landscape. All had white rendering, glass roofs, and aluminium windows with sliding panels, offering a glimpse of their vast interiors. The whole place looked deserted. There were no cars save those of the brigade criminelle.

Two steps led up to the warehouse apartment. From behind, Camille saw Louis leaning against a wall, spitting into a plastic bag he kept pressed to his mouth. Camille walked past, followed by Le Guen and two other officers from the team, and stepped into a room lit by the blinding glare of spotlights. When they arrive at a crime scene, rookie officers unconsciously look around for death. Experienced officers look for life. But there was no life here; death had leached into every space, even the bewildered eyes of the living. Camille had no time to worry about the strange atmosphere that pervaded the room as his gaze was immediately arrested by the head of a woman nailed to the wall.

Hardly had he taken three paces into the room than he found himself faced with a scene he could not have imagined even in his worst nightmares: severed fingers, torrents of clotted blood, the stench of excrement and gutted entrails. Instinctively, he was reminded of Goya’s painting, “Saturn Devouring His Son”, and for an instant he could see the terrifying face, the bulging eyes, the crimson mouth, the utter madness. Though he was one of the most experienced officers on the scene, Camille felt the urge to turn back to the doorway where Louis, not meeting anyone’s eye, held his plastic bag at arm’s length, like a beggar declaring his contempt for the world.

“What the fuck is this …?” Commissaire Le Guen muttered to himself, and his words were swallowed by the void. Only Louis heard him and came over, wiping his eyes.

“I don’t know,” he said. “I walked in and had to walk straight back out again … That’s as far as I’ve got.”

Standing in the middle of the room, Armand turned towards the two men, looking dazed. He wiped his clammy hands on his trousers and tried to compose himself.

Bergeret, head of the forensics team from identité judiciaire, went over to Le Guen.

“I’m going to need two teams. This is going to take a while.” Then, with uncharacteristic candour, he added: “It’s not exactly your usual crime scene.”

There was nothing usual about it at all.

“O.K., I’ll leave you to it,” Le Guen said to Maleval, who had just come into the room and was already racing out, both hands clasped over his mouth.

Camille signalled to his team that it was time to man up.

*

It was impossible to imagine what the apartment had looked like before … this. Because “this” had now ravaged the place and they did not know which way to turn. To Camille’s right, sprawled on the ground, were the remains of a disembowelled body, jagged, broken ribs poking through the stomach, and one breast, the other having been hacked off, but it was difficult to say for sure since the body of the woman – that it was a woman was the only thing that seemed certain – was smeared with excrement which only partially covered countless bitemarks. To the left was a head, the eyes burned out. From the gaping mouth snaked pink and white veins. Opposite lay a body from which the skin had been partially peeled away, deep gashes lacerated the flesh and there were yawning wounds, carefully demarcated openings in the belly and vagina, probably made using acid. The head of the second victim had been nailed to the wall through the cheeks. Camille surveyed the scene, and took a notebook from his pocket, only to quickly put it back again as though acknowledging that the task was so monstrous that all his methods were useless, every approach doomed to failure. There is no strategy for dealing with atrocity. And yet this was why he was here, staring at the nameless horror.

Before it had clotted, someone had used the victims’ blood to daub on the wall in huge letters: I AM BACK. It was obvious from the long drips at their base that a lot of blood had been used. The characters had been scrawled using several fingers, sometimes together, sometimes apart, so that the inscription seemed somehow blurred. Camille stepped over the mangled body of a woman and went to the wall. At the end of the sentence, a finger had been pressed against the plaster with great care. Every ridge and whorl was distinct; it looked just like the old-style I.D. cards when a duty officer would press your finger against the yellowing cardboard, rolling it carefully from one side to the other.

Dark sprays of blood spattered the walls all the way to the ceiling.

It took several minutes for Camille to compose himself. It would be impossible for him to think rationally in this setting – everything he could see defied reason.

*

There were about a dozen people now working in the apartment. As in an operating theatre, to outsiders the atmosphere at a crime scene can often seem quite relaxed. People are quick to laugh and joke. It was something Camille loathed. Conversation between S.O.C.O.s was full of crude jokes and sexual innuendo, as though they needed to prove they were blasé. A common attitude in professions that are predominantly male. To a forensics officer accustomed to dissociating horror from reality, the body of a woman – even when dead – is still a woman’s body, a female suicide victim can still be described as “a good-looking woman” even when her face has bloated and turned blue. But the atmosphere in the apartment in Courbevoie was very different. It was neither grieving nor compassionate, but hushed and powerful, as though even the most hard-bitten officers, caught off guard, were wondering how they could possibly make light of a body that had been disembowelled beneath the sightless gaze of a head nailed to the wall. And so, in silence, the forensics team took measurements, collected samples, redirected the spotlights as they snapped photographs, documenting the scene with an almost religious stillness. Though Armand was an experienced officer, his face was deathly pale as he stepped over the crime-scene tape with a ritualised slowness, as though fearing that a sudden movement might rouse the furies that still haunted this place. As for Maleval, he was still puking his guts out into a plastic bag; he had twice tried to join his team only to immediately back away, literally suffocated by the stench of excrement and rotting flesh.

*

The apartment was huge. Despite the mess, it was clear that great care had been taken in decorating it. As in most warehouse apartments of its kind, the front door opened directly onto the living room, a vast space with whitewashed concrete walls. The right-hand wall was filled by an enormous print. You had to step back to get a sense of it. It was an image Camille felt he had seen before. Standing in the doorway, he racked his brains, trying to remember.

“The human genome,” Louis said.

That was what it was: a reproduction of the human genome reworked by an artist in ink and charcoal.

A large picture window looked out onto a development of semi-detached houses in the distance, screened by trees that had not yet had time to grow. A faux cowhide was tacked to one wall, a long rectangular piece of leather daubed with distinctive black and white markings. Beneath it was a black leather sofa of astonishing proportions, probably a bespoke piece of furniture custom-made to the precise dimensions of the wall, but it was impossible to know – this was not a home but a different world, one where people hung giant pictures of the human genome on the wall and hacked young women to pieces after first eviscerating them … Lying on the floor beside the sofa was an issue of GQ magazine. To the right was a well-stocked bar and to the left a coffee table with a cordless phone and an answering machine. Nearby, on a smoked-glass cabinet, was a large flat-screen television.

Armand was kneeling in front of the unit. Camille, who given his height was usually in no position to do so, laid a hand on his shoulder and, gesturing to the V.C.R., said, “Let’s have a look at what’s in there.”

The cassette was rewound. The video showed a dog – a German shepherd wearing a baseball cap – peeling an orange gripped between its front paws and eating the segments. It looked like something from one of those T.V. shows of “hilarious” home videos, the filming amateurish, the framing predictable and crude. In the bottom right-hand corner was a logo for “U.S.-Gag” featuring a smiling cartoon camera.

“Let it run,” Camille said. “You never know.”

He bent over the answering machine. The music on the outgoing message seemed to have been dictated by the zeitgeist. A few years ago, it would have been Pachelbel’s “Canon”. Camille thought he recognised “Spring” from Vivaldi’s “Four Seasons”.

“‘Autumn’ …” Louis muttered, staring at the floor. Then, suddenly: “Hello!” – A man’s voice, probably forty-something, the accent refined, educated, the diction strangulated – “I’m sorry but I’m in London right now.” – He is clearly reading a prepared text, his voice is high-pitched and nasal – “Please leave a message after the beep …” – slightly shrill, sophisticated – gay? – “… and I’ll call you as soon as I get back. Speak soon.”

“He’s using a vocoder,” Camille said.

He headed for the bedroom.

*

The far wall was taken up by a huge, mirrored wardrobe. The bed was also covered in blood and faeces. The bloody top sheet had been stripped off and rolled into a ball. An empty Corona bottle lay by the foot of the bed. Next to the head of the bed was a large portable C.D. player and a number of severed fingers laid out like the petals of a flower. Lying beside the player, crushed by the heel of a shoe, was an empty Traveling Wilburys jewel case. Above the bed – one of those low futons with a hard mattress – was a Japanese silk painting whose composition seemed to be enhanced by the arterial blood s. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved