- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

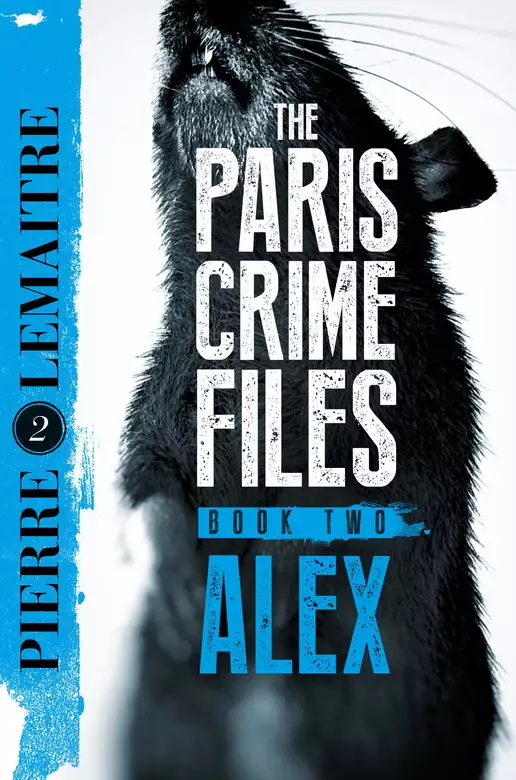

Synopsis

Upon winning the prestigious 2013 Crime Writers Association International Dagger Award, the judges praised Alex by saying, "An original and absorbing ability to leash incredulity in the name of the fictional contract between author and reader... A police procedural, a thriller against time, a race between hunted and hunter, and a whydunnit, written from multiple points of view that explore several apparently parallel stories which finally meet."

Alex Prevost--kidnapped, savagely beaten, suspended from the ceiling of an abandoned warehouse in a tiny wooden cage--is running out of time. Her abductor appears to want only to watch her die. Will hunger, thirst, or the rats get her first?

Apart from a shaky eyewitness report of the abduction, Police Commandant Camille Verhoeven has nothing to go on: no suspect, no leads, and no family or friends anxious to find a missing loved one. The diminutive and brilliant detective knows from bitter experience the urgency of finding the missing woman as quickly as possible--but first he must understand more about her.

As he uncovers the details of the young woman's singular history, Camille is forced to acknowledge that the person he seeks is no ordinary victim. She is beautiful, yes, but also extremely tough and resourceful. Before long, saving Alex's life will be the least of Commandant Verhoeven's considerable challenges.

A 2013 Financial Times Book of the Year

Shortlisted for the 2014 RUSA Reading List Horror Award

(P)2013 Quercus Editions Ltd

Release date: February 14, 2013

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Alex

Pierre Lemaitre

She stumbled on this little shop on the boulevard de Strasbourg by pure chance three or four years ago. She wasn’t really looking, but out of curiosity she went inside and was so astonished seeing herself as a redhead, seeing herself completely transformed, that she bought the wig on the spot.

Alex can wear pretty much anything because she is truly stunning. It wasn’t always that way; it happened in her teens. Before that she had been a scrawny, rather ugly little girl. But when she finally blossomed it was like a tidal wave, like a computer morphing programme on fast forward; in a few short months Alex became a devastating young woman. Perhaps because by then everyone – particularly Alex – had given up hope that she would ever be beautiful, she has never really thought of herself as beautiful. Even now.

For example, it had never occurred to her that she could wear a red wig. It had been a revelation. She couldn’t believe how different she looked. Wigs seemed so superficial and yet the moment she first put one on, she felt her whole life had changed.

In the end she hardly ever wore it, that first wig. As soon as she got it home she realised that it looked tawdry, cheap. She tossed it. Not into the bin, but into the bottom drawer of her dresser. Every now and again she would take it out, try it on, gaze at herself in the mirror. Though it was indeed hideous, the sort of thing that screamed “tacky nylon fright-wig”, what Alex saw when she looked in the mirror kindled a hope in which she wanted to believe. And so she went back to the shop on the boulevard de Strasbourg and lingered over elegant, high-quality wigs that were a little beyond the means of an agency nurse. But they looked astonishingly real. And she took the plunge.

At first it wasn’t easy; it still isn’t, it takes nerve. For a shy, insecure girl like Alex, just getting up the nerve could take half a day. Putting on the right make-up, finding the perfect outfit, the matching shoes and handbag (well, rummaging through the wardrobe to find something that might match, since she can’t afford to buy a new outfit every time …) But then comes the moment when you step out into the street and you’re someone else. Not entirely, but almost. And though it’s hardly earth-shattering, it passes the time, especially when you’re not expecting much from life.

Alex prefers wigs that make a statement, wigs that say, I know what you’re thinking, or I’m not just a pretty face, I’m a maths genius too. The wig she’s wearing today says, You won’t find me on Facebook.

As she picks up a wig called “Urban Shock” she glances out through the shop window and she sees the man. He is standing on the far side of the street pretending to be waiting for someone or something. This is the third time in two hours she has seen him. He is following her. She now realises that he must be. Her first thought is “Why me?”, as though she could understand why a man might follow any other girl, but not her. As though she didn’t forever have men looking at her, on the bus, in the street. In shops. Alex attracts attention from men of all ages. It’s one of the benefits of being thirty. And yet every time it happens, she feels surprised. “There are much prettier girls out there than me.” Alex is chronically insecure, crippled by self-doubt. She has been since she was a child. Until her teens she had a terrible stammer. Even now she stammers when she’s nervous.

She doesn’t recognise the man; she has never seen him before – with a body like that, she would remember. What’s more, it seems strange, a guy of fifty following a girl of thirty … It’s not that she’s ageist – far from it – she’s just surprised.

Alex looks down at the wigs, pretends to hesitate, then wanders over to the other side of the shop from where she has a good view of the street. From the cut of his clothes you can tell he was once an athlete of some sort, a heavyweight. Stroking a platinum blonde wig, she tries to work out when she first noticed him. She remembers seeing him in the métro; their eyes met for a moment – though long enough for her to notice the smile intended for her, a smile clearly meant to be warm and winning. What troubles her about him is the obsessiveness in his eyes. And his lips, so thin as to be almost non-existent. She felt instinctively suspicious, as though somehow all thin-lipped people are hiding something, some unspeakable secret, some terrible vice. And his high, domed forehead. Unfortunately, she didn’t really have time to study his eyes. The eyes never lie, Alex believes, and it is by their eyes that she judges people. Obviously, in the métro, with a guy like that, she hadn’t wanted to linger.

Discreetly, almost imperceptibly, she turned so that her back was to him, rummaging in her bag for her iPod. She put on “Nobody’s Child”, and as she did she wondered if she hadn’t seen him hanging around outside her building the day before, maybe two days ago. It’s vague, she can’t be sure; the memory might be clearer if she turned to look again, but she doesn’t want to lead him on. What she does know is that two hours after seeing him in the métro, she spotted him as she turned again onto the boulevard de Strasbourg. On a whim she had decided to go back to the shop and try on the mid-length auburn wig with the fringe and as she turned round, she spotted him a little way away, saw him stop dead and pretend to look at something in the window … of a women’s dress shop. It was pointless for him to pretend …

Alex sets down the wig. For no reason her hands are trembling. She’s being ridiculous. The guy fancies her; he’s following her, thinks he’s in with a chance – he’s hardly going to attack her in the street. Alex shakes her head as though trying to make up her mind and when she looks out at the street again, the man has disappeared. She leans first one way then the other, but there’s no-one; he has gone. The relief she feels seems somehow disproportionate. “I’m just being silly,” she thinks again, as her breathing begins to return to normal. In the doorway of the shop, she can’t help but stop and check the street again. It almost feels as though it’s his absence now that worries her.

Alex checks her watch, looks up at the sky. The weather is mild and there’s at least an hour of daylight still. She doesn’t feel like heading home. She needs to stop off and buy food. She tries to remember what she’s got in the fridge. She’s always been a bit lax about grocery shopping. She tends to focus all her energy on her work, her comfort (Alex is a little obsessive-compulsive), and – though she’s reluctant to admit it – on clothes and shoes. Plus handbags. And wigs. She wishes her love life had worked out differently; it’s something of a touchy subject. Her love life is a disaster area. She hoped, she waited, and eventually she gave up. These days, she thinks about it as little as possible. But she is careful not to allow regret to turn into ready-meals and nights in front of the television, careful not to put on weight, not to let herself go. Though she’s single, she rarely feels alone. She has lots of projects that are important to her and they keep her busy. Her love life might be a train wreck, but that’s life. And it’s easier now that she’s resigned herself to being alone. In spite of her loneliness, Alex tries to live a normal life, to enjoy her little pleasures. It consoles her to think that she can indulge herself, that like everyone else she has the right to indulge herself. Tonight, for example, she’s decided to treat herself to dinner at Mont-Tonnerre on the rue de Vaugirard.

*

She arrives a little early. It’s her second time. The first was a week ago and the staff obviously remember the attractive redhead who was dining alone. Tonight they greet her like a regular, the waiters jostling to serve her, flirting awkwardly with the pretty customer. She smiles at them, effortlessly charms them. She asks for the same table, her back to the terrace, facing into the room; she orders the same half-bottle of Alsatian ice wine. She sighs. Alex loves food, so much so that she has to be careful. Her weight keeps fluctuating, but she has learned to control it. Sometimes she will put on ten or fifteen kilos, become virtually unrecognisable, but two months later she’s back to her original weight. It’s something she won’t be able to get away with a few years from now.

She takes out her book and asks for an extra fork to prop it open with while she’s eating. Sitting facing her is the guy with light brown hair she saw here last week. He’s having dinner with friends. For the moment there are only two of them, but it’s clear from their talk that they are expecting others to turn up soon. He spotted her the moment she stepped into the restaurant. She pretends not to notice him staring at her intently. He will stare at her all night, even when the rest of his friends show up and they launch into their endless banter about work, about girls, about women, taking turns telling stories that make them sound good. All the while, he will be glancing at her. He’s not bad looking – forty, forty-five maybe – and he was clearly handsome as a young man; he drinks a little too much, which explains his tragic face. A face that stirs something in Alex.

She drinks her coffee and – her one concession – as she leaves, she gives him a look; she does it expertly. A fleeting glance, the sort of look Alex does perfectly. Seeing the longing in his eyes, for a split-second she feels a twinge of pain in the pit of her stomach, an intimation of sadness. At moments like this Alex never articulates what she is feeling, certainly not to herself. Her life is a series of frozen images, a spool of film that has snapped in the projector – it is impossible for her to rewind, to refashion her story, to find new words. The next time she has dinner here, she might stay a little later, and he might be waiting for her outside when she leaves – who knows? Alex knows. Alex knows all too well how these things go. It’s always the same story. Her fleeting encounters with men never become love stories; this is a part of the film she’s seen many times, a part she remembers. That’s just the way it is.

It is completely dark now and the night is warm. A bus has just pulled up. She quickens her step, the driver sees her in the rear-view mirror and waits, she runs for the bus but just as she’s about to get on, changes her mind, decides to walk a little way. She signals to the driver who gives a regretful shrug, as if to say Oh well, such is life. He opens the bus door anyway.

“There won’t be another bus after me. I’m the last one tonight …”

Alex smiles, thanks him with a wave. It doesn’t matter. She’ll walk the rest of the way. She’ll take the rue Falguière and then the rue Labrouste.

She’s been living near the Porte de Vanves for three months now. She moves around a lot. Before this, she lived near Porte de Clignancourt and before that on the rue du Commerce. Most people hate moving, but for Alex it’s a need. She positively enjoys it. Maybe because, as with the wigs, it feels like she’s changing her life. It’s a recurring theme. One day she’ll change her life.

A little way in front of her, a white van pulls onto the pavement to park. To get past, Alex has to squeeze between the van and the building. She senses a presence, a man; she has no time to turn. A fist slams between her shoulder blades, leaving her breathless. She loses her balance, topples forward, her forehead banging violently against the van with a dull clang; she drops everything she’s carrying, her hands flailing desperately to find something to catch hold of – they find nothing. The man grabs her hair, but the wig comes off in his hand. He curses, a word she can’t quite make out, then viciously yanks her real hair with one hand, and with the other punches her in the stomach hard enough to stun a bull. Alex doesn’t have time to scream; she doubles over and vomits. The man has to be very powerful because he manages to flip her like a piece of paper so that she is facing him. His arm slides round her waist, pulling her against him while he stuffs a wad of tissue paper into her mouth and down her throat. It’s him: the man she saw in the métro, in the street, outside the shop. It’s him. For a fraction of a second they look each other in the eye. She tries to struggle, but he’s got her arms in a tight grip, there’s nothing she can do, he’s too strong, he pushes her down, her knees give way, she falls onto the floor of the van. He lashes out, a vicious kick to the small of the back, sending Alex sprawling into the van, the floor grazing her cheek. He climbs in behind her, forcibly turns her over and punches her in the face. He hits her so hard … This guy really wants to hurt her, he wants to kill her – this is what’s going through Alex’s mind as she feels the punch. Her skull slams against the floor of the van and bounces and she feels a shooting pain in the back of her head – the occiput, that’s what it’s called, Alex thinks, the occiput. But apart from this word, the only thing she can think is, I don’t want to die, not like this, not now. Huddled in a foetal position, mouth full of vomit, she feels her arms wrenched hard behind her back and tightly bound, then her ankles. “I don’t want to die now,” Alex thinks. The door of the van slams shut, the engine roars into life, the van pulls away from the pavement with a screech. “I don’t want to die now.”

Alex is dazed but aware of what is happening to her. She is crying, choking on her tears. Why me? Why me?

I don’t want to die. Not now.

When he called, Divisionnaire Le Guen gave him no choice.

“I don’t give a shit about your scruples, Camille, you’re seriously busting my balls here. I haven’t got anyone else, and I mean anyone, so I’m sending a car for you and you’re fucking going!”

He paused a beat, then, for good measure, he added: “And stop being such a pain in the arse.”

Then he hung up. This is Le Guen’s style. Impulsive. Usually Camille takes no notice of him. Usually he knows how to handle the divisionnaire.

The difference this time is that it’s a kidnapping.

And Camille wants nothing to do with it. He’s made his position clear: there aren’t many cases he won’t handle, but kidnapping is top of the list. Not since Irène died. His wife had collapsed in the street, eight months pregnant, and been rushed to hospital; then she’d been kidnapped. She was never seen alive again. It destroyed Camille. Distraught doesn’t begin to describe it; he was traumatised. He had spent whole days paralysed, hallucinating. When he became delusional, he had had to be sectioned. He was shunted from psychiatric clinics to convalescent homes. It was a miracle he was alive. No-one expected it. In the months on sick leave from the brigade criminelle – the murder squad – everyone had wondered whether he would ever show his face again. And when finally he came back, the strange thing was that he was exactly the same as before Irène’s death, just a little older. Since then, he’s only taken on minor cases: crimes of passion, brawls between colleagues, murder between neighbours. Cases where the deaths are behind you, not in front. No kidnappings. Camille wants his dead well and truly dead, corpses with no comeback.

“Give me a break,” Le Guen has told him more than once – he’s doing the best he can for Camille – “you can’t exactly avoid the living; there’s no future in it. Might as well be an undertaker.”

“But …” Camille said, “that’s exactly what we are!”

They have known each other for twenty years and they like each other. Le Guen is a Camille who gave up on the streets. Camille is a Le Guen who gave up on power. The obvious differences between them are two pay grades and fifty-two pounds. That, and about eleven inches. Put like that it sounds preposterous, and it’s true that when they’re together they look like cartoon characters. Le Guen is not very tall, but Camille is positively stunted. He sees the world from the viewpoint of a thirteen-year-old. This is something he gets from his mother, the artist Maud Verhœven. Her paintings are in the collections of a dozen museums abroad. She was an inspired artist and an incorrigible smoker who lived in a cloud of cigarette smoke, a permanent halo; it is impossible to imagine her without that blue haze. It is to her that Camille owes his two distinguishing traits. The artist left him with an exceptional talent for drawing; the inveterate smoker left him with foetal hypotrophy, which meant he never grew taller than four foot eleven.

He has rarely met anyone he could look down on; he has spent his life looking up at people. His height goes beyond a mere handicap. At the age of twenty it’s an appalling humiliation, at thirty it’s a curse, but from the outset it’s clearly a destiny. The sort of handicap that makes a person resort to using long words.

With Irène, Camille’s height became a strength. Irène had made him taller on the inside. Camille had never felt so … he gropes for a word. Without Irène, he’s lost for words.

Le Guen on the other hand qualifies as colossal. No-one knows how much he weighs; he refuses to discuss it. Some people claim he’s at least 120 kilos, others say 130 kilos, and there are some people who think it’s more. It doesn’t matter: Le Guen is gargantuan, an elephantine man with hamster cheeks, but because he has bright eyes brimming with intelligence – no-one can explain this, men are reluctant to admit it, but most women are agreed – the divisionnaire is a very attractive man. Go figure.

Camille is accustomed to Le Guen’s tantrums; he’s not impressed by histrionics. They’ve known each other too long. Calmly he picks up the telephone and calls the divisionnaire back.

“Listen up, Jean: I’ll go, I’ll take on this kidnapping of yours. But the fucking second Morel gets back you’re putting him on it, because …” he takes a breath, then hammers home every syllable with a calmness that is filled with menace, “I’m not taking the case!”

Camille Verhœven never shouts. Or very rarely. He is a man of authority. He may be short, bald and scrawny, but this is something that everyone knows. Camille is a razor blade. And Le Guen is careful not to say anything. Malicious gossip has it that Camille wears the trousers in their relationship. It’s not something they joke about. Camille hangs up.

“Fuck!”

This is all he needs. It’s not as if they get kidnapping cases every day; this isn’t Mexico City. Why couldn’t it have happened some other day, when he was on another case, on leave, somewhere, anywhere! Camille slams his fist on the table. But he does so slowly, because he’s a reasonable man. He doesn’t like outbursts, even in other people.

Time is short. He gets to his feet, grabs his coat and hat and takes the stairs two at a time. Camille walks with a heavy tread. Before Irène died, he walked with a spring in his step. His wife used to say, “You hop like a bird. I always think you’re about to take off.” It has been four years since Irène died.

The car pulls up in front of him. Camille clambers inside.

“What’s your name again?”

“Alexandre, bos—”

The driver bites his tongue. Everyone knows Camille hates to be called “boss”. Says it sounds like a T.V. police show. This is Camille’s style: he is very cut-and-dried, a pacifist with a brutal streak. Sometimes he gets carried away. He was always a bit of an oddball, but age and widowhood have made him touchy and irritable. Deep down, he’s angry. Irène used to say, “Darling, why are you always so angry?” Drawing himself up to his four feet eleven inches, and laying the irony on thick, Camille would say, “You’re right. I mean … what have I got to be angry about?” Hot-head and stoic, thug and tactician, people rarely get the measure of Camille on first meeting. Rarely appreciate him. This might also be because he’s not exactly cheerful. Camille doesn’t like himself very much.

Since going back to work three years ago, Camille has taken responsibility for all interns, a blessing for the duty sergeants who can’t be arsed babysitting them. What Camille wants, since his own imploded, is to rebuild a loyal team.

He glances at Alexandre. Whatever he looks like it’s not an Alexandre, but he’s alexandrine enough to be four heads taller than Camille, which isn’t much of a feat, and he set off without waiting for Camille to give the order, which at least shows he’s got some bottle.

Alexandre drives like a maniac; he loves driving, and it shows. The G.P.S. system seems to be having trouble catching up with him. Alexandre wants to show the commandant he’s a good driver – the siren wails, the car speeds assertively through streets, junctions, boulevards; Camille’s feet dangle twenty centimetres off the floor, his right hand gripping his seat belt. In less than fifteen minutes they’re at the crime scene. It is 9.50 p.m. Though it’s not particularly late, Paris already seems peaceful, half asleep, not the sort of city where people are kidnapped. “A woman,” according to the witness who called the police, clearly in a state of shock, “kidnapped, before my very eyes.” The man couldn’t believe it. Then again, it’s not exactly a common occurrence.

“You can drop me here,” Camille says.

Camille gets out of the car, straightens his cap; the driver leaves. They’re at the end of the street, about fifty metres from the cordon. Camille walks the rest of the way. When there’s time, he always likes to view the problem from a distance – that’s how he likes to work. The first view is crucial, so it’s best to take in the whole crime scene; before you know it you’re caught up in countless facts, in details, and there’s no way back. This is the official reason he gives for getting out a hundred metres from where a crowd is standing waiting for him. The other reason, the real reason, is that he doesn’t want to be here.

As he walks towards the police cars, their lights strobing the buildings, he tries to work out exactly what he is feeling.

His heart is hammering.

He feels like shit. He’d give ten years of his life to be somewhere else.

But however slowly and reluctantly he walks, he’s here now.

This is more or less how it happened four years ago. On the street where he lived, which looks a little like this one. Irène wasn’t there. She was due to give birth to a little boy in a few days. She should have been at the maternity unit. Camille raced around, ran everywhere searching for her, did everything he could that night to find her … He was like a madman, but there was nothing he could do. When they found her, she was dead.

Camille’s nightmare had begun in a moment just like this one. This is why his heart is pounding fit to burst, why his ears are ringing. His guilt, the guilt he thought was dormant, has woken. He feels physically sick. A voice inside him screams, Get away; another voice says, Stay and face it; his chest feels tight. Camille is afraid he might pass out. Instead, he moves one of the barriers and steps into the cordoned area. From a distance, the duty officer acknowledges him with a wave. Even those who don’t know Commandant Verhœven personally know him by sight. It’s hardly surprising. Even if he wasn’t some sort of living legend, they know about his height. And his past …

*

“Oh, it’s you.”

“You sound disappointed.”

Flustered, Louis starts to panic.

“No, no, not at all.”

Camille smiles. He’s always had a knack for winding Louis up. Louis Mariani has been his assistant for a very long time and he knows him as well as if he’d knitted the man himself.

At first, after Irène was murdered, after Camille’s breakdown, Louis used to visit him at the clinic. Camille hadn’t talked much. Sketching, which until then had been a hobby, suddenly became his chief, in fact his only activity. Pictures, drawings and sketches lay in heaps around a room that Camille had otherwise left institutionally spartan. Louis would make a place for himself and they would sit, one staring out at the trees, the other down at his feet. They said many things in that silence, but it was no match for conversation. They simply couldn’t find the words. Then one day, without warning, Camille said he would rather be left alone, that he didn’t want to drag Louis into his grief. “A miserable policeman isn’t exactly riveting company,” he said. It was tough on both of them, being separated. But time passed. By the time things had improved, it was too late. After grief, all that remains is barren.

They haven’t seen a lot of each other for a long time now; they run into each other at meetings, briefings, that kind of thing. Louis hasn’t changed much. If he lives to be a hundred, he’ll die young – some people are like that. And he’s as dapper as ever. Camille once said to him, “If I was dressed for a wedding, I’d still look like a tramp next to you.” Louis, it has to be said, is rich: filthy rich. His personal fortune is like Le Guen’s weight: nobody knows what it amounts to, but everyone knows it’s fat and getting fatter. Louis could live off his private income for four or five generations. Instead, he works as a policeman for the murder squad. He did a bunch of degrees he didn’t need, and has such a breadth of knowledge Camille has never caught him out. There’s no denying Louis is a queer fish.

He smiles. It’s weird Camille just showing up like this without warning.

“It’s over there,” he says, nodding towards the police tape.

Camille hurries after the younger man. Though he’s not so young anymore.

“How old are you, Louis?”

Louis turns.

“Thirty-four. Why?”

“Nothing. Just curious.”

Camille realises they’re a stone’s throw from the Bourdelle Museum. He can clearly remember the face of “Hercules the Archer”, the hero triumphing over monsters. Camille has never sculpted – he never had the physique for it – and he hasn’t painted for a long time now, but he still sketches. Even after his long bout of depression, he can’t stop. It’s part of who he is; he has always got a pencil in his hand – it’s his way of looking at the world.

“You ever seen ‘Hercules the Archer’ at the Bourdelle Museum?”

“Yeah,” Louis says and looks confused. “You sure it’s not in the Musée d’Orsay?”

“Still an irritating smart-arse, then.”

Louis smiles. Coming from Camille, this kind of quip means “You know I care about you”. It means, “Jesus, time flies, how long have we known each other?” Mostly, it means, “We haven’t seen a lot of each other since I killed Irène, have we?” So it’s weird the two of them being at the same crime scene. Camille suddenly feels the n. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...