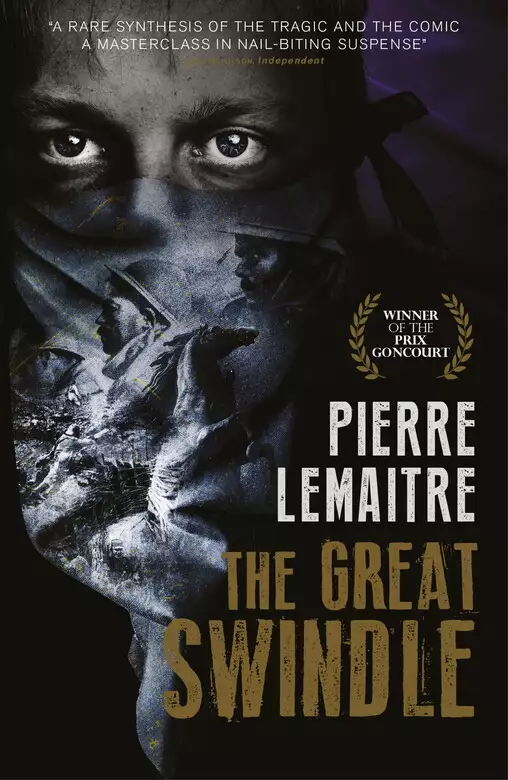

The Great Swindle

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

1918. Wanting to impress his superiors, an ambitious officer, Lieutenant Pradelle, sends two soldiers over the top and shoots them to incite their comrades to attack the German lines. When Albert Maillard realises how they must have died, the Lieutenant hopes to silence him, but Albert is rescued by fellow soldier, Edouard Péricourt. Back in civilian life, Edouard's sense of mischief is rekindled and he devises a confidence trick that could make them a fortune…

Release date: November 5, 2015

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Great Swindle

Pierre Lemaitre

He knew all too well that his refusal to believe in this armistice was a sort of conjuration: in order to ward off ill fortune, the more a man hopes for peace, the less inclined he is to believe the news that it is imminent. Yet day after day, the news came in ever-increasing waves and everywhere people were beginning to say that the war truly was coming to an end. He even read speeches he could scarcely believe about the need to demobilise the older soldiers who had been on the front lines for years. When, finally, the armistice seemed a credible prospect, even the most pessimistic souls began to nurture the hope they might get out alive. Consequently, no-one was particularly keen to mount an offensive. There was talk of the 163rd Infantry Division attempting to mount an attack and cross the Meuse. A few officers still talked about fighting to the death but, seen from the ranks, from the position of Albert and his comrades, since the Allied victory in Flanders, the liberation of Lille, the rout of the Austrian army and the capitulation of the Turks, the ordinary soldiers felt rather less frenzied than the officers. The successes of the Italian offensive, the British at Tournai, the Americans at Châtillon . . . it seemed clear the worst was behind them. Most men in the unit began to play for time and there was a clear distinction between those, like Albert, who were prepared cheerfully to wait out the war holed up in their trenches, smoking cigarettes and writing letters home, and those eager to make the most of the last few days to gut a few more Krauts.

This demarcation line exactly corresponded to the one separating officers from ordinary soldiers. Nothing new there, thought Albert. The commanders want to take control of as much terrain as they can to be in a stronger position at the negotiating table. They will insist that gaining another thirty metres could decide the outcome of the war, that it would be even more worthwhile to die today than yesterday.

This latter position was the one espoused by Lieutenant d’Aulnay-Pradelle. When talking of him, everyone dropped the first name, the nobiliary particle, the “Aulnay” and the hyphen, referring to him simply as “Pradelle” since they knew very well how much this riled him. They could afford to do so, since Pradelle made it a point of honour never to express personal animus. An aristocratic reflex. Albert did not like the man. Perhaps because he was handsome. Tall, thin, elegant, with a cascade of dark brown curls, a straight nose, thin, perfectly shaped lips. And eyes of deepest blue. A face that Albert considered typical of an upper-class twat. Moreover, he seemed to be permanently angry. He was impetuous, he had no cruising speed: he was either accelerating or braking; there was no middle ground. He walked quickly, one shoulder forward as though to push obstacles aside, he bore down on you at speed and even sat down briskly, this was his normal rhythm. It made for a curious combination: with his aristocratic bearing, he seemed at once terribly civilised and utterly brutish. A little like this war. Which was perhaps why he felt so at ease here. To top it all, he had an athlete’s build – rowing, probably, or tennis.

The other thing Albert did not like was the hair. Pradelle had thick dark hair all over, even on his fingers, great tufts sprouted from his shirt collar just below his Adam’s apple. In peacetime, he probably had to shave several times a day so as not to look louche. There were certainly some women who were attracted by that wild, hirsute, faintly Spanish look. Even Cécile . . . But even without thinking of Cécile, Albert could not abide Lieutenant Pradelle. And most of all he feared the man. Because Pradelle liked to charge. He genuinely enjoyed going over the top, storming, attacking.

In fact, recently he had been less high-spirited than usual. The prospect of an armistice depressed him, it undermined his patriotic zeal. The idea that the war might be over was killing Lieutenant Pradelle. He was showing disturbing signs of impatience. He found the lack of team spirit deeply worrisome. As he strode through the trenches and spoke to the men, his passionate zeal and his talk of crushing the enemy, of a final surge that would be the coup de grâce, was met with vague mutterings, the soldiers would nod, staring down at their boots. It was not just the fear of dying, but the fear of dying now. Dying last was like dying first, Albert thought to himself, it was rank stupidity.

But this was exactly what was about to happen.

Whereas until now they had been able to while away the uneventful days waiting for the armistice, now, suddenly, things were gearing up again. Orders had been received from on high, demanding that they approach enemy lines to find out what the Germans were up to. Despite the fact that it did not take a général to know that they, like the French, were waiting for the end. Even so, they had to go and see. From this point, no-one was able to piece together the sequence of events.

It was difficult to know why Lieutenant Pradelle assigned the reconnaissance mission to Gaston Grisonnier and Louis Thérieux, an old man and a kid. Perhaps he hoped to combine youthful vigour with mature experience. Neither quality proved useful, since the two men were dead within half an hour of being allocated the task. In theory, they did not have to advance very far. They only needed to follow a line about two hundred metres to the northeast, cut through the wires, crawl to the second line of barbed wire, have a quick look and then hightail it back to say everything was fine, because everyone knew there was nothing to see. And in fact the two soldiers were not worried about approaching the enemy lines. Given the state of affairs in recent days, even if they were spotted, the Huns would let them reconnoitre and go back, it was little more than a distraction. But the moment they started to advance, crouching as low as they could, the two scouts were shot like rabbits. There was the sound of gunshots, three of them, and then silence; as far as the enemy was concerned, the matter was settled. There was a frantic attempt to see where they were, but since they had left from the north side, it was impossible to tell where they had fallen.

All around Albert everyone stood in stunned silence. Then suddenly there were shouts. Bastards! They’re all the same, the fucking Boche! Savages! To gun down an old man and a kid! Not that this made any difference, but to the men in the trenches the Boche had not simply killed a couple of French soldiers, they had slaughtered two symbols. There was pandemonium.

In the minutes that followed, with a promptness no-one thought them capable of, the rear gunners began pounding the German lines with 75mm shells, leaving the men in the front line wondering how they knew what had happened.

So began the escalating spiral of violence.

The Germans returned fire. It did not take long to mobilise everyone in the French trenches. They would show the fucking Boche a thing or two. It was November 2, 1918. Though no-one knew it, this was scarcely ten days from the end of the war.

And to launch an attack on All Souls’ Day, the Day of the Dead . . . Try as one might to ignore the omens . . .

Here we go again, thought Albert, getting ready to climb the scaffold (this was what they called the stepladders used to scrabble out of the trenches – a cheering thought) and charge, head down, towards the enemy. Lined up in Indian file, the men were swallowing hard. Albert was third in line behind Berry and young Péricourt who turned round as though to check that the men were all present and correct. Their eyes met, Péricourt gave him a smile like a little boy about to play a prank. Albert tried to return the smile but failed. Péricourt turned away again. The feverishness was almost palpable as they waited for the order to attack. Shocked by the outrageous behaviour of the Boche, the French soldiers were now seething. Above them, shells streaked the sky in both directions, causing the very bowels of the earth to shake.

Albert looked over Berry’s shoulder. Perched on his little outpost, Lieutenant Pradelle was peering through binoculars, surveying the enemy lines. Albert returned to his position in the line. Had it not been for the deafening racket, he would have been able to think about what was worrying him. The shrill whistle of the shells increased, punctuated by booming explosions that shook the men from head to foot. Try concentrating in such conditions.

Just now, the lads are standing, waiting for the signal to advance. It seems an apt moment to study Albert.

Albert Maillard was a scrawny boy of a somewhat lethargic disposition, reserved. He spoke little, was good with figures. Before the war, he was a teller in a regional branch of the Parisian Banque de l’Union. He did not much enjoy the work but stuck it out because of his mother. Mme Maillard had only one son and she loved managers. She was ecstatic at the prospect of Albert as a bank manager and convinced that “with his intelligence” he would soon rise to the top. This inflated taste for authority she had inherited from her father, an assistant deputy chief clerk at the Ministère des Postes who considered the ministerial hierarchy a metaphor for the universe. Mme Maillard loved all leaders without exception. She was not particular about their virtues or their provenance. She had photographs of Clemenceau, of Maurras, of Jaurès, Joffre, Briand . . .1

Since the death of her husband, who had commanded a squadron of uniformed guards at the Louvre, exceptional men had inspired extraordinary sensations in her. Albert was not keen on the bank, but allowed himself to be persuaded, with his mother this was always the best policy. But he had begun to make plans. He had longed to escape, he dreamed of running away to Tonkin, though his plans were rather vague. At the very least he would quit his job as a bank teller and do something else. But Albert was not a man in a hurry; everything took time. Then, shortly afterwards, he had met Cécile, had fallen passionately in love with Cécile’s eyes, Cécile’s mouth, Cécile’s smile and, before long, Cécile’s breasts, Cécile’s arse, how could he be expected to think about anything else?

Nowadays, at 1.73m, Albert Maillard would not seem especially tall, but in those days it was tall enough. There was a time when he had turned girls’ heads. Cécile’s in particular. Well . . . it would be more accurate to say that she turned Albert’s head and, after a while, the fact that he stared at her all the time meant that she noticed his existence and she in turn began to stare at him. He had a face that could melt your heart. A bullet had grazed his temple during the Battle of the Somme. He had been terrified, but he came through with nothing more than a scar shaped like a parenthesis, which tugged his eye slightly to one side and gave him a dashing air. When he was next home on leave, Cécile dreamily, curiously, caressed the scar with her forefinger, which did little for his morale. As a child, Albert had had a pale, round face with drooping eyelids that made him look like a mournful Pierrot. Mme Maillard would go without food so that she could feed him red meat, convinced that his pallor was caused by lack of blood. Though Albert told her a thousand times that there was no connection, his mother rarely changed her mind, she would find examples, new reasons, she could not bear to be in the wrong; even in her letters she would dredge up events from years gone by, it was exhausting. One might wonder whether this was why Albert enlisted as soon as war was declared. When she found out, Mme Maillard let out a loud wail, but as she was a demonstrative woman it was difficult to distinguish genuine fear from sheer theatrics. She had screamed and torn her hair, but she quickly pulled herself together. Since she had a conventional view of war, she persuaded herself that Albert – “with his intelligence” – would stand out from the crowd and soon be promoted, she could picture him on the front lines leading an assault. In her imagination, he would perform some heroic feat and immediately ascend to the officer class to become capitaine, commandant or even général – such things happened in war.

With Cécile, things were very different. War did not frighten her. Firstly because it was a “patriotic duty” (Albert was surprised, he had never heard her utter the words before); secondly, there was no real reason to be frightened, the outcome was a formality. Everyone said as much.

Albert, for his part, had his doubts, but Cécile was rather like Mme Maillard, she had fixed ideas. To hear her talk, the war would not last long. Albert almost believed her; no matter what she said, Cécile, with those hands, those lips, could convince Albert of anything. It’s impossible to understand if you don’t know her, thought Albert. To us, Cécile would seem like a pretty girl, nothing more. To him, she was different. Every pore in Cécile’s skin was a molecular miracle, her breath had a rare perfume. She had blue eyes and that might not seem much to you, but to Albert those eyes were a precipice, a yawning chasm. Take her lips, for example, and try to put yourself in Albert’s shoes. From these lips he had known kisses of exquisite warmth and tenderness, kisses that caused his stomach to lurch, his whole being to explode, he had felt Cécile’s saliva flow into him and had drunk it passionately; Cécile was capable of such wondrous feats that she was not merely Cécile. She was . . . she was . . .

And so, when she insisted the war would be a piece of cake, Albert could only think of those lips and imagine he was that piece of cake . . .

Now he saw things rather differently. He knew that war was nothing more than a gigantic game of Russian roulette, and that to survive for four years was little short of a miracle.

To be buried alive when the end of the war was finally in sight would truly be the icing on the cake.

And yet, that is exactly what is about to happen.

Little Albert, buried alive.

“Hap and mishap govern the world,” as his mother would say.

Lieutenant Pradelle turned back to his troops, his eyes boring into the men to left and right who gazed back as though he were the Messiah. He nodded slowly and took a deep breath.

A few minutes later, half crouching, Albert is running through an apocalyptic landscape as shells rain down and bullets whistle through the air, pressing onward, his head drawn in, clutching his rifle as hard as he can. The ground beneath his heavy boots is claggy because it has been raining now for several days. All around him there are men howling like lunatics, drunk on their own bravado, steeling themselves for battle. Others, like him, are concentrating hard, their stomachs in knots, their throats dry. All of them are converging on the enemy, armed with righteous rage and the thirst for vengeance. In fact, this may be a perverse result of the rumoured armistice. They have suffered for so long that to see the war end like this, with so many of their friends dead and so many enemies still alive, they have half a mind to massacre the enemy, to put an end to this war once and for all. They are prepared to slaughter anyone.

Even Albert, terrified at the thought of dying, is ready to gut the first man he encounters. But there are many obstacles along the way; as he runs, he veers towards the right. At first, he advanced along the line indicated by the lieutenant, but as the bullets whined and the shells droned, he had no choice but to zigzag. Especially since Péricourt, directly ahead of him, has just been hit by a bullet and crumpled at his feet so suddenly that Albert scarcely had time to step over him. He loses his balance, staggers a few metres more, carried forward by momentum, only to stumble upon the body of old Grisonnier whose unexpected death triggered this final, bloody slaughter.

Despite the bullets whistling all around, when Albert sees him sprawled there, he stops in his tracks.

He recognises Grisonnier by his greatcoat, because the old man always wore something red in his buttonhole, “my Légion d’horreur”, he called it. Grisonnier was not a great wit. He was not exactly subtle, but he was a brave man and everyone loved him. There could be no doubt that it was him. His huge head was buried in the mud and the rest of his body looked as though he had fallen headlong. Next to him, Albert recognised the kid, Louis Thérieux. He, too, is partly covered by mud, huddled up in a foetal position. It is heartbreaking to die at such an age, in such a way . . .

Albert does not know what comes over him, but instinctively he grabs the old man’s shoulder and heaves. The dead man topples over and lands heavily on his belly. It takes several seconds for the penny to drop. Then suddenly the truth is glaringly obvious: when a man is advancing towards the enemy, he does not die from two bullets in his back.

Albert steps over the body and takes a few paces, he is still half crouching though he does not know why, since a bullet can strike whether a man is standing or stooping, but instinctively he offers as small a target as possible, as though war were constantly waged for fear the sky should fall. Now he stands before the body of young Louis. The boy’s hands, clenched into fists, are pressed against his mouth and in this pose he seems so young; he is barely twenty-two. Albert cannot see his face, which is caked in mud. He can see only the boy’s back. One bullet wound. With the two bullets in the old man, that makes three. And only three shots were fired.

As he straightens up again, Albert is still shaken by what he has discovered. By what it means. A few days from armistice, the lads were in no hurry to take on the Boche, the only way to goad them into an attack was to start a fight: so where was Pradelle when these two men were shot in the back?

Dear God . . .

Shocked by the realisation, Albert turns and sees Lieutenant Pradelle bearing down on him, moving as fast as his heavy kit will allow, his head held high. What Albert most notices is the lieutenant’s stare, his bright, cold eyes. He is utterly single-minded. Suddenly, the whole story becomes clear.

It is at that moment that Albert realises he is going to die.

He tries to move, but everything in him refuses to obey: his mind, his legs, everything. Everything is happening too quickly. As I said, Albert was never a man in a hurry. In three swift strides, Pradelle is upon him. Next to them is a gaping hole, a crater made by a shell. The lieutenant’s shoulder hits Albert square in the chest, winding him. He loses his footing, tries to stop himself but falls back, arms spread, into the void.

And, as he falls into the crump-hole, as though in slow-motion, he sees Pradelle take a step back, and in his expression Albert sees the extent of his defiance, his conviction and his provocation.

Albert rolls as he hits the bottom of the crater, his momentum barely slowed by his kit. His legs become tangled with his rifle but he manages to struggle to his feet and quickly presses himself against the muddy slope as though ducking behind a door for fear of being surprised. Leaning his weight on his heels (the compacted clay is slippery as soap), he tries to catch his breath. His fleeting, tangled thoughts keep returning to the cold, hard look in Pradelle’s eyes. Up above, the battle seems to have intensified, the sky is strung with garlands of smoke. The milky sky is lit by blue and orange haloes. The shells fired from both sides rain down as they did at the Battle of Gravelotte2 in a deafening thunder of whistles and explosions. Albert looks up. There, standing on a ledge, overhanging the crater like the angel of death, he sees the silhouette of Lieutenant Pradelle.

To Albert, it seems as though he spent a long time falling. In fact, barely two metres separate the men. Probably less. But it makes all the difference. Lieutenant Pradelle stands above, feet apart, his hands firmly gripping his belt. Behind him, the flickering glow of battle. Calm, motionless, he looks down into the hole. He stares at Albert, a half-smile playing on his lips. He will not lift a finger to help him out. Albert is shocked, he sees red, he grabs his rifle, stumbles but manages to right himself, raises the weapon and suddenly there is no-one standing on the edge of the pit. Pradelle has disappeared.

Albert is alone.

He drops the rifle and tries to get his second wind. He cannot afford to waste time, he should scrabble up the side of the crater and run after Pradelle, shoot him in the back, grab him by the throat. Or find the others, talk to them, scream at them, do something, though he does not know what. But he feels so tired. Exhaustion has finally overtaken him. Because this is all so stupid. It is as though he has just set down his suitcase, as though he has arrived. He could not climb the slope even if he wanted. He was within a hair’s breadth of surviving the war, and now here he is at the bottom of a shell crater. He slumps rather than sits and takes his head in his hands. He tries to assess the situation, but his confidence has suddenly melted away. Like an ice cream. Like the lemon sorbets Cécile loves, so sour that she clenches her teeth and screws her face up in a catlike expression that makes Albert want to hug her. When was it that he last had a letter from Cécile? This is another reason for his exhaustion. He does not talk about it to anyone, but Cécile’s letters have dwindled to brief notes. With the end of the war in sight, she writes as though it were already over, as though there is no longer any point in writing long letters. It is not the same for those who have whole families, who are constantly getting letters, but for Albert there is only Cécile . . . There is his mother, too, of course, but she is more tiresome than anything else. Her letters have the same hectoring tone as her conversation, as she tries to make his decisions for him. These things have been wearing Albert down, eating away at him; and then there are all his comrades who have died, the fallen friends he tries not to think about too much. He has experienced them before, these moments of abject despair, but this one comes at a bad time. Just when he needs to summon all his strength. He could not say why, but something inside him has suddenly given way. He can feel it in his belly. It is a vast weariness, as heavy as stone. A stubborn refusal, something utterly passive and detached. Like the end of something. When he first enlisted and, like so many men, tried to imagine what war would be like, he secretly thought that, if the worst came to the worst, he would simply play dead. He would collapse or, for the sake of credibility, he could scream and pretend he had just taken a bullet through the heart. Then all he would need to do was lie there and wait until all was calm again. When it was dark, he would inch towards the body of a fallen comrade, someone who was really dead, and steal his papers. After that, he could continue his reptilian crawl for hours on end, stopping and holding his breath whenever he heard voices in the darkness. Taking a thousand precautions, he would carry on until he came to a road and he would head north (or south, depending). As he trudged, he would learn the details of his new identity by heart. Then he would fall in with a lost unit, whose caporal-chef, a heavyset man with . . . As you can see, for a bank teller Albert has a vivid imagination. Perhaps he was influenced by Mme Maillard’s flights of fancy. In the beginning, this romantic vision of warfare was one he shared with many of his comrades. He would imagine serried ranks of soldiers in their striking blue and red uniforms marching towards the terrified enemy. Their fixed bayonets would sparkle in the sunshine as the plumes of smoke from a few carefully aimed shells confirmed the enemy had been routed. In his heart, Albert had signed up for a war from the pages of Stendhal only to be confronted by a banal, barbaric slaughter which claimed a thousand lives a day for fifty months. To get a sense of the carnage, one had only to peer out over the lip of a trench and survey the scene: a wasteland devoid of any plants, pockmarked by thousands of craters, littered with hundreds of rotting corpses exuding a putrid stench that made your stomach lurch again and again. At every lull in the fighting, rats as large as hares would scurry hungrily from one corpse to another, fighting the blowflies for the worm-eaten remains. Albert knew all this, because he had served as a stretcher-bearer at the Battle of the Aisne and, when he could find no more wounded men whimpering or howling, he collected bodies in various stages of decomposition. He knew everything there was to know. It was a difficult task for Albert who had always been tender-hearted.

And, to put the tin hat on the misfortunes of a man who is about to be buried alive, Albert is a little claustrophobic.

As a child, the very thought that his mother might inadvertently close the bedroom door after she said goodnight had made him feel sick. He would simply lie there, he never said anything, he did not want to trouble his mother who was always telling him she had troubles enough already. But the night and the darkness frightened him. Even quite recently, when he and Cécile were rolling around in the sheets, whenever Albert was completely covered, he found it difficult to breathe and felt a panic rising in him. Especially since Cécile would sometime wind her legs around him and hold him there. Just to see, she would say with a laugh. Suffocation is the form of death he most fears. Fortunately, he is not thinking about this because next to what is about to happen, being trapped between Cécile’s silken thighs will seem like paradise. If he knew what lay in store, Albert would want to die.

Which would not necessarily be a bad thing, since that is what is going to happen. Though not just yet. In a little while, when the fateful shell explodes a few metres from his shelter, raising up a wave of earth as high as a wall which will collapse and cover him completely, he will not have long to live, but it will be just long enough to realise what is happening to him. Albert will be seized by that desperate desire to survive, a primitive resistance of the sort that laboratory rats must feel when picked up by their hind paws, or pigs about to have their throats cut, or cattle about to be slaughtered . . . We will have to wait a while before this happens . . . Wait for his lungs to blench as they gasp for air, for his body to tire of his desperate attempts to free himself, for his head to feel as though it will explode, for his mind to be engulfed by madness, for . . . let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Albert turns and looks up for a last time; it is not very far when he thinks about it, it is simply too far for him. He tries to summon his strength, to focus on nothing but scrabbling up this slope, getting out of this hole. He picks up his kitbag and his rifle, steels himself and begins to climb. It is not easy. His feet slip and slide in the mud, he can get no purchase; he digs his fingers into the clay, lashes out with the toe of his boot trying to create a foothold, only to fall back. So he drops his rifle and his kitbag. If he had to strip naked, he would not hesitate. He presses himself against the muddy hill and begins to crawl on his belly, his movements are like those of a squirrel in a cage, he scrabbles at the empty air, falls and lands in the very same spot. He pants, he groans and then he howls. Panic is getting the better of him. He can feel tears welling, he beats his fists against the wall of earth. The edge of the crater is almost within reach, for Christ’s sake, when he extends his arms he can almost touch it, but the soles of his boots skid and every centimetre he gains is just as quickly lost. I have to get out of this fucking crump-hole! he screams to himself. And he will do it. He is prepared to die, some day, but not now, it would be too stupid, too senseless. He will get out of here and hunt down Lieutenant Pradelle, he will go looking in the German trenches if necessary, he will find him and he will kill him. It gives him courage, the thought of gunning that fucker down.

For a moment he ponders the miserable notion that, despite trying for more than four years, the Boche have failed to kill him; it is a French officer who will do the job.

Shit.

Albert kneels and opens his pack. He takes everything out, slips his canteen between his legs; he will spread his greatcoat over the slippery slope and dig anything and everything that might serve as a crampon into the sodden earth; he turns and at precisely that moment he hears the whine of the shell above him. Suddenly worried, Albert looks up. In his four years at the front he has learned to tell a 75mm shell from a 95mm, a 105mm from a 120mm . . . This time he hesitates. Perhaps because of the depth of the crater, or perhaps because of the distance, it is heralded by a strange, new sound

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...