- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Heiress Prudence MacKenzie and ex-Pinkerton Geoffrey Hunter are about to become more than partners as investigators—they are to be wed at Trinity Church in Lower Manhattan. But a killer has designs on ruining the wedding as well as their lives . . .

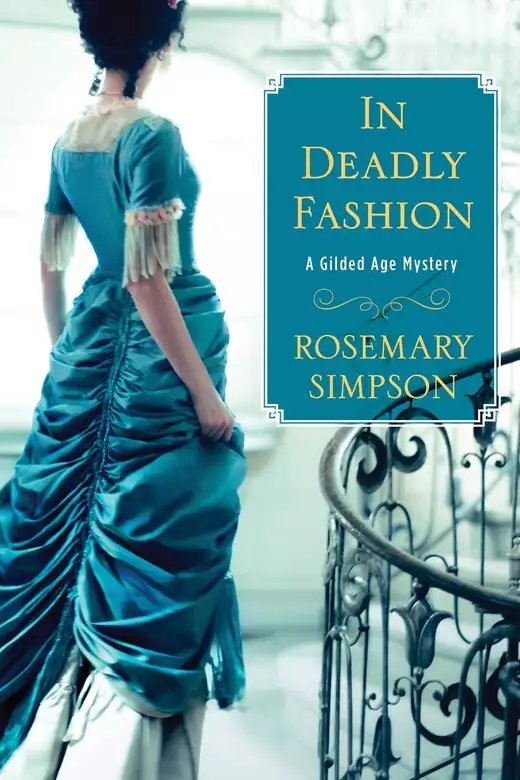

IN DEADLY FASHION

AUGUST 1891. Prudence has her heart set on wearing her mother’s wedding gown on the happy day, but she soon discovers the material has deteriorated so badly that it cannot be refurbished. With time running out, she decides to seek out a new American designer, a woman who trained in the House of Worth, the makers of the original dress in Paris, who now has a shop in New York City.

The gown is nearly complete when the expert seamstress overseeing the project is found dead in the studio, with Prudence’s wedding dress slashed to ribbons and scattered over the body. The murder incites a scandal, as client after client deserts the now struggling designer. Now not only must Prudence find the murderer, she must rescue the talented young couturière’s reputation—all while another gown is being hastily sewn.

The police suspect the seamstress’s disgruntled lover. Prudence wonders about other designers competing in the cutthroat world of high fashion. But when additional wedding plans start to go awry, it’s clear there is an elaborate campaign of sabotage and that either Prudence or Geoffrey or both are being targeted.

Once again they must work as a team to expose whoever is determined to ruin their lives—before the future they’ve so long dreamed of is left in tatters . . .

Release date: October 28, 2025

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

In Deadly Fashion

Rosemary Simpson

Josiah Gregory had reserved the church, seen to the invitations, approved the music and the flowers, hired a photographer, and selected the luncheon menu at Delmonico’s. He’d also booked for Mr. and Mrs. Geoffrey Hunter a luxurious suite aboard one of the White Star Line’s fastest oceangoing vessels. Except for the dress she would wear when she walked down the aisle of Trinity Church, Prudence MacKenzie had turned all the planning and decision-making over to her and Geoffrey’s highly organized company secretary. Josiah would see to it that every element was perfect.

He had assured them that the September 16th date would allow for a long honeymoon visiting European capitals and sailing on the Mediterranean before returning to London for Christmas with Prudence’s aunt Gillian, Dowager Viscountess Rotherton. At which time they could expect to be presented to the Prince of Wales and lavishly entertained by Lady Rotherton’s titled friends. Luncheons, dinners, balls, nights at the opera and the theater. Stalking on someone’s estate. Perhaps even a trip to Scotland, though winter weather in the north was nothing to look forward to. The secretary had done his research.

“Josiah wants us to go over all the lists one more time.” Prudence nibbled on her toast and sipped at her coffee.

“Does it matter? We know there won’t be anything to add or change.” Geoffrey leaned across the dining room table to kiss her lightly on the forehead, thinking how beautiful she looked in the early morning hours. How perfectly the black equestrian habit she was wearing flattered her slender figure, light brown hair, gray eyes, and pale skin.

“His feelings will be hurt if we don’t.” She handed her fiancé a sheaf of papers covered with Josiah’s perfect penmanship. “You don’t have to read them. Just put your initials at the bottom of each page. Scribble something appreciative, like Well done! He’s put so much time and energy into this. I don’t know how we would have managed without him.”

“I should have taken you up on your suggestion that we get married by a justice of the peace.” Geoffrey scrawled a few words on each page, initialed all of them, and considered it a task duly completed.

“I’m glad you talked me out of it,” Prudence said. She took for granted her assured place among New York City’s wealthy social elite, and seldom bothered to worry about following the inflexible customs demanded by that high and exclusive society. But Geoffrey and Josiah had been right to insist that a wedding was not something to be dismissed. She’d been so focused on negotiating the terms of a contract she’d been drafting—her first commission as a member of the New York State Bar—that she’d been willing and eager to push everything else aside. Even an event as momentous and life-changing as her own nuptials. She really would have to find exactly the right words with which to thank Josiah for all he’d done.

“The carriage has pulled up out front, Miss Prudence,” announced Cameron, the MacKenzie family butler hired long ago by the late Judge MacKenzie, Prudence’s father. Tall, with the posture of a soldier on parade, not a hair or a thread out of place, Cameron had seen to the efficient running of the household since before his current employer was born. He thoroughly approved of Geoffrey Hunter, especially since Miss Prudence had a habit of getting herself into situations from which she had to be extricated before serious harm was done. Hunter was educated, financially well-off, the scion of a distinguished Southern family, and an ex-Pinkerton agent. Ideal husband material for the young woman the butler loved as though she were his own daughter.

Cameron smiled to himself as he stepped into the hallway and Prudence gathered her veiled riding hat, gloves, and crop from where she’d tossed them onto the table. Ladylike restraint had never been a lesson easily learned. She tended to walk too quickly, say almost exactly what she meant instead of what she should, and do without a corset when she thought she could get away with it. She’d taken up detecting and the law, neither of which were suitable activities for a female of her station, and she was as close to being a magnet for danger as a human being could get. He wondered if becoming Mrs. Geoffrey Hunter—and eventual motherhood—would have any calming influence on her at all. Probably not.

Prudence and Geoffrey had gotten in the habit lately of riding in Central Park several times a week, less for the New York convention of being seen in the right place at the right time than because they both enjoyed the exercise. It helped that Geoffrey had been given two fine horses by a Long Island breeder whose case he had argued in open court. Until they married, Geoffrey would continue to live and take most of his meals at the Fifth Avenue Hotel, but on the mornings they didn’t meet at the stables, he joined Prudence for coffee and conversation before her carriage took them to the park.

“I’ve got to stop by Madame Régine’s salon on the way,” Prudence said. “Do you want to check on the progress the contractors are making upstairs before we go?” Geoffrey had it in mind to build a large mansion of their own on Fifth Avenue sometime in the next few years, but for the foreseeable future they’d agreed to live in Prudence’s family home on the corner of Fifth Avenue and Twelfth Street. The rooms that had once belonged to her parents and then to Prudence’s father and his second wife—of bitter memory—were being refurbished to suit the more modern tastes of the soon-to-be-married younger couple.

“All I really want to know is whether they’re on schedule.” Geoffrey folded that day’s Times and slipped it into the lawyer’s leather briefcase he carried with him everywhere he went. His meticulous attention to the legal details of the cases he undertook was what made him one of the most sought-after attorneys and private inquiry agents in the city. He’d learned to pace himself, but there were days when every spare minute was given over to reading briefs and studying investigative reports.

“We’ve a meeting with the architect and the builder later on this afternoon,” Prudence reminded him. “Cameron says that judging by the number of workers in the house and the noise from the second floor, things seem to be moving along pretty much as promised. That’s a bit of a miracle, given all the construction going on in the city. Are you ready?”

“Isn’t it too early in the morning for a fitting?” Geoffrey had learned a great deal about women’s couture in the past few months. If it wasn’t Prudence giving him updates on the all-important wedding gown, it was Josiah tut-tutting over the difficulty of scheduling appointments for a society belle who refused to act like one.

Prudence opened a blue velvet jewelry box that had sat beside her riding gear. “My mother wore these,” she said, lifting out a triple strand of perfectly matched pearls. “The bodice of the wedding gown will have pearls sewn on in a waterfall pattern, and there will be more pearls on the sleeves and the skirt. Madame Régine needs to be able to match the color of the pearls her seamstresses will be using to the necklace.”

“They’re white,” Geoffrey said, as if that solved the problem.

“Do you have any idea how many shades of white pearls can be?” Prudence asked, only half-seriously.

“I give up. We’ll tell Kincaid to stop by Madame Régine’s on the way to the stables. Are you sure someone will be there?”

“Positive. Madame Régine herself is meeting me. She’ll put the pearls in her safe after the head seamstress has found a match for them.”

It was something of a minor scandal that Prudence MacKenzie’s wedding gown was not being designed by Charles Frederick Worth’s Paris salon. Lady Rotherton had telegrammed her shock at the news that an upstart, no-name American woman—of all things—had been chosen to create the most important dress her niece would ever wear. And which would be described in minute detail by the New York Times and every society rag worth its name. She’d followed the telegram with a letter that Prudence had skimmed, then refolded and returned to its envelope. With a chuckle. Aunt Gillian could always be counted on to volunteer her opinion, even when it hadn’t been asked. She’d apparently forgotten that she, too, had once been called an upstart American—whose father had bought her a title.

The truth was that the gown Prudence had originally intended wearing had been created by the House of Worth, lovingly stored away the day after Sarah Vandergrift married Thomas Pickering MacKenzie. It hadn’t occurred to Prudence that the carefully preserved dress would have deteriorated so much over time that there was no possibility of restoring it. Preoccupied with the theatrical rights contract she was negotiating between her friend Lydia Truitt and the Broadway impresario David Belasco, Prudence had left the matter of the dress too late. A hasty trip to Paris was out of the question. Even Charles Frederick Worth’s celebrated couture house could not perform miracles.

It was Josiah who came to the rescue. One of his many theatrical costumer friends knew of a young dress designer who’d trained in the House of Worth and recently come to New York to open her own salon, an almost unheard-of enterprise for a woman. Females sewed for a living, adapted fashionable patterns to the figures of their clients, and operated small, boutique operations. They did not challenge the male world of high fashion and salons that boasted palatial reception rooms and squads of seamstresses adept at the art of fine beadwork and exquisite embroidery.

To make things worse, Madame Régine wasn’t even French. She was a relatively recent American whose deceased parents had immigrated from Ireland to the tenements of the Lower East Side. How she got to the House of Worth was a mystery best not looked into. But she was back in America now, ambitious, talented, and determined to make her way in a field where success depended on the fickle whims of women who had never soiled their fingers with work of any kind. For an independent individual like Prudence MacKenzie, Madame Régine was the perfect choice.

She was honest, too.

“My name is really Regina Healy,” she told Prudence at their first meeting. “But while I was at the House of Worth in Paris, everyone called me Régine—and it stuck.”

Her French was impeccable and her English without a discernible Irish accent. She’d made herself over to better take on the world she was bent on conquering. Régine had learned who was who in New York City: who was important and might be persuaded to frequent her salon, who unapproachable and therefore not worth the trouble.

And she’d heard the story of the frequently gossiped about society girl who’d become a private investigator and then had the gall to sit for and pass the New York State Bar exam.

When Prudence recounted the tale of her mother’s unsalvageable wedding dress and described what she wanted in its place, Régine sketched a gown that left her new client breathless.

“How did you do that?” Prudence asked, touching the drawing paper with an admiring finger, careful not to smudge a single line. “It’s exactly how I imagined it would look.”

“Not quite,” Régine said. “You’ll want small changes here and there as we work on it. Trust me, there’s a huge difference between what you see on paper and how a gown looks when a fabric has been chosen.”

“Silk?” Prudence asked.

“The finest silk we can find,” Régine agreed. “We’ll decide on the thickness once we see how the various types of silk fold.”

“We don’t have much time,” Prudence reminded her.

“Then it’s fortunate I don’t have many clients yet.”

Both women had burst into spontaneous laughter.

“I’ll wait in the carriage,” Geoffrey decided, handing Prudence onto the pavement in front of Madame Régine’s salon. He looked admiringly at what had once been a substantial family home constructed of square cut gray stone, transformed now into a dignified business venture with a discreet brass plaque beside the shiny black front door. “I thought you said she was just starting out. This looks as though someone has sunk a very decent amount of money into the enterprise.”

“It does, doesn’t it?” Prudence agreed. “And it’s even more impressive inside. Turkish carpets, heavy velvet drapes, furniture that may not be but certainly looks antique. I’d say it’s on par with anything to be found in Paris.”

“I forgot that you and Lady Rotherton have been to House of Worth more than a few times.”

“She more than I. She goes over at least once a year. Monsieur Worth keeps all the measurements of his clients in files that he stores in a locked vault. As long as a lady doesn’t change her figure too drastically, it’s not always necessary to be fitted on the premises.”

“I’ll ring the bell for you.” Geoffrey extended his arm, assisted Prudence up the stone steps, and pressed a gloved finger on the recessed doorbell beside the brass plaque. He waited, half turned to go back to the carriage, then frowned as the door remained closed. No sound of anyone approaching from inside. “I thought you said Madame Régine was meeting you here.”

“We may be a few minutes early.” Prudence looked in both directions along the empty street, then nodded as a hansom cab turned the corner from Fifth Avenue. “There she is. Right on time.”

The woman who descended from the hansom cab was strikingly beautiful. Taller than average, with shining black hair, dark blue eyes, and skin as pale as the pearls Prudence had shown Geoffrey that morning. She was impeccably dressed in the latest Parisian style, but with a certain distinctive difference that would draw every woman’s attention. It was a graceful elegance that Madame Régine sought to impart to each of her creations, what she thought of as her signature panache. Impossible to quantify or explain, but unforgettable in its élan.

“Brenda Leavitt should be here,” Madame Régine said after being introduced to Geoffrey, who stood to one side as she produced a key from her reticule and inserted it into the lock. “If she’s all the way in the back sewing room, she may not have heard the bell.” The door swung open on a dark hallway. “That’s odd. I would have thought she’d have turned on the gaslights. She knows what time we planned to be here. I reminded her yesterday. Will you join us, Mr. Hunter?”

Even before Madame Régine’s invitation, something about the darkness of the salon’s interior and its utter stillness had made Geoffrey decide not to wait in the carriage after all. He didn’t really expect anything to be amiss, other, perhaps, than a seamstress who had overslept and failed to arrive on time. But Prudence had a way of walking into trouble that made him conclude it might be better if he did not leave the ladies alone.

“Straight through along this hallway,” Madame Régine directed. “The workrooms are upstairs, for the light. I had all the rear wall windows replaced and enlarged. Gaslight isn’t always bright enough for the most delicate work.”

She started to call out Brenda Leavitt’s name, but Geoffrey shook his head. Their own footsteps were the only sounds in the building.

Geoffrey heard a scrabbling sound behind him. Prudence had opened her reticule and was reaching inside it for the two-shot derringer he insisted she always carry. She, too, had picked up on the vague sense of wrongness that seemed to permeate the building like a bad smell.

“The fitting rooms are along here, to the left,” Madame Régine said. “But I told Brenda we’d meet in my office. I want to put your pearls into the safe right away, as soon as we’ve matched them with one of ours. Then you can be on your way to the park.”

“I shouldn’t have suggested we do it this way,” Prudence apologized. “It seemed logical at the moment when we planned it, but I’m beginning to think it was a bad idea. I could just have easily made time during the day to bring the pearls by, and you wouldn’t have had to go to this extra bother.”

“It’s no trouble.” Madame Régine was used to catering to the odd whims of her clients. It was part of keeping their business.

The door to her private office was closed and locked.

“Brenda isn’t here yet,” Madame Régine said. “She would have opened for us if she were.”

“Your head seamstress has a master key, including one that opens your office?” Geoffrey asked. His question made it clear he considered that type of arrangement less than trustworthy.

“Not usually. But I gave her a copy of my office key yesterday. I didn’t want to keep you waiting in case I was late.”

“If she’s here, where would she be?” Prudence asked. She’d been to several fittings with Brenda Leavitt, who had never been late to a single one of them.

“She could be upstairs, in the workroom where the gowns that are nearly finished are stored in individual wardrobes overnight,” Madame Régine said. “She might be getting a piece of the fabric to bring down with her so we can see the effect of your pearls and ours against the silk.” Logical, but she sounded dubious.

“Shall we?” Geoffrey asked.

Madame Régine led the way to the employee staircase that opened onto an enormous second-floor sewing room with floor-to-ceiling windows and worktables in orderly ranks throughout the space. All of the finer work was done by hand, but there were sewing machines for hidden seams and the creation of muslin patterns. Six of them, shrouded in canvas covers to keep the needles and surfaces dust free. At the far end of the room stood a row of cedar-lined wardrobes, each one labeled with a client’s name.

“Brenda? Are you here?” Madame Régine’s voice echoed through the vast space. She stood in the doorway, Prudence and Geoffrey beside and a little behind her. It was a moment before she stepped over the sill, as if even before she saw the disaster, she had become afraid of what she would find. “Brenda?”

A woman’s body lay face down on the floor. Blood so fresh it was still bright red and liquid spattered her back, the floor, and the legs of the sewing machine she must have been trying to get behind. She had been bludgeoned multiple times, the splintered shards of her skull clearly visible through the tangled mass of her hair. Beside her lay one of the heavy glass weights used to secure fabric to the surface of the cutting table. Smears of blood, hair, and brain identified it as the murder weapon.

Someone strong had attacked her, had chased her halfway across the workroom, battering repeatedly at her head and body as she tried to escape and finally fell.

Atop the body and scattered all around it were ribbons of white silk. A snowstorm of white floating in a pond of scarlet.

A name was embroidered on a fabric label the killer had positioned just above the dead woman’s waist.

“My dress,” whispered Prudence, unable to tear her eyes away from what she was seeing. “Cut into pieces and tossed over her as she lay dying. The poor woman. Who would do such a thing?”

“If that’s Brenda Leavitt, she’s the chance victim here.” Geoffrey turned Prudence away from the scene, holding her closely against him, pressing her face against his chest, stroking her back to quiet the trembling he could feel running up and down her spine. “The real target was you, my love.”

And by her sobbing, he knew Prudence believed him.

Detectives Stephen Phelan and his younger partner, Pat Corcoran, were assigned to the dressmaker case, as it was called around the Mulberry Street Station House.

Not until they arrived at Madame Régine’s salon did Phelan discover that the victim had been sewing a wedding gown for the annoying young socialite turned amateur inquiry agent, Prudence MacKenzie. Phelan had no patience with women edging their way into professions properly reserved for men. He’d more than once had to choke back what he would have liked to say to the late Judge MacKenzie’s daughter. She had an infuriating way of turning up before him at a murder site, always accompanied by the ex-Pink Southerner she was now about to marry.

The bride-to-be, decked out in an expensive riding habit and sipping a cup of tea in Madame Régine’s private office, glanced at him as though she and her intended had already taken charge of the crime scene. Phelan felt his ears flush red. Geoffrey Hunter was an experienced investigator—and a man. But he was also wealthier than Phelan could ever hope to be and welcomed by virtue of his birth into a society that would forever exclude an Irish copper. Phelan loathed both of them. He’d promised himself that one day he’d teach them what it felt like to be a working man in this city.

“Detective Phelan.” Geoffrey Hunter rose to his feet and extended a gentlemanly hand. “I wondered if you and Detective Corcoran would be here this morning. Have you been filled in on the details of what’s happened?”

“I have. You and Miss MacKenzie will remain here until I’m ready to question you. Madame Régine will come with me.” Phelan acknowledged Prudence’s presence with a stiff nod; that was as much as he was willing to concede to the bare bones of civility.

“We were together, the three of us, when we found Brenda Leavitt in the workroom,” Madame Régine protested. “We’ve been in one another’s company ever since arriving. I met Miss MacKenzie and Mr. Hunter on the front steps and led them inside. I don’t understand why you think you have to separate us.”

Another woman attempting to dictate terms of behavior to a man whose instructions she should follow without question. Phelan didn’t bother arguing with her. It was beneath him to explain the rules for interrogating suspects that Chief Thomas Byrnes insisted all of his detectives follow. Strictly speaking, the ex-Pink and the MacKenzie woman should also be kept apart, but Phelan knew he didn’t have enough uniforms assigned to the case to accomplish that.

“Out into the hallway,” he snapped at Madame Régine. He consulted the small notebook in which he kept his case notes. “The building is deeded to a Regina Healy. I assume that’s your real name?”

“I’m known professionally as Madame Régine. That’s how I would prefer to be addressed.”

“Step outside, Miss Healy.” He wasn’t going to yield anything. “I’m putting an officer on the door, Mr. Hunter. Don’t try to leave this room for any reason. That goes for Miss MacKenzie, too.” Phelan held out his hand for the ring of keys Madame Régine wore at her waist, locked the office door from the outside, and gave instructions to the beefy young policemen he stationed there. “Remember, they don’t come out no matter what.”

“Yes, sir.”

“All right, Miss Regina Healy, take me to this workroom where you found the body.” Phelan toyed for a moment with a pair of handcuffs, letting them dangle from one finger. “Do I need to use these?”

Madame Régine’s eyes blazed with a fury she was barely able to contain. The handcuffs looked as though the cold steel would dig into her skin, and she had no doubt that the detective would not be gentle as he fastened them around her wrists. She’d learned the hard way—as most tenement dwellers did—that arguing with a policeman would get her nowhere. She was years away from that hardscrabble childhood, but she’d never forgotten the lessons of the past. Do whatever they tell you when you have no other choice.

“I don’t suppose we’re going to leave this case in Detective Phelan’s less-than-capable hands.” Prudence had set down her empty teacup and found paper and pencil in Madame Régine’s desk. “I might as well write down everything we saw and can remember. It looks as though we’ll be stuck here for a while with nothing better to do.”

She frowned in concentration, covering the piece of embossed letter paper with line after line of perfect penmanship, the product of hours of practice under the tutelage of demanding governesses. Every now and then she paused, tapped the pencil on the desk, and asked Geoffrey a question. It wasn’t that she didn’t trust her own memory, but Prudence was aware that despite everything her partner had taught her, she couldn’t match his ability to read a scene and draw logical conclusions. That came only after years of experience.

“Would a glass weight like the one used on the seamstress be left out on the cutting table overnight?” Geoffrey asked. He nodded approvingly as Prudence sketched the weight from memory. Neither of them had touched or moved it, but both had memorized what it looked like and the spot where it lay.

“When I was working in the costume shop at the Argosy Theatre the cutting table was always cleared at the end of the day.” Prudence absentmindedly rubbed the healed but still sensitive palm of one hand. She’d gone undercover on the Argosy Theatre case and been badly injured. “Once in a while a weight would be forgotten, but they were usually kept in a basket under the table. The fabric shears—like the one Brenda Leavitt’s killer used to destroy my dress—were stored in a locked drawer because they’re much more expensive than ordinary scissors. The costume mistress said they should never be used on anything but material. Cutting paper or cardboard with them was a cardinal sin. Don’t ask me exactly why. It has something to do with the way the blades are sharpened.”

“That answers one of my questions. Our killer came unarmed. He would have used a gun if he’d had one. Instead, when his victim ran from him, he picked up the only weapon at hand—a glass weight in plain sight on the cutting table—and chased her across the room. He was bigger, stronger, and faster than Brenda Leavitt, but it couldn’t have been a swift or painless death.”

“If, as Madame Régine suggested, Brenda had come upstairs to get a piece of silk to match with the pearls, she probably unlocked whatever drawer the fabric shears were kept in. They weren’t on the cutting table or her attacker would have used them instead of the glass weight.” Prudence was reenacting the death scene in her mind. Just as Geoffrey had taught her. Placing herself there as an imaginary witness. “I don’t think a knife could have made those even cuts in the silk. It would have slashed raggedly through the fabric.”

“So perhaps Brenda had already cut a piece of the silk, then set the shears down somewhere out of the killer’s sight. She ran because she was trying to get to them to defend herself.” Knives were common street weapons. Odd that this intruder apparently carried neither a gun nor a blade.

“Except for the glass weight, there was no other weapon anywhere near the body,” Prudence said.

“Master chefs take their personal knives with them to whatever restaurant they work in,” Geoffrey mused. “Would a seamstress have bought her own fabric shears?” He wasn’t sure where he was going with the question, but he was puzzled by the absence of shears that had clearly been used to shower the dead woman with remnants of the garment she’d been working on. Some killers were known to collect souvenirs of their crimes. Personal objects belonging to their victims.

“They’re too expensive,” Prudence said. “If a salon de couture operates at all like the costume shop at the Argosy, the seamstresses are provided what they need. They’re not paid enough to be able to invest in the kind of high-priced shears needed to cut silk, velvet, and satin.”

“So if the shears weren’t left behind, it was because whoever took them knew their monetary value or prized them as a keepsake.”

“There’s another way to look at this,” Prudence said. “If it was someone who was familiar with the way a salon’s sewing room is organized, the killer might have already been here, perhaps was in the act of destroying the dress, when Brenda Leavitt discovered him. He might have dropped the shears or she snatched them out of his hand and threatened to call the police. The weight was close by, so he picked it up. She ran. If she was holding the shears in one hand, they could have fallen under her body when she went down. The dress was already . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...