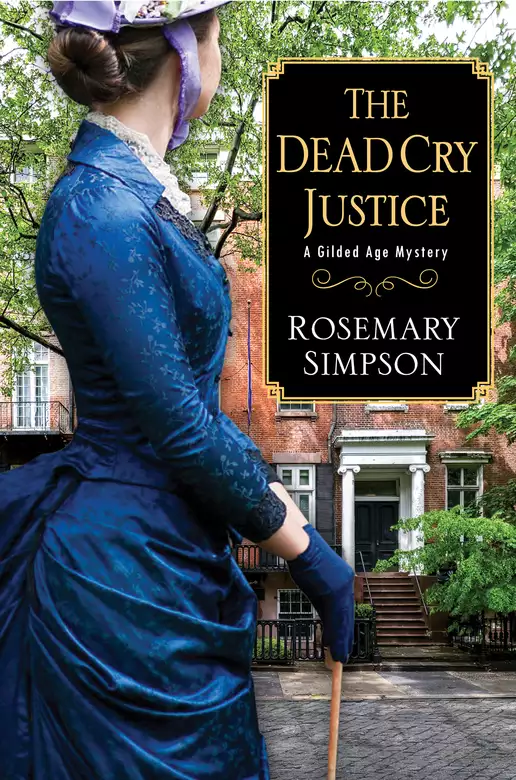

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

May 1890: As NYU Law School finally agrees to admit female law students, Judge MacKenzie's daughter Prudence weighs her choices carefully. Chief among her concerns is how her decision would affect the Hunter and MacKenzie Investigative Law agency and her professional and personal relationship with the partner who is currently recuperating from a near fatal shooting.

But an even more pressing issue presents itself in the form of a street urchin, whose act of petty theft inadvertently leads Prudence to a badly beaten girl he is protecting. Fearing for the girl's life, Prudence rushes her to the Friends Refuge for the Sick Poor, run by the compassionate Charity Sloan. When the boy and girl slip out of their care and run away, Prudence suspects they are fleeing a dangerous predator and is desperate to find them.

Aided by the photographer and social reformer Jacob Riis and the famous journalist Nellie Bly, Prudence and Geoffrey scour the tenements and brothels of Five Points. Their only clue is a mysterious doll with an odd resemblance to the missing girl. But as the destitute orphans they encounter whisper the nickname of the killer who stalks them—Il diavolo—Prudence and Geoffrey must race against time to find the missing children before their merciless enemies do . . .

Release date: November 30, 2021

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Dead Cry Justice

Rosemary Simpson

A packet of sandwiches wrapped in butcher paper and brown twine lay on the bench beside her; an enormous red-gold dog stretched its shaggy length at her feet. Nesting birds darted in and out of the tree canopies and a riot of early wildflowers lined the gravel paths and dotted the open spaces where the warm May weather had turned the grass a brilliant green. Everything in this pastoral retreat at the bottom of Fifth Avenue was alive with new purpose.

Except Prudence.

She sighed, rubbed the sole of one booted foot over Blossom’s thick, feathery coat, reached absentmindedly for the sandwiches, then let her hand drop to her lap. She wasn’t hungry.

Her eyes drifted over a group of well-dressed young men entering the Gothic main entrance of the fifty-year-old building that housed the Law School of the University of the City of New York. For a moment, she imagined herself one of them, laughing and talking about nothing in particular as they climbed its marble steps and disappeared into narrow corridors lined with lecture halls.

On a long-ago outing with her father, she’d listened from one of those same hallways to the resonant voice of a bearded, solemn-faced professor booming off the walls of a wood-paneled amphitheater. As student after student stammered answers the lecturer unabashedly ridiculed as incomplete, illogical, or preposterously wrong, Judge MacKenzie’s arm had tightened reassuringly around his daughter’s shoulder. Even at fifteen years of age Prudence could have held her own with the learned men of the law who had no patience with ineptitude. But at the time of that visit, no woman had as yet been called to the bar in New York State.

Four days ago, on May 5, 1890, the university’s governing council had met and voted to admit women to the study of law. One of the councillors had sent a note to Prudence’s Fifth Avenue home, politely requesting a few minutes of her time, writing that he had been her father’s friend and colleague from the years before she was born. She’d invited him to tea.

“We need this class of women to succeed,” he’d explained between bites of Cook’s excellent seed cake. “Already there’s opposition to our decision. Columbia’s dean is declaring to anyone who will listen that females will only be allowed to enroll in that institution over his dead body. Or words to that effect.”

“What will happen to the Woman’s Law Class?” Prudence asked, referring to a series of private seminars recently sponsored by the university. There’d been articles detailing the new venture in the Times. “I’ve heard nothing but praise for Dr. Kempin.”

“She’s a good lecturer. We wouldn’t have endorsed her otherwise. But she’s going back to the University of Zurich, and the course she’s been offering was never meant to substitute for what we demand of our matriculated male students. No admittance criteria. Forty-eight hours of instruction over a six-week period. You can’t compare that to what the law school requires.”

“I understood her students take an exam.”

“They do. But what they earn is a certificate of attendance rather than a diploma. The program of study doesn’t go beyond a bare minimum of legal issues applicable to the fair sex. Dr. Emilie Kempin may have begun by wanting to establish her own law school for women, but what she ended up with is a stopgap measure at best.”

“Thirteen states have admitted women to the bar,” Prudence reminded him gently. It was a topic she and the late Judge MacKenzie had enthusiastically followed during the years when she’d joined him in the library every evening while he recounted the details of the cases before him. “Kate Stoneman was licensed to practice in this state four years ago. Without the benefit of a law school education.”

“But no other woman in New York has followed her example,” Edgar Carleton said, brushing crumbs from his beard. “Your father told me more than once that he was confident you could pass the bar exam without ever setting foot in our classes. He said you’d apprenticed at his knee since you were big enough to lift one of his lawbooks. I believed him then, Prudence, and I believe him now.”

“There are extenuating circumstances.” She hoped he wouldn’t ask why she hadn’t followed Kate Stoneman’s example and applied to take the bar exam despite a lack of formal study.

“What happened to Mr. Hunter was in all the papers. I know he’s your partner at Hunter and MacKenzie, Investigative Law.” He pronounced the name of the firm with the gravity normally accorded only the city’s most long-established law firms. Ex-Pinkerton Geoffrey Hunter and his society-girl partner were slowly but surely gaining the grudging respect of the city’s police, newspapers, and legal community. “I also understand he’s making a slow but assured recovery from the bullets he took in February.”

“He almost died.”

Prudence heard the words as a whisper in her heart and hoped the lawyer sitting opposite had not caught the emotional edge of what had been weeks of desperate uncertainty.

Carleton sipped his tea, giving the judge’s daughter time to turn her full attention back to the argument he’d come to make. Years of teaching and practicing law followed by appointment to the university’s governing council had taught him to be wily and patient. Prudence MacKenzie had already proved to the rigid world of New York society that she could venture outside the bounds of what was considered appropriate behavior and remain a lady in fact as well as name. In his considered opinion, it was time for her to take the next step.

“We need the women of this first class to persevere through graduation. They’ll have to support each other both within the lecture halls and in the larger community. Stand their ground without flinching. I believe that calls for a strong leader to hold them together, Prudence. Someone of their own feminine persuasion because we can’t predict how the male students will receive them.”

“I’ve heard some of the stories about what happened elsewhere,” Prudence said. She grimaced. “Glue on the seats so the women’s skirts stuck to the wood, pig’s blood in their inkwells, the tallest men in the class sitting directly in front of them to obstruct their view of the lecturer. Threats whispered in the hallways, withdrawing rooms locked or filled with discarded furniture so they couldn’t answer calls of nature.” True or not, there had been rumors of more dangerous harassments, incidents even the women who suffered them were reluctant to bring out into the open.

“That kind of behavior will not happen at New York University.” Even its council members used the nickname by which the University of the City of New York had been popularly known from its inception.

“What are you asking me to do?” She thought she knew what Edgar Carleton wanted, but her father had taught her to be sure of her facts always.

“Join the other women of this groundbreaking class, Prudence. You’d be its strongest, most well-prepared member, male or female. See it through to graduation and the bar exam. Help us prove to the naysayers that our resolution to admit women is a sound one.”

There it was. The direction and acceptance she’d longed for. The choice she was now reluctant to make because she knew it would change her life forever in ways she could not predict.

“Will you think about it?”

“I will,” she promised. Her first instinct had been to refuse outright, but Judge MacKenzie’s voice in her head had counseled a more moderate course. Don’t burn your bridges, Prudence.

“May I expect an answer in a week’s time?” Carleton had asked.

And Prudence had agreed.

Blossom sighed and resettled herself, long snout pillowed on her front paws, ears alert for a command or a threat. She was a beautiful animal, intelligent and devoted to the four- and two-legged creatures among whom she lived, immensely fond of the huge white horse whose stable she shared. But like many of her ilk, she’d only ever given her whole heart to one human. Kevin Carney of the red hair and tubercular lungs. Street child. Denizen of alleyways and an unheated shed in the backyard of a brothel. Dead now. Mercifully reprieved from a suffering that had lasted far too long. She’d transferred her allegiance to the humans who’d cared for Kevin during his final days, but her heart had remained her own.

The dog welcomed the gentle rub of the woman’s boot along her back and wondered when she’d share the package of sandwiches. Blossom had a particular fancy for ham roasted with cloves and coated with honey. She was a canine with a definite sweet tooth.

Somewhere behind her, Prudence heard the whir of a rolling hoop and the ticktock tap of the stick that kept it upright. Children’s voices trilled in high falsettos as nursemaids chided and chivied them through their afternoon walk in the fresh air. Elderly couples climbed slowly down the marble steps of their elegant redbrick Greek Revival townhomes on the north side of the square, tugged along by small dogs yipping excitedly.

Newly arrived immigrants had filtered into many of the neighborhoods south of Washington Square, drifting into the park to get away from the crowded, airless tenements that crushed several families into spaces hardly large enough for one. It was said you could hear every language spoken in every country of the world if you stood long enough on a New York City street corner. Or lingered in one of its parks.

The children, the old people, and the pinch-faced newcomers eddied around the well-dressed woman and her dog. They cast curious glances but did not approach the bench on which she sat. Every now and then someone’s eye caught hers, and a smile was exchanged or the dog’s tail thumped. Prudence, lost in her thoughts, hardly noticed the silent, polite nods as her legally trained mind concentrated on the dilemma she’d come here to resolve.

Once, not too long ago, she would have leaped at the chance to study law at New York University. She’d even contemplated following Kate Stoneman’s example to take the bar without academic credentials.

Over time she’d become diverted from what had seemed a well-defined path. Her father died. Her stepmother tried to parlay Prudence’s grief and accidental addiction to laudanum into iron control of her life and fortune. Then Geoffrey Hunter had introduced her to the world of the private inquiry agent and trained her in the ways of the famed Pinkerton National Detective Agency. They’d been successful; the bar had taken a back seat to the challenge and thrill of solving crimes. Of stopping wrongdoers in their tracks. As she’d told Edgar Carleton, there were extenuating circumstances.

None so devastating as Geoffrey’s near brush with death.

It changed Prudence’s world as nothing else had done since the loss of her father. Sitting day after day beside Geoffrey’s bed in his suite at the Fifth Avenue Hotel, she’d relived over and over again the moment his bullet-ridden body crashed into hers, the helplessness and loss of hope when his blood saturated her clothing and stained her hands. She’d assisted at the kitchen table surgery that saved his life, teeth clenched against waves of nausea as she watched forceps extract deadly bits of misshapen lead from his body. Sat bolt upright through the long night of moving him by wagon and train. The threat of infection and gangrene, the specter of amputation.

And finally, when Geoffrey opened his eyes and the doctor cautiously pronounced him out of immediate danger, came the need to talk. How difficult it had been. So much had been left unsaid.

One decision had been made. Prudence’s aunt Gillian, the Dowager Viscountess Rotherton, had sailed back to London a few weeks ago without her niece. They had argued, mildly at first, then ferociously. Lady Rotherton had threatened, ordered, and finally been reduced to flattering her sister’s daughter into considering a life among England’s titled aristocracy. With her fortune, Lady Rotherton assured her, Prudence could easily marry a title. Wouldn’t she like to be a countess? A duchess?

No, Prudence told her, she wouldn’t.

What she hadn’t said was that she couldn’t bear to leave Geoffrey. Not even with nothing between them settled. Not even with the long silences that grew stiffer and more uncomfortable with every passing day. The feeling that she was waiting for something to happen was like a slowly creeping paralysis.

The offices of Hunter and MacKenzie stayed closed. Josiah Gregory’s desk remained cleared, his scarcely touched Remington typewriter covered, the telephone unplugged from the wall. Faithful secretary that he had always been, Josiah was in Geoffrey’s hotel suite when Prudence arrived in the morning and he was still there when she left every evening.

Then Edgar Carleton had invited and urged Prudence to enroll in the first New York University Law School class to admit women. The waiting was over.

A grimy, barefoot urchin in tattered shirt and ragged pants streaked across the grass, swooped within inches of the bench on which Prudence sat, and snatched up the package of sandwiches she hadn’t yet opened.

Blossom sprang to her feet before the boy managed more than a few steps beyond the reach of her jaws, but she glanced at her mistress before leaping to sink her fangs into his leg. And read a denial of permission in Prudence’s upraised hand. Blossom sat, but her body trembled with the eagerness to chase.

The two of them watched the boy zigzag his way through the people strolling the square and then scamper across the graveled space between where the grass ended and the huge University Building blocked his way.

“Now what?” Prudence asked aloud. She walked quickly to the path that snaked along the far side of the park, the dog following her, tail wagging furiously. “I can still see him, Blossom. It looks like he plans to make a run for it.” She caught herself laughing and put one hand over her eyes to shade them from the sun. “He’s disappeared. That’s impossible. I can see right down past the side of University Building into Waverly Place and there’s no sign of him. Where did he go?”

She started off at a brisk pace, the red-gold dog trotting beside and then in front of her, plumed tail stiff, muzzle stretched out to find the scent she’d caught as the boy darted past her clutching the snack she’d been anticipating.

“Not so fast, Blossom,” Prudence ordered.

The dog obediently slowed down, stopped, and turned to wait for her human to catch up.

Hand to her side to ease her tight stays, Prudence reached for Blossom’s collar and felt the large animal’s considerable weight lean against her legs. Solid, strong, reassuring.

“Shall we find him, girl? Shall we catch our little thief?” It would be a welcome distraction from what she didn’t want to think about anymore.

“My father said students rarely went into University Building’s basement, even when he was here. It’s supposed to be haunted, although I don’t know why any respectable ghost would want to hang out in damp, smelly storage rooms.”

Blossom wagged her tail.

“I think our boy has found a way in and decided he’s safer with the ghosts than out on the streets. He’s probably right.”

And there, around the corner from the park, was a set of narrow concrete steps leading down from the sidewalk to an iron door with a broken padlock hanging from its hasp. An inch of empty space separated the edge of the door from the frame, the hinge too rusty to allow it to close all the way without someone pulling it tight. A boy on the run might not have known that, might have assumed the door would slam shut behind him. Might not have waited to find out.

Blossom smelled a narrow ribbon of ham and honey wafting through the air. She whined, but quietly, so as not to alarm her prey.

“I agree,” Prudence said. “Let’s go in after him.”

Prudence pried open the heavy iron door and motioned the large dog inside, leaving a gap just wide enough to squeeze through without attracting attention from a passerby.

The cellar stretched off into unbroken darkness, but at this end of what looked to be a huge storage room filled with piled-up furniture, shafts of weak daylight filtered through a row of grimy, sidewalk-level windows. Prudence felt her way gingerly along the wall, trying not to shuffle her feet noisily on the concrete floor as she sidestepped bits of unrecognizable debris.

She made one of the hand gestures Danny Dennis had taught her. Blossom obediently fell back to walk beside her.

Inch by inch, step by step, the woman and the dog crept into blackness. Prudence could hear nothing but her soft, hesitant footsteps, her own and Blossom’s breathing. Wherever he’d disappeared to, the boy they were after had found refuge in silence. She couldn’t tell whether he was hiding nearby or had scampered deep into the bowels of the building. Feeling her way along the wall with one hand stretched out in front of her, Prudence counted on Blossom to scent danger and alert her to it by a warning growl or low bark.

She almost cried out when her extended arm struck an obstacle. It was another iron door, though not as heavy or difficult to push open as the one leading to the street. Flakes of rust showered to the floor as Prudence felt for a handle. The door opened on corroded hinges, the scrape of unoiled metal against metal setting her teeth on edge. Was the noise loud enough to alert whoever was on the other side that someone was coming?

Her eyes gradually accustomed themselves to the dimness; what had at first seemed dark as pitch resolved into a grayness not unlike a heavy winter fog. When she looked down at the damp floor, she saw the shine of pooled water, smelled mold and the ripe rottenness of decay.

She hesitated, then nodded reassuringly to herself as Blossom’s warm snout found her hand.

“All right, girl. Here we go,” she whispered as a faraway flicker of candlelight shone briefly before being shielded from view. Not snuffed out or she would have smelled a puff of smoke as the burning wick was extinguished.

Blossom growled, but when Prudence glanced at her through the gloom, she saw the dog’s ears had not flattened and her formidable fangs remained hidden. Not a warning then, not a precursor to attack. More a shared acknowledgment that what they were seeking lay not far ahead of them.

Prudence froze in place, waiting for the glimmer of candlelight to flare again, realizing as she bided her time that, like the first room through which she and Blossom had come, this larger storage space was also dimly illuminated in places by shafts of weak daylight. Small windows that looked as though they hadn’t been opened in years were set at regular intervals immediately below the ceiling, their panes sooty with layers of dust and greasy smut.

When Prudence would have taken a step, Blossom placed herself in front of her human, blocking the way. Every muscle of the dog’s body tensed, every sense directed toward the unknown with the concentration of a stalker careful not to disturb nearby prey. Prudence’s hand stroked Blossom’s head, and she felt rather than heard the answering swish of the feathery tail. Not too much longer.

When the candle flame danced before their eyes again, it was almost blindingly bright. Prudence could hear a whispery voice pleading with someone, though so faintly she could not make out the words.

There was no response. Just the lone murmur entreating a silent someone. Begging for some kind of acknowledgment?

With the singlemindedness of the expert tracker she was, Blossom moved directly toward the tiny blaze of yellow light. Not waiting for a command from Prudence, confident that her human would follow behind. She seemed to be communicating that neither of them was in any danger from the street child they’d tracked into the university’s cellars.

A rustle of paper reached their ears and the rich odor of ham, cloves, and honey rose above the grimy damp. Someone had unwrapped the package of sandwiches Prudence had been too preoccupied to eat.

A sixth sense warned the boy he’d been found.

As Blossom and Prudence emerged from behind a wide cement column halfway down the room, he leaped to his feet and stood facing them, elbows bent in front of a skinny chest, hands fisted like a prizefighter’s. Lit from below by a candle lantern, he cast fearsome shadows that danced above his head and climbed the wall behind him. But he was only an eleven- or twelve-year-old boy bravely confronting a menace he thought he’d safely eluded.

“We’re not going to hurt you,” Prudence said, her words echoing off the low ceiling, then losing themselves in the towering mass of moldering wooden desks, chairs, and bookcases. Crates of disintegrating leather-bound tomes.

An odor of unwashed human flesh and old blood underlay the smell of the sandwiches.

“Don’t be afraid.”

Eyes focused on the boy, determined not to react to the absurdity of his pugilistic stance, Prudence at first missed what had drawn Blossom’s attention. Until the dog whined as if in pain.

A girl lay curled up on a crude pallet made from tufts of horsehair stuffing pulled from ripped chair cushions, her face so covered in dirt and dried black blood that it was difficult to make out her features. Long blond hair spilled over her shoulders down to a small waist below which a filthy, ripped skirt had been carefully arranged over her bare legs for modesty’s sake. Like the boy, she was barefoot, her feet scarred with old wounds and scabbed with new injuries. Her fingers curled into the palms of her hands. Old and new purple and black bruises mottled the skin of her bare arms.

Blossom crouched beside her, yipping a high-pitched whine that sounded so like an attempt at speech that Prudence half expected the girl to open her eyes in response.

Nothing.

Neither the boy nor Prudence moved. Then, very gently, Blossom’s tongue flicked over the girl’s chin until a convulsive twitch of injured nerves jerked feebly through a tiny patch of white flesh.

Prudence dropped to her knees, two fingers of one hand searching the girl’s wrist for a pulse. She felt the boy try to push her away, then Blossom heave herself upright. A moment later she heard a familiar warning growl; a weight that had fallen against her back was relieved, and she understood that Blossom was holding the boy at bay, allowing Prudence to examine the girl without interference.

“Wake up,” she urged, letting go the wrist where a thready pulse skipped uncertainly. “Can you hear me? Wake up.” Prudence raised one of the girl’s eyelids, as she had seen his doctor do so often when Geoffrey lay unconscious, but she wasn’t sure what she was looking for other than an absence of blood. The girl’s skin was hot to the touch in places, cold and clammy in others, as though her body fought its way alternately through freezing chills and burning fever.

Prudence shrugged off the light spring shawl she was wearing, covering the inadequately clothed girl who was stubbornly holding on to life despite what must have been a terrible beating. Looking up, she saw the boy’s wide-eyed stare flit from her to Blossom, then back again. Frightened yet defiant. His fists had fallen to his sides, but they remained clenched, as though, given half a chance, he’d use them to pound his way back to the girl he’d been protecting. The unwrapped sandwiches lay at his feet atop the butcher paper.

“She’s badly hurt.” Prudence watched the boy’s face for signs of comprehension and agreement. “I can help, if you like.” She thought she caught a gleam of understanding in his dark brown eyes, but he neither nodded his head to acknowledge what she had said nor replied. She wondered if he spoke English, or if he was one of the flood of immigrants arriving daily in the city with nothing but willing hands and a desperate need to escape their homelands. She waited, then repeated what she had said in schoolgirl French, the only other language she could attempt to speak. “Elle est gravement blessée.” Still no sign that he understood.

Blossom whined again, and Prudence made up her mind. She didn’t dare leave the girl alone in the basement with only the boy for company, and she wasn’t sure he could be sent outside to ask for help. Blossom was her only resource.

“Go get Danny,” she instructed the dog. “Fetch Danny.”

For a brief moment Blossom seemed to hesitate. Then she nuzzled Prudence’s hand, barked warningly at the boy, glanced one final time at the girl who lay on the floor beneath her human’s shawl. A streak of red-gold flashed through the dimly lit basement, and she was gone.

“Now we wait,” Prudence said to the boy, settling back onto her heels, reaching for the sandwiches. She held one out to him until he took it, then wrapped the other in the butcher paper and laid it within reach of the girl’s hand to signal that no one would take it from her. “She’ll be hungry when she wakes up,” Prudence said conversationally, though privately she thought the injured jaw Blossom had been licking might be broken. The important thing was to keep talking until Danny Dennis arrived, keep talking so the sound of her voice would calm the boy and mesmerize him out of thoughts of flight.

“The dog’s name is Blossom,” she went on, holding the boy’s eyes with her own. “She lives in a stable with a large white horse called Mr. Washington who pulls a hansom cab driven by my friend Danny Dennis. Danny is an Irishman. You’ll like him. He’s big and bluff and sometimes rough in his speech, but he’s kind to animals and children. Blossom’s young master lived on the streets, as I imagine you do also. He was very ill, so Danny took him in and nursed him until he died of a consumptive pneumonia. Blossom stayed on and sometimes she spends a night or two in my stables, but she always goes back to Danny and Mr. Washington.”

Cradling her patient’s head in her lap, Prudence stroked the thin, bruised arms as she talked, lightly touching the girl’s forehead from time to time to check for fever. Sometimes the skin beneath her fingers seemed to burn; at other times it was as if the girl had died and her body begun to cool. She knew a victim of illness or physical abuse desperately needed liquids. On the doctor’s instruction, Prudence had spooned beef broth, tea, and watered whiskey into Geoffrey’s flaccid mouth for hours, every swallow a step toward recovery. But there was nothing she could give this sufferer. Prudence was one of the very few women in New York City who didn’t carry a tiny bottle of laudanum in her reticule.

“Why don’t you sit down here with me?” she asked the boy, smiling what she hoped was an unthreatening invitation to join the vigil at the girl’s side. “She’ll be able to see you better when she opens her eyes.” If she opens them. Prudence moved the candle lantern closer; there was only a finger’s width of stub left and no other source of light nearby. No light bulbs hung from the basement ceiling; the university’s governors hadn’t bothered to electrify the building’s basement.

She tried to judge how long the candle would last and hoped Blossom would find Danny parked at his usual stand near Trinity Church. She counted off the blocks between the end of Wall Street and Washington Square. Not far. Not far at all.

But the wait stretched on interminably.

When Danny came, it was with a rush of heavy footsteps and Blossom’s joyous barking to announce their arrival. Fresh spring air coursed through the stagnant basement; he’d left the door to the street flung wide, the one connecting the two basement rooms propped open.

“Now then, miss, what have we here?” Danny asked, his brogue deeper than usual at the sight of Miss Prudence MacKenzie crouched on a dirty cement floor with a badly injured young woman’s head on her lap and a belligerent street boy scrambling to his feet beside her. “Calm down, lad. Blossom, see he doesn’t try to do anything foolish.”

Danny bent over Prudence, lifting the shawl from the body stretched out beneath its dubious warmth. “She’s in a bad way, miss,” he said. “But I’ve seen worse.” He stretched the truth a bit because he read anguish on Prudence’s face. “Not to worry. We’ll soon have her where they’ll be able to fix her up.” Unless she died in his cab on the way to Bellevue. New York City’s streets were crowded, sometimes nearly impassable. It would take precious time to carry this girl to the city’s trauma hospital for the poor and indigent. Time she might not have.

“Not Bellevue, Danny,” Prudence said, guessing that was where he assumed she wanted them to go. “She needs to be tended by a woman doctor.” Prudence knew what damage an enraged sexual predator could inflict on a girl as y. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...