- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

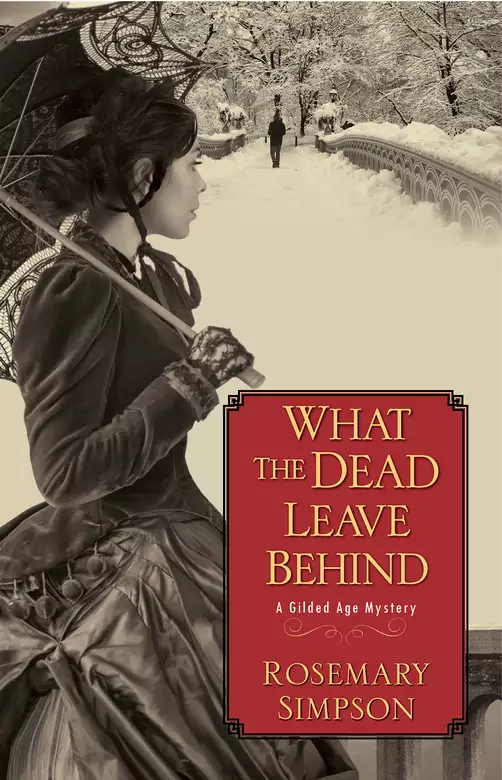

Synopsis

As the Great Blizzard of 1888 cripples the vast machinery that is New York City, heiress Prudence MacKenzie sits anxiously within her palatial Fifth Avenue home waiting for her fiancé's safe return. But the fearsome storm rages through the night. With daylight, more than two hundred people are found to have perished in the icy winds and treacherous snowdrifts. Among them is Prudence's fiancé—his body frozen, his head crushed by a heavy branch, his fingers clutching a single playing card, the ace of spades . . .

Close on the heels of her father's untimely demise, Prudence is convinced Charles's death was no accident. The ace of spades was a code he shared with his school friend, Geoffrey Hunter, a former Pinkerton agent and attorney from the South. Wary of sinister forces closing in on her, Prudence turns to Geoffrey as her only hope in solving a murder not all believe in—and to help protect her inheritance from a stepmother who seems more interested in the family fortune than Prudence's wellbeing . . .

Filled with richly colorful characters, fascinating historical details, and thrilling moments of suspense, What the Dead Leave Behind is an exquisitely crafted mystery for the ages.

Release date: April 25, 2017

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

What the Dead Leave Behind

Rosemary Simpson

The blizzard howled its way across Manhattan early Monday morning. Most of the city’s inhabitants stayed home; the wind was strong, the ice slippery, and the snow so blinding that familiar stoops and sidewalks were too treacherous to risk. People who out of curiosity opened their front doors had to struggle to close them again against the howling gusts. New Yorkers turned up their gas furnaces, checked basement coal bins, fretted over the size of backyard woodpiles.

Despite the dangers of the storm, there were those who worried that if they didn’t show up for work, there wouldn’t be any work to show up for. Times had been bad after the war; jobs were scarce, hard to find and keep. Too many husbands and fathers lived in fear of being fired; for every man earning a weekly wage, another was ready to step into his shoes. Daily help, mostly women, lived hand to mouth; to lose a day’s pay was to upset an already precarious balance. Empty bellies had to be filled no matter how treacherous the weather.

Easter was only three weeks away, they told themselves. How bad could a spring snowstorm get? How long could it last? Who’d ever heard of anyone freezing to death in mid-March? Few of the foolhardy who ventured out from their brownstones and apartments in the general direction of their places of employment got where they were attempting to go. Two hundred of those who did not turn back disappeared, not to be found again until the snow melted around their upthrust, desperate arms.

As Monday morning wore on, trains from the suburbs ground to a halt in monstrously tall drifts; the city’s horse-drawn delivery wagons and hansom cabs failed to appear on snow-blocked streets. In front of every apartment building supers and doormen shoveled as fast as they could, but the wind and the snow beat them back into lobbies and foyers where they stomped their feet, gulped hot coffee, and warned the building’s tenants against going out into the storm.

Already the phenomenon was earning itself nicknames. The Great Blizzard. The Storm of the Century. The Great White Hurricane.

Under any name, it brought death in its wake.

Wrapped in a fringed paisley shawl, Prudence MacKenzie stood at her bedroom window and tried to pick out where she had last seen the cobblestones of Fifth Avenue before the entire street disappeared under a blanket of white. All day long she had felt herself drawn to peer out through one or another of the mansion’s windows, searching for a figure struggling through the impenetrable white. Charles had said he would be bringing the final copies of their marriage settlement documents today, just as soon as Roscoe Conkling, her late father’s friend and lawyer, declared them fully in compliance with the Judge’s will.

No carriage could have made it through the icy, snow-clogged streets, but Charles was a man of his word and nearly as stubborn as the notoriously immovable Conkling. Prudence could envision both men arguing their way out of their warm, safe offices into a storm that neither would admit was stronger than either of them.

By late Monday afternoon she’d worried herself into exhaustion and fallen asleep fully clothed when she lay down on her bed to stretch out for a moment. She dreamed of Charles until another howling blast of wind hurled itself against the corner of the brownstone and woke her up.

In her dream Charles had been a figure barely discernible through fiercely waving veils of snow, a living sculpture of ice struggling blindly up Broadway from Wall Street, calling out to her.

The nightmare part of the dream had been that she couldn’t answer him.

New York’s fifty-eight-year-old ex-senator, Roscoe Conkling, was pleading a case that Monday morning. Flamboyant, indefatigable, and commanding enormous fees, he mushed his way two and a half miles down Broadway from his apartment in the Hoffman House Hotel to the United Bank Building at the corner of Broadway and Wall Street where he received one of the few telephone calls completed in Manhattan that day. Telephone, telegraph, and electric poles were already toppling down into the streets, blocking access, spitting and sparking until the cold, wet snow shorted out the lines. The judge before whom Conkling was to appear was snowbound at his home. Court had been canceled.

Resigning himself to being stuck in the office, Conkling waded through the paperwork that was so much a part of every lawyer’s life. This morning it was the last of the trust documents that his late friend, Judge Thomas MacKenzie, had had him draw up to safeguard the considerable fortune he had bequeathed to his beloved daughter by his first marriage.

Prudence, whose mother died when her only child was six years old, was two weeks away from becoming Mrs. Charles Linwood. Before that happened, Conkling had to be certain her interests were as well protected as the Judge had wanted. Not that Charles Linwood showed any trace of being the type of husband more enamored of his wife’s fortune than the person of the lady herself. Far from it.

The Judge had been delighted when Linwood asked for Prudence’s hand. Charles had gone from Harvard straight into his family’s law firm where he’d proved himself as adept at drawing up finely crafted wills and contracts as he was persuasive before a jury. Already a skilled lawyer with a bright future, Charles Linwood loved Prudence MacKenzie in the honest, gentlemanly fashion every father wished for his daughter. The man could be trusted to care for his young bride and make her happy in her new life.

It was a perfect match.

The afternoon was turning shadowy despite the whiteness of the mesmerizing snow. Prudence lit the gas lamps on her bedside tables, listening for a few moments to their reassuring hiss, drinking in the comforting light. She had been awake most of the previous night, ever since the storm began to blow in earnest. Regardless of the weather, she had seldom slept through the hours of darkness since her father’s death barely three months ago.

She had been given drops to dull the immediate agony of loss, but as the weeks of mourning wore on, a furious itching began to interrupt her sleep at night. She’d wake up to the bite of her fingernails scratching and digging at the thin, dry skin of her arms and legs. If she didn’t stop herself soon enough, rings of dried blood showed reddish brown beneath her nails in the morning. She’d open her eyes, light the gas lamps, then reach for whichever book she was currently reading. She would still be awake at dawn.

And always there was the aching longing for her father, the memory of standing at the gate of the family crypt, hearing the creak and clang of wrought iron shutting him in forever.

Prudence unbuttoned the left sleeve of her black mourning gown, pushed it above the elbow, and examined the skin, bending to hold the arm under the soft yellow glow of one of the lamps. The scratches that had so recently been an angry red had faded into the faintest of tracks, as if she’d absentmindedly run the tip of a folded ivory fan along the length of her arm. The itching was less, almost unnoticeable, tamed and soothed by the face cream she’d rubbed into the sore skin morning and evening. Something else, too.

The cup of boiled milk brought up to her from the kitchen every evening had sat undrunk on the mantel for hours again last night, an ugly, wrinkled skin formed across its surface. It was after she’d stopped drinking the nightly milk that she noticed the itching no longer tortured her, that when she woke in the night, it was with a clear head. Despite the fatigue of too little sleep, she now felt restless where for a while she had been so lethargic that it was all she could do to get through the day.

The first time she left the milk undrunk, her stepmother, Victoria, folded her lips in tightly, made an odd clicking sound deep in her throat, but said nothing except to remind her stepdaughter that it wasn’t the only thing Prudence had forgotten to do recently.

“You haven’t been yourself since the Judge’s funeral,” Victoria insisted. “I worry about you. Grief has been known to do strange things to a woman’s delicate sensibilities.”

It wasn’t grief that was destroying Prudence, deep though that was. It was the laudanum she had been given to help her through the mourning and soften the pain of loss. Prudence recognized its effects, but not its dangers. Not until it was almost too late.

When her mother’s pain had grown too excruciating to be borne, the only thing that eased it was the tincture of opium commonly sold as laudanum. She’d seen Sarah MacKenzie claw fretfully at the thin skin of her chest, drops of blood staining her nightgown. Not everyone who took laudanum suffered from itching, but those who did often scratched themselves raw.

One day Prudence had touched a finger to the spoon lying on her mother’s bedside table and then licked the bitter drop from her skin. Her father knew what she had done the moment he saw the grimace on her face and the telltale brown smear on her fingertip.

“Promise me you’ll never taste Mama’s medicine again, Prudence. It’s only for very sick people, and my precious little girl isn’t sick, is she?”

She had promised.

Then years later the father she adored died and she found herself alone with a stepmother she despised and distrusted and an uncle by marriage who made her skin crawl every time he looked at her. Her world fell apart, and so did Prudence. Laudanum was prescribed. Nearly three months of what were supposed to be only a few drops a day had brought her perilously close to the cliff of ladylike addiction. She remembered the worried frown on Dr. Worthington’s face when he took the brown glass bottle with its tight-fitting cork out of his leather satchel.

“Not too much,” he cautioned. “I would limit the dosage to five drops at a time, and no more frequently than once or twice a day.”

Stepmother Victoria had taken the bottle from the doctor’s hand with ill-concealed relish.

“She’s not to dose herself, Mrs. MacKenzie.”

“Of course not, Doctor.”

“Accidents have been known to happen.”

Barely ten years older than her stepdaughter, Victoria was now a widow whose much older husband died less than two years after pronouncing the marriage vows. By the terms of the Judge’s will, this relative stranger had immediately upon his death become the trustee of her nineteen-year-old stepdaughter’s inheritance and the arbiter of her every daily activity. But the legal loophole of Prudence’s fast-approaching wedding would force Victoria to relinquish the control she obviously enjoyed. The mask behind which lay another Victoria was slipping; power once seized is never given up without a fight.

Prudence was counting the days until she would pass from the guardianship of a stepmother to the protection of a husband, slipped along with the signatures on her marriage contract, her future safely, predictably, and comfortably arranged by the father who was no longer here to care for her himself. The Judge had built high legal fences around his only child so no one could take away what was rightfully hers, had foreseen all eventualities. Or had he?

Two weeks after Dr. Worthington gave the first bottle of laudanum to Victoria MacKenzie, Prudence’s stepmother declared Prudence capable of measuring out her own doses. After all, she wasn’t a child any longer. Victoria handed over the brown bottle with a smile of encouragement, a pat on the hand, and a promise that when that bottle was empty another would be obtained.

Prudence hardly noticed that the doses she gave herself gradually grew larger. Five drops, then six, then seven. Laudanum numbed the agony of losing a parent, flattened out emotional peaks and valleys, made it possible to sleep. And really, it was only drops.

Charles worried, she knew he did, though he said nothing.

Not until the bedtime milk began appearing did she begin to wonder how much laudanum she was actually ingesting every day, how much was being given to her in addition to what she prepared for herself. And why? The wedding was so close. Victoria would be leaving the house that would then become Charles and Prudence’s first home together. The Judge had bought his second wife an apartment in the Dakota before he died. As always, he’d seen to everything.

Or had he? Prudence was convinced that Victoria MacKenzie never did anything that would not benefit her, never moved a muscle unless it was to her advantage. She wondered if all stepdaughters disliked their father’s new wives, if perhaps she should be less wary of Victoria. The Judge had taught his daughter to be fair, to consider an argument from every side. But where Victoria was concerned, there were questions, always questions. Never answers.

Now that the laudanum fog had dissipated, Prudence’s unease about her stepmother was fast becoming something stronger than disquiet or simple anxiety. It was suspicion tinged with apprehension, a feeling that Victoria was determined to shape Prudence’s future in a way the Judge would never have countenanced. Was there some hidden menace in the wording of her father’s will that not even Charles had spied out? No matter how hard Prudence tried to figure out her stepmother’s intentions, Victoria was always one step ahead. What could Victoria possibly gain if Prudence became one of those sad women whose pathetic lives were lived inside a brown glass bottle?

It was only when she tried to deny herself that Prudence discovered how very deep, dark, and comforting was the well down which she had begun to slide. No one had forced her to seek solace in laudanum. A trusted family doctor had provided a time-proven remedy, but cautiously, and she had taken it willingly. Drop by drop, until finally she knew it was time to stop. Some women carried tiny vials of the bitter potion with them everywhere they went and appeared none the worse for it. She did not think she could be one of them; the urge to feel the powerful warmth spreading through her body was too strong, too compelling.

She could not bear it if Charles broke his discreet silence, if he were finally driven to ask about the laudanum. And worst of all, what would her father say if he knew?

Since the night she had first denied herself the laudanum-laced milk, Prudence had resolutely refused what her body craved. She made sure Victoria saw her mix five drops of dark brown liquid into her coffee at the breakfast table and six drops into her afternoon tea, but she knew herself to be finally free of the drug. She replaced the laudanum in the bottles Victoria gave her with strong unsweetened tea nearly as bitter as the tincture of opium. It wasn’t difficult to feign a moue of dislike as she drank it down. Victoria always smiled when Prudence shuddered at the sharp afterbite. To do any good, medicine had to taste bad. Everyone knew that.

The question she could not answer was why it was so important to continue to pretend she was taking Dr. Worthington’s laudanum, why she emptied her nightly cup of milk out the window, why she didn’t say a word to anyone about what she suspected her stepmother had tried to do to her.

Two more weeks. Then she’d be with Charles as his wife. Safe.

Last night, sometime between midnight and dawn, while the storm was gathering strength, Prudence had carried the teacup of tepid milk with its calming dose of laudanum to the window against whose glass panes snow had already mounded. She had eased the window frame open, gasped delightedly at the touch of icy flakes on her fingertips, then watched the milk freeze as it flew through the wind, as it became one with the snow and fell harmlessly into the street below. Every refusal was a victory.

She was not naturally a secretive person, nor one given to fanciful delusions. Her father had trained her to see life as realistically as intelligence and a tender heart could bear.

But there was something about Victoria that was deeply disturbing, even frightening.

Two more weeks. Then she’d be safe.

With his desktop clear for a change, Conkling ate the last two apples in the bowl of fruit that was normally replenished every morning by the very competent secretary he’d occasionally caught in the act of eating chocolates at his desk. Sure enough, there was a half-full box of cherry cordials in one of Josiah’s drawers. Roscoe scribbled an IOU, dropped it into the now-empty container of candy, and gave himself a mental reminder to replace what he’d eaten.

Conkling was an anomaly among his peers. Far more athletic than most men in their late fifties, he rarely drank alcohol to excess and did not smoke. He sported a full, bushy beard and decked himself out in bright waistcoats and cravats that never allowed his six-foot-three-inch frame to blend into a crowd. People who disliked him called him a peacock and names so foully descriptive they were unprintable.

Roscoe’s chief vice was women, the lovely creatures. Every one of New York’s seven newspapers had scrupulously dissected his long and scandalous liaison with Kate Chase. Her father had been Lincoln’s Secretary of the Treasury, then Chief Justice of the Supreme Court; she had married the governor of Rhode Island. Politics and illicit love always made good copy.

As much as Roscoe enjoyed reading about himself, it was the possibility of a dangerous or even fatal encounter with a husband that added that certain je ne sais quoi to every affair. He thrived on risk; every new adventure made the blood run faster through his veins. The taste of the chocolate cherry cordials on his tongue the day of the blizzard was nearly as sensuous as the first encounter with a new woman.

It was getting darker. Still midafternoon, but definitely darker. And there seemed to be something wrong with the gas lamps that usually lit up Broadway like a string of yellow pearls. The wind blew steadily between the buildings, and the snow never stopped falling. He’d thought to wait out the storm, confident it couldn’t continue so violently for more than a few hours, but there hadn’t been any letup. He’d sent the MacKenzie trust papers down to the Linwood office on the floor below hours ago. It wouldn’t surprise him if young Charles had already taken them to Prudence. Maybe it was time to think about leaving. While he still could.

“Mr. Conkling. I thought I saw your light on. Almost everyone who managed to make it in today has already left.” Charles Linwood stood in the doorway, bundled against the weather in thick coat, muffler, and tall top hat. One hand held a pair of gloves, the other a heavy briefcase. “My father talked me out of trying to take the MacKenzie trust papers to Prudence until tomorrow when all of this will have blown through. I’m sure he was right, though I wish I’d been able to get a message to her. It’s too late now. The snow doesn’t seem to be lessening, so I’m leaving. What about you?”

“I’ll keep you company if you’re going toward Union Square.”

“I am, and I’m hoping to find a hansom cab somewhere along Broadway.”

“I haven’t seen any kind of vehicle in the last few hours. Not a cab or a carriage in sight.”

“It wasn’t too bad early this morning. I’m sure some of the sidewalks have been shoveled by now.”

“The snow’s still coming down too heavily to be able to see very much.” Conkling turned from the window.

“If the drifts are too high, we can always stop at one of the hotels along the way.”

“I hope Prudence didn’t try to go out today.”

“She’s much too sensible for that.” Charles Linwood smiled as he said it. He was immensely fond of Prudence MacKenzie, and looking forward to their marriage. They’d always gotten along so well as friends that it was inconceivable they wouldn’t grow even closer as husband and wife.

Conkling reached for his coat. “Losing her father was a terrible blow. The Judge was a good friend; he sent Jay Gould along to me, and Mr. Edison. They were among my first clients when I came back to the city. I miss Thomas MacKenzie like a brother.”

“He and my father practiced summation speeches on one another when they were just starting out. My deepest regret is that I won’t have the honor of knowing the Judge as a father-in-law, but I’m sure Prudence and I will want to welcome you often as a guest in our home.”

“And I’ll be more than happy to come. Has Mrs. MacKenzie begun to move her things out yet?”

“She says she plans to be gone by the time we get back from Saratoga Springs.”

“Not France or Italy?”

“Perhaps next year. Prudence is still very fragile. I asked where she would most like to spend our honeymoon, and she chose Saratoga. The Judge took her to the Grand Union Hotel every summer for years.”

“And so that’s where you’ll also be staying?”

“I don’t think she’d be content anywhere else.”

“I wish you both great happiness, Charles.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“When you get back, when you have time, we should sit down together. The Judge was meticulous in seeing to his affairs, but there are sealed envelopes he gave me that are not to be opened until after the marriage has taken place.”

“I didn’t know that.”

“No reason why you should. I haven’t said anything to Prudence, either. My instructions were to see to them within the first month after the wedding. The Judge smiled when he handed them to me, so I don’t suppose there’s anything much to be concerned about. It may just be his way of ensuring that you both receive whatever fatherly advice he wanted to give you.”

“The will was a bit unusual.” Charles Linwood hesitated. Until he became Prudence’s husband, he was too much the gentleman to feel entirely comfortable discussing the fortune bequeathed to her by her father.

“In the normal way of things, it might have been expected that the family home would go to the widow, at least for the remainder of her lifetime,” Conkling agreed. “But Mrs. MacKenzie has only lived there for the two years of her marriage to the Judge. She doesn’t have the ties to it that Prudence does. Thomas was the soul of discretion. It was no secret to him that his daughter didn’t have the same warm feelings for Victoria that he did. He provided very well for his widow, just not perhaps exactly in the way she might have been expecting.”

And that, Roscoe Conkling’s headshake seemed to say, was his last word on the subject. For the moment, at least. Until after Saratoga. After the wedding. After this damned blizzard that looked like it was capable of blowing them over as soon as they stepped out of the building.

People likened these streets to canyons; they funneled wind and rain and now snow down narrow walled passages that increased velocity and turned harmless raindrops and snowflakes into missiles that stung the skin and made the eyes water.

“Are you ready?” Conkling asked.

“As I’ll ever be,” laughed Charles.

Even before they managed to make it onto the sidewalk, both men realized it was going to be worse than either of them had imagined.

As Conkling and Linwood pushed open the doors of the United Bank Building, the force of the wind threw them back into the vestibule. Conkling thought he would have been slammed against the marble floor if Linwood had not grabbed his arm and held on to him as the two men struggled to regain their footing. Snow swirled into the lobby, making the expensive Italian marble as slippery and dangerous as the icy street outside.

“I’m not sure we’re going to make it up Broadway after all,” Linwood said, one gloved hand holding on to the handle of the door that had almost flattened him. “We might be better off spending the night here, Mr. Conkling.”

From behind them came a shout, then the sound of rapidly approaching footsteps. “I thought I heard voices. I stopped by your office because I knew you’d come in today, Mr. Conkling, but you’d already left.” William Sulzer, whose office was down the hall from Conkling’s, had been in such a hurry that he’d left his coat unbuttoned and carried his wool scarf in his hand. “I hoped I’d catch up with you.”

“It’s very bad out there, William.” Charles took a few cautious steps across the slick wet marble floor.

“Nonsense,” scoffed Conkling. “We may have some difficulty making our way along the sidewalk, but once we get around the corner we’ll find a hansom cab. We’re going toward Union Square, William.”

“Perfect. I’ll join you, if I may.”

It was on the tip of Linwood’s tongue to tell both of his fellow lawyers they were as mad as the Hatter in the Alice story Prudence loved to quote to him. She’d told him more than once there was a model for every one of Mr. Carroll’s odd characters in their own immediate social circle. He certainly felt as though the blizzard raging outside had frozen them in Alice’s upside-down world. No place to go and no way to get there.

Conkling and Sulzer peered out the doors, bickering amiably about whether they should walk to the corner of Wall Street and Broadway in search of a hansom, or strike out through the drifts in the direction of Union Square and keep going until a cab came along. New York City was famous for its sturdy horses; you saw them all the time in winter, nostrils steaming clouds of vapor as they slogged along under the protection of heavy canvas or plaid wool blankets. The snow might be too thick at the moment to be able to make them out, but there would definitely be horse-drawn hansoms out there somewhere.

“Charles, are you with us?”

“William, I’m not sure we should attempt this. It’s getting darker and colder by the minute.”

Roscoe Conkling flashed a challenging smile at the much younger men. “Two miles to Union Square, gentlemen. Forty-five minutes more or less. An easy late-afternoon stroll.” He could already imagine captivating an audience with the tale of how he’d conquered the elements when lesser men had surrendered. He pushed open the heavy outer door and disappeared through a curtain of white.

“We can’t lose sight of him.” William Sulzer slammed his way out into the snow. “Mr. Conkling, we’re coming. Stand still until we get to you,” he shouted.

If he caught a catarrh from the wind whipping around his head, Charles knew that Prudence would have words to say about being careless with his health this close to the wedding. But if he didn’t follow Conkling and Sulzer into the storm, he’d never live it down. The story would be told and laughed over in every law office in the city. On the whole, he’d rather take his chances with Prudence. “I’m coming,” he yelled over the wind that bellowed as loudly as one of the new steam-engined trains rushing through the city.

The three men trudged off together toward Trinity Church, though they could barely make out its impressive gothic revival bulk. The tall cross-topped spire that usually dominated the skyline had disappeared. They saw nothing but blinding whiteness, heard nothing but the howl of the blizzard roaring down the city’s canyons. By the time they reached their first destination, where Wall Street met Broadway, they knew there would be no long line of hansom cabs lined up waiting for passengers, patient horses munching contentedly in their nosebags.

Snowdrifts had piled up against the massive arched doors of Trinity Church; in places the wind scoured the sidewalk almost clean, only to dump impenetrable snow mountains higher than the top of a tall man’s head farther on. Broadway stretched before them in glorious emptiness. Landmarks were unrecognizable; utility poles had toppled into and across the street like a bizarre forest of branchless young pines in a tangle of snapping, buzzing wires.

Roscoe Conkling led the way, his tall, athletic body moving like an upright white polar bear along the ice floes of Broadway. His luxuriant beard froze stiff on his chest; icicles glittered, melted under his breath, dripped, and reformed almost immediately. Snowflakes hung from his eyebrows, piled up on his eyelashes, clung to his hat and the fabric of his coat. He should have been as frozen as the landscape around him, but he wasn’t; the energy it took to keep moving generated a heat that defied nature. Charles Linwood and William Sulzer, struggling along behind and occasionally beside him, told themselves it was their duty to see the older man to warmth and safety, to continue on as long as he did. They had to match Conkling step for step.

They almost didn’t believe their eyes when a hansom cab pulled up beside them, the horse stomping its great hooves as billows of steam surged from its nostrils. The driver had swaddled himself hat to boots in blankets so all they saw of his face was a pair of dark eyes peering down at them.

“How much to the New York Club at Madison Square?” shouted Conkling.

The driver of the hansom cab looked at the three swells as if calculating the price of their fur-collared coats and beaver hats, gazed for a few moments at the empty stretch of Broadway that lay ahead, turned to peer behind through the snow as if searching for another vehicle. “Fifty bucks,” he growled. “Take it or leave it.”

Sulzer was already reaching for the carriage door when Conkling raised his

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...