- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

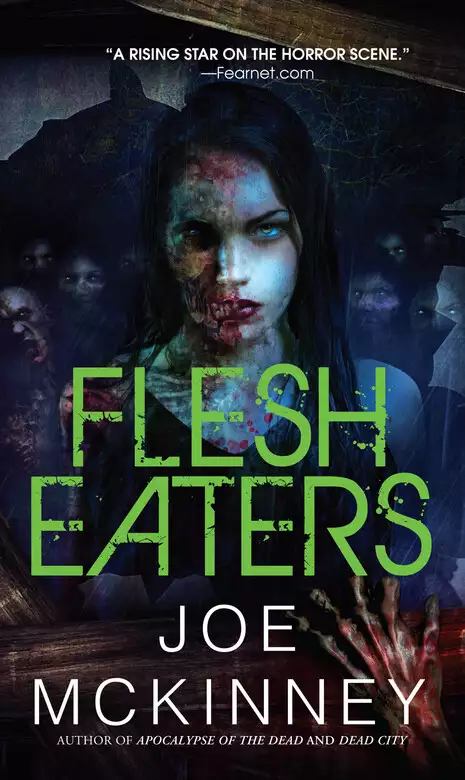

Synopsis

They rise...

Out of the flooded streets of Houston, they emerge from plague-ridden waters. Dead. Rotting. Hungry. And as human survivors scramble to their rooftops for safety, the zombie hordes circle like sharks. The ultimate killing machines.

They feed...

Houston is quarantined to halt the spread of the zombie plague. Anyone trying to escape is shot on sight-living and dead. Emergency Ops sergeant Eleanor Norton has her work cut out for her. Salvaging boats and gathering explosives, Eleanor and her team struggle to maintain order. But when civilization finally breaks down, the feeding frenzy begins.

They multiply...

Biting, gnawing, feasting-but always craving more-the flesh-eaters increase their ranks every hour. With doomsday looming, Eleanor must focus on the people she loves-her husband and daughter-and a band of other survivors adrift in zombie-infested waters. If she can't bring them into the quarantine zone, they're all dead meat.

Release date: April 1, 2011

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Flesh Eaters

Joe McKinney

Eleanor Norton’s earliest memories were of hurricanes. As a little girl, she had seen Rita and Ike and Jacob rip Houston apart, their winds shearing off her neighbors’ rooftops and sending them sailing away like kites. She remembered her family huddling like frightened animals in the hall closet, her mother trying to be brave but still squeezing her so tightly she’d left bruises on Eleanor’s skin. Then, in high school, she’d lived through Brendan and Louis, storms that carried shrimp boats ten miles inland and blanketed the city with ocean water that dappled like molten copper in the morning sun. She still carried memories of water moccasins gliding past the top of the swing set in her backyard and pickup trucks floating like rafts down her street and grown men on their rooftops, crying without shame for all that they had lost.

She never outgrew that fear of storms. Even now at thirty-five, a mother of a beautiful twelve-year-old girl, a wife to a wonderful man, a looming hurricane could still reduce her to jelly. The wind and the slashing rain and the overwhelming floodwaters touched some deep atavistic impulse inside her to run for shelter. Cataclysmic storms were a fear many Houstonians lived with, though most never talked about it. But now, as she stood in line at the Wal-Mart, she could sense her own terror mirrored in the scurrying anxiousness of nearly everyone around her. Like her, they just wanted to buy their water and batteries and cans of Sterno and get home to their families before the storm made landfall. Waiting in line like this was maddening.

Eleanor had been doing fine in the days leading up to Hurricane Hector. She was working in the Houston Police Department’s Emergency Operations Command, attending all the briefings, and bringing home what she learned to her family, making sure they were ready. The ritual of getting prepared had helped to keep the fear at bay. But that morning, when she left for work, the sky had been a bloody red, and all the terror she’d felt as a child came back in a flood. She’d gone to work—and tried to work, she really did—but she was distracted and irritable. Captain Mark Shaw, her boss, had noticed. He noticed everything; and, in truth, it hadn’t been hard to tell what was going on with her. She kept returning to the main window, the one that looked out over the green lawns of the University of Houston. Outside the sky was changing from a horror-movie red to a windy, sodden gray, and she couldn’t take her eyes off it.

Captain Shaw, who, despite his reputation, was not without mercy, sent her home.

“You’ll do more good with your family anyway,” he told her. “We got this. Go on home.”

“Really? You’re okay with me leaving?” she asked.

“It’s no big deal. Everything that can be done has already been done. Nothing else to do here but ride it out. You can do that at home just as easily.”

“I really appreciate this, Captain.”

He dismissed her with a wave of his hand.

“I’ll see you in the morning,” he said. “Worse comes to worst, and we get some bad flooding, I’ll send a boat by for you.”

And so she’d gone to Wal-Mart for a few last-minute things, her fear mounting as the wind picked up and the sky grew darker. When she finally made it through the checkout line and walked outside to the parking lot, the gray sky above her was limned with an eerie chemical green. The air was dense as a wet towel against her skin. She swallowed nervously, ducked her head against a gusting breeze, and rushed to her car.

She hardly remembered the drive home.

But once she was home, she and Jim and their daughter Madison still had so much to do to get ready. She could hear Jim with his power drill out on the front porch putting up plywood over the glass, and, looking out the little window above the kitchen sink, she mouthed a silent plea for him to hurry.

It was getting really scary out there.

Part of Bays Bayou ran through the greenbelt behind their house, and Hector’s storm surge had caused its waters to rise significantly. Already there was an inch or so of brackish water covering their lawn, and a sharp, howling wind sent lines of lacy silver waves through it.

They were surrounded by cottonwood and pines and giant oaks, and the same wind was tossing their branches back and forth, filling the air with leaves. Earlier that afternoon Hurricane Hector had been upgraded from a Category Three to a Category Five storm, meaning that it would blow inland with winds over one hundred fifty-five miles per hour; and though she tried to suppress the thought, she kept having visions of a sustained blast of wind breaking off tree limbs and shooting them like arrows through the sides of their home. It had happened before, during Rita and Ike, when she was a little girl.

She shook the memories of those storms from her mind and focused her attention out the window. From where she stood she could just see a corner of Ms. Hester’s house across the street. The woman was eighty-four and struggling with what Eleanor suspected was incipient Alzheimer’s disease; but she was a sweet old lady and, with both Jim and Eleanor’s parents dead, had even filled in as the grandmother that Madison had never known. There had been several years, right around the time Madison was starting school and Eleanor was still slaving away as a detective in the Houston Police Department’s Sex Crimes Unit and Jim was working at Gulfport Petrochemical, when they hadn’t been able to afford child care. They were working all the time, but still miserably broke. Ms. Hester had come to their rescue. She took care of Madison during those years—cooked her dinners, taught her to paint, even picked her up from school on early-release days—and in so doing had earned a special place in Eleanor’s heart. In all their hearts, actually.

And so it was with considerably more than neighborly concern that Eleanor watched the wind thrashing the pecan trees that surrounded Ms. Hester’s little one-story white house. Madison had spent the last six summers collecting pecans from those trees, she and Ms. Hester shelling them and turning them into pecan pies and candied pralines. The trees were beautiful, even useful in their way, but they were notoriously ill-suited for bad weather. The wood was soft enough that the weight of the nuts alone could cause limbs to snap off in late summer. A strong Category Five hurricane wind would blast the trees to bits. How long would it take, she wondered, before one of those bits lanced through the roof, or a side wall, sending shards of glass through the house like bird shot from a twelve gauge?

“Mom, you okay?”

Eleanor half turned from the sink but said nothing.

“Uh, Mom, hello?”

This time Eleanor turned around. The thick note of sarcasm in Madison’s voice was something new, something she’d picked up, Eleanor suspected, from Susie Tyler and Brandy Moore, two girls who had just recently become Madison’s closest friends. The three girls spent nearly every day that summer running around together, sleeping over at each other’s houses, learning how to be teenagers together. It was natural behavior, Eleanor knew, but that didn’t mean she had to like it. Susie especially seemed like a bad influence, always so loud and disrespectful to the other girls’ parents. She had an annoying habit of making everything a competition between her and Madison, never missing a chance to gloat over some small victory or rub in some awkward moment on Madison’s part. And at twelve, Madison was having plenty of those.

Still, Eleanor backed off from actually telling Madison she couldn’t hang out with Susie. Her own mother had been a shrew when it came to Eleanor’s friends and had taken an almost sadistic delight in pointing out how much she disliked the girls Eleanor ran around with. It had made her afraid to have friends over, and Eleanor promised herself she wouldn’t be the same way, even if it meant swallowing the urge to fire a broadside here and there.

“I think it’s full, Mom,” Madison said, nodding at the sink.

Eleanor glanced behind her and saw that the five-gallon plastic water jug she’d been filling at the sink was indeed running over. She turned off the tap, poured off a little, and then screwed down the cap.

She lifted it from the sink with a grunt and put it on the floor next to the other four jugs she’d just filled.

“That’s the last of them anyway,” she said.

Madison was sitting cross-legged on the linoleum floor, putting cans of soup into a cardboard box, but she paused long enough to study her mother.

“Mom, are you okay?”

“I’m fine, honey.”

“You sure? You kinda zoned out there for a second.”

Eleanor smiled, but didn’t respond. There were times, certain moments when Madison had her head turned just the right way, when Eleanor could see how much her daughter really looked like Jim. It was in the profile, mainly. They had the same little upturn at the point of their nose, the same tapered chin, the same little tiny ears. Madison was the adolescent girl version of her father; but whereas those same features gave Jim an intelligent, studious aspect—especially when he wore his glasses—in Madison they became stunningly beautiful.

That girl is going to break a million hearts one day, Eleanor thought, and it was an idea that both terrified and delighted her.

“Why don’t you take those upstairs, okay?” Eleanor said, nodding at the box of soup.

“I can’t lift it.”

“What? Sure you can.”

“No, Mom,” she said, the sarcasm oozing back into her voice, “I can’t. It weighs, like, a whole ton.”

“No, it doesn’t. And don’t say ‘like.’ You know I hate the way that sounds.”

Madison sighed and made a dramatic show of rolling her eyes.

“Fine,” Eleanor said. “We’ll get your dad to do it. In the meantime, find something else you can carry. What’s next on the family list?”

Madison huffed indignantly, then picked up a yellow, coil-bound notebook that Eleanor had prepared to guide the family during a hurricane. She called it their family disaster plan. It contained nearly everything they would need to know about the contents of their supply kits and evacuation routes, plus contingency plans for getting the family back together again after the storm, should they get separated. Each member of the family also had a backpack that contained an individual ninety-six-hour supply kit, a personal version of the yellow disaster plan notebook, family photos, important numbers, and a couple hundred dollars in cash. The backpacks were already upstairs. What Eleanor and Madison were doing now was checking off the family supply kit for sheltering in place and carting the contents upstairs, just in case the floodwaters swamped the first floor of their house.

Madison read from the list, pointing to items as she said their names. “Next up is sanitation. Toilet paper, soap, lady-time stuff”—Madison’s eyebrows raised slightly at her mother’s euphemism for feminine hygiene products—“disinfectant, bleach, garbage bags and ties. Why do you have those on here twice?”

“What?”

“Garbage bags and ties. You’ve got them here and in the Miscellaneous section.”

“The sanitation section ones are for when you have to go to the bathroom. There should be a bucket with a tight-fitting lid there, too.”

Madison’s lips parted slightly, her nose crinkling in disgust. “A bucket? Mom, that’s gross.”

“No, that’s survival, kiddo. You’ve never been through one of these storms. You don’t know how bad it can get. I remember when I was a girl the water was off for two weeks after Hurricane Ike. What do you think happens when the toilets stop flushing?”

“Well, yeah, but . . .” Madison trailed off, her gaze shifting to the box of plastic trash bags as if she was suddenly too grossed out to touch them.

“You’ll live,” Eleanor said. “If it’s all there, just take it upstairs.”

The smile disappeared from Eleanor’s face as she watched her daughter cart yet another cardboard box of supplies upstairs. There were rough times ahead, and the girl was in for one hell of an education on the fury of nature.

The thought sent Eleanor even deeper into her own head. She had talked with Jim an awful lot lately about how fast Madison was growing up. Her thirteenth birthday was only two months away, but the changes had already started. She and Madison had had the talk about the lady time, and it had been a lot harder, a lot more embarrassing, than Eleanor had expected it to be. But in a way that talk had prepared her to think of her daughter as a woman, something that Jim was having a much harder time doing. Perhaps it was Madison’s smile, that giggly little smile of hers that so perfectly recalled the way she looked as a toddler. Or perhaps it was just Jim’s stubborn streak. Eleanor wasn’t sure. But whatever the reason, he seemed determined to avoid the issue. He still called Madison his little girl, and in fact had started using the phrase more and more in recent months, which indicated to Eleanor that he knew the truth, at least on some level, but was unwilling to face it.

She couldn’t blame him. Not really. There were times—plenty of times, in fact—that she didn’t want to face it, either.

Jim’s electric drill had gone silent as he moved to a new window. The wind, too, quieted for a moment. And in that lull, Eleanor heard the sound of arguing from across the street. She craned her head out the window, and what she saw there made her chest tighten with both pity and rage.

Ms. Hester was standing in the front yard, looking smaller and even frailer than she had earlier that day, when Eleanor had passed her on her way into work. The wind was billowing her housedress out to one side, and her arms were crossed over her chest in a gesture that made her look completely helpless. Rain rings formed chain-mail patterns in the water at her feet. Standing at the edge of her lawn, next to a beat-to-hell red pickup, was her grandson, Bobby.

When the guys at work mentioned meth heads, Bobby Hester was the image that flared up in Eleanor’s mind. He was tall and lanky, so skinny his clothes fit him like a potato sack on a flagpole. He wore his filthy blond hair down to his shoulders, and there were tattoos all up and down his arms, where the veins stood out like electrical cords beneath his skin.

He was the one Eleanor had heard yelling, and as she watched he opened the passenger door of his truck and put Ms. Hester’s TV inside.

That manipulative, thieving little bastard, she thought.

Though she couldn’t hear what Ms. Hester was saying, she could figure it out without any real difficulty. Ms. Hester was scared. She wanted him to stay with her during the storm. She was probably begging him to stay.

But Bobby Hester would never agree to something like that.

He had miraculously reappeared in her life about two years ago, at the same time she started slipping a little from the Alzheimer’s. To Eleanor it was no coincidence. He was a wolf sensing an easy meal, nothing more. Certainly not the long-lost grandson he no doubt claimed to be. Eleanor had tried to say as much, but Ms. Hester wouldn’t listen to a word of it. She adamantly refused to see Bobby as bad news. She welcomed him into her home. And he repaid her kindness by robbing her blind.

Now he was telling her to stop her whining. That he’d be back. That he just wanted to take her electronic stuff someplace safe. She wasn’t holding back, was she? There wasn’t a TV someplace she hadn’t told him about?

The fucking bastard is gonna pawn everything she owns so he can get cash for his meth, Eleanor thought, and suddenly the image of her putting a bullet in his brain was very strong, and more than a little satisfying.

A knock on the window made her jump. It was Jim, looking in on her, his knuckles still poised at the glass.

She undid the latch and opened the window.

“You’re seeing this, right?” he said.

“Yeah.” Her pistol was upstairs in her backpack, and she couldn’t help but wonder if she’d be able to hit Bobby from here. One good head shot would be all it’d take. “That man’s a slime ball.”

“That’s true,” Jim said. “You want me to go over there and tell her to stay with us?”

“I tried that this morning. She kept saying Bobby was going to stay with her tonight. That’s all she would say. ‘Bobby’s coming. I’ll be okay, Bobby’s comin’ over.’ ”

“Yeah, well, I don’t think that’s gonna happen.”

“Don’t you think I know that?” she snapped, and then instantly wanted to pull the words back. “Sorry.”

He nodded. “It makes me angry, too.”

“Yeah.”

He had a hand on the windowsill. He was filthy from putting up the plywood screens and cleaning up the stuff from the yard that might blow around during the storm and cause damage, but she didn’t care. It was good to be home with him. She put her own hand on top of his and squeezed.

He looked past her to the kitchen. “Where’s Maddie?”

“Upstairs. We’re gonna need you to carry the food boxes.”

“Sure.”

In the distance, lightning flashed across the sky. A roll of thunder followed along close on its heels. The air smelled ominous, heavy with the scent of salt and sea.

“You can smell it, can’t you?” he said. “The storm’s getting close.”

“Yeah.”

Across the street, Bobby’s pickup fired up with a loud snarl, and he sped off, leaving Ms. Hester standing in her front yard. Ms. Hester watched him go, obviously frightened, then slowly turned and went back inside her house.

“What do you want to do about that?” Jim asked.

“She’s family. We’ll take her in. As soon as we’re done loading all this stuff upstairs I’ll go over there and get her.”

“And if she won’t come? You can’t make her leave if she doesn’t want to.”

“She’s family, Jim. I won’t let her ride this thing out alone.”

“Okay,” he said, and with that they closed the window and Jim dropped the last sheet of plywood into place over top of it.

The first heavy band of rain came about thirty minutes later. It slammed into the side of the Nortons’ house in enormous wind-driven blasts, beating against the roof and the exterior walls, roaring like a passing freight train. It lasted less than two minutes, and then slackened off to a steady, needling patter.

They were in the game room upstairs. Madison’s room was next door, but they had tacitly decided that the whole family would sleep here. Now father and daughter were rolling out sleeping bags, the two of them laughing over some stupid thing Jim had said. They seemed to be having a pretty good time of it, Eleanor noticed. She hadn’t heard Madison laughing like this in a long while. Not even the wind and the rain outside seemed to bother her, at least not yet. She had her daddy with her, the two of them too absorbed in being goofy to be afraid of a little wind and rain. Jim was treating this like a big adventure, at least in front of Madison, and Eleanor was glad for that. It would help Madison to remain calm when things got really bad here in another few hours, and perhaps it would also help Jim to hold on to his little girl for a little while longer. A crisis like this, it would be terrible for the great wide world outside their house; but here, inside, the Norton family was in a good place.

Eleanor and Jim had met fourteen years before, back when she was a brand-new patrolwoman working every extra job she could find just to make the rent on a rattrap apartment on Houston’s lower east side.

She was working security at a Flogging Molly concert the night he came into her life. He was with a group of his friends from his college days. He was cute, she thought. A little nerdy, maybe—certainly more of a nerd than the cops she was used to hanging out with—but cute. He kept coming up to her, using really weak excuses to strike up a conversation; and as much as her cop training told her to disengage so she could watch the crowd as she was being paid to do, there was a very human part of her that liked the attention.

During a break between songs he worked up the nerve to ask for her number.

“No way,” she said. “Not while I’m working.”

“Not while you’re working? What does that mean?”

“It means I don’t give out my number to strange men while I’m working.”

“I’m not strange.”

“You know what I mean,” she said, smiling despite herself.

“You can trust me,” he said. “I’m a good guy. Come on, I don’t bite.”

Her gaze shifted from the crowd back to him. He was leaning against a wall next to a dartboard, trying to look cool, but only managing a barely contained nervousness. He was cute, though. She couldn’t deny that.

“I’ll tell you what. How about you give me your number, and I’ll think about it?”

His smile grew even wider. He hurriedly scribbled down his number on the back of his business card and handed it to her.

“I usually get off around six,” he said.

“I’ll think about it,” she answered.

And she had thought about it. For two days she thought about it. She hadn’t realized it going into the job, but dating options for a female cop are few. She could date other cops, and a lot of girls did, but there wasn’t a sewing circle anywhere that could gossip like a bunch of cops, and the girls who did date their fellow officers quickly developed reputations as sluts, or bitches, or psychos, or whatever, whether it was deserved or not.

The other option, dating a guy from outside the department, a civilian, was harder than it sounded. Most of the men she met came into her sphere because they were in the process of committing some kind of crime. And even if they weren’t doing something illegal, finding time to go out with them around the demands of a rotating police schedule was nearly impossible. Plus (and this wasn’t obvious, but it was something that nearly every female officer she knew had experienced) most men who weren’t cops were intimidated by a girl who walked around with a gun in her purse . . . and who knew how to use it.

But Jim Norton wasn’t that way. He didn’t seem intimidated by her at all. He’d made her feel special from the first moment he’d tried his dorky lines on her, and in the end, she’d called and asked him out. They were married eight months later.

Memories of those early days together always made her smile, but unfortunately her reverie didn’t last long, for just then the shutters started to rattle. Another blast of rain and wind swept over the house, carrying with it a train wreck sound and the horrible feeling that God’s shadow was passing overhead.

“I need to go get her,” Eleanor said.

Jim, who had rocked back on his haunches, a corner of Madison’s sleeping bag still in his hand, nodded.

“Wait for this one to pass first,” he said.

“Mom.”

Eleanor looked at her daughter. The smile and the giggle were gone. For the first time there was fear in the girl’s eyes. The knowledge that something big and angry had them in its sights was finally starting to sink in.

Eleanor crossed the room and put her arms around her. “I’m gonna bring Ms. Hester here with us,” Eleanor said.

“Mom, you can’t go out in that.”

“Sweetie, we can’t leave her to face that alone. It’ll stop in a second. I won’t be gone long.”

“Promise?”

Eleanor pulled her daughter close. “I promise.”

Five days earlier, a Category Three hurricane named Gabriella had zeroed in on Matagorda Bay, just south down the coast from Houston. Houston was expected to get the dirty side of the storm, and all the newscasters prophesied a Katrina-like disaster. A massive evacuation was ordered. Nearly four million people fled the Houston area, turning the highways that led to San Antonio and Dallas into parking lots. For two days, the city of Houston turned into a ghost town.

But Gabriella didn’t cooperate.

She fizzled to a weak tropical storm while still at sea, and when she made landfall, all she’d been able to muster was a good soaking for the grass and a couple of broken windows along the coastline.

Houstonians returned home, resentful of the ordered evacuation. It was why so many had ignored the current order to evacuate now that Hector was on the way.

In the back of her mind, Eleanor had hoped that Hector would blow itself out the same way Gabriella had, but when she stepped out her front door, all hope of that disappeared from her mind. Even the biggest trees were tossing wildly back and forth. Trash and leaves filled the air. Ocean-scented rain moved across the lawn in silvery, wind-blown curtains. A rainbow-colored canopy from a child’s backyard swing set tumbled down her sidewalk.

On the other side of the street, the pecan trees that surrounded Ms. Hester’s house were slamming against her kitchen wall, stray limbs raking across the roof, kicking up shingles and sending them airborne on the wind like playing cards.

“You stay here,” Jim said. “I’ll go get her.”

“No,” Eleanor said, barely aware that she was using the harsh, clipped tone of her cop’s voice. “Let me. You stay with Madison.”

He looked indecisive, as though he was torn between his male instincts to take the risk and his knowledge that she was the one trained for this kind of thing.

“I’ll be okay,” she assured him, but without softening her tone. It was best not to give him a chance to finish the debate, so that he wouldn’t talk himself into doing something stupid. There was no time for that. “You stay with Madison. Keep her calm.”

And with that she ducked her head and stepped off the porch and into the wind.

The rain needled at her skin. Standing upright was harder than she expected. She had to tense the muscles in her thighs just to keep her balance. The ground was spongy beneath her feet. An inch of water stood on the ground, and everywhere she looked she saw the crawfish that had washed up from Bays Bayou scurrying through the grass.

To the south was a bank of black clouds that stretched across the horizon like an angry, roiling cliff. Charleston Street stretched a good half mile out in front of her before curving out of sight. Beyond the curve was the flat greenish-black surface of Bays Bayou, now flooding the areas adjacent to its banks, and beyond the water was an industrial park of concrete and glass buildings. From where she stood she could just see a line of those buildings disappearing beneath the bottom of the storm wall. To Eleanor, it looked like they were being eaten.

She was too stunned to move. She stood there, mouth open in awe, watching the approaching monster.

A loud crack to her right snapped her out of the moment and she turned just in time to see a large limb from one of Ms. Hester’s pecan trees come crashing down on the corner of the house. It twisted in the wind, sagged, then scraped down the side of house, ripping the plywood covers Jim had put over her windows from their brackets. The glass behind the plywood exploded with a series of muffled pops.

But the tree didn’t stop moving. Its dense cluster of leaves caught the wind like a sail and pulled it down the length of the house, tearing down a section of the wall as it tumbled away from the approaching storm.

“Oh my God,” she said.

She couldn’t believe what she was seeing. In a crazy, terrible, unreal way, it looked like the house was being zippered open by an old-style can opener, the pecan tree shredding the wooden siding with unbelievable speed.

“No!” she shouted.

The tree tore free of the house and sailed down the street as though it were being dragged behind an invisible truck.

Eleanor watched it go, then ran to the house.

She pounded on the front door, kicked it with everything she had, even threw her shoulder into it. “Ms. Hester! Betty Jo! Open the door. It’s me, Eleanor.”

Nothing.

She threw her shoulder at it one more time, then ran for a damaged section of the wall, shielding her face from the wind with her arm as she searched for a way inside.

The gash left by the pecan tree had torn the kitchen wall in half. Shredded electrical wires extruded from the lath, their jagged ends reaching for her like dangerous fingers. The wind was roaring in her ears. The air around her smelled of musty insulation and ocean rain and crushed vegetation.

“Ms. Hester?” she called out. “Can you hear me?”

Nothing.

She was really scared now. Her face hurt from the pelting rain. You gotta get inside right now, she thought. There’s no time. Go, go, go!

Eleanor climbed over the jagged fragment of kitchen wall. Inside, the house was a mess. Water was already pooling on the living room floor and dripping down the walls. Debris was strewn everywhere. A large recliner was upside down against the back wall of the living room, papers and pictures swirling around it.

Eleanor ran for the hall closet. Back in May, when all the literature about hurricanes had first started appearing in the papers, Eleanor had told Ms. Hester to take shelter there if she was trapped at her house during a hurricane. She threw open the door, but the closet was empty.

A sudden surge in the wind threw her against the wall, yanking the doorknob out of her hand.

“Ms. Hester?”

Her only answer was the wind ripping into the house, tearing the walls apart.

From somewhere behind her she heard a loud snap, followed by the sound of walls breaking apart.

No, she thought, shaking her head. That is not possible.

But it was happening. The house ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...