- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

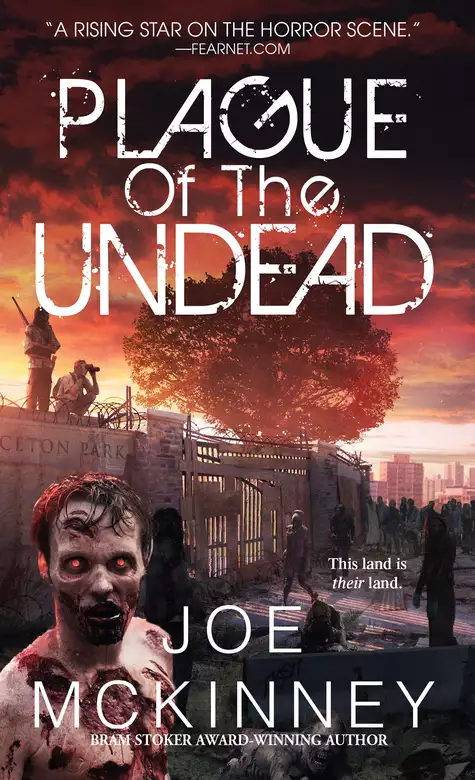

Synopsis

For thirty years, they have avoided the outbreak of walking death that has consumed America's heartland. They have secured a small compound near the ruins of Little Rock, Arkansas. Isolated from the world, they have remained blissfully unaware of what lies outside in the region known as the Dead Lands. Until now.

Led by a military vet who's seen better days, the inexperienced offspring of the original survivors form a small expedition to explore the wastelands around them. A biologist, an anthropologist, a photographer, a salvage expert-all are hoping to build a new future from the rubble. But the infected are still out there. Stalking. Feeding. Spreading like a virus. Wild animals roam the countryside, hunting prey. Small pockets of humanity hide in the shadows: some scared, some mad, all dangerous. This is the New World. If the explorers want it, they'll have to take it. Dead or alive.

Release date: October 7, 2014

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Plague of the Undead

Joe McKinney

For the last two weeks, ever since her husband’s sentence was handed down, Amanda Grieder had been living in the street outside her husband’s cell, crying for someone to come to their senses and show a little mercy. It was February, and it was cold, and most mornings found her hair and clothes crusted with ice. She’d stopped eating, stopped taking care of herself. She couldn’t be consoled. Her friends tried to get her to go home, even tried to pick her up and carry her home at one point, but she would have none of it. After that, whenever they tried to touch her, she fought them, and then the screaming and wailing would start up again and it would carry through the whole town like a sickness, laying everybody low. There was talk that the law should make her leave, do something with her, for her own good, for everybody’s peace of mind, but so far Sheriff Taylor had held off doing that. Jacob didn’t understand the old man’s reticence, but he knew Sheriff Taylor had his reasons. He always did.

Jacob braced himself as he turned the corner onto Jackson Avenue, where Amanda had set up her temporary residence. He said a silent prayer that he wouldn’t have to deal with her again today. Every morning he had to pass the little makeshift shelter where she kept watch. He’d try to walk by unobserved, but then she’d see him, and no matter how cold or hungry she was, no matter how shredded her voice was from howling all the day before, she always seemed to have a little extra just for him. She’d get up from the sidewalk and rush at him, screaming that he’d made a mistake, that he was wrong about her husband. As sick as her accusations made him feel, he knew he wasn’t up for enduring that gauntlet today. Not today, not the day of the execution. He just didn’t have it in him.

But to his surprise—and this shamed him, for he was relieved—she wasn’t there. The blankets and baskets of food well-meaning folks had brought for her were still there, but she was gone.

He let out the breath he’d been holding and tried to collect himself, but his nerves were a jangled mess. His skin felt hot one moment, cold the next. His stomach was twisting into knots. He had the jitters, like he’d drunk too much coffee on an empty stomach. For two weeks he’d felt this way, and he suspected it was making him sick. Not only heartsick, but actually physically ill.

But sick as he was, he had to keep moving. If he stopped, he’d lose his nerve. Looking into himself, he knew that. The way things were piling up inside his head, all it would take would be to stop moving. If that happened, he’d likely as not turn tail, run home, and hide his head in the toilet as he vomited away his jitters. If, indeed, that was even possible. So he ducked his head against the cold February wind and shoved his hands into his pockets and slipped into the constabulary office like a villain.

It was early, and Steve Harrigan was the only one in the office. He was standing over by the filing cabinets, and when he heard the door and saw Jacob standing there he looked genuinely surprised. “Wasn’t expecting to see you this morning,” he said.

Jacob nodded. “Where’s the bike checkout log?”

Harrigan studied the younger man for a long moment. He closed a metal drawer and it shoved in place with a heavy clank. Harrigan gestured toward the back wall with his chin. “Should be over there on the shelf, behind Harris’s desk.”

Jacob crossed to the shelf the older deputy had indicated. The bike log was a red, hardbound memo book that was almost as old as Jacob was. There were entries going back as far as his school days, when he was taking his first lessons in the Code he now enforced. He turned to the back and quickly scribbled his name on the next open line.

“Gonna try to clear your head?” Harrigan said.

“I was thinking of going for a ride, yeah. I thought I’d go check on the new construction over on the east wall.”

“Still draining the wetlands, from what I hear.”

Jacob nodded. “Where’s Taylor? I noticed Amanda’s gone.”

“He’s with her in his office.”

“Oh, God, really?”

“Yeah. They’ve been in there for about an hour now. She finally stopped crying just a bit ago. Poor woman, she’s coming apart at the seams.”

“Is he gonna let her be in the Square today?”

“Can’t tell her no. It’s her right under the Code.”

Jacob could tell the older deputy was sizing him up. Harrigan was a real cop, trained in the old ways, from before the world fell apart. Not like Jacob, who had sort of stumbled into the role of chief deputy, a kid trying to figure it out as he went along.

Harrigan was an affable, lanky man with pale skin and thin gray hair and liver spots on his face, always quick with a smile. But of course that smile was gone now. He put the file he was holding on his desk, lit a candle, and shook the match out. “We’re almost out of these,” he said, and dropped it into an ashtray. “The ones they make over at the school don’t hardly ever work. We go through ’em so fast.”

“I’ll tell Frank Hartwell to get some more next time he’s outside the walls.”

Jacob put the ledger back on the shelf and turned to leave. He was almost to the door when Harrigan called after him. “Hey, Jacob, a moment.”

Jacob stopped in the doorway, looking back at him over his shoulder. “I’m not much in the mood for a speech, Steve, if you don’t mind.”

“No, I bet not. But I know this is tearing you up inside. You wouldn’t be half the man I know you to be if it wasn’t.”

“I don’t feel like a good man right now, Steve. All I want to do is go stick my head in a hole and hide.”

“Same thing Arthur went through when he had to do it.”

“And how did Arthur handle it?”

“Spent the whole morning throwing up.”

Jacob nodded. “Sounds about right.”

“Nobody said it was easy.”

“Easy,” Jacob said, and laughed in disgust.

“This is the right thing to do, Jacob. I believe that. I believe in the Code. It’s us against the world. We have to trust each other. Any man who steals from his brother breaks that trust. And that man has to die.”

“That’s the same thing you told me when you were teaching my Code class back in school. You need to get a new line.”

“It’s not a line, Jacob. It’s what I believe in. It’s what everybody in this town believes in. The Code is hard sometimes, but it’s what keeps us alive. Think on that while you’re riding.”

The older deputy didn’t cow Jacob, not these days. In his youth, all the First Generation had seemed hard and determined, like iron, but he was thirty-five-years old, and he’d faced most of them in council meetings and in the living rooms of their homes when things went wrong. So Harrigan’s words didn’t rattle him. They only made him tired. He’d heard the same thing every day of his life since the time he was old enough to understand what was being said to him. And he’d always thought he believed it. But now that he was going to have to kill a man he’d known since they were kids, belief came a lot harder.

“I’ll be riding the east wall,” he said.

Jacob got one of the bicycles from the shed and headed east, into the sunrise.

During the summer, Arbella felt crowded. Nearly ten thousand people, all of them crammed together in a town that had once housed barely four thousand before the First Days. Many of the First Generation families still had their own residences, but elsewhere in the town, as many as three families shared a single three-bedroom home. To meet the rising demand for food, nearly every lawn had long since been turned into a vegetable garden. The stoplights had come down because there weren’t any more cars to stop, just young children with sticks and dogs by their sides driving herds of goats or sheep into the markets in the center of town. The Pecan Valley Golf Course out on Southton Road was now a dairy farm. The peach orchards out on Interstate 55 were now home to thousands of pigs and turkeys and chickens. And even the wetlands that stood between the town and the river to the east were being turned into cropland. But with the coldest days of winter upon the town, there wasn’t much going on. Most of the shops were still dark. Jacob saw lamplight in a few windows, but only a few. Save for the horse-drawn milk wagons coming up from the dairy, he had the town of Arbella pretty much to himself. Just his thoughts for company.

Steve Harrigan was right of course about the Code. Jacob hated how simply he’d put it, because it made the Code sound like a platitude, but for all that, he was right. The Code really did keep them alive. It was their moral core, the center around which their entire society orbited. Arbella was an island in a world that quite literally wanted to devour them, and the Code they lived by helped them to not only survive, but thrive in that world. They worked for each other, giving freely of their skills and their goods, so that all had a chance to survive. You had to trust your fellow citizens. You had to believe that, together, you were greater than the dangers of the wasteland. You had to believe it, because anything else meant surrendering to the fear and pain and death that lurked beyond the walls. Jacob’s thoughts turned to Jerry Grieder, Amanda’s husband. It wasn’t just some stolen jewelry, he told himself, thinking of Amanda’s pleas for mercy for her husband. Jerry hadn’t just stolen some young girl’s beloved locket, but rather the trust from the entire community. Jerry Grieder wasn’t just guilty of burglary; he was guilty of contaminating everything the people of Arbella stood for, what kept them alive.

Jacob pedaled faster, the biting wind on his face the only thing that kept his tears from bursting loose. He was almost grateful for the sting on his cheeks. It felt good to hurt, because it was the only thing he could think of to convince him that he was still human. He’d known Jerry Grieder since they were children. How in the hell was he going to put a gun to the man’s head and pull the trigger? He just didn’t think he was going to be strong enough.

Gradually he tired of the hard pedaling and coasted, letting the bike carry him along. His face and knuckles were raw with the cold, but he didn’t care. He kept going, watching the sleeping buildings, thinking about his home.

Thirty years ago, before the First Days, Arbella was a little town nestled comfortably on a bend of the Mississippi River known as New Madrid, Missouri. Sheriff Taylor led the First Generation, a little over a thousand of them, out of Arkansas and into Missouri, fighting and dodging the undead the whole way. They happened upon New Madrid and found the place deserted. They put makeshift barricades up around the town, and over the course of four months fought the zombie hordes to a standstill.

In honor of their victory they renamed the town Arbella, after the flagship of Governor John Winthrop’s Puritan fleet that had settled the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. It was from the deck of that ship that Winthrop delivered his famous “City Upon a Hill” sermon, and it was in that same spirit of shining a light on a cold and hostile world that Jacob’s mother, and the other members of the First Generation, turned an abandoned hamlet into a home.

The barricades became sturdy twenty-foot walls of wood and razor wire, wide enough for the lookouts and the sharpshooters who continued to guard against the zombies that sometimes wandered too close. The empty churches were turned into grain silos. Dairy cows took over the golf course. Babies were born. Lives were lived. And very quickly, Arbella turned into a self-sufficient island of peace in the wasteland.

Jacob was three when that happened.

He didn’t remember the time before the First Days. All his life had been spent in and around Arbella, watching it grow, watching it prosper, watching it swell at the seams from the bounty the town made. The original thousand members of the First Generation had since had children, and taken in those healthy few who now and then happened upon the town and were willing to work hard. In the blink of an eye one thousand became ten thousand, and more were being born every day.

Jacob watched daylight spread over the rooftops of the town and over the gardens. It dappled the metal roofs of the water purification stations like molten copper, and in that moment, Jacob swelled with pride for his town. True, he wasn’t there at the fight that ended the First Days, but he’d helped to build Arbella. He’d served it as a citizen, and as a member of the salvage teams sent out into the wasteland to gather the things the town needed, and most recently, as the chief deputy of its constabulary. He was thirty-five years old, and in line to take over the leadership of Arbella when the First Generation was ready to pass that baton along. In that moment, proud of his town and of himself, he found it easy to believe in the Code again. Its values were his values, and the town it protected his home.

But the quiet didn’t last. A raid siren filled the cold morning air, sudden and shrill.

Jacob was on Oberlin Street at the time, near the intersection with Yale, the east wall still about three blocks away. Within seconds of the siren going off the streets filled with people. Men and women came down from their porches to the edges of their gardens and looked at one another. The raid sirens were hardly used anymore, for there hadn’t been a sizeable zombie horde at the gates for more than twelve years.

“Jacob, what is it?”

He turned and saw Linda Moffett standing by her front gate, a dishtowel in her hands.

He was about to tell her he had no idea, when the hue and cry came down the street: “It’s Jim Laymon up on the wall!”

A woman ran into her yard. “Somebody make him kill that noise!”

“He’s lost his mind,” somebody yelled back at her.

Jacob stood up on his pedals and rode hard for the wall. A crowd had gathered in the street beneath Jim’s lookout station, and it was getting bigger by the moment. Some were yelling questions at him, others frantically trying to get him to cut out the noise. Nobody seemed to be getting his attention.

Jacob saw a ladder leaning against the fence and scaled it.

Jim was the very model of the Code. At eighty-four, he was one of the oldest citizens of Arbella, yet he manned a lookout post on the wall three days a week. Everybody works; everybody pulls their weight. That was the essence of the Code, and Jim lived it.

He had set up a comfortable workstation for his day. There were jugs of water at his side, a basket of food a little ways off. His binoculars hung from a nail on the railing. There was even an umbrella, for later in the day, when the sun came out. He had heavy blankets over his shoulders and across his lap, though now the blankets were coming off as he leaned over the raid siren, working the hand crank with everything he had.

Jacob ran over to him and put a hand on the crank to stop it.

“What are you doing, Jim? Stop it.”

“Look!” he shouted toward the river.

It was a few hundred yards away. Jacob could smell the warm, sweet decay of its muddy banks and the upturned earth where the dredging teams were draining the wetlands just outside the wall. The clatter coming up from their pumper trucks was tremendous. But he didn’t see what Jim wanted him to see.

Not at first.

And then he saw movement in the darkness down by the river.

Jacob squinted, straining his eyes to see into the shadows. “Oh, no,” he said.

From below, someone shouted, “Hey, Jacob, what’s wrong?”

He leaned over the railing and yelled at the crowd, “Zombies on the wall! I need sharpshooters up here now!”

Nobody moved; nobody spoke. They just stared up at him in shock.

“Sharpshooters!” he said. “Send up the alarm.”

It took a moment, but once a few members of the crowd scurried off, the others followed suit. Jacob turned back to Laymon.

“Where’s their sentry? Why aren’t you using your mirror to signal them?”

“They ain’t got one.”

“What?”

“They ain’t got a sentry.”

“What do you mean? Where is he?”

“They ain’t got one. Just workers.”

That was a huge violation of protocol. Nobody but salvage teams ever went beyond the wall without sentries to cover their backs. That was never supposed to happen.

“I need to get down there,” Jacob said.

He pulled the ladder over the wall and hurried down it. When he was on the ground again, he pushed the ladder into the grass and ran for the workers.

The noise from their pumper trucks was deafening, and all the men wore ear protection. It was no wonder they’d failed to hear the warning siren. Their foreman was leaning over a table, looking at a map scroll. Jacob grabbed him by the shoulder and spun him around.

“Shut off those machines!” he yelled. “Shut ’em down!”

He heard Jacob, Jacob knew he did, but he didn’t understand. Jacob pointed at the machines and drew his hand across his throat. “Shut ’em down! Right now!”

He still didn’t understand.

Jacob grabbed him by the shoulder, shoved him toward the front of one of the trucks, and pointed toward the river.

A herd of zombies was coming up from the water’s edge, pulling themselves along through thick mud.

“Shut off your machines!” Jacob yelled.

Now he understood. The foreman jumped into the cab of the nearest pumper truck and hit the kill switch. As the pumps wound down, workers looked up from their hoses in confusion. The foreman made frantic X’s with his arms across his chest, and within seconds, the other three trucks went silent.

Men turned from their work, pulling the earplugs from their ears.

“Go to the wall,” Jacob shouted. He pulled his pistol. “Go, I’ll cover you.”

They seemed as confused as the foreman had been until Jacob leveled his weapon at the approaching forms materializing out of the fog that clung to the river’s edge.

Once the moaning started, they all ran.

The trucks had big floodlights mounted on top of their cabs. They threw a blinding ring of light on the area the pumpers had been draining, and it kept Jacob from seeing anything beyond the light with any sort of clarity.

A figure staggered into view less than twenty yards away. More stepped out of the fog on either side of him.

Jacob raised his pistol at the first zombie and, for a moment, locked up in fear. He’d seen zombies before. More than most, in fact. During his time with the salvage teams he’d seen at least a hundred. He’d even put down a few. But he’d never seen one like the undead thing facing him now. It was covered in river scum, mud dripping off its frame. Jacob couldn’t tell if it was man or woman, much less what color the thing’s skin had been. Black, white, Hispanic, Asian . . . he had no clue. When they decay that badly, they all looked the same. All Jacob saw was river gunk dripping off a skeleton wrapped in a wrinkled leather sheet. The thing could barely walk. With every step, it looked like it might collapse. But walk it did, and it closed the distance between it and Jacob soon enough.

The zombie raised its hands to claw at Jacob’s face and in that moment he got a glimpse of mud-covered bone showing through the decayed skin of its arm.

Jacob raised the pistol to its face and fired.

The thing’s head snapped back, and the next instant it folded to the ground in a heap.

“Whoa!” he said, and clawed backwards toward the lit work area.

More zombies staggered into the ring of light on rickety legs, all of them covered in river scum, all of them badly decayed. Jacob scrambled to his feet and was about to turn toward the wall when he heard someone yelling for help.

It was an eighteen-year-old kid named Winston Roberts that he had arrested at least half a dozen times for fighting and public intoxication. Roberts was tangled in a nest of heavy hoses and wires, like a man wrestling with a giant snake.

Jacob ran over to him and helped him climb loose of the hoses. “Go that way,” he said, pointing with his gun toward the wall.

“What the hell, man? What is this shit?”

“Go!” Jacob said. “Get moving!”

Some people, even when it’s for their own good, just won’t take orders. Jacob had just pulled him from a muddy pit of hoses. He could see the zombies closing in around him. But all the kid heard was a cop telling him what to do. It was like his mind switched off. He bowed up like he wanted to fight him. Jacob turned and shot two of the things in the head, felling them at his feet. That was what it took to knock some sense into Roberts. He scrambled out of the mass of the hoses, the horror plain on his face.

“Go!” Jacob yelled. “Get to the wall!”

In the mud were the two zombies he’d just put down.

The others moaned as they closed in around him. But Jacob didn’t move. He was still staring at the two zombies he’d put down. He’d never seen any so badly decomposed before. There barely seemed to be enough muscle tissue remaining to haul the things around.

A muddy hand fell on his back, grabbing at his shirt.

Jacob yelled and spun away from it, breaking the zombie’s fingers as he twisted.

He tripped over a hose and nearly fell. His right foot came down hard in the mud and he sank up to his calf. From the wall he heard people screaming, and all around him, the bloodcurdling moans of the dead.

Mired in the freshly turned river soil, Jacob pulled on his leg with everything he had. “Come on, come on!” he muttered.

One more pull and he was free, his foot coming loose without his boot. But there was no time to go back for it. The workers were gathering at the base of the wall, pushing the ladder back into place. Most of the zombie herd was closing in on Jacob’s position, but a few were making their way toward the panicked group of workers. He had to cover them.

Jacob ran for the wall. The workers were shoving each other and yelling.

“One at a time,” Jacob said. “Move quickly. I’ll cover you.”

He stepped away from the crowd, putting himself between the wall and the approaching zombies. There were more than he’d first thought, sixty or seventy at least. Most were still recognizable as men or women, but some were barely more than skeletons, with only scraps of muddy cloth left of their clothes.

Jacob looked down at the pistol in his hand and tried to remember how many shots he had left. There hadn’t been enough ammunition for him to top off his magazine before he went in to work, and he’d fired four rounds already.

“You guys need to hurry up!” he yelled over his shoulder at the workers.

They were climbing the ladder three at a time now, and Jacob could see it shaking and bowing under their weight.

He turned back to the approaching zombies, took a deep breath, and shot the two nearest him. A third put on a sudden burst of speed and charged out of the herd. Startled, Jacob wheeled on the woman and fired without aiming. The bullet hit the top of her head and made it snap back, so that she was looking up at the sky. A wet chunk of her scalp flew out behind her. She stopped in her tracks, and then slowly lowered her gaze on Jacob again.

For the second time that morning, he froze.

Her eyes were dead and empty, yet somehow lit with an insane and insatiable rage. Or was it hunger? He couldn’t say for sure. He only knew that her eyes held him transfixed, like a rabbit caught by a snake’s stare.

Shouting from above shook him loose of the thing’s stare.

He glanced up and back. The last of the workers were on the ladder now, and Jim Laymon was motioning for him to come up.

“We got sharpshooters on the way,” he said.

Jacob didn’t need to be told twice. He turned back to the woman he’d just shot, aimed carefully at her nose, and put her down. Then he turned and ran for the wall.

He went up the ladder in a daze. Somebody grabbed him and pulled him out of the way while someone else lifted the ladder over the wall.

Dale and Barry Givens, two of Arbella’s best snipers, were standing there, rifles at the ready.

“Can we take ’em down now, boss?” Dale said.

Jacob stared at him for a moment, confused. Then he remembered they needed the approval of the constabulary to fire outside the walls. The noise was the big issue. The town had learned over the years that noise was the enemy when dealing with the undead. It brought them out of the woodwork.

Jacob didn’t feel much like a cop. His chest was heaving. He was rattled through and through. He was covered in mud and only wearing one boot. He holstered his weapon and tried to calm the wild bird beating against the inside of his rib cage.

But when he spoke, the definitive note of command was back in his voice.

“Yeah, take ’em down.”

An hour later, Jacob was back at the office, sitting in front of a blank sheet of paper, trying to figure out what to say in his report.

The workers should have had a sentry in place. At least one. Protocol called for one armed guard for every ten men working on a project outside the wall, and not following that protocol was just a stupid error. There was no other way to describe it. Even if they hadn’t been able to find a sharpshooter to do the job, the foreman should have at least used one of his crew. After all, every man and woman in Arbella knew how to handle a gun. They learned as children, as part of their schooling. It wasn’t worth risking everybody’s life just to finish a job quicker. Somebody was going to get it over this, and Jacob had his money on the foreman.

But it wasn’t the lack of leadership that really bothered him. It was the zombies that he’d shot. The amount of decay he’d seen was way beyond anything he’d ever seen before. Back when he was training to go outside the walls with the salvage teams, he’d been shown pictures of zombies, and told what to look for. Some of the old ones could look like moldering corpses rotting away in doorways, their skin so cracked and dry, their muscles so atrophied, they looked more like hunks of beef jerky than zombies. But they could get up. They could go from dormant to attack mode in the time it took you to turn your back on them. And they were every bit as lethal as the freshly turned ones.

Somebody had asked the trainer how old a zombie could get before they finally rotted away, and the trainer had said she didn’t know. Nobody knew for sure. Six years maybe, maybe even eight, if they lived in the right climate and didn’t tear themselves apart while hunting their prey.

Flesh could only last so long, after all, even with the help of CDHLs.

Back in school he’d learned about the First Days. The zombies weren’t the product of terrorism or a rogue virus or junk DNA, but the entrepreneurial desire to make vegetables last longer on the shelves.

China, his teachers said, had experimented with pesticides and preservatives, looking for a way to make their domestically grown foodstuffs stay fresher longer. Their efforts culminated in a family of chemical compounds known as carbon dioxide blocking hydrolyzed lignin, or CDHLs. The Chinese tested it, claimed it was safe, and spread it over everything that grew.

The compounds were tested, and eventually vetted by the FDA. Once the Food and Drug Administration declared CDHLs safe for human consumption, they spread across the globe. Suddenly plums could stay purple and juicy for months at a time. Roses never wilted. Celery, carrots, even lettuce could sit on a grocery store shelf for weeks and still look as fresh as the day they were harvested. Even bananas could stay traffic light yellow for three months.

The blood banks were the first to report signs of trouble. CDHLs didn’t appear to break down in the human bloodstream the way they did in plants. There was no cause for immediate worry, except that blood supersaturated with CDHLs seemed to stay unnaturally healthy and vital well beyond any sort of conventional measure.

In hindsight, Jacob’s teachers had said, it should have been obvious.

CDHLs were linked through study after study to hyperactive behavior in children.

Unfocused aggression was a common symptom of adults of middle age. Housewives killing their children and waiting at the kitchen table with a butcher’s knife for their husband’s return from work shouldn’t have seemed like business as usual.

And yet it was.

The First Days had crept up on them like a thief in the night, even though it should have been obvious what the CDHLs were doing to them.

The trouble started in China. The central cities of Wei-shan and Qinghai were the first to erupt in anarchy. The Chinese, much to their credit, made no attempt to cover up what was going on. Video streamed out to every news service and website, and those first glimpses of the dead crowding the streets were terrifying beyond all reckoning.

From Central China the zombie hordes spread to the more densely populated coastal cities, and by that point there was no saving mainland Asia. Everyone who could evacuate did. They fled to Japan and Australia, some even to the United States, but many millions were left behind to be devoured. There were simply too many to save.

The rest of the world watched it happen, believing that their quarantine efforts had worked. But of course the quarantine effort was merely shutting the barn door after the cow was already out. The culprit, the CDHLs were already in the ground, already

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...