- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

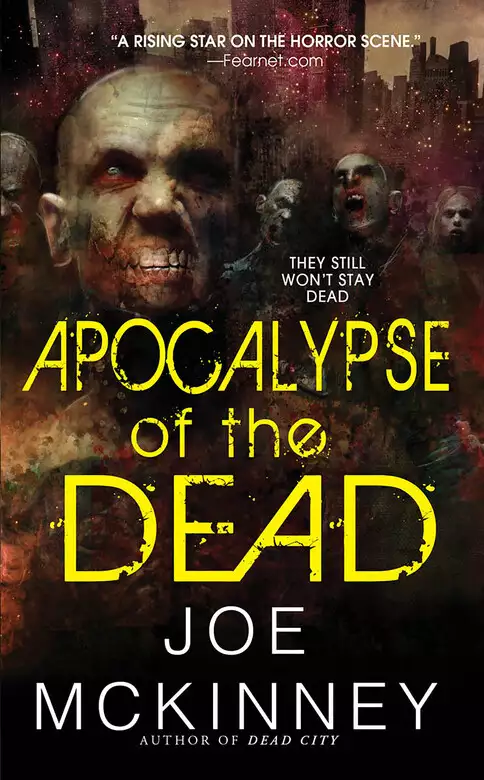

Synopsis

And the dead shall rise...

Two hellish years. That's how long it's been since the hurricanes flooded the Gulf Coast, and the dead rose up from the ruins. The cities were quarantined; the infected, contained. Any unlucky survivors were left to fend for themselves. A feast for the dead.

And the living shall gather...

One boatload of refugees manages to make it out alive-but one passenger carries the virus. Within weeks, the zombie epidemic spreads across the globe. Now, retired U.S. Marshal Ed Moore must lead a group of strangers to safety, searching for sanctuary from the dead. A last chance for the living.

Let the battle begin.

In the North Dakota grasslands, bands of survivors converge upon a single outpost. Run by a self-appointed preacher of fierce conviction-and frightening beliefs-it may be humanity's only hope. But Ed Moore and the others refuse to enter a suicide pact. They'd rather stand and fight in the final battle against the zombies. An apocalypse of the dead.

Release date: November 1, 2010

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 512

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Apocalypse of the Dead

Joe McKinney

Flying over the flooded city, Barnes remembered what it was like after the storm, all those bodies floating in the streets, how they had bloated and baked in the sun. He remembered the chemical fires from the South Houston refineries turning the sky an angry red. A green, iridescent chemical scum had coated the floodwaters, making it shimmer like it was alive. That mixture of rotting flesh and chemicals had produced a stench that even now had the power to raise the bile in his throat.

What he didn’t know—what nobody knew, at the time—was the awful alchemy that was taking place beneath the floodwaters, where a new virus was forming, one capable of turning the living into something that was neither living nor dead, but somewhere in between.

Before the storm, Barnes had been a helicopter pilot for the Houston Police Department. Grounded by the weather, he’d been temporarily reassigned to East Houston, down around the Galena Park area, where the seasonal floods were traditionally the worst. The morning after the storm, he’d climbed into a bass boat with four other officers and started looking for survivors.

Everywhere he looked, people moved and acted like they’d suddenly been transported to the face of the moon. Their clothes were torn to rags, their faces glazed over with exhaustion and confusion. Barnes and his men didn’t recognize the first zombies they encountered because they looked like everybody else. They moved like drunks. They waded through the trash-strewn water, stumbling toward the rescue boats, their hands outstretched like they were begging to be pulled aboard.

The city turned into a slaughterhouse. Cops, firefighters, National Guardsmen, and Red Cross volunteers went in thinking they’d be saving lives but emerged as zombies, spreading the infection throughout the city. Barnes considered himself lucky to have escaped. When the military sealed off the Gulf Coast, they’d trapped hundreds of thousands of uninfected people inside the wall with the zombies. Barnes emerged with his life, and his freedom; nearly two million people weren’t so lucky.

And with the rest of America in an unstoppable economic nosedive after the death of its domestic oil, gas, and chemical industries, he considered himself lucky to get a job with the newly formed Quarantine Authority, a branch of the Office of Homeland Security that was assigned to protect the wall that stood between the infected and the rest of the world.

But all that was two years ago. It felt like another lifetime.

Today, his job was a routine sweep with the Coast Guard. Earlier that morning, a surveillance plane had spotted a small group of survivors—known as Unincorporated Civilian Casualties by the politicians in Washington, but simply as “uncles” by the flyboys in the Quarantine Authority—working to wrest a wrecked shrimp boat loose from a tangle of cables and nets and overgrown vegetation. Most of the boats left in the Houston Ship Channel were half-sunken wrecks. And what hadn’t sunk was hopelessly, intractably mired in muck and garbage. There was no chance at all that a handful of uncles could get a boat loose from all that mess and make a run for it. And even if they could, they’d never be able to beat the blockade of Coast Guard cutters waiting just off shore. They’d be blasted out of the water before they lost sight of land. But the Quarantine Authority’s mission was to make sure nobody escaped from the zone, and so the order had gone out, as it had numerous times before, to mobilize and neutralize as necessary.

Now, along with three other pilots from the Quarantine Authority, Barnes was slowly moving south toward the Houston Ship Channel. Once there, they’d rendezvous with the boys from the Coast Guard’s Helicopter Interdiction Tactical Squadron, known as HITRON, and act as forward observers while the H-Boys took care of any survivors who might be trying to escape to the Gulf of Mexico.

“Good Gawd, would you look at them?” said Ernie Faulks, one of the Quarantine Authority pilots off to Barnes’s right. In the old days, Faulks had made his living flying helicopters back and forth from the oil rigs just offshore. He was an irredeemable redneck, but cool under pressure, especially in bad weather.

Barnes glanced up from the ruins below and saw a string of seven orange-and-white Coast Guard helicopters closing on their position. Even from a distance, Barnes could pick out the silhouettes of the HH-60 Jayhawks and the HH-65 Dolphins.

“You know what those babies are?” said Paul Hartle, a former HPD pilot and Barnes’s preferred flanker. “Those are chariots of the gods, my friend. Ain’t a helicopter made that can hold a candle to those bad boys.”

“I’d love to fly one of them things,” answered Faulks. “I bet they’re faster than your sister, Hartle. Sure are prettier.”

“Fuck you, Faulks.”

Faulks made kissy noises at him.

“All right, guys, kill the chatter,” Barnes said.

Technically, he was supposed to write up the guys when they cussed on the radio, but he let it slide. A little friendly kidding was good for morale. And besides, as pilots, Barnes and the others were seen as hotshots within the Quarantine Authority. They were held to different standards, given special privileges, looked up to by the common guys on the wall. Being pilots, they had to do more, take bigger risks. It was why all these guys loved flying, why they kept coming back.

But in every profession there is a hierarchy, and while Barnes and his fellow Quarantine Authority pilots had a firm grip on the upper rungs of the status ladder, the very top rung was owned by the H-Boys from the Coast Guard’s HITRON Squadron. Originally created to stop drug runners in high-speed cigarette boats off the Florida coast, the H-Boys now did double duty patrolling the quarantine zone’s coastline. They flew the finest helicopters in the military, and their gun crews had enough ordnance at their disposal to turn anything on the water into splinters and chum. The pilots in the Quarantine Authority worshiped them, wanted to be them when they grew up. It was the Quarantine Authority Air Corp, in fact, that had come up with the H-Boys’ nickname.

“Papa Bear calling Quarter Four-One.”

Quarter Four-One was Barnes’s call sign. Papa Bear was Coast Guard Captain Frank Hays on board the P-3 Orion that was circling overhead.

“Quarter Four-One, go ahead, sir.”

“I’d like to welcome you and your men to the show, Officer Barnes. Now, all elements, stand by to Susie, Susie, Susie.”

“Mama Bear Six-One, roger Susie.”

Barnes scanned the line of orange-and-white helicopters until he saw one to the far right dipping its rotors side to side. That was Mama Bear, Lt. Commander Wayne Evans, the senior officer in the squadron and the quarterback for this mission. Once the sweep got under way, he would be the link between the individual helicopters and Papa Bear up in the P-3 Orion. Barnes had worked with Evans before and knew the man had a talent for keeping a cool head and an even cooler tone of voice on the radio when things got sticky.

“This is Echo Four-Three, roger Susie.”

“Delta One-Six, roger Susie.”

“This is Bravo Two-Five, roger Susie.”

The pattern continued down the line of Coast Guard helicopters, each one answering up with their call sign and the code word “Susie,” which was the signal for the sweep to begin.

When they’d all answered up, Mama Bear said, “Quarter Four-One, you and your men drop to three hundred feet and recon the quadrants north of here. Sound off if you spot any uncles.”

“Yes, sir,” Barnes answered.

He gave the orders for his team to drop altitude and spread out over the area. They had done this many times before, and they all knew the drill. And they all knew that the order to sound off if they spotted any uncles was superfluous. The HITRON boys had the finest heat-sensing equipment in the world. Their cameras would spot any bodies down there long before Barnes and his men could. What Barnes and the others were expected to do was identify whether or not the bodies spotted were uncles or zombies. The HITRON boys would only get involved if they had uncles.

But telling the difference under the current conditions wasn’t going to be easy. They had maybe thirty minutes of usable daylight left, and there was a spreading shadow over the ruins that gave everything, even at three hundred feet, a monochromatic grayness.

Barnes recognized the ghostly outlines of Sheldon Road beneath the water. Its length was dotted with tanker trucks and pickups that, even at low tide, were a good five or six feet beneath the surface. He looked east, across a long line of metal-roofed warehouses that shimmered with the reddish-bronze glare of sunset. From frequent flyovers, Barnes knew that at low tide the water was only about two or three feet deep on the opposite side of those warehouses. If they were going to find uncles, that’s where they’d be.

Within moments his instincts proved true. Boats and cranes and even a few larger tankers had been spread by the tides across the flooded swamp that had once been a huge tract of mobile homes. In and among the debris and stands of marsh grass he spotted a large number of people threading their way toward three medium-sized shrimp boats waiting just offshore. One of them already had its engines going. Barnes could see puffs of black smoke roiling up from beneath the waterline.

Several faces turned up to track his movement over their location. He felt like he could see the desperation in their expressions, and he turned away. He didn’t like doing this, but it was necessary.

“Quarter Four-One, I’ve got uncles east of the warehouses.”

There was a pause before Mama Bear answered up. “Quarter Four-One, roger that. You sure they’re uncles?”

Barnes could hear the indignation in the man’s voice. Though they were all on the same team, the H-Boys knew they were the all-stars. Barnes was sure the man was cussing to himself that a Quarantine Authority pilot in a Schweizer POS had spotted their objective before his boys did.

Barnes enjoyed making his reply. “Oh, I’m sure, Mama Bear. I estimate between forty and sixty uncles. Looks like they’ve got themselves three shrimp boats, too.”

There was a pause. Must be on the private line to Papa Bear, Barnes thought.

Finally, Mama Bear answered. “Roger that, Quarter Four-One. Go ahead and give ’em Mona.”

Come again, thought Barnes.

“Uh, Quarter Four-One, I didn’t copy. You said to give ’em Mona?”

“Roger.”

“Mama Bear, did you copy they got three shrimp boats in the water?”

“Roger your three shrimp boats, Quarter Four-One. Echo Four-Three and Delta One-Six will fall in behind in case you need assistance. Now give ’em Mona.”

Give ’em Mona was the strategy most commonly employed by Quarantine Authority personnel when they spotted uncles trying to breach the wall. The expression came from the amplified zombie moans the Quarantine Authority personnel played over their PA systems. The moans carried for tremendous distances, attracting any zombies that might be in the area. Usually, the moans were enough to send the uncles into hiding.

But this isn’t a bunch of uncles throwing rocks at troops up on the wall, Barnes thought. Those people are a viable threat. They have boats. They have boats in the water, for Christ’s sake. You guys are underestimating the situation.

Barnes reached forward to the control panel in front of the passenger seat and flipped the PA system power switch. Instantly, the air filled with a low, mournful moan that Barnes could feel in his chest and his gut.

He hated hearing that noise. He squeezed his eyes shut and tried to block out the images of bodies festooned in the branches of fallen pecan trees, of people screaming for help in flooded attics, of his brother Jack getting pulled under the water by a nest of zombies they’d wandered into when they were less than two miles from safety. But it was no use. Sometimes the images were too powerful, too vivid, and when he opened his eyes, he had tears running down his face.

Barnes didn’t even hear the first shots. He heard a loud plunking sound, like a rock dropping into water next to his ear, and when he looked over his shoulder, he saw a bullet hole in the fuselage.

Missed my head by six inches, he realized.

He heard another sound below him. Glancing down, he saw what appeared to be a faint laser beam between his shins. The bullet had pierced the lower section of the fuselage and entered the supports right below his seat. He had daylight pouring through the bullet hole.

“Quarter Four-One, they got a shooter on the ground!” Barnes heard the panic in his voice but couldn’t fight it.

“Take it easy,” Mama Bear answered.

More shots from below. Barnes could see the man doing the shooting, the bursts of white-orange light erupting from the muzzle of what appeared to be an AK-47.

“I’m hit,” Barnes said.

Instinctively, he pulled back on the stick and started to climb. He couldn’t see the Coast Guard Jayhawk that had moved into position above and behind him, but he heard the pilot’s angry shouts as he turned his aircraft to one side, narrowly avoiding the collision.

“Goddamn it, watch yourself, Quarter Four-One!” the pilot said.

Barnes’s Adam’s apple pumped up and down in his throat as he fought to get himself back under control. He scanned the airspace around him, then made a quick instrument check. Everything appeared to be holding steady.

Out of the corner of his eye, Barnes saw the Coast Guard Jayhawk rotate into position over the uncles below. Barnes could see several uncles shooting now, while farther off, people were jumping into the water and trying to climb aboard the shrimp boats.

“Kill that Mona, Quarter Four-One,” shouted one of the H-Boy pilots.

“Roger,” Barnes answered.

He leaned forward and killed the PA switch. But as he did, he saw a flash of movement that grabbed his attention. A man was kneeling in the shadows between a wrecked fishing boat and what appeared to be the rusted-out pilothouse from a tugboat. He had a long, skinny metal tube over his shoulder and he appeared to be zeroing in on the Jayhawk to Barnes’s right.

Barnes recognized it as an RPG and thought, Where in the hell did the uncles get an RPG? That’s impossible. Isn’t it?

Barnes glanced to his right and saw that the Jayhawk had rotated away from the shooters so that its gun crews could bring their 7.62-mm machine guns to bear on the targets.

“That guy’s got an RPG,” Barnes heard himself say. “Heads-up, Delta One-Six. That guy’s got an RPG. Clear out. Repeat, clear out!”

“Where?” the other pilot asked. “Where? What’s he standing next to?”

“Right there!” Barnes shouted futilely. He was pointing at the man, unable to find the words to describe his position amid all the rubble. It all looked the same.

“Where, damn it?”

But by then the man had fired. Barnes watched in horror as the rocket snaked up from the ground and slammed into the back of the Jayhawk, just forward of the rear rotor. The Jayhawk shuddered, like a man carrying a heavy pack that had shifted suddenly, and then the helicopter started spewing thick black smoke.

“Delta One-Six, I’m hit!”

“Fucker has an RPG!” shouted the other H-Boy pilot. He was moving his Jayhawk higher and orbiting counterclockwise to put his gun crews in position.

“Delta One-Six, she’s not responding.”

“Come on, Coleman,” said the other Jayhawk pilot. “Pull your PCLs off-line.”

“I’m losing it!”

Delta One-Six made two full rotations, wrapping itself in a black haze as it drifted toward a partially capsized super-freighter. As Barnes watched, the Jayhawk clipped the very top of the superstructure and hitched forward toward the ground in a dive. One of its gunners was holding onto his machine gun with one hand, the rest of him hanging out the door like a windsock in a stiff breeze. The pilot tried to level off the aircraft right before they hit, but only managed to snap the helicopter’s spine on impact.

A moment later, a thin plume of black smoke rose up from the wreck.

Then the radio exploded with activity. “He’s down, Echo Four-Three. Delta One-Six is down.”

“Get him some help over there. You got one moving!”

It was true. Barnes saw the pilot stumble out of the cockpit, his white helmet smoking. The man threw his helmet off and he fell into the water. When he bobbed back up to the surface he was holding a pistol in his hand.

“Oh, shit, Echo Four-Three, we got problems. I got infected moving into the area.”

“What direction?” asked Mama Bear.

“From the ten. I got a visual on thirteen of them.”

“Uh, Mama Bear,” said Faulks. “Ya’ll got a whole lot more than that. I got a visual on about forty or fifty over here at your two o’clock.”

“You want me to go down and extract your man?” Barnes asked.

“Negative, Quarter Four-One,” Mama Bear said. “Echo Three-Four, give me your status.”

“One second,” said the pilot. “We’re about to smoke out this RPG.”

A moment later, a steady stream of tracer rounds erupted from the Jayhawk’s gunners, slamming into the little pocket of debris beneath the tugboat’s pilothouse.

The shooting went on until the pilothouse collapsed.

“Echo Three-Four, RPG neutralized.”

“Your boy’s in deep shit over here, guys,” said Faulks.

Barnes rotated so he could see the downed pilot. The man was standing in the middle of a ring of zombies. The way he was standing, it was obvious he’d broken one of his legs, but the man fought bravely, placing his shots carefully, not rushing them.

“You guys gonna help him?” Faulks said.

“Roger that, Echo Three-four.”

The Jayhawk and the three other Dolphins moved into position, but Barnes could tell it was too late for the man on the ground even before the H-Boys started shooting. The man was pulled down below a sheet of corrugated tin by one of the zombies, and a moment later the water turned to blood where he had been standing.

“Echo Three-Four to Mama Bear, Delta One-Six has been compromised.”

A pause.

“Roger that, Echo Three-Four. Status report.”

Instinctively, Barnes swept the area, taking it all in. He saw the smoking helicopter, the zombies advancing through an endless plain of maritime debris, the uncles scrambling to escape the zombies, jumping into the channel and swimming for the boats. One of the boats had already made it a good fifty yards from the bank.

Echo Three-Four completed his status report. There was another pause while Mama Bear conferred with Papa Bear, and then Mama Bear gave the order that turned Barnes’s stomach.

“Smoke ’em all,” said Mama Bear. “Disable those boats and neutralize any targets in the water.”

A moment later, the air was alive with tracer rounds.

Barnes watched as the machine guns chewed up people and zombies and boats, and something inside him went numb.

Three miles to the east, on a small shrimp boat chugging quietly away from the darkened coastline, Robert Connelly heard the guns and saw the smoke columns rising up into the darkening sky.

“You okay, Bobby?” he said to his son.

The boy nodded into his shoulder and Robert hugged him.

Robert turned and looked over the faces of the forty refugees who had commandeered this boat with him. Several of them coughed. Half of them were sick with one kind of funk or another. Their faces were gray and gaunt, their eyes dull and languid in the darkness. They were all too tired, he realized, to understand just how lucky they were. The others had insisted on going to the main docks just above San Jacinto State Park, claiming there’d be more places to hide there. But Robert and his people had refused to go that route. They decided to take their chances, alone, down around Scott Bay. And now, as he listened to the explosions and the gunfire, it looked like that gamble was paying off.

He listened to the water lapping against the hull, to the steady droning thrum of the engines. He felt the wind buffeting his face.

He could feel the anxiety and the frustration and two years of living like an animal among the Houston ruins lifting from him. He took a deep breath, and though his chest hurt, it felt good to breathe air that didn’t taste like death and stale sweat and chemicals.

He squeezed Bobby again.

“I think we’re gonna make it,” he said.

“Bobby?”

A hard thud against the door.

“Bobby, let me see you. Bobby?”

Robert Connelly looked through a yellowed, grimy window, trying to catch a glimpse of his boy out there. He saw a few of the infected staggering around in the dark, trying to keep their balance as the boat pitched on the dark waves.

A hand crashed through the window and Robert stepped out of reach. The zombie groped for him, slicing its arm on the glass stuck in the frame. There was a time when seeing the zombie’s arm cut to ribbons like that would have made him vomit, all that blood. Now the arm was just something to avoid.

Robert got as close as he dared to the broken window. “Bobby, are you out there? Bobby?” Sometimes the infected remembered their names, responded to them. He had seen it happen before.

He waited.

There was another thud against the door, and this time something cracked.

“Bobby?”

He heard the infected moaning, the engines straining at three-quarters speed. The waves slapped against the hull.

He stepped over to the controls and looked out across the water. Far ahead, shimmering lights snaked across the horizon, sometimes visible, sometimes not, depending on the pitch of the bow over the waves. He thought for sure it was Florida. They had almost made it.

The thought took him back almost two years, to those lawless days after Hurricane Mardell. He remembered the rioting in the streets, the terrified confusion as nearly four million people scrambled to safety. Bloated, decaying corpses floated through the flooded streets. Starvation was rampant. Sanitation and medical services were nonexistent. Helicopters circled overhead for a few days after Mardell, picking up whomever they could, but there were so few helicopters, and so many to be rescued.

And then the infected rose up from the ruins.

At first, Robert believed they were bands of looters fighting with the authorities. He didn’t believe the reports of cannibalism. Paranoid hysteria, he called it. But then he saw the infected trying to get into the elementary school gym where he and Bobby and about a hundred others had been living. After that, he knew they were dealing with something more than looters.

He took Bobby on a desperate three-day trek north, and they made it as far as the quarantine walls, where they were turned back by soldiers and police standing behind barricades.

“We’re going to survive this,” he told his son. “I will keep you safe. I promise.”

He had said those words while they were sitting on the roof of a house less than half a mile from the wall, sharing a can of green beans they’d salvaged from the kitchen pantry. There was no silverware, none that they trusted the look of anyway, and they had to scoop out the food with their fingers. In the distance, they could see helicopter gunships sprinting over the walls. It was late evening, near dark, and they could hear the sporadic crackle of gunfire erupting all around them.

“It doesn’t matter, Dad.”

Robert Connelly looked at his son. The boy’s shoulders were drooped forward, the muscles in his face slack, like somebody had let the air out of him. “Bobby,” he said, “why would you say something like that? Of course it matters.”

There were two green beans floating in the bottom of the can. Robert offered them to Bobby.

The boy shook his head.

“There’s no point.”

“Bobby, please. It matters to me.”

The boy pointed at the wall. “Look at that, Dad. Look at those walls. Look at all those helicopters, all those soldiers. Think how fast they put all this up. They’re not ever going to let us go. They want us to die in here.”

Robert hardly knew what to say. Bobby was only thirteen years old, too young to think his life was valueless.

But he’d already noticed there were no gates in the quarantine wall.

He hoped they’d simply missed them.

They hadn’t.

For two years, Robert kept them alive, fighting the infected, rarely sleeping, scavenging for every meal. The struggle had carved a fierce resilience into his grain, a belief that his will alone was enough to sustain them against the cozy, narcotic warmth of nihilism.

With a small band of like-minded refugees, he found a serviceable boat in the flooded debris field of the Houston Ship Channel. There wasn’t a sailor among them, and yet they’d dodged the helicopters and slipped through the Coast Guard blockade undetected. For a glorious moment that first night, holding his boy, he’d believed they were really going to make it.

Now, he knew better.

One of the forty refugees on board the Sugar Jane was infected, and that first night, while they were at sea, he turned.

Robert Connelly was the only one left. He’d made a promise to his son and he’d almost kept it. He’d sought to escape the criminal injustice his government wrought upon him by locking him up inside the quarantine zone, and he’d almost succeeded.

But almost only counts in horseshoes and hand grenades, he thought, smiling faintly at the memory of one of his father’s favorite expressions. And now the Sugar Jane was a plague bomb bound for some unsuspecting shore.

But what was the sense in worrying about it? It didn’t matter anymore.

Not without the boy it didn’t.

Not to Robert Connelly.

There was another thud against the door and it splintered. A shard of plywood skidded across the deck, landing near his feet. Bloody fingers tore at the hole in the door. A face appeared at the widening crack, the cheeks and lips shredded to a pulp, the small, dark teeth broken and streaked with blood. The moaning became a fierce, stuttering growl.

That might be Bobby there; it was hard to tell. But it didn’t matter.

Robert looked over the controls. The boat would run itself. And it looked like they had enough fuel to finish the voyage. There was nothing left to do here. He stood as straight as the rolling deck of the boat allowed and prepared to run for it.

There was a hammer on the chair beside him.

He picked it up. Tested its heft.

It would do.

The door exploded open.

Bobby and two others stood there. Bobby’s right hand was nearly gone. So, too, were his ears and nose and most of his right cheek.

“Ah, Jesus, Bobby,” Robert said, grimacing at the wreckage of his son.

They stumbled forward.

Robert moved past Bobby and swung at the lead zombie, dropping it with a well-placed strike to the temple.

The other closed the gap too quickly, and Robert had to kick it in the gut to create distance. He raised the hammer and was rushing forward to plant it into the thing’s forehead when Bobby grabbed his shoulder and clamped down with a bite that made Robert howl in pain.

He knocked the boy to the deck and swung again at the second zombie. The claw end of the hammer caught the zombie in the top of the head and it dropped to the deck.

Bobby was on him again.

He grabbed the boy and turned him around and hugged him from behind, determined not to let go. A group of zombies was bottlenecking at the door. Robert knew he had only a few minutes of fight left in him. He charged the knot of zombies at the door and somehow managed to push them back. Hands and arms crowded his face, but he wasn’t worried about escaping their bites. Not at this point. All that mattered was getting on top of the cabin and up into the rigging.

Bobby struggled against his hold, but Robert managed to get his left arm across Bobby’s chest and over his right shoulder, pinning the boy’s arms. With an adult, it wouldn’t have been possible. But with a boy, and especially with a boy who had existed at a near-starvation level for two years, Robert managed fairly well.

The zombies clawed at him. They tore his cheeks and arms and neck with their fingernails. One of them took a bite out of his calf. But they couldn’t hold him.

He was breathing hard by the time he reached the top. He could feel his body growing weak. The infection felt like somebody was jamming a lit cigarette through his veins. But he reached the top of the rigging, and once he was there, he slipped a small length of rope from his back pocket and looped it around Bobby’s left hand, then around his own.

“It’s all right,” he whispered into Bobby’s ear. “Don’t you worry. We’re together now and nothing else matters.”

In the distance, he could see the bobbing string of lights that marked the Florida coast. Fireworks exploded above the horizon.

It was the Fourth of July.

“It’s beautiful, isn’t it?”

The zombie, his child, struggled against him. It wouldn’t be long now. He felt so weak, so sleepy. Soon, nothing else would matter.

They were together. And that was enough.

“That’s what counts,” he said. “I love you, Bobby.”

It was a cloudy, humid morning. Some of the prisoners were trying to sleep. Others were gazing vacantly out of the bus windows as it made its way southward through the heart of Sarasota, Florida’s coastal district. Billy Kline had his head against the wire mesh covering the windows, watching the others as they swayed in their seats to the motion of the bus. Beside him, Tommy Patmore was absently pulling at the loose threads of his work pants. The mood was subdued, quiet, each man lost to his own thoughts.

A few of the guys had their windows down, but not even the occasional draft of sea air that managed to find its way into the bus could cover up the smell. Their work clothes were little more than heavy-duty orange hospital scrubs with SARASOTA COUNTY JAIL stenciled across the back, and though they were supposedly washed after every use, they nonetheless stank of mildew and sweat and something less definable that Billy Kline had only now identified.

It was the rank odor of despair.

He’d been thinking a lot about despair lately. There were times when he felt it as a physically immediate and distinct sensation, like the burning itch between your toes after a few days of taking communal showers; or the painful swelling in your bowels that came with your first few meals; or rolling over at night and seeing the man in the cot next to you enveloped in a living haze of scabies. But there were other times when it was more tenuous, like when you heard the resignation in your mother’s voice when she said good-bye at the end of your ten-minute Tuesday-night phone call; or when you seethed with a cold, mute rage every time some bored guard emptied everything you owned onto his desk from a paper grocery sack and picked through it like he was looking for a pistachio kernel in a pile full of shells.

He felt so much rage.

Billy was twenty-five, halfway through an eight-month sentence for selling stolen property to undercover officers. Before that, he had done two months for car burglary, charges dismissed. And the year before that, he’d done three months, again for car burglary, and again with the charges ultimately dismissed. There had been other visits, too.

But this time was different.

This latest round of trouble had finally pissed his mom off to the point where she no longer asked for explanations or feigned credulity when he provided them unsolicited.

This time, he had finally hit bottom.

Beside him, Tommy Patmore sucked in a deep breath.

Billy leaned over and whispered, “You’re gonna unravel those pants you keep picking at ’em.”

A murmur.

“What’d you say?”

“Be quiet.”

Tommy glanced furtively around the bus. No one was paying any attention to them.

Billy followed Tommy’s gaze and frowned. “What’s wrong with you?”

One more look around.

“Ray Bob Walker came to see me this morning before we left. They asked me if I wanted to join.”

Billy sighed inwardly. He’d been dreading this.

“And? What’d you say?”

Tommy looked at him. It was enough.

“Ah, Tommy, you gotta be shitting me. What were you thinking?”

“Be quiet, Billy. They’ll hear you.”

“Fuck them. Tommy, I told you those Aryan Brotherhood assholes will get you killed. Is that what you want? You know what those guys do. What the fuck’s wrong with you?”

“Be quiet,” Tommy said. “They’ll hear you.”

He looked around the bus again. Billy looked, too. He saw a lot of bald heads: a mixture of blacks and Mexicans and white guys. The Mexicans and the white guys all had prison tats on their necks. The white guys came in two body types. You had the big guys, stout, meaty, biker types. They tended to be the older ones, doing time for robbery or check kiting. Then you had the lean ones, wiry, wild-eyed. They were the loud ones, the meth heads, the fighters, the ones with something to prove.

Tommy is going to fit in well with the younger ones, Billy thought. He had the body type. He had the same desperate air about him, an urgent need to fit in somewhere, anywhere. But then, all the young white guys who joined the Aryan Brotherhood started out that way. They were all angry, frustrated, a little frightened to find themselves alone in a world that demanded so much and yet seemed to promise so little in return. The Aryan Brotherhood offered safety. It offered direction. It offered a society that gave its members rank and made them something special within their own little world. It offered an “us” and a “them.” For someone like Tommy Patmore, the appeal was irresistible.

But they hadn’t looked twice at Billy. With a last name like Kline, they all assumed Billy was Jewish. But if he was, his family had neglected to tell him about it. And yet his name was enough to brand him a Jew in the eyes of his fellow prisoners. It made him a sort of nonentity, a prisoner like the rest, yet distinct enough that he didn’t fall inside any of the racial lines that sharply divide all U.S. jails and prisons. At six-one and a hundred and ninety pounds, he was big enough and tough enough to stand in the no-man’s land between the gangs, but it was a precarious existence. He was always watching the man behind him, because that man could turn on him at a moment’s notice, and maintaining that nearly constant state of vigilance wore Billy down, exhausted him.

That was the big reason why he hated to see Tommy Patmore get sucked into the gangs. He liked Tommy. Now, Tommy was one more individual he’d have to watch out for.

“Just do me a favor, would you?” Billy said. “Do your time smart. If they try to talk you into hurting somebody, get the hell out. The last thing you want to do is spend the rest of your life in a state pen someplace.”

Tommy swallowed the lump in his throat. Then he looked down at his hands folded in his lap.

That was all Billy needed to see.

“Ah, Tommy, you are one dumb son of a bitch. What did you agree to do?”

“Please don’t say anything.”

“What are you going to do? Tell me.”

Tommy looked around, then folded down the waistband of his pants, exposing a five-inch-long piece of tin that had been hammered into a crude shank, some duct tape wrapped around the blunt end as a handle.

“They haven’t told me who yet.”

“Ah, Tommy. For Christ’s sake.”

“Don’t say anything, Billy. Please.”

“I won’t,” Billy said.

He looked away in disgust.

In his mind, he tried to wash his hands of Tommy Patmore, though it wasn’t as easy as it should have been.

They were pulling into Centennial Park. The Gulf of Mexico stretched out before them like a flat green sheet of cold pea soup. Gulls circled over the water, filling the morning air with noise. The smell of the ocean was thick and pungent and pleasant. Billy closed his eyes and breathed in deeply. For a moment, he imagined that all his problems were somewhere else.

But it was the last quiet moment he would ever know.

The driver parked the bus in the middle of a nearly empty parking lot, and things started to happen quickly after that.

Billy shuffled off the bus with the others.

A few of the men stretched.

A guard came by and collected their SID sheets, the 3 x 5 index cards that contained all their personal information and that they had to present to the guards every time they moved from one place to the next.

Billy and three of the others were pulled off the line and brought over to the equipment stand.

A guard handed Billy a canvas sack with a strap meant to go over one shoulder and a sawed-off broom handle with a dull, bent spike shoved into one end.

“Collection detail,” the guard said. “You’re with Carnot. Over there.”

Deputy Carnot, who the prisoners called Deputy Carenot because he didn’t seem to give a shit about anything except talking on his cell phone, waved his men over and pointed them toward a large plain of grass south of the parking lot. He didn’t even have to stop talking on the phone. Billy and the other members of the collection detai. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...