- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

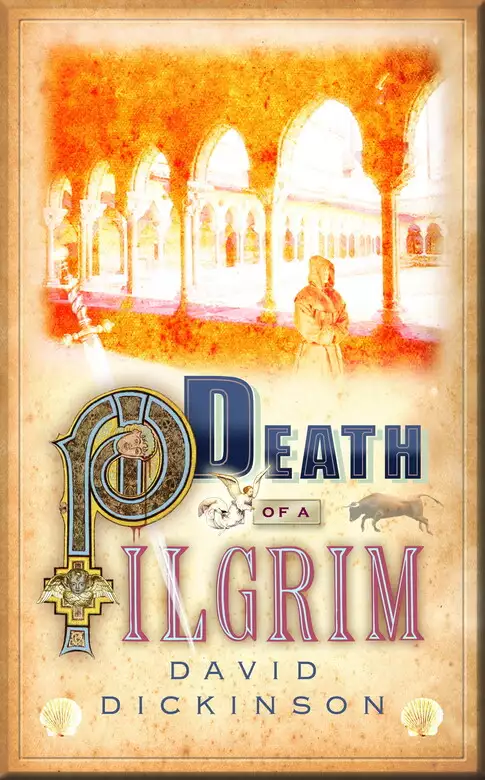

1905. A young man called James Delaney is dying in a New York hospital. The doctors and the nuns cannot save him. When his life is spared his tycoon father takes it as a miracle and organizes a family pilgrimage to the resting place of the boy's name saint, Saint James the Greater in Santiago de Compostela in Spain, the greatest pilgrimage site of the Middle Ages. The first modern-day pilgrim is killed in Le Puy en Velay in Southern France and Powerscourt is summoned to investigate. The pilgrims' progress across the holy sites is punctuated by further bizarre deaths. After his own life is put in terrible danger Powerscourt finally solves the murders on the day of the Bull Run at Pamplona in Southern Spain where young men race down the cobbled streets pursued by the bulls. The careless are gored to death, but it is up to Powerscourt to beware of the horns and other hidden dangers to finally resolve the Deaths of the Pilgrims.

Release date: September 1, 2011

Publisher: C & R Crime

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Death of a Pilgrim

David Dickinson

between heaven and hell. The work is divided into three horizontal sections. In the centre stands the largest figure of them all, Christ risen from the dead and wearing a long tunic with a scarf of

white wool embroidered with black crosses, usually reserved for the Pope and certain church dignitaries. Above him is a cross carried by two angels holding a nail and a spear. His right hand points

upwards and to his right. There a procession of the chosen ones, the Virgin Mary and St Peter, carrying the keys of the kingdom, lead the elect into paradise. On the strips of stone that divide the

panels there are Latin inscriptions. For Peter and Mary and Abraham, seated with the other victors in this religious race, the message is clear: ‘Thus are given to the chosen who have won,

the joys of heaven, glory, peace, rest and eternal light.’

On the other side of the work there is neither peace nor glory nor eternal light. Christ’s left hand points to the left and sharply downwards. Beneath him is a panel enclosed by two doors,

one ornate and graceful with two keyholes for the locks, the other with heavy metal supports and no keyholes. The chosen are led by the hand to heaven’s gate, but in front of the gateway to

hell diabolical monsters pummel the damned and force them into the vast open jaws of Leviathan: in the words of the Book of Isaiah, ‘Sheol, the land of the damned, gapes with straining throat

and has opened her measureless jaws: down go nobility and the mobs and the rabble rousers.’ Presiding over hell is Lucifer, Prince of Darkness, with a hideous grimace, bulging eyes and short

hair pleated to resemble a crown. To his left a miser or a thief has been hung up with a pouch of hoarded or stolen money wrapped round his neck, killed by the weight of his own greed. To his right

a messenger devil is whispering into Lucifer’s ear the news of the latest torments in his kingdom. Lucifer’s legs are adorned with serpents and his feet are pressing down to hold a

sinner being roasted on a brazier. In the panel above, an abbot is holding on to his crozier, prostrate in front of a deformed and bestial demon. In his net the demon has captured three other false

monks and is preparing further torture. Behind him, a heretic, his lips shut and a closed book in his hand, is having his mouth crushed while a demon devours his skull. To the right a false banker

or moneychanger is about to atone for his sins. A demon is melting the metal in a fire. He is tilting back the false banker or moneychanger’s head and preparing to make him swallow the liquid

of his infamy. A king has been stripped naked and a demon is preparing to pull him off his throne with his jaws. A glutton has been hung upside down with a pulley and forced to vomit his excesses

into a bowl while another fiend prepares to beat his feet with an axe. There is a couple taken in adultery and fornication, possibly a monk and a nun, now tied together for ever with a rope joining

their heads at the neck. The sins of pride and power are here in stone. A knight in an expensive mailcoat has been forced upside down by a demon pushing a pole into his back. Another seems to be

trying to tear his arms off. A scandalmonger, forced to sit in a fire, the flames licking round his waist, is having his tongue pulled out. A glutton with an enormous belly is going head first into

a piece of kitchen equipment, a cauldron or a boiling casserole. Love of money, love of power, love of women who are not your wife, love of gossip are all portrayed here, surrounded by demons with

fire and snakes and pulleys and axes and prongs to welcome you into hell. ‘The wicked’, the inscription proclaims, ‘suffer the torments of the damned, roasting in the middle of

flames and demons, perpetually groaning and trembling.’

These scenes are carved in the tympanum, the space above the doorway, in the Abbey Church of Conques in southern France. They were put in place early in the twelfth century, possibly around

1115. For a couple of hundred years they would have acted as inspiration and warning, threat and reward, to the tens of thousands of pilgrims passing through Conques on their journey to Santiago de

Compostela, the field of stars on the north-western coast of Spain, final resting place and shrine of St James the Apostle, which was the ultimate destination of one of Europe’s most

important pilgrimages. As they came into the great square in front of the church in Conques the pilgrims would have stared in awe, and possibly terror, at this visible representation of the likely

fate of all their souls in the world to come.

And now, in this year of Our Lord 1906, another group of pilgrims, bringing perhaps the same hopes and the same vices, are preparing to set out on the same pilgrims’ path to Santiago and

stand in front of the great tympanum at Conques. For them, as for their predecessors eight hundred years earlier, the inscription at the bottom of the sculpture still rings true: ‘Oh sinners,

if you do not mend your ways, know that you will suffer a dreadful fate.’

A bell was ringing, somewhere close. As the man struggled towards consciousness he thought he was deep, deep underwater. A ship was sinking slowly beneath him, heading straight

down for her last resting place on the sea bed. Maybe it was one of his ships. Ghostly figures, their clothes streaming behind them, were struggling towards the surface through the murky water.

Other figures, the fight abandoned, were falling backwards towards the ocean floor. Still the bell rang on. Now the picture in the man’s mind changed. He was in a coal mine. The bell meant

danger, a rock fall perhaps, or a collapsed shaft. Miners were running as hard as they could towards the way out, trying to escape before they were buried alive. Maybe it was one of his mines.

Then the bell stopped. The clanging was replaced by a loud knocking on the bedroom door. The man woke up and peered at his watch. It was a quarter to three in the morning.

‘Sir, sir, it’s the telephone, sir! It’s the hospital, sir!’ The butler’s voice was apologetic, as if he felt hospitals had no right to disturb his employer at this

time of night. He was still suspicious of telephones.

‘Of course it’s the bloody hospital, you fool,’ shouted the man, beginning to pull on the clothes he had dropped on the floor the night before. ‘Who else would telephone

at this time, for Christ’s sake? What did they say?’

‘You’re to come at once, sir. I’ve ordered the carriage.’

‘God in heaven!’ said the man. ‘I’ll be with you in a moment.’

This man didn’t answer telephones. He didn’t open letters. In normal times he didn’t tidy his clothes away. He didn’t clean his shoes. He paid other people to perform

these mundane tasks for him. They marked, these triumphs over the trivia of modern life, the milestones on his journey to unimaginable wealth, his town house in New York, his mansion in the

Hamptons, his yacht, his servants, the great industrial empire, the mountains of money sleeping in the vaults of the Wall Street banks.

As the carriage rattled through the empty streets of Manhattan, Michael O’Brian Delaney thought bitterly that he would happily give them all away in return for just one thing, the life of

his only son.

Michael Delaney was in his late fifties. He was slowly turning into a patriarch. He was over six feet tall and with a great barrel of a chest. Dark eyebrows hung over brown eyes that were liable

to flash with anger or excitement. His hair was brown, turning silver at the temples. He radiated a vast energy. One of his employees said that if you could somehow plug yourself into Delaney you

would light up like a candelabrum. Oil paintings of a more peaceful Delaney adorned the boardrooms of his corporations.

By the time his carriage drew up at the hospital entrance there was only one candle burning, to the left of his son’s bed. The little ward looked out on one side to the night streets of

Greenwich Village, on the other to the main ward for the terminally ill in St Vincent’s Hospital. Not that the nuns or the doctors ever referred to the ward in terms of terminal illness. It

was St James’s Ward to them. All the wards on this floor were named after one of the twelve apostles. Only in private did some of the less religious nurses refer to it as Death Row. As

Delaney tiptoed into the room on this November evening, nearest the main section an elderly nun, her entire working life spent in tending the sick and the dying on these wards, sat perched lightly

on a chair and stroked a young man’s hand, as if her caress could prolong his stay in these sad surroundings.

‘Thank you so much for coming, Mr Delaney. We felt we had to call you. We thought the end might be near, you see, but the crisis seems to have passed. He is no better, of course, but at

least he’s still with us.’

‘Thank God,’ said Michael Delaney, and sat down on the other side of the bed. These were familiar surroundings to him now, the dim lighting, the crisp white of the sheets, the

antiseptic pale green paint on the walls, the picture of a saint – Delaney didn’t know which one – on the wall above the bed, the faint smells of soap and disinfectant, the light

rumble of the trolleys outside taking away the dead on their last journey to the morgue, or bringing fresh consignments of the dying into the terminal ward. But he could not sit still for long. He

was restless, now leaning forward to peer into the young man’s face, now pacing on tiptoe over to the window and staring out into the snow swirling round the streets of his city.

This elder man was the father of the patient lying unconscious in the bed. Michael Delaney was one of the richest men in America. The patient was his only son, James Norton Delaney, and the

doctors were convinced he could not last more than a day or two. He was suffering from a rare form of what the doctors thought was leukaemia but knew little about. He was eighteen years old, James

Delaney, and this evening he was lying on his left side. He had been on the other side when the father sat on vigil until ten o’clock the evening before. Perhaps, the father thought, the nuns

had turned him over to make him more comfortable. James was a couple of inches shorter than his father’s six feet two. He had, as Michael Delaney recognized every time he looked at him, his

mother’s pretty nose and his mother’s mouth. Only in that high forehead, Michael Delaney thought, had he left his own print on the face of his only son. The young man’s forehead

was lined and wrinkled as if he had added thirty or forty years to his age. He was deathly pale. The light brown hair, almost straw in colour, straggled dankly across the pillow. His father had

lost count of the number of days his James had been in this isolation ward on his own now. Four? Five? Days and nights blended into one another; the vain hope that those light brown eyes might

open, that the lips in his mother’s pretty mouth might part and speak even a few words, was dashed as the ritual timetables of the nurses and doctors measured out their patients’ days.

Still there was no movement. Delaney leant down and kissed his son very lightly on the forehead. Every time he did this he wondered if it would be the last time his lips touched a living creature

rather than a corpse.

Shortly before seven o’clock in the morning the order changed in the Hospital of St Vincent. The elderly nun was replaced by a younger one. Delaney was conscious of

shadowy figures flitting silently to their places along the main ward. The Matron of the hospital materialized by his side and led him away.

‘You must have a change for a little while,’ she whispered. ‘Come with me.’

She led him through a series of passageways, the walls now pale blue and filled with paintings of the Stations of the Cross or scenes from the Gospels. Then she slipped away and he nearly lost

her. The Matron, Sister Dominic, was a considerable force in St Vincent’s. Almost all the male patients she met, even the very sick ones, were absolutely certain that she had chosen the wrong

profession. Think, they said to themselves, of those translucent pale blue eyes. Think of that face with its delicate features and that soft blonde hair. Think of that figure, alluring to some of

them even through the folds of the habits of her order. Quite what the right occupation for Sister Dominic might be they had no idea, but central to it, in the male view, was non-nunnery. No veils,

no wimples, no rosary beads, no strange garments, no prayers, let her be just another example of that great institution, American womanhood, available for courting, wonder, romance and, for the

lucky one, love and marriage. Often the male patients would dream about Sister Dominic, coming slowly back from drugged sleep after visions of nights spent in her company. Matron herself was well

aware of these strange currents of male interest, even male desire, that flowed invisibly around her person. She prayed regularly that God would punish her every time she thought about her

appearance. There was one quality, central to her personality, that most of the male patients did not see. Her faith was the most important facet of her life. And she had a deep, intense, very

personal calling to heal the sick. Sometimes she would tell herself that somebody in her care was just not going to be allowed to die. It would be too unfair. Sister Dominic never told any of her

colleagues about these missions of salvation. When all her efforts failed she would repair to her bare cell and weep bitterly until she was next on duty, sometimes refusing to eat or sleep for days

at a time. Failure did not come easy to the Matron of St Vincent’s Hospital.

‘Where are we going?’ Delaney whispered.

‘We are going to the chapel,’ she replied.

‘We are going to pray.’

The man stopped suddenly. He told her he had forgotten how to pray. Bitterly he remembered the times he had ignored all forms of religious instruction as a boy

and had played truant, the church services where he had deliberately ignored the words and the responses, the Sunday mornings he had managed to flee from the Church of the Blessed Virgin and gone

to hang around the waterfront, the beatings from his father for not taking his faith seriously. He remembered too his father shouting at him that one day he would be sorry he had not paid attention

to the priests. One day the sins of his past would come back to haunt him. Well, Judgement Day had finally arrived, here in this place where the sheets were changed twice a day and crucifixes and

rosary beads were as common as top hats on Fifth Avenue.

Matron told Delaney he should not worry about the praying on this occasion. She would find him something else to do. She asked him to wait for a moment outside the main entrance to the chapel.

When she came back there was a ghost of a smile about her face. She led him into the little church, for so many of the nuns the very heart of the hospital. There were enough pews to hold about

forty people. All of them were filled, mostly with kneeling women. All of these Sisters, she told him, had come to pray for his son James. It was a special effort for a special young man. When

Delaney asked her what he had to do, she gave him a box of matches. She pointed to the great banks of candles inside all the side chapels and below the paintings on the walls.

‘You must light these,’ she said, ‘and as you light each one, you must pray to God in his mercy to save the life of your son. Do not worry if we have gone before you have

finished. You must light them all and then return to the bedside. Later on this morning I am going to find you a priest or a chaplain to teach you how to pray.’

With that Matron knelt to the ground in the pew beside him. Delaney turned to the candles to his left and began lighting them very slowly. Please God, spare the life of my son James, he said to

himself, feeling coarse and awkward as he did so. Gradually, as he repeated his prayer, he began to weep. The tears poured down his face and would not stop. Sometimes they would drop on to his

match and extinguish the possibility of lighting another symbolic message before it had even begun. The nuns took little sideways glances at the weeping tycoon but left him to his ordeal. At eight

o’clock the Sisters began to peel away, walking quietly back to their nunnery or their places on the wards. Matron sent word to a Father Kennedy, asking him to come to the hospital and to

James Delaney’s ward later that day. Michael Delaney had not finished yet, though one wall was a blaze of light, dancing off the faces of the saints or the waters of the Lake of Galilee. It

was so strange for Delaney, asking an unknown and invisible God to save the life of his only son. His was not a world made up of these religious or metaphysical certainties. His was a world of

balance sheets, of strike-breaking, of amalgamations, of mighty trusts, of personal enrichment, of power, power over the lives of the thousands of people who worked for him, power over the local

politicians who might need a subvention to help them through their next election, power over grander politicians, aspirant statesmen perhaps, whose need for invisible assistance was often as great

as their hunger for high office. Alone in the chapel with his matches and his candles he thought of Mary, the boy’s mother, who had died three years before. She too had come to this last

resting place of Manhattan’s Catholics and been tended by the nuns until she died. There had been, he shuddered slightly, a great deal of pain. It was a mercy, they said, when she was called

home. Delaney didn’t think it had been a mercy then and he didn’t think it was a mercy now. This God person, he reckoned, reaching up to the top of a sconce almost out of reach, He had

a lot to answer for. If He took James as well, Delaney thought, he would write God out of his account books, sell Him off to a competitor, even at a knockdown price, put Him out of business, close

this God outfit down once and for all.

Just before nine o’clock all the candles were lit. Delaney sat down in one of the pews and looked around him. He tried to remember the words but they had gone. Hail Mary, that meant

something, he was fairly sure of it. The same went for Our Father. But of what those nuns said as their knees rested on the stone floor he had no idea. He turned back at the door and looked one

last time at the candles. He wondered if their light would go out before his son’s life. Suddenly his brain took off into a strange mixture of his own world and the very different world of

the hospital. Did they have enough candles here at the hospital? Did the other hospitals? This was something he, Michael Delaney, could do. His mind set off on a journey round the economics of

candle production, possible advanced production techniques that could reduce the cost of manufacture and the numbers of employees, candle transportation routes and freight rates, distribution of

candles round the churches and hospitals of New York. Would it be cheaper to amalgamate candle supply into general delivery lines of food, linen and so on, or simply have one outfit responsible for

distribution? What about the competition in candle land? Could he buy them out? Could he drive them out of business?

As Delaney pondered these questions on his way back to the ward a whistle blew less than a mile away at one of New York’s great railway stations. A mighty passenger train moved slowly out

on its way to Chicago. The train was nearly full and promised to be a busy one for the stewards and the cabin staff. This railway line was one of many owned by Delaney’s companies. This

section of his three and a half thousand railway employees across the eastern seaboard of the United States was clocking on for work on the normal ten-hour shift with no breaks, which would see

them travel halfway across a continent. And, in the rear part of the train, there was a steward who rejoiced in the name of Patrick or Paddy Delaney, a cousin of the proprietor on the Irish side of

the family though the two had never met.

The boy had hardly moved in his bed when his father returned. The new Sister on his left was also stroking his hand. Delaney paced up and down the room, staring into the face of his son, doing

more planning for his schemes for a candle monopoly, then peering out of the window. Sometimes he cried and wished he knew the words of the prayers. Ten o’clock, then eleven o’clock

passed, and by noon Delaney’s train with his cousin on board was well into upstate New York. Occasionally a doctor would come in and look at the young man, feeling his pulse and taking his

temperature by the heat on his forehead. None of the doctors had seen a version of the disease like this. They were acutely conscious that any new treatment might not cure the young man. It might

kill him instead.

Shortly before one o’clock a priest appeared and took Michael Delaney aside. You must go home and rest now, the priest told him. You do not need to rest for a very long time, but you must

maintain your strength for what might happen. I, Father Kennedy, will meet you here in the chapel at seven o’clock this evening. The nuns will have finished their services by then. Please, I

will stay with the boy a while.

Delaney’s carriage and Delaney’s coachman had waited for him outside St Vincent’s. The coachman spent his time playing cards with the porters or reading one of his ever-growing

collection of magazines about motor cars. Mercedes Benz. Ford. Chrysler. Cadillac. Bugatti. The coachman was very fond of his horses but these names took him to another world where he sat proudly

at the wheel of a mighty machine and drove his master up and down the eastern seaboard, hooting his horn at recalcitrant pedestrians, a muffler round his throat and a chauffeur’s cap upon his

head. As they made their way slowly through the crowded streets they were overtaken by a couple of fire trucks, their insistent bells shrieking and echoing round the thoroughfares. Sitting inside

his carriage, Michael Delaney remembered that other bell which had woken him up earlier. He thought suddenly of the numerous funerals he attended as his contemporaries in the Wall Street jungle

died off in their prime. Delaney never missed one of these sad occasions, come, his enemies whispered, to make sure that another of his competitors had really been removed from the earthly market

place. He recalled the words in one of the addresses, usually full of sentimental rubbish about the dead man, now transformed from a rapacious capitalist into a virtual saint and generous

benefactor of the poor: ‘Ask not for whom the bell tolls, it tolls for thee.’ Were these bells ringing for him? For his son? Michael Delaney huddled into his greatcoat and tried to

pray.

The Archbishop of New York used to say that the net wealth of Father Patrick Kennedy’s flock was about the same as that of a medium-sized country like Sweden or

Portugal. Delaney was a parishioner of his, a very occasional worshipper at Mass, like so many of his kind, but a generous contributor to church charities, like so many of his kind. Quite simply,

Father Kennedy was the parish priest in the richest part of the richest city in one of the richest countries on earth. He was popular with his congregation, Father Kennedy, with his charming voice

and elegant manners from the Old Confederate State of Virginia. In his youth Father Kennedy had been slim, ascetic almost, a devoted reader of the works of Meister Eckhardt and St Thomas Aquinas.

He was about five feet ten inches tall with a Roman nose and his blue eyes were then fixed on another world. The temptations of the flesh did not reach him in his rich parish, but the temptations

of the table made an impact. Middle-aged now, he was known to his critics as the Friar Tuck of Manhattan. He glided through the Fifth Avenue drawing rooms with his polite smiles and his anecdotes

from his time in Europe a decade before. Father Kennedy was very successful at drawing new converts into the bosom of Mother Church, and as most of his recruits were as rich as everybody else in

the parish, St James the Greater increased yet further in wealth until cynics in poorer parishes referred to it as St James the Richer.

Father Kennedy worried a great deal about the very rich. He saw all too clearly that the leisure of those who lived off the interest on their money, or even, in some cases, the interest on the

interest, without needing to work at all, could be corrosive. Souls could be lost in the fripperies of the season as easily as they could in the brothels and the gambling dens of the Bronx. He

worried a great deal, Father Kennedy, about camels and their ability to pass into the kingdom of heaven. Three times he had asked to be transferred to a parish in one of the slums of New York.

Three times the church authorities had refused. The Archbishop always maintained that remaining in Manhattan would be good for Father Kennedy’s soul. The truth was somewhat different. Father

Kennedy was the greatest benefactor of the poor in the whole of New York. Not personally, but through his parishioners, who would contribute funds for the education or housing of the poor, for the

support of the destitute, for building new churches where none had been before. It was all so easy. The rich just reached for their chequebooks as they might hold out their hands for a glass of

champagne at a Fifth Avenue soirée. After watching this waterfall of charity dollars for years Father Kennedy himself had become cynical. They’re trying to buy their way in with false

currency, he thought. God doesn’t want their money, he wants their souls. So, while he never stopped the cascade of charity, he was beginning to think about deeds rather than dollars as the

way to improve the spiritual health of his flock.

Michael Delaney’s staff pressed anxiously around him as he returned to his mansion. None dared to ask the question they most wanted to – how was James? Was he

still alive? The young man’s father refused all offers of refreshments except for a large glass of bourbon and took himself off to bed. He slept badly. He dreamt he was in a cemetery looking

at his wife’s grave, the two marble angels he had had erected a year after her burial towering above the marble tomb. But now, by her left side was another tomb, to his son, passed away in

the month of November 1905. This month. Then he noticed what was happening by her right-hand side. Four gravediggers were excavating a third burial place for another Delaney. It could only be

himself, last of the line. There was no inscription yet on his grave, he realized. He might have years to go still. With that comforting thought he woke up to a darkened city at a quarter to six in

the evening.

He was early at the chapel in St Vincent’s Hospital. Somebody had removed the guttered candles and replaced them with fresh ones. Delaney began to light them, remembering to say the words

the Matron had told him earlier that day. Father Kennedy came and sat down with Delaney in the very first row, a large silver cross in front of them. Just repeat the words after me, he said to

Delaney, that’s all you need to do for now. They started with Hail Mary.

Two doctors, one middle-aged and one very young, were examining James Delaney. The nurse had moved unobtrusively to the back of the room. They agreed that he looked a little better, that the

terrible chalky colour of the previous day was less pronounced.

Father Kennedy and Michael Delaney had moved on to the Lord’s Prayer. Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive them who trespass against us . . .

And so a strange ritual evolved. Early in the mornings Delaney would pray with Father Kennedy in the chapel and relight the candles while the doctors looked at his son. He would wait by the

bedside during the day and early evening, departing occasionally to care for his business or buy out a competitor. One of the nuns would sit on the other side of the young man and stroke his hand.

Delaney now had reading matter, a missal provided for him by Father Kennedy. He also had a special prayer of his own. It was, he knew, somewhat unorthodox, owing more to contemporary business

practice than to the Gospels. If God would save his son, he would, in return, make a mighty offering to God. The nature of the offering was to be determined by Father Kennedy, who smiled

delphically when told about the Delaney Compact. Early in the evening all the nuns and Matron would pray for James for half an hour. His father would light the candles and say some of the new

prayers he had been taught by Father Kennedy. As the priest watched the intensity of Delaney’s concern, the depth of his grief, he wondered if there might be other grounds for sorrow and

remorse in his past, now mingling with anxiety for his son James.

As Delaney became a part of this medical world, so different from his own, he found his eyes roaming the wards and the corridors for a sight of Sister Dominic. Even in her formal Matron’s

clothes, he

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...