- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

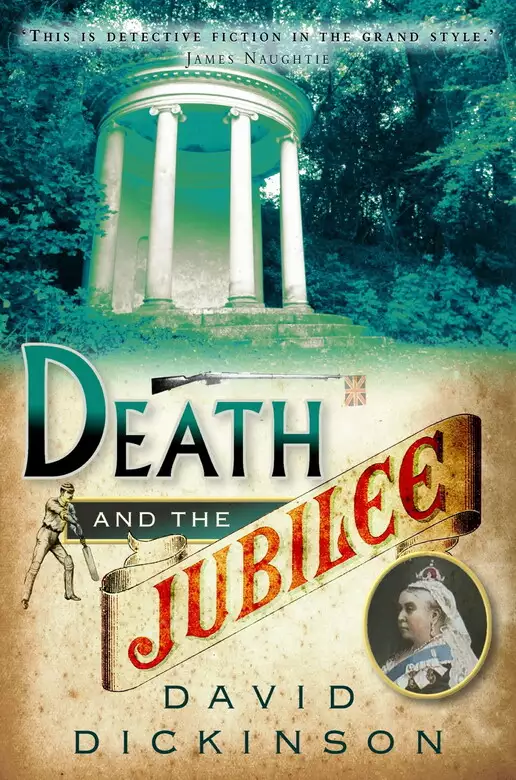

Find a murderer - and save the Queen's Jubilee! It is 1897 and the London is preparing for Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee. But a corpse is with no head or hands is dragged out of the Thames. The dead man was old and proserously dressed, but there are no other clues to his identity and the police ask for the discreet assistance of Lord Francis Powerscourt. His investigation leads him to a mysterious mansion in Oxfordshire, with classical temples in the gardens and in the house, a second corpse killed in a fire. On the track of the murderer, Powerscourt realizes that both he and his family are in mortal danger - and the outcome could wreck the Queen's Diamond Jubilee...

Release date: September 1, 2011

Publisher: C & R Crime

Print pages: 288

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Death and the Jubilee

David Dickinson

One nondescript room at the top of the War Office in London had become the nerve centre of the British Empire. It had two small windows that looked out over the rooftops of the

capital, a threadbare carpet, a fading portrait of Queen Victoria over a mean fireplace, a battered desk and an ink-stained table.

But these cramped quarters were the focal point for one of the greatest movements of military personnel the world had ever seen. Tens of thousands of soldiers and cavalrymen were to sail across

the globe on orders despatched from this bureaucratic command post.

This was the Planning Headquarters for the Jubilee Parade in honour of Victoria the Queen Empress on her Diamond Jubilee on 22nd June 1897, now a year and a quarter away. This was to be the

grandest parade the world had ever seen, grander even than Roman triumphs through the eternal city two thousand years before. No captured chieftains or Oriental despots in chains were needed to

adorn this procession. These were Victoria’s subjects, to be carried across the red-coloured map that marked the glory of her Empire. Hussars from Canada and carabiniers from Natal had to be

transported, Hong Kong Chinese Police, Cypriot Zaptiehs, Dyak head-hunters from North Borneo, Malays and Hausas, Sinhalese and Maoris, Indian lancers and Cape Mounted Rifles, cavalrymen from New

South Wales and Jamaicans resplendent in white gaiters. Fifty thousand troops were to march through London to a Service of Thanksgiving at St Paul’s, a splash, an explosion of colour on the

dull grey buildings of the capital, a heady and intoxicating draught of romance for the million citizens expected to wonder at their passing.

General Hugo Arbuthnot was the man in charge of this huge enterprise. He had been a soldier all his life, a life spent in the mundane details of military planning and administration. Not for him

the glory of the cavalry charge or the heroic defences of the British Army in adversity. His campaigns were fought not with the sword but with pen and ink, fought on paper in committee meetings and

the interminable boredom of staff work. From this unpromising terrain he had created an empire all his own. If some dashing general was faced with a complicated logistic problem he felt was beneath

his talents, Arbuthnot was the man. If the Army wanted a vast feat of organizational complexity, Arbuthnot was the man. Above all, he was known as having a safe pair of hands.

But there was one cross he had to bear, as he repeatedly told his wife in their tidy house in Hampshire, the lawn always neatly trimmed, the roses punctually pruned, on his return from the daily

grappling with shipping lines and the near insoluble problem of camel feed on requisitioned steamers. General Arbuthnot was also in charge of security on Jubilee Day. Security, he used to say, was

not something, like cases of rifles or ammunition, that could be nailed down. It was slippery. It was elusive. And some of the people he had to deal with on the issue of security were, he felt,

decidedly slippery, decidedly elusive.

This morning Arbuthnot had convened a meeting in his office of some of the key elements in the Whitehall jungle whose views had to be consulted. On his left sat the Honourable St John Flaherty

of the Foreign Office, an exquisitely dressed young man whose diplomatic reticence was marred by a fabulous gold watch. Flaherty was renowned in diplomatic circles for the quality of his prose and

the regularity of his affairs with diplomatic wives. On Arbuthnot’s right sat a harassed-looking Assistant Commissioner from the Metropolitan Police. Furthest away was Dominic Knox of the

Irish Office, a short and wiry man with a small beard and a secret passion for the gaming tables. Knox had no official job title but wandered through the bureaucratic maze as a senior member of the

Secretariat in Dublin Castle. Everyone round General Arbuthnot’s table knew that this was the foremost expert in Britain on terrorism, subversion and intelligence gathering in Ireland.

‘Perhaps, Mr Flaherty, you could enlighten us with the views of the Foreign Office?’ General Arbuthnot had little time for the Foreign Office, a talking shop full of milksops in his

view.

‘Thank you, General, thank you.’ Flaherty smiled a condescending smile. ‘I could burden you with the reports we have collected from our embassies round the world,

gentlemen.’ Flaherty waved at a pile of cables in his folder as if it were a bad hand at whist. ‘But I won’t. The key fact is this, gentlemen. Assassinations since the time of

Julius Caesar and before have always been home-grown affairs. Brutus and Cassius stabbed their fellow Roman on the Ides of March. Roman assassinates Roman. John Wilkes Booth shot his President

Abraham Lincoln at the theatre in Washington. American assassinates American. Russians blew up their Tsar Alexander as he drove through St Petersburg in his carriage fifteen years ago. Russian

assassinates Russian. In some parts of the Balkans and the Middle East, I believe, more rulers are assassinated than actually die in their beds.

‘In short, the most likely person to try to assassinate Queen Victoria or let off a bomb is an inhabitant of these islands, a Briton trying to assassinate a Briton. Madmen and fanatics

from anywhere in the world cannot be ruled out of course, but you cannot legislate for the insane.’

‘Quite so,’ said the General, looking up from the notes he had just made. ‘Let me now turn to the position of the Metropolitan Police. Mr Taylor.’

William Taylor, Assistant Commissioner, felt slightly out of place. He brushed his remaining hairs back across his forehead. He was a practical policeman. He had risen through the ranks from

mundane police stations in Clerkenwell and Southwark, Hoxton and Hammersmith. It would be his task to issue the public order notices, to prepare the plans of his force for the maintenance of order

on the day of the procession. The historical sweep of the Foreign Office world view left him cold.

‘Our position, General, is quite simple. We have increased our penetration of the various subversive societies that operate in and around the capital. You will recall that we were allotted

extra monies for the purpose. We are still working on our security strategy for the week or so surrounding the Jubilee. At one point we considered banning the public from the roofs of all the high

buildings along the route of the parade to St Paul’s Cathedral, but the Home Office believe it would be politically impossible.’

William Taylor winced slightly as he remembered the response of the Home Office Minister. ‘Completely, totally and utterly impossible! Impossible! We are meant to be celebrating the glory

and power of the British Empire! Are we so frightened that we have to have a flat-footed constable on every rooftop looking for assassins? What would they do if they saw one? Blow their

whistles?’

‘For the time being, General,’ Taylor went on, ‘we watch and wait. We are in very close touch with our colleagues from the Irish Office, as you know.’

A telephone was ringing insistently in the room next door. Noises of the great world beyond the windows infiltrated the War Office, clocks tolling, the rumble of traffic, the shouts of the

delivery men. General Arbuthnot looked briefly at his favourite picture. It showed an enormous military parade at Aldershot, ranks of troops stretching without end towards a pale blue horizon. Not

a button, not a plume was out of place. That was as it should be. General Arbuthnot had organized the parade.

‘Knox,’ the General said suddenly, ‘you may be the last person to speak, but I am sure we all believe that your intelligence may be the most serious.’

‘Thank you, General.’ Dominic Knox knew that the General did not care for him. He did not care for the General. Knox looked as if he might have been a priest or a philosophy don.

Years of reading through the ambiguities of intelligence reports, of second or third or even fourth guessing the words and actions of his opponents had left him with severe doubts about the

accuracy of language, written or spoken.

‘I am sorry to have to disappoint you, gentlemen. The only honest answer I can bring to this meeting about the level of threat from Ireland on Jubilee Day is that we do not know. We do not

know what new groups may have formed over there by next year. Undoubtedly there is a small section of Irish opinion which would dearly like to assassinate Queen Victoria.’

The Army, the Foreign Office and the Metropolitan Police looked shocked as if Knox had just blasphemed at Holy Communion in Westminster Abbey.

‘We have our intelligence systems in place. We should hear of any such plan inside forty-eight hours. But the Irish are very cunning. They may have made their plans some years ago. They

may have planted the would-be assassin in a safe job in London already. He may be going about his lawful business even as we sit here this morning, a waiter in a club or a servant in a grand house

somewhere along the route perhaps, watching and waiting for the parade itself when he will reveal himself in his true colours. It may be that we have to investigate all those who have come to

London in the last two years.

‘I am sorry that I cannot bring more hopeful news. But I would be betraying my duty if I did not tell you how we see the position. There is over a year to go before Her Majesty sets out

from Buckingham Palace en route to St Paul’s. We shall be watching the threat from Ireland on an hourly basis until then. Hour by hour, if not minute by minute.’

Berlin 1896

‘Only in war can a nation become a true nation. Only common great deeds for the Idea of a Fatherland will hold a nation together. Social selfishness, the wishes of

individuals, all must yield. The individual must forget himself and become part of the totality; he must realize how insignificant his life is compared with the whole. The State is not an Academy

of Art, or of Commerce. It is Power!’

Five hundred pairs of eyes were riveted on an old man at a lectern. Once more the audience in the Auditorium Maximum of the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin rose to their feet. They

cheered, they stamped their boots, they waved their hats in the air. Heinrich von Treitschke, the Professor of History, was old now. People said he was dying. His delivery was not couched in the

musical cadences of some of the other professors whose eloquence could never pack the lecture halls like he could; it was harsh, and as his deafness increased he shouted in a rough monotone like a

man trying to speak in a storm.

‘If a State realizes that it can, by way of its power and moral strength, lay claim to more than it possesses, it turns to the only means of achieving this, namely the force of arms. It is

absurd to regard the conquest of another province or another country as theft or as a crime. It is sufficient to ask how the vanquished nation may best be absorbed in the superior

culture.’

Von Treitschke had been giving these lectures on German politics and history for over twenty years. His audience was composed not merely of university students, but of bankers, businessmen,

journalists, army cadets from the garrisons of Berlin and Potsdam. For many of them, who attended week after week and year after year, the message of the ancient historian, his hair white, his face

lined, his expression fierce as he preached the love of the Fatherland, had become more important than that of any preacher they might hear in the churches of the capital. The body and blood of

Christ had been replaced with the bodies and the blood of Germany. Here was a true Prussian prophet in his final years leading his people out of the wilderness into the promised Fatherland.

‘When we look . . .’ the old man paused and stared defiantly at the lecture hall and his disciples, ‘when we look at the lessons of our great past towards our glorious future,

what do we find? We find that Germany’s greatest enemy lies not to the east in Mother Russia, but in the west! Yes, in the west! Our greatest enemy is an island! An island whose arrogance and

presumption has too long denied our great Fatherland its place in the sun, its historical role at the heart of world power.’

Standing by the entrance was a tall thin young man called Manfred von Munster whose face had all the ardour and faith of the congregation. But his eyes were fixed on an even younger man who sat

in the second row and whose eyes were burning with passion. He took notes in a small black book and he was first to stamp his feet, to roar on the devotion of the faithful. Von Munster had attended

every one of Treitschke’s lectures for the past ten years. For him they were not just a confirmation of his creed, a communion with other believers. They were a recruiting ground.

‘They have a song, these English,’ the Professor was shouting now as he built towards his peroration. ‘They call it “Rule Britannia, Britannia rule the waves.” That

has gone on for too long. England, with its decadent and effete aristocracy, its complacent and avaricious merchants who have used the Royal Navy to build up their trade and commerce across the

globe, its slovenly and unhealthy workers, this England has been allowed to rule for far too long. One day, my fellow countrymen, when we have built our strength on sea as well as land, one day it

will be Germany’s destiny to replace these sordid shopkeepers in the ranks of the world powers. No more Rule Britannia!’

The audience were on their feet, throwing notebooks, hats, pens, hands into the air. ‘Treitschke! Treitschke!’ they shouted as though it were a battle cry. ‘Treitschke!

Treitschke!’

The old man held up his hand to quell the noise. He looked, thought Munster, like Moses on the mountain top, about to descend with the tablets of stone to his unworthy people.

‘My friends! My friends! Forgive me! I have not yet finished my lecture.’

In an instant the audience went quiet. They did not sit down, but remained on their feet to hear the last words of the master.

‘No more Rule Britannia . . .’ Treitschke paused. Silence had fallen over his students as though a cloud had blocked out the sun. He stared at his audience, scanning their faces row

by row. ‘Rule Germania! Rule Germania!’

The cheers rolled out round the auditorium. Professor von Treitschke departed the stage slowly, leaning on a stick, declining all offers of assistance. The strength seemed to flow out of him now

his lecture was over. He looked like any other old man, close to death perhaps, walking back alone to his apartment after the day’s chores were done.

But for von Munster the day’s work was only just beginning. He struck up a conversation with the young man in the second row as they struggled through the crowd leaving the university into

a freezing Berlin.

‘Forgive me, please. Haven’t I seen you at the lectures before?’

‘You have.’ The young man’s face glowed with pride. ‘I have attended every single lecture this term. Isn’t it a pity that they are nearly over?’

Von Munster laughed. He knew the young man had attended every lecture. He had watched him every time, looking not at Treitschke’s face but at his companion and his growing devotion to the

cause of a greater Germany. This was part of his job. Now, von Munster felt sure, he could bring another disciple into the fold.

‘Have you time for a quick cup of coffee? It seems colder than usual today.’ Munster spoke in his friendliest voice.

‘If it is quick,’ the young man said. ‘I have to get back.’

‘I was wondering,’ von Munster began as they sat in the back of the coffee house, ‘if you would like to be more closely associated with the Professor and his ideas. But,

forgive me, how very rude, I don’t even know your name!’

‘My name is Karl,’ the young man smiled, ‘Karl Schmidt. I come from Hamburg. But tell me more about the Professor and his ideas. Are there more lectures I could go to? Or is it

true that von Treitschke is dying?’

‘I believe he may be nearing the end, but his message will live on,’ replied Munster, lighting a small cigar. He looked carefully round the café, making sure that in their

little alcove by the fire, they were truly alone. Pictures of German soldiers lined the walls. ‘It’s not a question of more lectures, alas. Would there were more where we could be

inspired by the passion of the master. No.’ He leaned forward suddenly, stirring his coffee very slowly as he spoke. ‘There is a society devoted to his ideals.’ He looked Karl

Schmidt directly in the eye. ‘It is a secret society.’

‘Oh,’ said Schmidt, feeling alarmed suddenly. His mother had warned him about the secret societies in the universities and the army regiments, terrible places, she had said, devoted

to duelling and strange rituals like Black Masses and the worship of the dead. She had made Karl promise that he would never, never, have anything to do with these dens of vice. ‘What kind of

secret society?’ he asked, his pale blue eyes troubled in the cigar smoke.

‘Oh, it’s not what you might think!’ Munster laughed. ‘We don’t go in for drinking our blood mixed with wine, or ceremonies with black candles or anything of that

sort.’ He leaned back in his chair, as though he were insulted by the younger man’s hesitation. ‘It’s much more serious than that.’

He paused. Long experience had taught him to make the secret society seem as important as possible.

‘How do you mean?’ The young man was leaning forward in his chair now.

‘Well, we believe that von Treitschke’s message is far too important to be sullied with the pranks and the games university students and army cadets play, far too

important.’

He paused to see if his message was getting through. It was.

‘But how do you join? What is the purpose of the society? What is it called?’ Karl Schmidt sounded as though he would sign on the spot.

‘I will tell you the name of the society in a moment. Its recruits have to satisfy four senior members that they will do everything to follow von Treitschke’s teaching and to advance

the cause of Germany. Not just in their relations with their friends and family. It isn’t like joining a religious group or a church. It’s much more important than that. It may be that

their place in life gives them special opportunities to further the cause. Every new member has to swear an oath to do that. Then we sing our hymn, our Te Deum, our Ave Maria. Can you guess what it

is?’

The young man shook his head.

‘I’m sure you would get it if you had time to think. It is “The Song of the Black Eagle” which von Treitschke himself composed after France declared war on Prussia in

1870.’ Munster began to hum softly.

‘Come sons of Germany,

Show your martial might . . .’

Karl Schmidt joined in, smiling with pride.

‘Forward to the battlefleld,

Forward to Glory.

At the sign of the Black Eagle

Germany shall rise again.’

‘Hush,’ said Munster, ‘we mustn’t get carried away, even with the Treitschke song. The society is called the Black Eagle. Every new member receives a ring like this one

so he can recognize other members if necessary.’

He pulled a silver ring off his finger. It had no inscription on it. Karl Schmidt looked puzzled.

‘Look on the inside. If you look carefully you will see a very small black eagle, just waiting on the inside, waiting to fly away in the cause of a greater Germany.’

The young man sighed. Munster waited. It was for Schmidt to make the next move. ‘I think – no, I am sure,’ he said, ‘that I would like to join. But I am not sure how I

can be of service.’

‘You never know who may or may not be able to serve,’ said Munster severely. ‘That is for the senior members to decide. Sometimes people may have to wait for years before they

find themselves in a position to do their duty. But tell me, what is your profession? Are you a student here at the university?’

‘I wish I was,’ said Karl sadly. ‘I’m a clerk at the Potsdamer Bank just round the corner.’

‘You work in a bank? You know how the banking business works?’ Von Munster sounded eager, very eager.

‘I don’t know all of it yet,’ said Karl Schmidt apologetically, ‘but I am learning. And my English is quite good now. The bank pays for me to go to evening

classes.’

‘My friend, my friend,’ Munster was smiling now and seized the young man’s hand, ‘tonight or tomorrow we shall introduce you into the society. We shall all sing

“The Song of the Black Eagle” together. Singing it together, the new recruit and the senior members, that is very important. And then, in a little while, it may be that we have some

very important work for you. Work of which von Treitschke himself would be proud!’

‘Work here in Berlin? Inside the Potsdamer Bank?’ Karl looked puzzled again.

‘No, not in Berlin’ said Munster. He sounded very serious indeed. ‘In London.’

They came across London Bridge like an army on the march, regiments of men and a few platoons of women, swept forward by the press behind them. They were a sullen army, an army

going to a siege perhaps, or a battle they didn’t think they could win. Behind them the roar of the steam engines and the shrieking of whistles heralded the arrival of reinforcements as train

after train deposited its carriages into the station.

To the left and right of the army was the river, two hundred and fifty yards wide at this point, full of ships from every corner of the world. Shouts of the lightermen and the sailors added to

the noise. Ahead lay their destination, the City of London, which swallowed up nearly three hundred thousand people every day in its eternal quest for business. Junior clerks with shiny black coats

and frayed collars dreamed of better days to come. Stockbrokers with perfectly fitting frock-coats hoped for fresh commissions and extravagant customers. Merchants in all the strange substances the

City dealt in, cork and vanilla, lead spelter and tallow, linseed oil and bristles, prayed that prices would get firmer.

All this silent army were coming to worship at the twin gods of the City, Money and the Market. Money was cold. Money was the yellow cakes of gold in the vaults of the Bank of England a couple

of hundred yards ahead of them. Money was the bills of exchange the bankers and merchants had despatched across the five continents, the fine wrapping paper that enclosed English domination of the

world’s trade. Money was to be counted in banking halls and insurance companies and discount houses, the daily traffic measured out line by line and figure by figure in the great ledgers

which stored its passing.

The Market was different. If Money was cold, the Market was mercurial. She was like a spirit that flew across Leadenhall Street and Crooked Friars, across Bishopsgate and Bengal Court, turning

in the air and changing her mind as she travelled across her City. Some older heads in the great banking houses said she could be like a volcano, erupting with terrible force to shake the very

foundations of finance. There were many who claimed to know the Market’s moods, when she would change her mind, when she would grow sullen and petulant, when she would dance in delight across

the Stock Exchange and bring sudden wealth with floods of speculation about gold or diamonds found in distant parts of the world. The optimists believed the Market was always going to smile on

them. She did not. The cautious and the prudent believed she was a fickle mistress, never to be wholly trusted. Their fortunes might have grown more slowly than the optimists, but they were never

wiped out.

A sudden scream cut through the silent meditations of the marching army. Towards the further bank a tall young man was yelling and pointing to something in the water, his face unnaturally white

against the black of his clothes.

‘There! Look there, for the love of God!’

He pointed at something bobbing about in the water, bumping against the side of one of the ships moored on the City side of the river. Behind the young man there was a hurrying forward as the

slow march transformed itself into double quick time. ‘Look! It’s a body, by the side of the ship, there!’

All around him brokers and merchants and commission agents pushed forward to peer into the water. Two sailors of foreign extraction appeared on deck and stared uncomprehendingly at the

crowd.

‘There’s a corpse in the river! There’s a corpse in the river!’ The phrase spread quickly back across the bridge. Within three minutes word would reach the incoming

passengers in London Bridge station. Within five minutes it would flash past Wellington’s statue and reach the portals of the Royal Exchange.

The tall young man stretched even further forward towards the murky waters of the Thames.

‘Oh, my God!’ he shouted. He fell backwards into the crowd and fainted away into the amazed arms of a fat and prosperous old gentleman who was surprised at how light he was.

The young man was the first to see that the body had no head, and that the hands had been cut off. A grisly stump of neck, clotted yellow and black, was inching its way towards the further

shore.

Murder had come to the City at half-past eight on a Thursday morning.

Throughout the day rumour was King. Rumour, of course, was usually King in the temples of finance: rumours of revolutions and defaults in South America, rumours of unrest and

instability in Russia, and, most frequent and most unsettling of all, rumours of changes in interest rates. But on this day one question and one question only dominated all conversations. Who was

the dead man? Where had he come from? Why did he have no head and no hands? At lunchtime in the chop houses and the private dining rooms it reached its crescendo.

The tall thin young man, Albert Morris, was a hero for twenty-four hours. Revived by brandy and water in the partners’ room of the private banking house where he earned his daily bread, he

told his story over and over again. He told it to his colleagues, he told it to his friends, he told it eagerly to the newspapermen who laid siege to his bank until he was delivered up to them.

The first rumour, believed to have come originally from the Baltic Exchange, was that the corpse was a Russian princeling, a relative of the Tsar himself, murdered by those foul revolutionaries,

the body transported from St Petersburg to London and thrown over the side. The head, said the Baltic Exchange, had been removed so the Russian authorities would never know he had been murdered,

thus forestalling any of those fearful reprisals for which the Tsar’s secret police were famous.

Nonsense, came the counter-rumour from one of the great discount houses. The corpse was not a Russian, he was French. He was a wine merchant from Burgundy who had been carrying on an affair with

another man’s wife. The cuckolded husband, the discount house version went on fancifully, unable to avail himself of the service of the official guillotine, had chopped off the head which had

looked at his wife and the hands which had caressed her body. The corpse had been packed in with a consignment of Burgundy’s finest and thrown into the river.

The last, and most ominous, rumour came from Home Rails on the Stock Exchange. This was the rumour that struck most terror into the small, but growing, female population of the City. Jack the

Ripper is back, claimed Home Rails. They nearly caught him when he went for all those loose women in the East End. Now he’s going for men. This is only the beginning. More decapitated males

were to be expected, dumped in the docks or carried upstream towards Westminster. Beware the Ripper!

The man charged, for now, with the responsibility of finding out the truth about the headless and handless corpse was sitting in his tiny office at Cannon Street police

station. He was suffering, he knew, from his normal feelings of irritation and anger as he looked at his younger colleague.

Inspector William Burroughs was in his late forties. He was a stocky man with a small rather straggly moustache and tired brown eyes. Earlier in his career he had been involved in a successful

murder investigation, and the reputation of being good with cases involving sudden death had stuck with him. But Burroughs knew that had been a fluke. An unexpected confession had solved the crime,

not his detective skills. He had told his wife this many times, and as many times she had instructed him not to tell his superiors.

There are men who look good in uniform, men who carry it off well, men who can appear like peacocks on parade. Burroughs was not one of those. There always seemed to be a button undone, trousers

not sitting properly, a tie adrift at the neck. His sergeant, on the other hand, always looked immaculate, like his bloody mother had washed and ironed him five minutes before, as Burroughs liked

to tell himself. Sergeant Cork was still gleaming in his pristine state at half-past twelve on the morning when the body was found.

A couple of sailors had propelled the corpse gently towards the riverbank with a boathook. Inspector Burroughs had supervised the landing, blankets at the ready to cover the dead man. He had

ridden with it to the morgue at St Bartholomew’s Hospital and delivered it into the care of the doctors. They had promised him a preliminary report

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...