- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

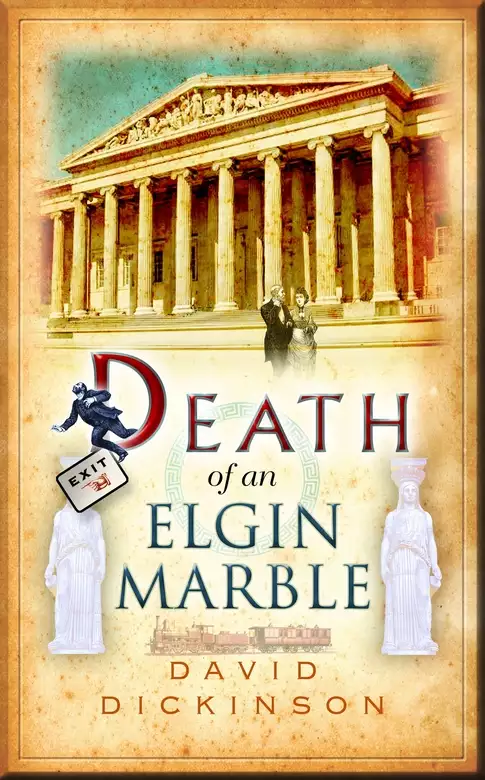

Synopsis

The British Museum in Bloomsbury is home to one of the Caryatids, a statue of a maiden that acted as one of the six columns in a temple which stood on the Acropolis in ancient Athens. Lord Elgin had brought her to London in the nineteenth century, and even though now she was over 2,300 years old, she was still rather beautiful - and desirable. Which is why Lord Francis Powerscourt finds himself summoned by the British Museum to attend a most urgent matter. The Caryatid has been stolen and an inferior copy left in her place. Powerscourt agrees to handle the case discreetly - but then comes the first death: an employee of the British Museum is pushed under a rush hour train before he and the police can question him. What had he known about the statue's disappearance? And who would want such a priceless object? Powerscourt and his friend Johnny Fitzgerald undertake a mission that takes them deep into the heart of London's Greek community and the upper echelons of English society to uncover the bizarre truth of the vanishing lady...

Release date: November 7, 2017

Publisher: Constable

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Death of an Elgin Marble

David Dickinson

The Caryatid was part of the Elgin Marbles, a glittering treasure trove of ancient statuary that had once graced the walls of the Parthenon, the most prominent building on the High City, the Acropolis, of Athens, 2,400 years ago. All of the works had been seized by the British Ambassador to Turkey, Lord Elgin, at the beginning of the nineteenth century and carried back to Britain. For just over a century the Elgin Caryatid, tall, graceful and rather severe, had stood in her place in the Elgin Rooms to delight and entrance the population of London.

The Caryatid was a statue of a maiden or a young girl that took the place of one of six columns or pillars in the Erechtheion, a temple that had stood near the Parthenon. This Caryatid was the only one to have been taken by Lord Elgin – her sisters were not to be found in London. Seven feet six inches tall, the statue was wearing a floor length sleeveless marble dress, carved like a tunic at the top and hanging in elaborate folds at her waist. She had a look of haughty pride on her face, as if only she and her five colleagues were fit to represent their city in its place of greater glory. Lord Elgin, hero or villain of the Marbles that bore his name, depending on your point of view, was in the habit of saying to his friends, ‘That Caryatid filly, she looks rather a handful to me.’ She had lived as a single Caryatid for over a hundred years since she came to London and was now about 2,300 years old. In the lifetime of the current generation of British Museum porters, always keen on some form of intimacy with their lifeless charges, the Caryatid had been known as Charlotte, or Charlie, Clare or Clary, Cristobel or Chrissie, Carmen or Carrie. The oldest porter on the staff had always thought that Carmen Caryatid had a good ring to it. The Head of Greek and Roman Antiquities called her Clytemnestra. The Director of the British Museum, more faithful perhaps to an English literary tradition, called her Clarissa, Clarissa the Caryatid.

The American was Stephen Lambert Lodge, a thirty-year-old lecturer in Architecture at Yale, one of the oldest and most distinguished universities in America. He was beginning a tour of the cities of Europe that held fragments of the Parthenon, for many cultural pirates apart from Lord Elgin had helped themselves to fragments of fallen statues or ripped them from the walls. From London and the British Museum he was travelling to the Louvre in Paris and on to Munich and finally to Athens itself. Lambert Lodge had arrived at the British Museum on the morning of his great discovery in a state of high excitement. He had been thinking about this trip for two years now and planning his itinerary for nine months before he stepped off his liner in Southampton and onto the train for London. He was saving the Caryatid till near the end. As he stared at the battles between the Centaurs and the Lapiths and the procession of maidens and young men and the charioteers and the sacrifices from the Parthenon frieze, he felt a sense of exultation, that he had, in some strange way, come home at last in a city that was over three thousand miles from New Haven, Connecticut. He looked at the statue for a long time. He pulled a magnifying glass out of his pocket for a more detailed examination. Lambert Lodge spent nearly two hours with the Caryatid, walking round her, peering intently at the marble. He stroked the long robe with its delicate folds that flowed from the young lady’s waist. It was the stroking that confirmed to the attendant on duty that this latest visitor was probably insane and certainly needing intercepting before he embraced the Caryatid and conducted intimate relations with her on the museum floor.

‘Excuse me, sir,’ said the attendant, who was called Philip Jones and came from Highbury, ‘what exactly do you think you are doing?’

‘I do beg your pardon, sir,’ said Lambert Lodge, ‘I know my behaviour must seem rather odd. My apologies. My card, sir.’

He drew a rather elaborate one from his waistcoat which carried the arms of Yale University and his name as lecturer in Architecture at the School of Fine Arts in a rather florid typeface.

‘Forgive me, sir,’ the young American went on, with the politeness inculcated from birth in the old families of Boston to which he belonged, ‘are you an expert in Greek sculpture, by any chance?’

‘I’m afraid I’m not, sir,’ Jones replied, ‘the missus says the only thing I am an expert in is the fixture list for Tottenham Hotspur and that’s a fact.’

‘I’m sure that’s very valuable information,’ said Lambert Lodge with a smile, ‘but I do happen to be something of an expert on ancient statues and things like that. Do you think you could be very kind and show me the way to your director’s office? I have something very important to discuss with him.’

‘Of course, sir, seeing you’re an academic gentleman, you’d be surprised how many of them we get in here, forgetting their documents and their umbrellas, most of them. I can’t take you to the Director’s office, since he’s not here, and neither is the Head of Greek and Roman Antiquities, but the Deputy Director is in, sir, I saw him not half an hour ago. Would he do?’

‘Splendid,’ said Lambert Lodge. ‘How very kind. Could you take me to him at once?’

Five minutes later the American was ushered into a large office looking out over the great steps and the front of the British Museum where the pilgrims milled about, smoking cigarettes and discussing the treasures they had seen before returning to the more mundane surroundings of omnibus and underground railway. A hundred and fifty yards behind him in the Reading Room young scholars were struggling with their theses and European revolutionaries were composing incendiary tracts far from the eyes of their country’s secret police. The Deputy Director ushered Lodge to a chair on the left of the fireplace.

‘This is indeed a pleasure, Mr Lodge,’ he began. ‘I have read one or two of your learned articles, I believe.’

‘You are too kind, sir,’ cried Lodge, stretching out his long legs. Theophilus Ragg, the Deputy Director, was a stooped man of average height in his early sixties with grey hair turning to white and a small, well-trimmed moustache. He was wearing a dark suit with a white shirt and a Balliol College tie. Inspecting him, Lodge thought he looked like a small town undertaker somewhere in the vast obscurity of the Midwest, waiting for retirement and fearful of more time with his family.

‘What can I do for you this morning, Mr Lodge? The Director is in the Middle East and the Head of Greek and Roman Antiquities is with a party in the Alps, I fear.’

Lodge wondered if the ancient treasures of some long extinct tribe were going to be removed from the sands of Mesopotamia and brought back to join the other totems adorning the Bloomsbury museum.

‘I’d like to ask you about the Caryatid in the Elgin Room, if I might, sir,’ said Lodge, trying to sound as emollient as possible.

‘Please do,’ said Theophilus Ragg.

‘I’m afraid what I’m about to say may come as something of a shock, Mr Ragg. I’m not absolutely sure, but I don’t think your Caryatid is real. I don’t think she’s the real McCoy, if you’ll forgive me. Let me explain. It may be there is a reason for this. Perhaps the real statue is away being cleaned or restored?’

‘No, she’s not,’ said Ragg, pulling nervously at his moustache. ‘Pray continue.’

‘Believe me, Mr Ragg,’ Lodge continued, ‘I have no wish to cause trouble for you or your great museum here. My reason has to do with the marble. The real Caryatid, like all the statues here from the Acropolis, is carved out of Pentelic marble, brought to Athens from Mount Penteli in Attica all those years ago. Your Caryatid is made from Parian marble, very similar, but not quite the same. There are many ancient works carved in the white marble from Paros, but the metopes and the frieze and the Caryatid from the Parthenon are not among them. The Building Research Program at Yale put on an exhibition three years ago of examples of the different sorts of marble used by the Greeks, the Romans and the great sculptors of the Renaissance. Maybe they hoped to encourage a new golden age in American sculpture, who knows. Anyway, Mr Ragg, I was able to touch and get the feel of all these different types of marble. Pentelic and Parian marble are similar, pure white and fine grained. But the Pentelic, from the Penteliko Mountain, is semi-translucent, the other one is not. Even after all this time you can just see the difference.’ He paused.

The Deputy Director was writing very carefully in a large black notebook.

‘I’m so sorry,’ the young American concluded.

The Deputy Director stared into the middle distance, looking once more, Lodge thought, like the ageing Midwest undertaker, searching for a missing coffin perhaps, lost in the press of traffic between church and cemetery, the few mourners stamping their feet and peering down the yew trees that lined the drive.

‘Maybe it’s just a mistake,’ he whispered, ‘I expect she’ll turn up in the end.’

‘What can I do to help, sir? I am in London for about a week and could stay longer if that would be useful. I’m desperately sorry to have been the bearer of such bad news.’

Theophilus Ragg sighed. ‘You have been most kind, Mr Lodge. Don’t think I am not grateful. I’m just shocked, that’s all. I shall have to conduct an inquiry to see if our experts agree with you and find out what has happened. We need to know how long ago the switch happened, if it did, and what we would have to do to make sure it could never happen again.’

‘Could I just ask you about the Head of Greek and Roman Antiquities, Mr Ragg? Will he be back soon? I should so like to meet him, you see. We have heard so much about him in New England.’

‘Dr Tristram Stanhope, you mean?’ Ragg replied, suddenly ceasing to doodle in his notebook. ‘I think he should be back soon. He is still suffering from youth, you know, suffering rather badly, I should say.’

‘Suffering from youth, sir? I’m not quite sure what you mean.’

‘Forgive me, I may not have expressed myself very well. When you have lived in seats of learning like Oxford and the British Museum, you watch the rhythm of the passing generations. There are fresh drafts of the young every autumn, of course, the hope of youth coursing through their veins. But you look at the dons as they too grow older. By the time they reach middle age the hopes of youth have been replaced with some kind of accommodation with this complicated world. Stanhope is in his middle forties now. You would expect him to have passed through the hope and the optimism of youth. But no, he still behaves as if he were twenty-one years old. Never mind. We have more important things to think about now.’

The young American felt his time was up. ‘I am staying at Brown’s Hotel, Mr Ragg. Just leave a message if I am not there and I will come at any hour of day or night.’

Stephen Lambert Lodge bowed slightly as he left. As he made his way out towards the front door, he heard the plaintive cry once more. ‘Maybe it’s just a mistake, I expect she’ll turn up in the end.’

The behaviour of the Deputy Director, left on his own, would have surprised Lodge. He shuffled next door into the Director’s office and locked the door. He searched in the desk until he found a small, dark blue address book. He copied the phone numbers and the addresses given there for members of the Maecenas Club, a small but select group of the top museum directors in London: National Gallery, the Tate, Natural History Museum, the Science Museum, the Victoria and Albert. The institution was named after the great artistic impresario Maecenas who worked for the first Roman Emperor Augustus, persuading poets like Virgil to compose works that would add to the lustre of Rome and the glory of Augustus. Members met in a private room at the Athenaeum once every three months. In emergencies, special meetings or special assistance could be called at twenty-four hours’ notice. This was what Theophilus Ragg proposed to do. He had to find a man who would bring his Caryatid back. He had no faith at all in the ability of the police to do it. One of these directors, surely, somewhere in their career must have needed a specialist who could solve a crime discreetly and without fuss. Money would be no object. The Maecenas members must help solve his problem. He gave no indication of what had happened when he wrote to the museum directors. He merely asked if, in the course of their professional lives, they had occasion to have recourse to a private investigator. The British Museum, he told them, needed the finest in the country and they needed him in the next twenty-four hours.

Few car salesmen have ever owned a house on the fashionable Old Mile at Ascot and maintained a stable of racehorses, thus keeping a foot, or hoof, in the quickest delivery of the oldest and the newest forms of human transportation at the same time. Octavius Stratton was also the sole representative of his tribe to ride to Ascot with the King in the Royal Landau. On this bright morning he was taking Lord Francis Powerscourt and his son Thomas for a drive in a new Daimler. Octavius, who really was the eighth child of his parents, was usually known as Eugene. He was a second cousin twice removed of Powerscourt’s wife, the mother of Thomas Powerscourt, Lady Lucy. Stratton was confident that his family connections would help deliver what would, for him, be a profitable sale. The Daimler was the finest car in its class, he assured the Powerscourts. It might be unfashionable to say so, he virtually whispered at this point in case he was overheard at the northern end of Hampstead High Street, but German engineering would soon be recognized as the best in the world. He regaled his clients with accounts of the great speed the vehicle could attain, its record as a hill climber in the annual Shelsley Walsh Hill Climb in Worcestershire, and a barrage of statistics about brake horse power, transmission and engine size. Octavius might have been slightly alarmed had he seen Thomas Powerscourt in the back seat taking extensive notes on his shirt cuffs about the mechanical details. For the young man was one of the best mathematicians Westminster School had produced this century. He was the finest shot of his year in the public schools rifle shooting championships and fluent in both French and German. This was his last term at school, with the entrance exams for Cambridge a couple of months away. Thomas began staring very hard at the driver’s back.

The cart was a nondescript sort of vehicle. It could have been carrying barrels of beer or crates of sausages. Nobody would have looked at it twice. The two men were wearing the most nondescript clothes they could find, dark trousers, shirts that had once been white and boots that had seen better days. They might have been a couple of shepherds taking their wares to market. But in the back of the van there were no sheep. There was a long, heavy bundle swathed in blankets and other soft materials going to a place that was a long way from the British Museum. They were in the Welsh mountains now, making for their destination, a large house near a series of caves in the Black Mountains of the Brecon Beacons. The two men had no idea what their cargo was. For them, it was just another package. They spent most of their days moving packets and parcels of one sort or another from place to place.

Theophilus Ragg went to the stationery cupboard after he had despatched his letters. He took out a large new black notebook and wrote the day’s date on the inside cover in red ink. He began a doodle on the opening page and stared out of his window. He had asked his experts for their views and he knew he had to wait for their report but he felt sure the young American was right. Where was the wretched Caryatid now? Was she still in one piece? Who on earth could have taken her? How on earth had they taken her? Where had they found a replacement? Had they made more than one?

Ragg had started his life after taking his degree at Oxford as a teacher of classics and junior housemaster at one of Britain’s leading public schools. After three or four years he found the prevailing spirit of hearty athleticism tinged with what he privately termed ‘the traditions of the philistines’ more than he could bear. He longed to hear eulogies of the odes of Pindar rather than of the triumphs of the football team and the military values of the combined cadet force. When a position was advertised as a Junior Fellow at one of the smaller Oxford Colleges, lecturing on textual criticism in the ancient Greek tragedians, Theophilus was accepted immediately. The conversation at the Shrewsbury College High Table, he told his parents, certainly took a turn for the better after the banalities of the school common room. Theophilus’s talents as an organizer, if not of genius, then certainly of very remarkable powers, only came about by accident. The College Bursar, an expert in the poetry of Sir Philip Sidney, dropped dead of heart failure at four thirty one summer’s day in the Fellows Garden, just as the dons in residence had assembled for afternoon tea. The Warden, a deeply impatient historian who regarded all his colleagues as ignorant fools, sought among his fellows for a replacement. Of newcomer Ragg he knew nothing at all. This was a virtue. He was appointed to the post immediately.

Like most great generals, Ragg moved slowly at first. He spent an entire term observing the working lives of the college staff, the cooks, the porters, those who waited at table and those who cleaned the young gentlemen’s rooms. Their hours and their movements were all written down in his notebook. When the workers returned to Shrewsbury for the Hilary Term, their hours had been changed. There were fewer of them. Most were working slightly longer hours than before. All were better paid than in the past. The College made considerable savings. Over the years Ragg turned his attention to other questions of detail, the supply of food and drink to the College and its members, where he discovered a mass of swindles and petty corruption, to the costs of maintaining the ancient buildings where he replaced most outside contractors with permanent masons and carpenters employed directly by the College. Eventually, after fifteen years in post, he screwed up his courage and asked the Warden, now a genial theologian with a great weakness for Château Margaux, if he could take a look at the College investments and financial strategy. The usual progress, slow but well thought out, was followed. By now, Theophilus Ragg, who had originally been a figure of fun, taking detailed notes of the college laundry lists as his early critics maintained, was the hero of the hour, particularly among the better informed heads of Oxford houses who regarded him as a financial Clausewitz and tried to lure him away to their own establishments. Ragg turned down all positions of bursar or newer, even grander, titles invented specially for him, at Merton, Lincoln, Exeter and New College. Only one institution was able to lure him away, and that was, in part, because it was an old boy of his own college who made the offer.

Andrew Cronan had read Classics at Shrewsbury. Ragg had been his tutor and had treated him well. When he became Director of the British Museum, Cronan realized that the administration of his empire was in chaos with costs out of control and prima donnas and private satrapies rampant among the Hittites and the Assyrians. But he thought he needed a bait to draw Ragg down to London. The museum had, somewhere in its vast archive, a store of the manuscripts of ancient Greek philosophers and playwrights. Early editions of Aristotle and Aristophanes and Aeschylus were snuggled down in the basements beneath the pavements of Great Russell Street and the regular traffic of the Piccadilly Line. He asked Ragg to combine the roles of bursar and archivist at a salary rather greater than that of most of the heads of Oxford colleges. Cronar knew the high costs would be recouped many times over. And he enlisted an important ally, one whose very existence always brought on dark sighs of ‘Who would have thought it?’ or ‘Well, I never,’ or even ‘I haven’t heard of anything so remarkable this year or last.’ Cronan’s ally was the key factor in Ragg’s decision to move. For, to the astonishment of his peers, he had, some years before, secured for himself a most beautiful wife who produced a small phalanx of equally beautiful children. Christabel Ragg was determined to conquer the larger field of literary London as she already had the academic communities of north Oxford. She would become, she told her husband proudly, the Zuleika Dobson of High Holborn and Sicilian Avenue.

After a quick trip up the Great North Road where the Daimler could show its paces, the little party returned to Markham Square. Octavius Stratton was hardly out of the Powerscourt front door when Thomas grasped his father firmly by the arm and made him promise not to buy the car. It was, Thomas assured his parent, a very bad investment. Octavius’s parents might have been very successful in the numbers of children produced, but their eighth had no grasp of figures or of engineering principles. If the physical details of the Daimler’s engine, as described by Stratton, were correct, said Thomas, shaking his light brown curls sadly as he spoke, the car would probably go backwards. Or possibly even sideways.

Powerscourt suddenly remembered the elation with which Thomas had greeted the arrival of the Rolls Royce Silver Ghost, the family’s first motor car, several years before. He would huddle into the corner of the back seat, his cap firmly placed on his head, and wave at the passing pedestrians condemned to travel by foot and even at the cows and the sheep in the Home Counties countryside. Once Thomas had disappeared completely from the house in Markham Square. It was some hours before he was discovered, sitting happily on the back seat of the Silver Ghost, doing his homework.

Thomas was prepared to carry on about the Daimler for some time when his mother appeared and gave Powerscourt a small cream envelope. This requested him to present himself at the address at the top of the page as soon as possible. It was a matter of the greatest consequence. It could, the writer said, be described without exaggeration as a matter of the utmost national importance. The author looked forward to seeing Powerscourt within the hour. The signature was that of Theophilus Ragg, Deputy Director and Principal Librarian of the British Museum, Great Russell Street, London WC.

The old port in Corfu is guarded by an ancient fort, one of two that stand sentinel over the island’s capital. The harbour front has the usual collection of cafés, bars, rundown tavernas and ship chandlers offering to sell you anything from fresh cordage to tinned food that will last for months in the hold of your vessel. And, hard by the oldest and most disreputable bar, the Hermes, stood a branch of the telegraph office. Sitting at a little table under the broken shade of the Hermes, a Greek sea captain was refilling his glass with ouzo and staring moodily out to sea. He was waiting for a message. He had been waiting for two days already but he knew he would wait as long as it took for the message to arrive. There was, he had been promised, a generous commission, a very generous commission awaiting him.

Captain Dimitri’s vessel, in theory, was a seaborne circus, travelling with her entertainments back and forth through the Corinth Canal, across the island towns and cities of the Aegean and the Ionian Seas. Sometimes she carried things that had little to do with circuses.

The ship was old and dirty, the paintwork peeling with age, the sails no longer white but flecked with streaks of grey. There was a mangy lion in a twisted cage by the main cabin, flanked by a couple of querulous monkeys. A pair of jugglers practised with dirty plates, specially hardened in taverna ovens so they would not break. A dark acrobat tumbled about in the rigging from time to time. All kinds of strange-looking packages went aboard the first day, amphorae, presumably filled with wine that might have been thousands of years old, tiny decorated vessels filled with honey that could have inspired a poet to write an ode to a Grecian urn. The Captain spat expertly into the oily waters of the little harbour and refilled his glass. The message had not come yet, but the ouzo was cheap, the taverna served a fine if rather greasy moussaka, and the waitress, daughter of the house, was of remarkable beauty. Captain Dimitri prepared himself for a long wait.

Theophilus Ragg, Deputy Director of the British Museum, led Powerscourt straight to the last known home of the missing Caryatid. He didn’t let Powerscourt linger long by the replacement. He took him straight back to his office without saying a word. Only when he was sitting opposite his visitor on a long sofa in the centre of his office did Ragg speak. The Caryatid Powerscourt had just seen was a fake. British Museum staff had, with great reluctance, admitted to the Deputy Director that the American was correct. The original had been stolen, possibly during a fire alarm the week before. The only people who knew about it were the American scholar who had discovered the switch, now sworn to silence and awaiting instructions in Brown’s Hotel, and the Deputy Director himself. The Director himself was out of contact in the Middle East on a shopping expedition and not expected to return for some time. Would Powerscourt take on the case? Would he find the Caryatid? He would? Excellent. He, Deputy Director Ragg, would be happy to answer questions for the rest of the day, if need be.

Powerscourt began with the most obvious query. Why had the Director not sent for the police? Surely there must be stipulations in the insurance and so on? My decision and mine alone, the Deputy Director replied sadly. Men in uniform tramping through the museum would attract attention. The matter would appear in the newspapers. Publicity in a case as important as this could be ruinous. Other thieves might come calling for other treasures. The nation’s cultural heritage was in danger. Lord Powerscourt should be aware that this Caryatid was the best preserved of her kind in the world. She was unique.

‘Let me remind you, Lord Powerscourt, that it is only weeks now since the Mona Lisa was stolen from the Salon Carré in the Louvre. I do not know if you are aware of the tremendous outcry that has convulsed the city. The Parisian press have reports on the search for the criminal every day. Our own newspapers are also convulsed by the theft. The Director and staff of the Louvre have been vilified in a way France has not seen since the Dreyfus Affair. There is still no sign of the painting. Do you think we at the British Museum wish to be engulfed in such a firestorm? Our Caryatid may not be as famous as the Mona Lisa of Leonardo but she is still the finest example of her kind in the world.’

Powerscourt thought that the Museum Deputy Director was old and close to retirement. The prospect of a repeat of the controversy in Paris had turned his bones to water. He was a man of scholarship, not of the wider world that swirled around outside the walls of his museum. Theophilus Ragg could not, for the moment, see beyond the scandal that could ruin his reputation and sully his last days in office beyond repair. It was to be over a week before Powerscourt realized, as he told Lady Lucy rather sadly later on, that Ragg was not a brittle tree, liable to fall in the first gales of winter, but an oak, a sturdy oak that would be left standing long after the storms had passed.

Powerscourt reminded the Deputy Director, as gently as he could, that the Metropolitan Police were perfectly capable of appearing in plain clothes and being discreet. His new employer seemed astonished to hear of the existence of a plain clothes policeman. Caryatids, said Powerscourt, wore long sleeveless dresses with great folds at the waist. Greek heroes on the Parthenon frieze wore short tunics with swords to kill their enemies. Some policemen went about in dark uniforms with helmets. Some did not. Each to his allotted station.

Treading carefully now, Powerscourt asked what seemed to him at this early stage the two most important questions. How much was the Greek lady worth? And who might want to steal her?

She was priceless, Ragg said after a long pause, staring down at his notebook. Neither the finest bursar in Oxford or Cambridge nor London’s most experienced art auctioneer could put a price on a Caryatid. The Deputy Director could not imagine. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...