- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

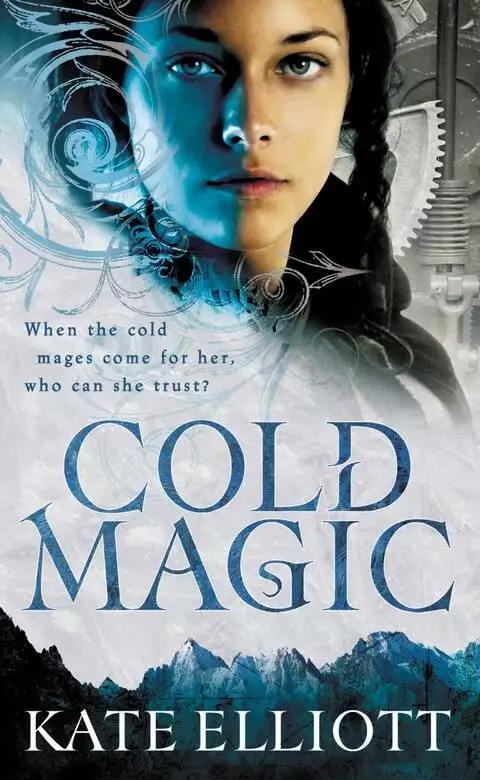

Synopsis

The Wild Hunt is stirring - and the dragons are finally waking from their long sleep...

Cat Barahal was the only survivor of the flood that took her parents. Raised by her extended family, she and her cousin, Bee, are unaware of the dangers that threaten them both. Though they are in beginning of the Industrial Age, magic - and the power of the Cold Mages - still hold sway.

Now, betrayed by her family and forced to marry a powerful Cold Mage, Cat will be drawn into a labyrinth of politics. There she will learn the full ruthlessness of the rule of the Cold Mages. What do the Cold Mages want from her? And who will help Cat in her struggle against them?

Release date: September 9, 2010

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 544

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Cold Magic

Kate Elliott

Or at least, that’s how the dawn chill felt in the bedchamber as I shrugged out from beneath the cozy feather comforter under

which my cousin and I slept. I winced as I set my feet on the brutally cold wood floor. Any warmth from last evening’s fire

was long gone. At this early hour, Cook would just be getting the kitchen’s stove going again, two floors below. But last

night I had slipped a book out of my uncle’s parlor and brought it to read in my bedchamber by candlelight, even though we

were expressly forbidden from doing so. He had even made us sign a little contract stating that we had permission to read

my father’s journals and the other books in the parlor as long as we stayed in the parlor and did not waste expensive candlelight

to do so. I had to put the book back before he noticed it was gone, or the cold would be the least of my troubles.

After all the years sharing a bed with my cousin Beatrice, I knew Bee was such a heavy sleeper that I could have jumped up

and down on the bed without waking her. I had tried it more than once. So I left her behind and picked out suitable clothing from the wardrobe: fresh drawers, two layers of stockings, and a knee-length chemise over which

I bound a fitted wool bodice. I fumblingly laced on two petticoats and a cutaway overskirt, blowing on my fingers to warm

them, and over it buttoned a tight-fitting, hip-length jacket cut in last year’s fashionable style.

With my walking boots and the purloined book in hand, I cracked the door and ventured out onto the second-floor landing to

listen. No noise came from my aunt and uncle’s chamber, and the little girls, in the nursery on the third floor above, were

almost certainly still asleep. But the governess who slept upstairs with them would be rousing soon, and my uncle and his

factotum were usually up before dawn. They were the ones I absolutely had to avoid.

I crept down to the first-floor landing and paused there, peering over the railing to survey the empty foyer on the ground

floor below. Next to me, a rack of swords, the badge of the Hassi Barahal family tradition, lined the wall. Alongside the

rack stood our house mirror, in whose reflection I could see both myself and the threads of magic knit through the house.

Uncle and Aunt were important people in their own way. As local representatives of the far-flung Hassi Barahal clan, they

discreetly bought and sold information, and in return might receive such luxuries as a cawl—a protective spell bound over

the house by a drua—or door and window locks sealed by a blacksmith to keep out unwanted visitors.

I closed my eyes and listened down those threads of magic to trace the stirring of activity in the house: our man-of-all-work,

Pompey, priming the pump in the garden; Cook and Aunt Tilly in the kitchen cracking eggs and wielding spoons as they began the day’s baking. A whiff of smoke tickled

my nose. The tread of feet marked the approach of the maidservant, Callie, from the back. By the front door, she began sweeping

the foyer. I stood perfectly still, as if I were part of the railing, and she did not look up as she swept back the way she

had come until she was out of my sight.

Abruptly, my uncle coughed behind me.

I whirled, but there was no one there, just the empty passage and the stairs leading up to the bedchambers and attic beyond.

Two closed doors led off the first-floor landing: one to the parlor and one to my uncle’s private office, where we girls were

never allowed to set foot. I pressed my ear against the office door to make sure he was in his office and not in the parlor.

My hand was beginning to ache from clutching my boots and the book so tightly.

“You have no appointment,” he said in his gruff voice, pitched low because of the early hour. “My factotum says he did not

let you in by the back door.”

“I came in through the window, maester.” The voice was husky, as if scraped raw from illness. “My apologies for the intrusion,

but my business is a delicate one. I am come from overseas. Indeed, I just arrived, on the airship from Expedition.”

“The airship! From Expedition!”

“You find it incredible, I’m sure. Ours is only the second successful transoceanic flight.”

“Incredible,” murmured Uncle.

Incredible? I thought. It was astounding. I shifted so as to hear better as Uncle went on.

“But you’ll find a mixed reception for such innovations here in Adurnam.”

“We know the risks. But that is not my personal business. I was given your name before I left Expedition. I was told we have

a mutual interest in certain Iberian merchandise.”

Uncle’s voice got sharper without getting louder. “The war is over.”

“The war is never over.”

“Are you behind the current restlessness infecting the city’s populace? Poets declaim radical ideas on the street, and the

prince dares not silence them. The common folk are like maddened wasps, buzzing, eager to sting.”

“I’ve nothing to do with any of that,” insisted the mysterious visitor. Too bad! I thought. “I was told you would be able to help me write a letter, in code.”

My heart raced, and I held my breath so as not to miss a word. Was I about to tumble onto a family secret that Bee and I were

not yet old enough to be trusted with? But Uncle’s voice was clipped and disapproving, and his answer sadly prosaic.

“I do not write letters in code. Your sources are out of date. Also, I am legally obligated to stay well away from any Iberian

merchandise of the kind you may wish to discuss.”

“Will you close your eyes when the rising light marks the dawn of a new world?”

Uncle’s exasperation was as sharp as a fire being extinguished by a blast of damp wind, but my curiosity was aflame. “Aren’t

those the words being said by the radicals’ poet, the one who declaims every evening on Northgate Road? I say, we should fear the end of the orderly world we know. We should fear being swallowed by storm and flood until

we are drowned in a watery abyss of our own making.”

“Spoken like a Phoenician,” said the visitor with a low laugh that made me pinch my lips together in anger.

“We are called Kena’ani, not Phoenician,” retorted my uncle stiffly.

“I will call you whatever you wish, if you will only aid me with what I need, as I was assured you could do.”

“I cannot. That is the end of it.”

The visitor sighed. “If you will not aid our cause out of loyalty, perhaps I can offer you money. I observe your threadbare

furnishings and the lack of a fire in your hearth on this bitter-cold dawn. A man of your importance ought to be using fine

beeswax rather than cheap tallow candles. Better yet, he ought to have a better design of oil lamp or even the new indoor

gaslight to burn away the shadows of night. I have gold. I suspect you could use it to sweeten the trials of your daily life,

in exchange for the information I need.”

I expected Uncle to lose his temper—he so often did—but he did not raise his voice. “I and my kin are bound by hands stronger

than my own, by an unbreakable contract. I cannot help you. Please go, before you bring trouble to this house, where it is not wanted.”

“So be it. I’ll take my leave.”

The latch scraped on the back window that overlooked the narrow garden behind our house. Hinges creaked, for this time of

year the window was never oiled or opened. An agile person could climb from the window out onto a stout limb to the wall; Bee and I had done it often enough. I heard the window thump closed.

Uncle said, “We’ll need those locks looked at by a blacksmith. I can’t imagine how anyone could have gotten that window open

when we were promised no one but a cold mage could break the seal. Ei! Another expense, when we have little enough money for

heat and light with winter blowing in. He spoke truly enough.”

I had not heard Factotum Evved until he spoke from the office, somewhere near Uncle. “Do you regret not being able to aid

him, Jonatan?”

“What use are regrets? We do what we must.”

“So we do,” agreed Evved. “Best if I go make sure he actually leaves and doesn’t lurk around to break in and steal something

later.”

His tread approached the door on which I had forgotten I was leaning. I bolted to the parlor door, opened it, and slipped

inside, shutting the door quietly just as I heard the other door being opened. He walked on. He hadn’t heard or seen me.

It was one of my chief pleasures to contemplate the mysterious visitors who came and went and make up stories about them.

Uncle’s business was the business of the Hassi Barahal clan. Still being underage, Bee and I were not privy to their secrets,

although all adult Hassi Barahals who possessed a sound mind and body owed the family their service. All people are bound

by ties and obligations, and the most binding ties of all are those between kin. That was why I kept stealing books out of

the parlor and returning them. For the only books I ever took were my father’s journals. Didn’t I have some right to them, being that they, and I, were all that remained of him?

Feeling my way by touch, I set my boots by a chair and placed the journal on the big table. Then I crept to the bow window

to haul aside the heavy winter curtains so I would have light. All eight mending baskets were set neatly in a row on the narrow

side table, for the women of the house—Aunt Tilly, me, Beatrice, her little sisters, our governess, Cook, and Callie—would

sit in the parlor in the evening and sew while Uncle or Evved read aloud from a book and Pompey trimmed the candle wicks.

But it was the bound book of slate tablets resting beneath my mending basket that drew my horrified gaze. How had I forgotten

that? I had an essay due today for my academy college seminar on history, and I hadn’t yet finished it.

Last night, I had tucked fingerless writing gloves and a slate pencil on top of my mending basket. I drew on the gloves and

pulled the bound tablets out from under the basket. With a sigh, I sat down at the big table with the slate pencil in my left

hand. But as I began reading back through the words to find my place, my mind leaped back to the conversation I had just overheard.

The rising light marks the dawn of a new world, the visitor had said; or the end of the orderly world we know, my uncle had retorted.

I shivered in the cold room. The war is never over. That had sounded ominous, but such words did not surprise me: Europa had fractured into multiple principalities, territories,

lordships, and city-states after the collapse of the Roman Empire in the year 1000 and had stayed that way for the last eight

hundred years and more; there was always a little war or border incident somewhere. But worlds do not begin and end in the steady mud of daily life, even if that mud involves too many petty wars, cattle raids,

duels, feuds, legal suits, and shaky alliances for even a scholar to remember. I could not help but think the two men were

speaking in a deeper code, wreathed in secrets. I was sure that somewhere out there lay hidden the story of what we are not

meant to know.

The history of the world begins in ice, and it will end in ice. So sing the Celtic bards and Mande djeliw of the north whose

songs tell us where we came from and what ties and obligations bind us. The Roman historians, on the other hand, claimed that

fire erupting from beneath the bones of the earth formed us and will consume us in the end, but who can trust what the Romans

say? Everything they said was used to justify their desire to make war and conquer other people who were doing nothing but

minding their own business. The scribes of my own Kena’ani people, named Phoenicians by the lying Romans, wrote that in the

beginning existed water without limit, boundless and still. When currents stirred the waters, they birthed conflict and out

of conflict the world was created. What will come at the end, the ancient sages added, cannot be known even by the gods.

The rising light marks the dawn of a new world. I’d heard those words before. The Northgate Poet used the phrase as part of his nightly declamation when he railed against

princes and lords and rich men who misused their rank and wealth for selfish purposes. But I had recently read a similar phrase

in my father’s journals. Not the one I’d taken out last night. I’d sneaked that one upstairs because I had wanted to reread an amusing story he’d told about encountering a saber-toothed cat in a hat shop. Somewhere

in his journals, my father had recounted a story about the world’s beginning, or about something that had happened “at the

dawn of the world.” And there was light. Or was it lightning?

I rose and went to the bookshelves that filled one wall of the parlor: my uncle’s precious collection. My father’s journals

held pride of place at the center. I drew my fingers along the numbered volumes until I reached the one I wanted. The big

bow window had a window seat furnished with a long plush seat cushion, and I settled there with my back padded by the thick

winter curtain I’d opened. No fire crackled in the circulating stove set into the hearth, as it did after supper when we sewed.

The chill air breathed through the paned windows. I pulled the curtains around my body for warmth and angled the book so the

page caught what there was of cloud-shrouded light on an October morning promising yet another freezing day.

In the end I always came back to my father’s journals. Except for the locket I wore around my neck, they were all I had left

of him and my mother. When I read the words he had written long ago, it was as if he were speaking to me, in his cheerful

voice that was now only a faint memory from my earliest years.

Here, little cat, I’ve found a story for you, he would say as I snuggled into his lap, squirming with anticipation. Keep your lips sealed. Keep your ears open. Sit very, very still so no one will see you. It will be like you’re not here but

in another place, a place very far away that’s a secret between you and me and your mama. Here we go!

Once upon a time, a young woman hurried along a rocky coastal path through a fading afternoon. She had been sent by her mother

to bring a pail of goat’s milk to her ailing aunt. But winter’s tide approached. The end of day would usher in Hallows Night,

and everyone knew the worst thing in the world was to walk abroad after sunset on Hallows Night, when the souls of those doomed

to die in the coming year would be gathered in for the harvest.

But when she scaled the headland of Passage Point, the sun’s long glimmer across the ice sea stopped her in her tracks. The

precise angle of that beacon’s cold fire turned the surface of the northern waters into glass, and she saw an uncanny sight.

A drowned land stretched beneath the waves: a forest of trees; a road paved of fitted stone; and a round enclosure, its walls

built of white stone shimmering within the deep and pierced by four massive gates hewn of ivory, pearl, jade, and bone. The

curling ribbons rippling along its contours were not currents of tidal water but banners sewn of silver and gold.

So does the spirit world enchant the unwary and lead them onto its perilous paths.

Too late for her, the land of the ancestors came alive as the sun died beyond the western plain, a scythe of light that flashed

and vanished. Night fell.

As a full moon swelled above the horizon, a horn’s cry filled the air with a roll like thunder. She looked back: Shadows fled

across the land, shapes scrambling and falling and rising and plunging forward in desperate haste. In their wake, driving

them, rode three horsemen, cloaks billowing like smoke.

The masters of the hunt were three, their heads concealed beneath voluminous hoods. The first held a bow made of human bone,

the second held a spear whose blade was blue ice, and the third held a sword whose steel was so bright and sharp that to look

upon it hurt her eyes. Although the shadows fleeing before them tried to dodge back, to return the way they had come, none

could escape the hunt, just as no one can escape death.

The first of the shadows reached the headland and spilled over the cliff, running across the air as on solid earth down into

the drowned land. Yet one shadow, in the form of a lass, broke away from the others and sank down beside her.

“Lady, show mercy to me. Let me drink of your milk.”

The lass was thin and trembling, more shade than substance, and it was impossible to refuse her pathetic cry. She held out

the pail of milk. The girl dipped in a hand and greedily slurped white milk out of a cupped palm.

And she changed.

She became firm and whole and hale, and she wept and whispered thanks, and then she turned and ran back into the dark land,

and either the horsemen did not see her or they let her pass. More came, struggling against the tide of shadows: a laughing

child, an old man, a stout young fellow, a swollen-bellied toddler on scrawny legs. Those who reached her drank, and they

did not pass into the bright land of the ancestors. They returned to the night that shrouded the land of the living.

Yet, even though she stood fast against the howl of the wind of foreordained death, few of the hunted reached her. Fear lashed

the shadows, and as the horsemen neared, the stream of hunted thickened into a boiling rush that deafened her before it abruptly

gave way to a terrible silence. A woman wearing the face her aunt might have possessed many years ago crawled up last of all

and clung to the rim of the pail, too weak to rise.

“Lady,” she whispered, and could not speak more.

“Drink.” She tipped the pail to spill its last drops between the shade’s parted lips.

The woman with the face of her aunt turned up her head and lifted her hands, and then it seemed she simply sank into the rock

and vanished. A sharp, hot presence clattered up. The spearman and the bowman rode on past the young woman, down into the

drowned land, but the rider with the glittering sword reined in his horse and dismounted before she could think to run.

The blade shone so cold and deadly that she understood it could sever the spirit from the body with the merest cut. He stopped

in front of her and threw back the hood of his cloak. His face was black and his eyes were black, and his black hair hung past his shoulders and was twisted

into many small locks like the many cords of fate that bind the thread of human lives.

She braced herself. She had defied the hunt, and so, certainly, she would now die beneath his blade.

“Do you not recognize me?” he asked in surprise.

His words astonished her into speech. “I have never before met you.”

“But you did,” he said, “at the world’s beginning, when our spirit was cleaved from one whole into two halves. Maybe this

will remind you.”

His kiss was lightning, a storm that engulfed her.

Then he released her.

What she had thought was a cloak woven of wool now appeared in her sight as a mantle of translucent power whose aura was chased

with the glint of ice. He was beautiful, and she was young and not immune to the power of beauty.

“Who are you?” she asked boldly.

And he slowly smiled, and he said—

“Cat!”

My cousin Beatrice exploded into the parlor in a storm of coats, caps, and umbrellas, one of which escaped her grip and plummeted

to the floor, from whence she kicked it impatiently toward me.

“Get your nose out of that book! We’ve got to run right now or you’ll be late!”

I ripped my besotted gaze from the neat cursive and looked up with my most potent glower.

“Cat! You’re blushing! What on earth are you reading?” She dumped the gear on the table, right on top of the slate tablets.

“Ah! That’s my essay!”

With a fencer’s grace and speed, Bee snatched the journal out of my hands. Her gaze scanned the writing, a fair hand whose

consistent and careful shape made it easy to read from any angle.

She intoned, in impassioned accents, “ ‘His kiss was lightning, a storm that engulfed her’! If I’d known there was romance

in Uncle Daniel’s journals, I would have read them.”

“If you could read!”

“A weak rejoinder! Not up to your usual standard. I fear reading such scorching melodrama has melted your cerebellum.”

“It’s not melodrama. It’s an old traditional tale—”

“Listen to this!” She slapped a palm against her ample bosom and drawled out the words lugubriously. “ ‘And he slowly smiled,

and… he… said—’ ”

“Give me that!” I lunged up, grabbing for the journal.

She skipped back, holding it out of my reach. “No time for kisses! Get your coat on. Anyway, I thought your essay was…” She

excavated the tablets, flipped them closed, and squinted her eyes to consider the handsomely written title. “Blessed Tanit,

protect us!” she muttered as her brows drew down. She made a face and spoke the words as if she could not believe she was

reading them. “ ‘Concerning the Mande Peoples of Western Africa Who Were Forced by Cold Necessity to Abandon Their Homeland

and Settle in Europa Just South of the Ice Shelf.’ Could you have made that title longer, perhaps? Anyway, what do kisses have to do with the West African diaspora?”

“Nothing. Obviously!” I sat on a chair and began to lace up my boots. “I was thinking of something else. The beginning and

ending of the world, if you must know.”

She wrinkled her nose, as at a bad smell. “The end of the world sounds so dreary. And so final.”

“And I remembered that my father mentioned the beginning of the world in one of his journals. But this was the wrong story,

even though it does mention ‘the world’s beginning.’ ”

“Even I could tell that.” She glanced at the page. “ ‘When our spirit was cleaved from one whole into two halves.’ That sounds

painful!”

“Bee! The entire house can hear you. We’re not supposed to be in here.”

“I’m not that loud! Anyway, of course I spied out the land first. Mother and Shiffa are up in the nursery where Astraea is

having a tantrum. Hanan is on the landing, keeping watch. Father and Evved went all the way out into the back. So we’re safe,

as long as you hurry!”

I plucked the journal from her hand and set it on the table. “You go on ahead to the academy. I just need to write a conclusion.

It’s the seminar the headmaster teaches, and I hate to disappoint him. He never says anything. He just looks at me.” I excavated my slate tablet and pencil from beneath the coats and caps.

Bee shoved my coat onto one of the chairs, searching for her cap. After tying it tight under her chin and pulling on her coat,

she swung her much-patched cloak over all. “Don’t be late or Father will forbid us the trip to the Rail Yard.”

“Which handsome pupil do you intend to flirt with there?”

She launched a glare like musket shot in my direction and strode imperiously from the parlor, not bothering to answer. I wrote

my conclusion. Her little sister Hanan clattered down the stairs with her to bid her farewell by the front door. Up in the

nursery, Astraea had launched into one of her mulish fits of “no no no no no,” and our governess, Shiffa, had reverted to

her most coaxing voice to appease her. Aunt Tilly’s light footsteps passed down the steps to the ground floor and thence back

to the kitchen, no doubt to consult with Cook about finding something sweet to break the little brat’s concentration. I wrote

hurriedly, not in my best script and not with my most nuanced understanding.

That is how those druas with secret power among the local Celtic tribes, and the Mande refugees with their gold and their

hidden knowledge, came together and formed the mage Houses. The power of the Houses allowed them to challenge princely rule

while—

I heard footsteps coming up the stairs, and a key turned in the office door. I paused, hand poised above the slate. Men entered

the office; the door was shut.

Uncle spoke in a low voice no one but me could have heard through the wall. “You were supposed to come at midnight.”

A male voice answered. “I was delayed. Is everything here I paid for?”

“Here are the papers.”

“Where is the book?”

“Melqart’s Curse! Evved, didn’t you get the book?”

“It must still be in the parlor. Just a moment.”

I wiped the “while” from the slate and pressed a hasty, smeared period to the sentence. It would have to do. I scooped up

the slate tablet and my schoolbag, bolted for the door, and got out just as the door between the study and the parlor was

unlocked.

I halted on the landing to listen. Aunt Tilly was back upstairs, speaking with Shiffa about the girls’ lessons for the day

while Astraea whined, “But I wanted yam pudding, not this!” Meanwhile, Hanan had gone back to the kitchen and was chattering

with Cook and Callie in her high, sweet voice as the three began to peel turnips. Pompey, with his distinctive uneven tread,

was in the basement. I fled down the main stairs and out the front door, and it was not until I was out of sight of the house

that I realized I had forgotten my coat, cap, and umbrella. I dared not return to fetch them.

Yet what is cold, after all, but the temperature to which we are most accustomed? It is cold for half the year here in the

north. However pleasant the summer may seem, the ice never truly rests; it only dozes through the long days of Maius, Junius,

Julius, and Augustus with its eyes half closed. I stuffed the tablet in my schoolbag between a new schoolbook and my scholar’s

robe, and kept going. To keep warm, I ran instead of walking, all the way through our modest neighborhood and then up the

long hill into the old temple district where the new academy had been built twenty years ago. Fortunately, the latest fashionable

styles allowed plenty of freedom for my legs and lungs.

As I crossed under the gates into the main courtyard, a fine carriage pulled up to disgorge a brother and two sisters swathed in fur-lined cloaks. Though late like me, they were so rich and well connected that they could walk right in the front

through the grand entry hall without fearing censure, while I fumbled with frozen hands at the servants’ entrance next to

the latrines. The cursed latch was stuck.

“Salve, Maestressa Barahal. May I help you with that?”

I swallowed a yelp of surprise and looked up into the handsome face of Maester Amadou Barry, who had evidently followed me

to the side door. His sisters were nowhere in sight.

“Salve, maester,” I said prettily. “I saw you and your sisters arrive.”

“You’re not dressed for the weather,” he remarked, pushing on the latch until it made a clunk and opened.

“My things are inside,” I lied. “I can’t be late, for the proctor locks the balcony door when the lecture starts.”

“My apologies. I was just wondering if your cousin Beatrice…” His pause was so awkward that I smiled. I was certain he was

blushing. “And you, of course, and your family, intend to visit the Rail Yard when it is open for viewing next week.”

“My uncle and aunt intend to take Beatrice and me, yes,” I replied, biting down another smile. “If you’ll excuse me, maester.”

“My apologies, for I did not mean to keep you,” he said, backing away, for a young man of his rank would certainly enter through

the front doors no matter how late he was.

Inside, as I raced along a back corridor, all lay quiet except for a buzz of conversation from the lecture hall. I had a chance

to get to my seat before it was too late. In icy darkness, I hurried up the narrow steps that led to the balcony of the lecture hall. The proctor

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...