- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

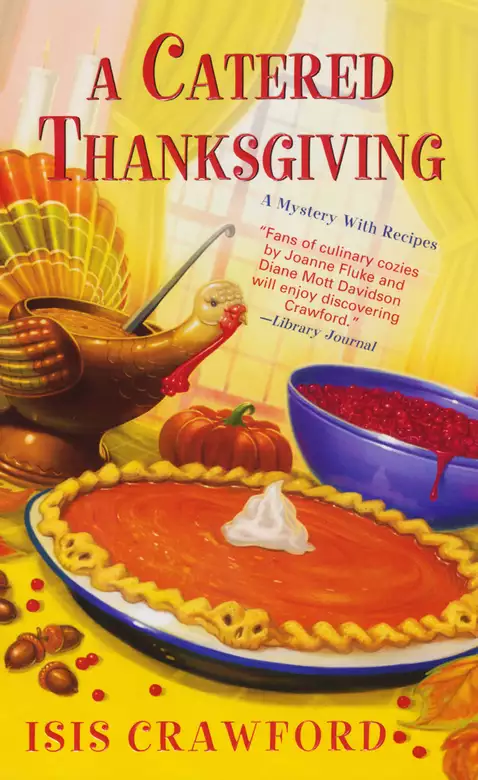

A dysfunctional family holiday turns deadly in this “sprightly” mystery (Publishers Weekly).

Whipping up Thanksgiving dinner can be stressful for anyone, but that goes double for the Field family. Everything has to be perfect, or they risk getting cut out of dominating patriarch Monty’s lucrative will. That’s where sisters Bernie and Libby’s catering company, A Little Taste of Heaven, comes in. Surely with their lumpless mashed potatoes and to-die-for gravy, even the super-dysfunctional Fields can get along for one meal. But no one can dress up disaster when the turkey goes boom right in Monty’s scowling face, sending him to that great dining room in the sky.

With everyone harboring their own cornucopia of secrets, discovering who wanted to carve up Monty won’t be easy. Worse, the Field Mansion is draped under a snowstorm, trapping them with a killer determined to get more than his piece of the pie. Bernie and Libby will have to find out who the culprit is, fast, before the leftovers—and their chances of surviving—run out for good…

Includes tasty recipes!

“Fans of culinary cozies by Joanne Fluke and Diane Mott Davidson will enjoy discovering Crawford.” –Library Journal

Whipping up Thanksgiving dinner can be stressful for anyone, but that goes double for the Field family. Everything has to be perfect, or they risk getting cut out of dominating patriarch Monty’s lucrative will. That’s where sisters Bernie and Libby’s catering company, A Little Taste of Heaven, comes in. Surely with their lumpless mashed potatoes and to-die-for gravy, even the super-dysfunctional Fields can get along for one meal. But no one can dress up disaster when the turkey goes boom right in Monty’s scowling face, sending him to that great dining room in the sky.

With everyone harboring their own cornucopia of secrets, discovering who wanted to carve up Monty won’t be easy. Worse, the Field Mansion is draped under a snowstorm, trapping them with a killer determined to get more than his piece of the pie. Bernie and Libby will have to find out who the culprit is, fast, before the leftovers—and their chances of surviving—run out for good…

Includes tasty recipes!

“Fans of culinary cozies by Joanne Fluke and Diane Mott Davidson will enjoy discovering Crawford.” –Library Journal

Release date: May 26, 2011

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

A Catered Thanksgiving

Isis Crawford

Sean Simmons peeked out of the kitchen door into his daughters’ shop, A Little Taste of Heaven. They were definitely over their occupancy limit. The space between the front door and the counter was jammed with so many people waiting to pick up their orders that a line was beginning to form outside the shop door. The counter people, Googie, Amber, and the new hire, were working at light speed, but they couldn’t keep up with the crush. The day before Thanksgiving was always crazy, but this one, Sean decided, outdid all the others.

Ever since A Little Taste of Heaven had gotten a one-line mention in the New York Times food section lauding their pies, the shop’s phone had been ringing off the hook. Naturally everyone wanted one thing. Pies. You’d think that Westchester didn’t have any other bakeries. His daughters, Libby and Bernie, had been baking around the clock, and they still had 150 orders to finish before the end of the day. They both looked exhausted, but they weren’t going to be able to catch a breather, because they had to cater the Fields’ Thanksgiving dinner the following day. Now, that was a bad idea on several levels, if you asked him, which no one had. It was probably just as well that he was going to his sister’s, Sean reflected as he leaned against the door frame to give himself a little extra support.

That way Bernie and Libby could come home from the Field house and collapse, instead of having to take care of him. Not that they had to—he could always eat a bowl of cereal for dinner—but they would never allow that to happen, especially not on Thanksgiving.

As he looked at the people milling in front of the counter, Sean felt bad that he couldn’t help out. Back in the old days, he’d always pitched in when his wife, Rose, was swamped, but now he was just thankful that he could walk around with a cane, instead of being confined to a wheelchair. Standing for long periods of time was out. And he couldn’t even mix up the fillings or peel the apples. His hands weren’t steady enough for that.

Basically, he was useless for anything other than giving advice and counting and banding the money. God, when he was younger, he could practically leap tall buildings with a single bound, and look at him now. Who would have thought he would have ended up like this?

No, the best thing he could do right now was stay out of his daughters’ way, Sean thought as he took a bite of the pumpkin walnut scone he’d lifted off the baking sheet. The scone was perfect. It had a good crumb and just the right amount of sweetness, which was balanced by the tang of ginger and the seductive taste of Vietnamese cinnamon. He took a sip of his coffee.

His girls were the best bakers he knew. They didn’t cut corners, and they used only the freshest ingredients—just like their mother had. Their pie crusts were made with butter; their pumpkin pie filling was made from sugar pumpkins, which they baked instead of boiled to get maximum flavor; their apple pies were made from a mix of Cortlands, Northern Spys, and Crispins; and they ordered their spices on-line to make sure they weren’t stale.

This year the girls had not only made their own mincemeat, but they’d reintroduced an old holiday favorite—nesserole pie, the recipe for which Libby had found in one of his wife Rose’s recipe books. There was no canned anything in any of their pies. It was an expensive way to do things, but judging from the mob scene outside, people were willing to pay the price—even in economic hard times like these—for quality.

“Your mother would be proud of you,” Sean told Libby and Bernie as they came up behind him.

“She probably would have had something to say about the mincemeat,” Bernie said. “I substituted applejack for brandy.”

Sean laughed and brushed a few scone crumbs off of his shirt. He was dressed for Florida in khaki pants, a white knit shirt, and sneakers. “I’m sure she’d understand, Bernie.”

“I’m not,” Bernie said. Her mother had been a stickler for following recipes to the letter, whereas she tended to take a more free-form approach to baking.

“Well, she wouldn’t be able to argue with the sales figures,” Sean pointed out. It seemed to him as if the shop was going to have its best day ever. “So you must be doing something right.” He looked at his watch. “Marvin will be here to take me to the airport in ten minutes.”

Libby gave Sean a hug. “I wish you weren’t going.”

Sean patted his daughter on the shoulder. “I’ll be back on Saturday.”

Libby bit her lip. “It’ll just feel weird not having you here for Thanksgiving.”

“But you’re catering the Fields’ dinner, anyway,” Sean told her.

“Which we wouldn’t be doing if you were going to be here,” Bernie pointed out.

In her mind, Thanksgiving dinner was sacrosanct. It was a law their mom had enforced, and Libby and Bernie had continued that tradition. Except for this year. This year their dad was going to visit his sister down in Florida. Bernie and Libby had been invited as well, but they’d had to decline since from now until after New Year’s was one of their busiest times of the year and they couldn’t just take off, even though by now both women would have liked nothing more.

Sean sighed. “I couldn’t very well say no, could I?”

Bernie retied her apron strings. “Why not? You haven’t seen Martha in twenty-nine years. What’s another three months?”

Sean gave her “the look.” Which Bernie ignored. As per usual. It had worked with his men. It had worked with the guys he’d arrested. It had never worked with his daughters or his wife.

“Well, it’s true,” Bernie reiterated, putting her hands on her hips. “She calls and you go running.”

“Flying, actually.”

“Not funny, Dad.” Bernie tapped her fingernails against her pant leg. “I just don’t see why we can’t all go down to Orlando ...”

“Sarasota ...”

“Whatever ... in February.”

“Because Martha invited us for now,” Sean said.

“What happened between you two, anyway?” Libby asked before her sister could say anything else. The last thing she wanted was for Bernie and her dad to have a fight before he left. “Why did you guys stop speaking to one another?”

“To be honest, I don’t even remember anymore,” Sean lied. In his opinion, not everything was for sharing.

Bernie favored her dad with an appraising look. “Why do I so not believe that?” she said.

Sean was going to tell her that was what happened when you got old—your memory failed—when Brandon, Bernie’s boyfriend, walked through the door.

“Evening, Mr. S,” he said as he gave Bernie a hug. “All ready for Florida, I see.”

“That I am,” Sean said.

“Don’t worry. Marvin and I will keep an eye on things when you’re gone,” Brandon assured him.

Bernie put her hands on her hips. “We don’t need anyone to keep an eye on anything, thank you very much.”

“Sure you do. Isn’t that right, Mr. S?”

“Absolutely, Brandon,” Sean said. “Appreciate it.”

“Listen,” Bernie began, but she didn’t finish, because at that moment Marvin pulled up in his Volvo.

Brandon grabbed Sean’s suitcase, and they all trooped out to the car. Marvin already had the trunk open. Brandon stowed the suitcase while Sean hugged Bernie and Libby and got in the car. Sean rolled the window down.

“I’m counting on you,” Sean told Brandon.

“Don’t worry about a thing,” Brandon told him.

“I always worry. That’s what I do,” Sean replied as Marvin pulled away from the curb.

Bernie turned to Brandon. “Keep an eye on things?” she said when Marvin had turned the corner. “What was that about?”

Brandon grinned. “It made him feel better, so what’s the harm?”

“I guess you’re right,” Bernie said.

“I’m always right,” Brandon said.

Bernie turned and punched him in the arm.

“That hurt,” Brandon complained.

Now it was Bernie’s turn to grin. “It was supposed to.”

“Poor Marvin,” Libby said, once she and Bernie were back in the shop. She was thinking of Marvin driving with her dad. “We should have taken Dad to the airport. That way we could have spared Marvin an hour and a half of hell.” Her dad was a notorious backseat driver.

“We can’t take Dad.” Bernie indicated the line in front of the counter. “We have one hundred and fifty more orders to finish up. Marvin will survive. He always does. Besides, he likes Dad. Don’t ask me why, but he does. And then if we took Dad, he couldn’t smoke, because we’re not supposed to know that he smokes, and he’s going to want to because he’s nervous about the flight.”

“How could he think we wouldn’t know?” Libby asked. “I can smell it on his clothes, for heaven’s sake.”

Bernie shrugged. She’d thought the same thing when she’d started smoking at eighteen. Her mother, however, had quickly banished that notion.

“Anyway, he shouldn’t be smoking,” Libby said.

“Are you going to tell him not to, sister dear?”

Libby snorted. “No.”

“Well, neither am I.”

The sisters walked back into the kitchen. It was cold and damp outside, and they could feel the late autumn chill through their clothes.

“Forget the smoking thing,” Libby said. “It just feels wrong not to see Dad off.”

Bernie rolled her eyes. “He’s only going to Florida, for heaven’s sake. He’ll be back on Saturday.”

Libby glared at her sister. She was tired and irritable and not in the mood for attitude. “That’s not the point. The point is he needs help.”

Bernie bent over, picked an apple peel off the floor, and put it in the trash. “Marvin will help him.”

“I realize that.” Libby paused to take a piece of chocolate out of the pocket of her flannel shirt, unwrap it, and pop it into her mouth. “But we should be doing it.”

“Maybe, but I think Dad actually prefers Marvin’s help, even though Marvin’s driving makes him crazy,” Bernie observed as she went over to the sink and washed her hands.

“But why?” Libby asked.

Bernie shut off the water and wiped her hands on a paper towel. “Because he doesn’t want us to see him needing help if we don’t have to. It humiliates him.”

“Maybe,” Libby replied. She finished her chocolate and reached in her pocket for another piece. “But what if that storm they’re predicting hits? What if he’s stuck someplace? What then?”

Bernie brushed a stray wisp of hair off her forehead. “He’ll manage. He always does.”

“How can you be sure?”

“I can’t, okay? But he’s going, so let it alone. For heaven’s sake, you sound like Mom,” Bernie pointed out.

Libby bridled herself. “No, I don’t.”

“Yes, you do. You’re a worrier, just like she was.” Bernie went over and gave her sister a quick hug. “It’ll be okay, Libby,” she said. “It’ll all work out. You’ll see.”

“I suppose,” Libby conceded.

“No, definitely,” Bernie reiterated. “If I didn’t think he could make the trip on his own, I never would have let him go. However, we are going to be in trouble if we don’t finish up those pies. Now, that I can guarantee.” By Bernie’s count they had sixty apple, twenty-five apple-cranberry, fifty pumpkin, eight mincemeat, and five nesserole pies to finish up. She flexed her fingers to work the cramps out. “You know,” she said to Libby, “if I never see another pie, it won’t be too soon for me.”

Libby sighed. Her back was aching from bending over the table, and her feet hurt from standing. “You say that every Thanksgiving.”

“But it’s never been like this. We’re going to have to take on an extra baker if it’s like this next year. It’s amazing what one line in the Times can do.”

“Why did they have to mention our pies?” Libby lamented. “Why couldn’t they have mentioned our cheesecakes instead? Those are so much easier to make, not to mention so much more profitable.”

“This is true,” Bernie said.

A while back she had added in their labor costs to the pear-and-almond tart that they made, and the results had been so dismaying that she’d never done it again with similar products.

Libby stifled a yawn. She’d been up since four in the morning, and they weren’t even halfway through the day yet. “I mean, we make a great pumpkin cheesecake, and we’ve only had four orders for those.”

“Maybe next year,” Bernie said, looking at the mound of apples waiting to be prepped. “Yes, why can’t people have something else for dessert?” she mused. “Something like a pumpkin mousse, or a sweet potato torte, or an assortment of cookies and chocolate, or an ice cream cake, or some sort of pudding? If I had time to sleep, I’d dream about pies.”

“Or at least have one pie and a cheesecake,” Libby said, taking up the conversation where she’d left off as she started ladling pumpkin pie filling into the shells she’d made earlier. “All I know is that I’m going to have carpal tunnel syndrome if this keeps up, not to mention a bad back and flat feet.”

“All I know,” Bernie said, “is that I’m going to fall asleep on my feet.”

Libby stopped ladling and went to put the water on to boil so she could make a fresh pot of coffee. “The only saving grace is that the Fields’ dinner is going to be relatively easy to do and then we’ve got Friday off.”

Bernie sighed. “And they’re eating at five, so we can get a little bit of sleep before we have to be there. We could be there even later if we could cook the turkey here,” Bernie observed.

Libby shrugged her shoulders. “What can I say? They wanted the smell of the bird cooking. One of the brothers ...”

“Perceval ...”

“They both look the same to me... .”

“Perceval is the one with the comb-over and the jowls... .”

“Fine. Perceval said, and I quote, ‘The aroma of the roasting bird was one of his favorite parts of the holiday.’ ”

Bernie put down her paring knife. “I wonder if they have a spray with that scent on the market. I bet they do.”

“It’s probably called Holiday,” Libby said, beginning to measure out the coffee. “Or Pilgrim’s Progress.”

“They didn’t eat turkey the first Thanksgiving. That came later.”

“Well, in any case we should dress warm,” Libby said, changing the subject because she wasn’t in the mood to listen to a history lesson at the moment.

“Believe me, I will... .”

“Because I am,” Libby said.

“You always do. I think you support the flannel industry.”

“Ha. Ha. Ha.”

Bernie started on another apple. “I bet it’s fifty degrees in that place.”

Libby laughed. “At the most. Old man Field could afford to heat that place, if he wanted to.”

“I believe the salient words are ‘if he wanted to.’ How can anyone be that cheap?” Bernie asked, having heard Marvin’s story last night at RJ’s about Monty Field not wanting to pay for an extra large casket for his wife.

Libby shrugged. Her mom had been frugal, but certainly nothing like Field. “It’s a sickness.”

“Personally, I think it’s a lack of generosity, which is entirely different.” Bernie peeled two more apples, cored them, sliced them into eighths, and dropped them in a bowl of acidulated water before continuing. “Maybe it doesn’t run in the family. His brothers are spending a fair chunk of change with us,” she continued.

“And they have given us some leeway menu-wise,” Libby pointed out.

“Thank God.” Bernie waved her paring knife in the air to emphasize her point. “But not enough.”

“Thanksgiving menus are always traditional.”

Bernie wrinkled up her nose. “Some traditions should be dispensed with. Like marshmallow and sweet potato casserole. Yuck.”

“Be happy they don’t want something like cocktail franks and grape jelly,” Libby said.

“You’re kidding, right?”

Libby shook her head. “I read that in one of Mom’s old food magazines.”

“That’s beyond disgusting.”

“Maybe it’s not,” Libby said, even though she shared Bernie’s opinion on the matter.

“Why are you trying to pick a fight?” Bernie asked.

“Am not,” Libby replied.

“Are too,” Bernie said, lapsing into her childhood sing-song voice.

“No. I’m not. It’s just that you don’t need to be such a snob,” Libby told her.

“In food, I don’t think that’s such a bad thing, and anyway, you know you are, too,” Bernie retorted. “What did I hear you say about using canned pie fillings yesterday? That they’re an abomination?”

“I said that they were inedible.”

“Same thing,” Bernie pointed out.

“Not really,” Libby said as she got ready to roll out the next batch of pie crusts.

“Of course it is,” Bernie said.

Libby looked at her and stuck out her tongue. Bernie laughed and the moment of tension was over.

“I’m just tired,” Libby explained.

Bernie rubbed her hands again. “Me too.”

The two women went back to work. They could hear the hubbub of the crowd out front over the strains of Simon and Garfunkel coming from Bernie’s iPod. For some reason, these days Libby liked cooking to them. Maybe because she found their music soothing and she had an abiding belief that food always tasted better when you weren’t rushed making it. Food, like people, needed attention to bring out its best.

On the whole, Libby thought that all their customers were being remarkably patient and well behaved. Of course, as the day wore on and people became more stressed, they would probably become less so, especially if what they wanted wasn’t there.

“I wonder how Dad’s meeting with his sister will go,” Libby said after five minutes had gone by.

Bernie looked up from the apple she was peeling. “Mom always said she wasn’t a very nice person. I guess Martha told Dad that Mom was beneath him when he told her they were getting married.”

“How do you know that?”

“I overheard Mom telling Mrs. Feeney that one day. According to her, Dad never spoke to Martha again.”

“Then why did you let me ask him that if you already knew?”

Bernie shrugged. “I just wanted to hear what he was going to say.”

Libby didn’t reply immediately, because she was busy concentrating on putting the pies in the oven. Usually, she put the pie shells in the oven and then filled them to minimize spillage, not the other way around. The fact that she’d reversed the order just showed her how tired she was—not that she needed more proof.

Libby gently closed the oven door. “There must have been other stuff going on between Dad and Martha, as well.”

Bernie shrugged. “I expect there was.”

“Maybe Martha’s mellowed. Dad has.”

“Let’s hope so, for Dad’s sake,” Bernie said.

“She has to have,” Libby said. “Otherwise, she wouldn’t have invited him.”

Bernie looked up. “Possibly. But in my experience people don’t get better as they get older. They get worse.”

It had started snowing in earnest on Thursday by the time Bernie and Libby gathered up the supplies they’d need to cater the Fields’ Thanksgiving dinner. They’d gone to bed as soon as they’d closed the shop at nine o’clock, and slept straight through until seven o’ clock the next morning. They probably would have slept later if one of their customers hadn’t pounded on the shop door and asked if they had any desserts they could sell her for tonight.

Fortunately, Bernie and Libby had an order that hadn’t been picked up yesterday, so Libby had slipped on her robe and trundled downstairs to sell Mrs. Haldapur three pies—two pecan and one juiced apple. Then she’d made a big pot of coffee, toasted some cinnamon bread, added a tub of fresh butter from one of the local dairy farms to the tray, and brought everything upstairs. Bernie had already turned on the TV, and she and her sister sat there watching the Macy’s Day Parade and sipping coffee and eating buttered cinnamon toast for a little while.

“It feels funny not having Dad here,” Libby noted as she ate her third piece of toast.

Bernie looked up from yesterday’s edition of the local paper. “I hope things are going well.”

“Me too,” Libby said. “I mean, he sounded okay when he called. Unless he was putting on an act.”

Bernie closed the paper. “I guess he’ll tell us when he gets home.”

“Even if the visit isn’t going well, he won’t tell us.”

Bernie checked the clock on the wall. It was time to get going. “This is true,” she said as she stood up.

Bernie showered, dried herself off, and slipped into a white long-sleeved T-shirt, followed by a black merino wool turtleneck sweater and her dark green cargo pants. Normally, she wouldn’t wear something like that in the kitchen, as it would be too warm, but she figured, considering the temperature at which Monty Field kept his house, she’d be okay. Then, to be on the safe side, she put a cotton long-sleeved turtleneck in her tote in case she had to change. She finished her outfit with a pair of heavyish green and yellow striped socks under some ankle-length black Dr. Martens. Libby, in turn, put on a white cotton turtleneck shirt, a black cardigan sweater, a pair of black slacks, and a pair of sensible black shoes.

“We’re not serving the food,” Bernie told Libby when she took a look at her outfit.

Libby looked puzzled. “I know that,” she said.

“I wasn’t sure, because you look like a waiter in those clothes.”

Libby shrugged. At this point she was too tired to care. Her clothes were clean. They fit—kinda. And they were unobtrusive.

“You should get some new pants,” her sister added. “Those should be retired. The seat is bagging out.”

“I plan to on Friday,” Libby lied as she closed the door to the flat. She hated shopping.

“And not from a catalog, either. You have to try them on.”

Libby just grunted, annoyed that Bernie had called her out. But she didn’t say anything, because there was no point. She’d tried, but she couldn’t get Bernie to see her point o. . .

Ever since A Little Taste of Heaven had gotten a one-line mention in the New York Times food section lauding their pies, the shop’s phone had been ringing off the hook. Naturally everyone wanted one thing. Pies. You’d think that Westchester didn’t have any other bakeries. His daughters, Libby and Bernie, had been baking around the clock, and they still had 150 orders to finish before the end of the day. They both looked exhausted, but they weren’t going to be able to catch a breather, because they had to cater the Fields’ Thanksgiving dinner the following day. Now, that was a bad idea on several levels, if you asked him, which no one had. It was probably just as well that he was going to his sister’s, Sean reflected as he leaned against the door frame to give himself a little extra support.

That way Bernie and Libby could come home from the Field house and collapse, instead of having to take care of him. Not that they had to—he could always eat a bowl of cereal for dinner—but they would never allow that to happen, especially not on Thanksgiving.

As he looked at the people milling in front of the counter, Sean felt bad that he couldn’t help out. Back in the old days, he’d always pitched in when his wife, Rose, was swamped, but now he was just thankful that he could walk around with a cane, instead of being confined to a wheelchair. Standing for long periods of time was out. And he couldn’t even mix up the fillings or peel the apples. His hands weren’t steady enough for that.

Basically, he was useless for anything other than giving advice and counting and banding the money. God, when he was younger, he could practically leap tall buildings with a single bound, and look at him now. Who would have thought he would have ended up like this?

No, the best thing he could do right now was stay out of his daughters’ way, Sean thought as he took a bite of the pumpkin walnut scone he’d lifted off the baking sheet. The scone was perfect. It had a good crumb and just the right amount of sweetness, which was balanced by the tang of ginger and the seductive taste of Vietnamese cinnamon. He took a sip of his coffee.

His girls were the best bakers he knew. They didn’t cut corners, and they used only the freshest ingredients—just like their mother had. Their pie crusts were made with butter; their pumpkin pie filling was made from sugar pumpkins, which they baked instead of boiled to get maximum flavor; their apple pies were made from a mix of Cortlands, Northern Spys, and Crispins; and they ordered their spices on-line to make sure they weren’t stale.

This year the girls had not only made their own mincemeat, but they’d reintroduced an old holiday favorite—nesserole pie, the recipe for which Libby had found in one of his wife Rose’s recipe books. There was no canned anything in any of their pies. It was an expensive way to do things, but judging from the mob scene outside, people were willing to pay the price—even in economic hard times like these—for quality.

“Your mother would be proud of you,” Sean told Libby and Bernie as they came up behind him.

“She probably would have had something to say about the mincemeat,” Bernie said. “I substituted applejack for brandy.”

Sean laughed and brushed a few scone crumbs off of his shirt. He was dressed for Florida in khaki pants, a white knit shirt, and sneakers. “I’m sure she’d understand, Bernie.”

“I’m not,” Bernie said. Her mother had been a stickler for following recipes to the letter, whereas she tended to take a more free-form approach to baking.

“Well, she wouldn’t be able to argue with the sales figures,” Sean pointed out. It seemed to him as if the shop was going to have its best day ever. “So you must be doing something right.” He looked at his watch. “Marvin will be here to take me to the airport in ten minutes.”

Libby gave Sean a hug. “I wish you weren’t going.”

Sean patted his daughter on the shoulder. “I’ll be back on Saturday.”

Libby bit her lip. “It’ll just feel weird not having you here for Thanksgiving.”

“But you’re catering the Fields’ dinner, anyway,” Sean told her.

“Which we wouldn’t be doing if you were going to be here,” Bernie pointed out.

In her mind, Thanksgiving dinner was sacrosanct. It was a law their mom had enforced, and Libby and Bernie had continued that tradition. Except for this year. This year their dad was going to visit his sister down in Florida. Bernie and Libby had been invited as well, but they’d had to decline since from now until after New Year’s was one of their busiest times of the year and they couldn’t just take off, even though by now both women would have liked nothing more.

Sean sighed. “I couldn’t very well say no, could I?”

Bernie retied her apron strings. “Why not? You haven’t seen Martha in twenty-nine years. What’s another three months?”

Sean gave her “the look.” Which Bernie ignored. As per usual. It had worked with his men. It had worked with the guys he’d arrested. It had never worked with his daughters or his wife.

“Well, it’s true,” Bernie reiterated, putting her hands on her hips. “She calls and you go running.”

“Flying, actually.”

“Not funny, Dad.” Bernie tapped her fingernails against her pant leg. “I just don’t see why we can’t all go down to Orlando ...”

“Sarasota ...”

“Whatever ... in February.”

“Because Martha invited us for now,” Sean said.

“What happened between you two, anyway?” Libby asked before her sister could say anything else. The last thing she wanted was for Bernie and her dad to have a fight before he left. “Why did you guys stop speaking to one another?”

“To be honest, I don’t even remember anymore,” Sean lied. In his opinion, not everything was for sharing.

Bernie favored her dad with an appraising look. “Why do I so not believe that?” she said.

Sean was going to tell her that was what happened when you got old—your memory failed—when Brandon, Bernie’s boyfriend, walked through the door.

“Evening, Mr. S,” he said as he gave Bernie a hug. “All ready for Florida, I see.”

“That I am,” Sean said.

“Don’t worry. Marvin and I will keep an eye on things when you’re gone,” Brandon assured him.

Bernie put her hands on her hips. “We don’t need anyone to keep an eye on anything, thank you very much.”

“Sure you do. Isn’t that right, Mr. S?”

“Absolutely, Brandon,” Sean said. “Appreciate it.”

“Listen,” Bernie began, but she didn’t finish, because at that moment Marvin pulled up in his Volvo.

Brandon grabbed Sean’s suitcase, and they all trooped out to the car. Marvin already had the trunk open. Brandon stowed the suitcase while Sean hugged Bernie and Libby and got in the car. Sean rolled the window down.

“I’m counting on you,” Sean told Brandon.

“Don’t worry about a thing,” Brandon told him.

“I always worry. That’s what I do,” Sean replied as Marvin pulled away from the curb.

Bernie turned to Brandon. “Keep an eye on things?” she said when Marvin had turned the corner. “What was that about?”

Brandon grinned. “It made him feel better, so what’s the harm?”

“I guess you’re right,” Bernie said.

“I’m always right,” Brandon said.

Bernie turned and punched him in the arm.

“That hurt,” Brandon complained.

Now it was Bernie’s turn to grin. “It was supposed to.”

“Poor Marvin,” Libby said, once she and Bernie were back in the shop. She was thinking of Marvin driving with her dad. “We should have taken Dad to the airport. That way we could have spared Marvin an hour and a half of hell.” Her dad was a notorious backseat driver.

“We can’t take Dad.” Bernie indicated the line in front of the counter. “We have one hundred and fifty more orders to finish up. Marvin will survive. He always does. Besides, he likes Dad. Don’t ask me why, but he does. And then if we took Dad, he couldn’t smoke, because we’re not supposed to know that he smokes, and he’s going to want to because he’s nervous about the flight.”

“How could he think we wouldn’t know?” Libby asked. “I can smell it on his clothes, for heaven’s sake.”

Bernie shrugged. She’d thought the same thing when she’d started smoking at eighteen. Her mother, however, had quickly banished that notion.

“Anyway, he shouldn’t be smoking,” Libby said.

“Are you going to tell him not to, sister dear?”

Libby snorted. “No.”

“Well, neither am I.”

The sisters walked back into the kitchen. It was cold and damp outside, and they could feel the late autumn chill through their clothes.

“Forget the smoking thing,” Libby said. “It just feels wrong not to see Dad off.”

Bernie rolled her eyes. “He’s only going to Florida, for heaven’s sake. He’ll be back on Saturday.”

Libby glared at her sister. She was tired and irritable and not in the mood for attitude. “That’s not the point. The point is he needs help.”

Bernie bent over, picked an apple peel off the floor, and put it in the trash. “Marvin will help him.”

“I realize that.” Libby paused to take a piece of chocolate out of the pocket of her flannel shirt, unwrap it, and pop it into her mouth. “But we should be doing it.”

“Maybe, but I think Dad actually prefers Marvin’s help, even though Marvin’s driving makes him crazy,” Bernie observed as she went over to the sink and washed her hands.

“But why?” Libby asked.

Bernie shut off the water and wiped her hands on a paper towel. “Because he doesn’t want us to see him needing help if we don’t have to. It humiliates him.”

“Maybe,” Libby replied. She finished her chocolate and reached in her pocket for another piece. “But what if that storm they’re predicting hits? What if he’s stuck someplace? What then?”

Bernie brushed a stray wisp of hair off her forehead. “He’ll manage. He always does.”

“How can you be sure?”

“I can’t, okay? But he’s going, so let it alone. For heaven’s sake, you sound like Mom,” Bernie pointed out.

Libby bridled herself. “No, I don’t.”

“Yes, you do. You’re a worrier, just like she was.” Bernie went over and gave her sister a quick hug. “It’ll be okay, Libby,” she said. “It’ll all work out. You’ll see.”

“I suppose,” Libby conceded.

“No, definitely,” Bernie reiterated. “If I didn’t think he could make the trip on his own, I never would have let him go. However, we are going to be in trouble if we don’t finish up those pies. Now, that I can guarantee.” By Bernie’s count they had sixty apple, twenty-five apple-cranberry, fifty pumpkin, eight mincemeat, and five nesserole pies to finish up. She flexed her fingers to work the cramps out. “You know,” she said to Libby, “if I never see another pie, it won’t be too soon for me.”

Libby sighed. Her back was aching from bending over the table, and her feet hurt from standing. “You say that every Thanksgiving.”

“But it’s never been like this. We’re going to have to take on an extra baker if it’s like this next year. It’s amazing what one line in the Times can do.”

“Why did they have to mention our pies?” Libby lamented. “Why couldn’t they have mentioned our cheesecakes instead? Those are so much easier to make, not to mention so much more profitable.”

“This is true,” Bernie said.

A while back she had added in their labor costs to the pear-and-almond tart that they made, and the results had been so dismaying that she’d never done it again with similar products.

Libby stifled a yawn. She’d been up since four in the morning, and they weren’t even halfway through the day yet. “I mean, we make a great pumpkin cheesecake, and we’ve only had four orders for those.”

“Maybe next year,” Bernie said, looking at the mound of apples waiting to be prepped. “Yes, why can’t people have something else for dessert?” she mused. “Something like a pumpkin mousse, or a sweet potato torte, or an assortment of cookies and chocolate, or an ice cream cake, or some sort of pudding? If I had time to sleep, I’d dream about pies.”

“Or at least have one pie and a cheesecake,” Libby said, taking up the conversation where she’d left off as she started ladling pumpkin pie filling into the shells she’d made earlier. “All I know is that I’m going to have carpal tunnel syndrome if this keeps up, not to mention a bad back and flat feet.”

“All I know,” Bernie said, “is that I’m going to fall asleep on my feet.”

Libby stopped ladling and went to put the water on to boil so she could make a fresh pot of coffee. “The only saving grace is that the Fields’ dinner is going to be relatively easy to do and then we’ve got Friday off.”

Bernie sighed. “And they’re eating at five, so we can get a little bit of sleep before we have to be there. We could be there even later if we could cook the turkey here,” Bernie observed.

Libby shrugged her shoulders. “What can I say? They wanted the smell of the bird cooking. One of the brothers ...”

“Perceval ...”

“They both look the same to me... .”

“Perceval is the one with the comb-over and the jowls... .”

“Fine. Perceval said, and I quote, ‘The aroma of the roasting bird was one of his favorite parts of the holiday.’ ”

Bernie put down her paring knife. “I wonder if they have a spray with that scent on the market. I bet they do.”

“It’s probably called Holiday,” Libby said, beginning to measure out the coffee. “Or Pilgrim’s Progress.”

“They didn’t eat turkey the first Thanksgiving. That came later.”

“Well, in any case we should dress warm,” Libby said, changing the subject because she wasn’t in the mood to listen to a history lesson at the moment.

“Believe me, I will... .”

“Because I am,” Libby said.

“You always do. I think you support the flannel industry.”

“Ha. Ha. Ha.”

Bernie started on another apple. “I bet it’s fifty degrees in that place.”

Libby laughed. “At the most. Old man Field could afford to heat that place, if he wanted to.”

“I believe the salient words are ‘if he wanted to.’ How can anyone be that cheap?” Bernie asked, having heard Marvin’s story last night at RJ’s about Monty Field not wanting to pay for an extra large casket for his wife.

Libby shrugged. Her mom had been frugal, but certainly nothing like Field. “It’s a sickness.”

“Personally, I think it’s a lack of generosity, which is entirely different.” Bernie peeled two more apples, cored them, sliced them into eighths, and dropped them in a bowl of acidulated water before continuing. “Maybe it doesn’t run in the family. His brothers are spending a fair chunk of change with us,” she continued.

“And they have given us some leeway menu-wise,” Libby pointed out.

“Thank God.” Bernie waved her paring knife in the air to emphasize her point. “But not enough.”

“Thanksgiving menus are always traditional.”

Bernie wrinkled up her nose. “Some traditions should be dispensed with. Like marshmallow and sweet potato casserole. Yuck.”

“Be happy they don’t want something like cocktail franks and grape jelly,” Libby said.

“You’re kidding, right?”

Libby shook her head. “I read that in one of Mom’s old food magazines.”

“That’s beyond disgusting.”

“Maybe it’s not,” Libby said, even though she shared Bernie’s opinion on the matter.

“Why are you trying to pick a fight?” Bernie asked.

“Am not,” Libby replied.

“Are too,” Bernie said, lapsing into her childhood sing-song voice.

“No. I’m not. It’s just that you don’t need to be such a snob,” Libby told her.

“In food, I don’t think that’s such a bad thing, and anyway, you know you are, too,” Bernie retorted. “What did I hear you say about using canned pie fillings yesterday? That they’re an abomination?”

“I said that they were inedible.”

“Same thing,” Bernie pointed out.

“Not really,” Libby said as she got ready to roll out the next batch of pie crusts.

“Of course it is,” Bernie said.

Libby looked at her and stuck out her tongue. Bernie laughed and the moment of tension was over.

“I’m just tired,” Libby explained.

Bernie rubbed her hands again. “Me too.”

The two women went back to work. They could hear the hubbub of the crowd out front over the strains of Simon and Garfunkel coming from Bernie’s iPod. For some reason, these days Libby liked cooking to them. Maybe because she found their music soothing and she had an abiding belief that food always tasted better when you weren’t rushed making it. Food, like people, needed attention to bring out its best.

On the whole, Libby thought that all their customers were being remarkably patient and well behaved. Of course, as the day wore on and people became more stressed, they would probably become less so, especially if what they wanted wasn’t there.

“I wonder how Dad’s meeting with his sister will go,” Libby said after five minutes had gone by.

Bernie looked up from the apple she was peeling. “Mom always said she wasn’t a very nice person. I guess Martha told Dad that Mom was beneath him when he told her they were getting married.”

“How do you know that?”

“I overheard Mom telling Mrs. Feeney that one day. According to her, Dad never spoke to Martha again.”

“Then why did you let me ask him that if you already knew?”

Bernie shrugged. “I just wanted to hear what he was going to say.”

Libby didn’t reply immediately, because she was busy concentrating on putting the pies in the oven. Usually, she put the pie shells in the oven and then filled them to minimize spillage, not the other way around. The fact that she’d reversed the order just showed her how tired she was—not that she needed more proof.

Libby gently closed the oven door. “There must have been other stuff going on between Dad and Martha, as well.”

Bernie shrugged. “I expect there was.”

“Maybe Martha’s mellowed. Dad has.”

“Let’s hope so, for Dad’s sake,” Bernie said.

“She has to have,” Libby said. “Otherwise, she wouldn’t have invited him.”

Bernie looked up. “Possibly. But in my experience people don’t get better as they get older. They get worse.”

It had started snowing in earnest on Thursday by the time Bernie and Libby gathered up the supplies they’d need to cater the Fields’ Thanksgiving dinner. They’d gone to bed as soon as they’d closed the shop at nine o’clock, and slept straight through until seven o’ clock the next morning. They probably would have slept later if one of their customers hadn’t pounded on the shop door and asked if they had any desserts they could sell her for tonight.

Fortunately, Bernie and Libby had an order that hadn’t been picked up yesterday, so Libby had slipped on her robe and trundled downstairs to sell Mrs. Haldapur three pies—two pecan and one juiced apple. Then she’d made a big pot of coffee, toasted some cinnamon bread, added a tub of fresh butter from one of the local dairy farms to the tray, and brought everything upstairs. Bernie had already turned on the TV, and she and her sister sat there watching the Macy’s Day Parade and sipping coffee and eating buttered cinnamon toast for a little while.

“It feels funny not having Dad here,” Libby noted as she ate her third piece of toast.

Bernie looked up from yesterday’s edition of the local paper. “I hope things are going well.”

“Me too,” Libby said. “I mean, he sounded okay when he called. Unless he was putting on an act.”

Bernie closed the paper. “I guess he’ll tell us when he gets home.”

“Even if the visit isn’t going well, he won’t tell us.”

Bernie checked the clock on the wall. It was time to get going. “This is true,” she said as she stood up.

Bernie showered, dried herself off, and slipped into a white long-sleeved T-shirt, followed by a black merino wool turtleneck sweater and her dark green cargo pants. Normally, she wouldn’t wear something like that in the kitchen, as it would be too warm, but she figured, considering the temperature at which Monty Field kept his house, she’d be okay. Then, to be on the safe side, she put a cotton long-sleeved turtleneck in her tote in case she had to change. She finished her outfit with a pair of heavyish green and yellow striped socks under some ankle-length black Dr. Martens. Libby, in turn, put on a white cotton turtleneck shirt, a black cardigan sweater, a pair of black slacks, and a pair of sensible black shoes.

“We’re not serving the food,” Bernie told Libby when she took a look at her outfit.

Libby looked puzzled. “I know that,” she said.

“I wasn’t sure, because you look like a waiter in those clothes.”

Libby shrugged. At this point she was too tired to care. Her clothes were clean. They fit—kinda. And they were unobtrusive.

“You should get some new pants,” her sister added. “Those should be retired. The seat is bagging out.”

“I plan to on Friday,” Libby lied as she closed the door to the flat. She hated shopping.

“And not from a catalog, either. You have to try them on.”

Libby just grunted, annoyed that Bernie had called her out. But she didn’t say anything, because there was no point. She’d tried, but she couldn’t get Bernie to see her point o. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

A Catered Thanksgiving

Isis Crawford

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved