- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

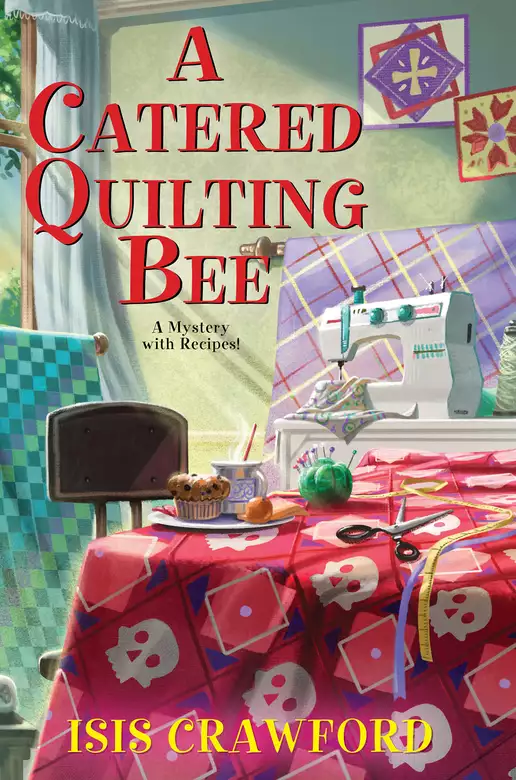

Sisters and caterers Bernie and Libby Simmons, owners of A Little Taste of Heaven, return for another culinary cozy with catering, dogs, and murder.

Quilts, quiet, and delicious food. That’s exactly what Bernie and Libby expect as they build the menu for the Longely Sip and Sew Quilting Circle’s first-ever exhibition hosted at the local library. The eclectic ladies of the group couldn’t appear more harmlessly wholesome if they tried, especially mild-mannered kindergarten teacher Cecilia Larson, who hired A Little of Taste of Heaven to cater the event. So it’s a complete shock when disturbing news drops about member Ellen Fisher, found hanging from a plant hook in her otherwise pristine sewing room . . .

All are very quick to deem the tragic death a suicide. All except for Cecilia. She believes something else happened to her best friend—who was busy adding the finishing stitches on her greatest work yet in hopes of displaying it at the exhibition—and looks to Bernie and Libby to expose the truth . . . and the killer. As Ellen’s patchy past comes into focus along with a mysterious connection to a missing seven-hundred-year-old quilt fragment, can the sisters unravel the victim’s final thread before another turns up dead?

Includes Original Recipes for You to Try!

Release date: February 20, 2024

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Catered Quilting Bee

Isis Crawford

She’d pictured a heavyset middle-aged lady wearing a cardigan sweater, a plaid skirt, and sneakers instead of a cool-looking, willowy blonde with perfect eyebrows, bright purple eye shadow, leggings, and a crop top that revealed toned abs decorated with a kaleidoscope of tattoos. In Bernie’s mind, people who looked like Cecilia didn’t teach kindergarten. Or quilt. Or hang out at libraries. They hung out around Rodeo Drive and lunched at the country club.

Cecilia brightened when she saw the sisters. “This way,” she mouthed, beckoning for Bernie and Libby to follow her.

Libby nodded. She realized it had been a while since she’d been at the library. Built ten years ago, the large, one-story brick building had replaced the cozy ninety-year-old Queen Anne on Main Street. But what the new building lacked in charm it made up for with its floor-to-ceiling windows, cheerful interior, comfy chairs for reading, and plentiful parking. This early March afternoon, it was filled with an after-school crowd: mothers and toddlers paging through picture books in the children’s section, elementary school kids doing class projects, gaggles of teenagers hunched over their computers, and adults checking out the latest bestseller or browsing through the library’s collection of newspapers.

Bernie and Libby stopped to say hello to several of their customers from A Little Taste of Heaven while they wended their way through the reference section and past the children’s corner to the back room where the library held classes and hosted art exhibitions of one kind or another. Which was why they were there now. Next month’s show featured quilts made by the Longely Sip and Sew Quilting Society, and she and her sister had been hired to cater the event.

“I take it this is where the reception is going to be?” Bernie asked Cecilia as she glanced around the large room. She and Libby always liked to see where they’d be setting up before the actual event. That way they could catch any problems before they occurred.

Cecilia nodded. “This is the place,” she said, gesturing to the pale yellow walls, then indicating the two long black folding tables in the middle of room. “What do you think? Do we need another table?”

Bernie shook her head. “I think two will be enough. One for the food and the other for the drinks and the plates and so on. Are we doing paper or the real stuff?”

“What’s the difference?” Cecilia asked.

“Price,” Libby answered.

“Then let’s do paper,” Cecilia said. “How about tablecloths?” Cecilia continued. “Will you supply them? Are they included in the price?”

“Yes, and absolutely,” Libby replied, her eyes drawn to the other table. “Maybe something in a deeper shade of yellow to offset the patterns and provide a feeling of unity.”

“Perfect,” Cecilia said, following Libby’s glance. The second table was piled high with square and rectangular quilts. Some were big, some were small, but together they formed a riot of colors and patterns. “I’m trying to figure out how I’m going to hang them,” she informed Libby.

“Looks like a big job,” Libby observed.

Cecilia rolled her eyes. “You can say that again. Had I only known.” She shook her head. “Everyone is so touchy. So do or die. God forbid anyone should feel slighted about their place in the display. Really. You’d think we were talking about an exhibition at the Met.”

Libby rubbed her chin with her knuckle. “My mom had quilts,” she remarked.

“What happened to them?” Cecilia asked, noting the tense.

Bernie answered the question. “I’m not sure,” she lied, not wanting to say her dad had donated them to Goodwill after her mom had died. Somehow, that seemed disrespectful. But in truth, her dad had never liked them, and neither had she. “The quilts on the table don’t look like the ones my mother had,” she said instead. Her mom’s had been linear and subdued, all angles and dark-colored pieces of fabric. They had always reminded her of pioneer houses with smoke-blackened mantels, crying babies, and pots of stew cooking over the fire.

Cecilia laughed. “Well, the quilts on the table are modern. Or, I should say, modern designs. Free form. I bet your mom had log cabins and double stars.” And she went on to explain about the history of quilting after seeing the blank looks on Bernie’s and Libby’s faces. “Historians think quilting might have started in ancient Egypt. Maybe even earlier. People have quilted throughout the ages, sometimes to make warm vests and blankets, sometimes to make art, sometimes to leave messages for one another, like the slaves did in the South. Did you know that the oldest example of a quilt is a remnant of a bedcovering from the thirteen hundreds? The thirteen hundreds! I ask you, how fantastic is that?”

Bernie wrinkled her forehead. “Oh yeah. That was stolen from the Met, right? The guard had a heart attack?” The story of the heist had been part of a documentary she’d seen recently on Netflix.

“Right,” Cecilia said. She frowned. “I don’t think the authorities ever recovered the fragment. Such a shame.”

“I wonder what happened to it,” Bernie mused.

“It’s probably sitting in some rich collector’s basement somewhere,” Libby guessed.

“Probably,” Bernie agreed. “That kind of stuff would be hard to sell on the open market.” She shook her head. “Fabric from the thirteen hundreds. Wow. They sure don’t make material like they did back then,” she observed.

Cecilia laughed. “No, they sure don’t,” she said. “You’re lucky these days if a T-shirt lasts a year. Nylon has been the death of fabric,” she proclaimed. Then she laughed at herself. “Listen to me making pronouncements like an expert. It’s all so fascinating, though. I mean, think about it. Who invented material? How did our ancestors go from wearing animal skins and palm leaves and coconut shells to wearing clothes made from cloth?”

“I never thought of it that way,” Libby murmured.

“Most people don’t,” Cecilia replied. Her expression turned thoughtful. “In one sense, quilting saved my life,” she said. “It gave me a community, a reason to be.” Then she gave an embarrassed little grin and apologized. “Sorry about oversharing.” She shook her head for the second time and waved her hand in front of her face, banishing the sentence she’d just uttered to the netherworld. “But that’s a story for another time,” she told the sisters, squaring her shoulders and setting her jaw. “Let’s talk about the menu, shall we? I have some ideas.”

Oh no, Bernie thought, remembering some of their other clients’ brainstorms, but as it turned out, Cecilia’s ideas weren’t bad. Not inspired, but not awful, either. Her ideas centered around a fifties Americana retro menu featuring Jell-O molds, deviled eggs, pigs in a blanket, a variety of mini quiches and spanakopita, as well as a vegetable platter designed like a loom—although Bernie had no idea how they would accomplish that—and a cookie platter.

“And, of course, we’ll want wine and hard cider, as well,” Cecilia continued. “After all, we don’t call ourselves the Longely Sip and Sew Quilting Society for nothing. Have to live up to our rep,” she added brightly.

Bernie and Libby both smiled politely.

“And the cake,” Libby prompted. “Have you decided what you want yet?”

“Ah, yes, the cake,” Cecilia repeated. She was about to say she was thinking about something springlike—maybe an orange sheet cake with vanilla frosting decorated with flowers, either nasturtiums or Johnny-jump-ups—when Gail Gibson burst into the room.

Libby recognized her from their shop, A Little Taste of Heaven. She had come in once or twice a month for the past four years to get a dozen croissants, the featured fruit crostata of the day, and two portions of the shop’s famous fried mustard chicken. A fireplug of a woman with short gray hair and an affinity for pink ruffled shirts and denim pencil skirts, she radiated a take-charge vibe. But today that vibe was gone. She looked panicked and on the verge of tears.

“Why don’t you pick up your phone?” she demanded of Cecilia from the doorway. “I’ve been trying to call you.”

Cecilia made a face. “Sorry. I guess I forgot to turn the ringer back on after work.”

“Next time, don’t forget.”

“I said I was sorry, Gail,” Cecilia snapped. “You know, you’re not really one to talk.”

Gail opened her mouth to retort in kind, thought better of it, and closed it. Instead, she said, “Thank God I remembered that you were supposed to be here.”

Cecilia’s expression changed from annoyance to concern. “Why? What’s the matter?” Cecilia asked Gail. “You know, you don’t look so hot,” she commented after noting the tear in Gail’s stocking and her smeared eye makeup.

“I don’t feel so hot.” Gail swallowed and bit her lip. “She’s dead. I can’t believe it. I just can’t.”

“Who’s dead?” Cecilia asked as Libby got a folding chair from the corner and told Gail to sit down.

“Selene called and told me,” Gail said, ignoring Libby’s request.

“Selene White?” Cecilia asked.

Gail nodded and started to cry. “She’s hysterical. I told her we’d be there. We have to go. I already called Judy. She said she’d get there as fast as she could.”

“Who is dead? Where do we have to go?” Cecilia asked, looking alarmed. “What are you talking about?”

Gail hiccupped. She took a deep breath. “Ellen is dead.”

“Our Ellen?” Cecilia asked incredulously.

“Yes, our Ellen,” Gail replied.

Cecilia’s eyes widened. “Ellen Fisher?”

Gail nodded.

“You’re kidding me, right? I just got a text from her a little while ago,” Cecilia said.

“I don’t know what to tell you,” Gail replied.

Cecilia put her hand to her mouth. “Oh my God. That’s terrible. What happened? Was she in a car accident?” Ellen was a terrible driver. “Did she have a heart attack?”

Gail shook her head. “Ellen killed herself. Selene said she found her hanging from a plant hook in her sewing room. She used her binding.”

Cecilia blinked. “I don’t believe it. We talked this morning. She wanted to know if I had seen the latest edition of Quilt Today.”

“It’s true,” Gail said, and she started to sob. Then her phone rang. She wiped her eyes with the back of her hand and reached in her bag to get it. “Oh my God,” she exclaimed when she saw the caller ID. “I forgot. I’m supposed to be teaching Anthro 101 now. I have to call the departmental secretary and tell them to cancel the class.”

“I’d go, but I have an appointment I have to show up for,” Cecilia said. “I’m sorry.”

Gail sniffed. “It’s okay. I’ll go after I make this call.”

“Are you sure you can drive, Gail?” Cecilia said. “Your hands are shaking.”

Gail looked down at them. “I guess they are. But someone has to. Selene needs us.”

Bernie and Libby exchanged looks. Libby gave an imperceptible nod.

“It’s okay. We’ll go,” Bernie told Cecilia and Gail. “Call Selene and tell her we’re on our way.”

Gail reached over and clasped Bernie’s hand. “Thank you. Thank you so much. I don’t think I could bear to see . . .” She swallowed. “Well, you know.” Then she collapsed into the chair Libby had pulled out for her.

As the sisters left, they could hear Cecilia saying, “I don’t understand. I don’t understand at all. When I talked to Ellen this morning, it sounded as if everything was fine. We were talking about restitching some of the binding. I can’t believe she hanged herself with it.”

Two police cars, a small fire engine, and an ambulance were parked in front of Ellen Fisher’s house when Bernie and Libby arrived. Three neighbors were standing on the sidewalk, talking in low tones, while a small group of first responders were standing off to the side, chatting with each other. Bernie parked the van across the street from the first responders’ vehicles, and she and Libby walked over.

As they approached, a flock of sparrows rose from the bird feeder and landed on the lilac bush by the wooden fence, while a robin pecked at the birdseed scattered on the ground. A squirrel chittered at Bernie from the bottom of the white birch tree in the front yard.

Ellen Fisher’s house didn’t have much curb appeal, but then, Bernie reflected, neither did the other houses on the block. An undistinguished two-story gray colonial with black shutters, a matching black door, and scraggly arborvitae planted around its foundation, it was the kind of place you’d never give a second glance to when you drove by.

“Look, it’s the Simmons sisters,” a policeman yelled out as Libby and Bernie started up the path to Ellen Fisher’s house. “Come to save the day with chocolate cupcakes?”

“More like chocolate chip macadamia cookies,” Bernie said, showing the officer the one she’d been saving to eat later.

The policeman laughed. “For me?” he asked.

Bernie pointed to the woman she assumed to be Selene. “No, for her, but stop by the shop and tell my countergirl, Amber, I said to give you a couple.”

“I might do that,” the policeman replied as Bernie and Libby approached Selene. She was half standing, half leaning against the large white birch next to Ellen Fisher’s house.

If Gail Gibson was a fireplug, then Selene White was a stork—tall and thin, with a long nose. The pair of them reminded Bernie of Mutt and Jeff, her dad’s favorite cartoon characters. She looked lost in her business suit and high heels, Bernie reflected. As if she’d shrunk.

“Gail sent us,” Libby said to Selene when they got closer.

Bernie held out the cookie. “Here. Have it.”

Selene shook her head. “Thanks, but I’m not hungry.”

“Eat it,” Bernie said. “It’ll help you from going into shock.”

Selene took the cookie.

“How are you doing?” Libby asked as she watched Selene take a nibble.

“Terrible,” Selene said, straightening up and hugging herself. “Really awful.”

“Of course you are,” Libby murmured.

Selene swallowed. “I still can’t believe it. I thought it was a really bad joke at first. I was going to tell Ellen off when she opened the door. Something along the lines of ‘That’s not funny, not funny at all.’” She stifled a sob. “Talk about irony.” Selene took a deep breath and let it out. “She . . .”

“You mean Ellen?” Libby asked.

Selene nodded. “Said she wanted my advice on the binding for the quilt she was finishing. She asked me to drop over.” Selene bit her lip. “You think you know what’s going to happen when you get up in the morning, but you don’t. Not really.”

Selene ran a finger down the trunk of the birch tree. Libby and Bernie waited for her to continue. A moment later, she did. “When I got here, I knocked on the door, because the bell is broken.” She pointed to a sign taped on Ellen Fisher’s front door that said KNOCK LOUDLY. The word knock was underlined three times. “It’s been broken for a year now. Ellen kept saying she was going to get it fixed, but she never did, and now she never will.” Selene sniffed. “When Ellen didn’t answer, I knocked again. I figured maybe she was taking a shower or doing the laundry or something like that, you know?”

Both Libby and Bernie nodded to show that they understood.

Selene continued with her narrative. “Then I knocked a third time, and when she didn’t answer, I went around to the back. I thought maybe she was gardening and she didn’t hear me. She liked to listen to music when she did.” Selene stopped talking for a moment and closed her eyes. A minute later, she opened them. “And then the cat meowed.”

“The cat?” Libby asked.

“Miss M. She was sitting in the window. So, I turned. At first, I saw this bunch of orange flowers. And then I saw . . .” Selene stopped talking again.

“It’s okay,” Libby said. “You don’t have to tell us.”

Selene held up her hands. “No. No. I want to. I have to.” She cleared her throat. “That’s when I saw . . . Ellen . . . I thought it was a joke. I really did. Oh. I already said that! I’m sorry.”

“It’s fine. Don’t worry about it,” Bernie reassured her.

Selene thanked her. “There were orange flowers in a vase on the sewing table. Ellen really liked flowers. She always had a vaseful. For some reason, I remember thinking it was nice that they were the last thing Ellen had smelled. Funny how your mind works.” Selene shook her head. “If the cat hadn’t meowed, I wouldn’t have turned, and I wouldn’t have seen . . . her.”

Selene stifled a sob and pulled on her bangs. “I thought everything was fine. Well, not exactly fine. I knew Ellen was having . . . issues. We talked, but I thought they were getting resolved.” Selene blinked. “I should have seen it.”

Libby reached over and patted Selene’s shoulder. “You couldn’t have known.”

“Yes, I could have,” Selene said, her voice turning fierce. “More to the point, I should have. I’m a psychologist, for heaven’s sake. Maybe it’s time for me to hang up my shingle and become a greeter at Walmart.” Suddenly Selene stiffened. She swayed from side to side and closed her eyes. “Oh my God, what’s happening to me? Everything is spinning.”

“I think you’re going into shock,” Libby said as she took hold of Selene’s arm, guided her to Ellen’s front porch steps, and helped her sit down on the top one while Bernie went to get an EMT.

“I’m fine,” Selene was saying to Libby when Bernie returned. She was still protesting to the EMT that she was okay when Bernie and Libby left her and went around to the back. Through the open door, they could see the morgue attendants cutting Ellen Fisher’s body down. A moment later, their dad’s friend Clyde came out the door. He was a senior detective on the Longely police force.

“What are you two doing here?” he asked when he spotted them.

Bernie replied, “Lending moral support to the woman who found the body.”

“Selene White?” Clyde asked.

Bernie and Libby nodded.

“She’s gonna need it,” Clyde said.

Libby nodded. “She seems pretty shaken up.”

“Wouldn’t you be? That’s not a nice sight to be greeted with,” Clyde observed. He was a big guy at six feet, four inches and 260 pounds, but recently age—he was nearing sixty-five—had lent a slight stoop to his shoulders.

“No, definitely not,” Bernie said. “It would be hard to unsee.”

“For sure,” Clyde replied. “Did you two know Ellen Fisher?”

Bernie and Libby both shook their heads.

“She never came into the shop,” Libby told him. “Do you?”

“She taught one of my daughters,” Clyde said. “How about Selene White?”

“She isn’t one of our customers, either,” Bernie told him.

Clyde nodded to show he was listening. Then he said, “According to the statement she made, she came by to give Ellen Fisher an opinion on the binding for her quilt.”

“That’s what she told us, too,” Bernie confirmed.

“It’s nice when things align,” Clyde observed.

“Trust but verify,” Bernie said, repeating what her dad, who had served as the Longely chief of police before he’d been forced out, always said.

Clyde grinned. “An oldie but a goody.”

Clyde, Bernie, and Libby were quiet for a moment as they watched the attendants load Ellen Fisher’s body into the ambulance parked by the back door.

Clyde shook his head. “Such a waste. She was so good with my daughter,” he reflected. “Miranda could hardly wait to get to school in the mornings. She used to cry when the weekends came because she couldn’t go to class. And she was really nice to my wife. Helped her with a couple of quilts she was making.” For a moment, he watched a pair of blue jays pecking at something on Ellen Fisher’s lawn; then he continued with what he’d been saying. “You know,” he said, “I can understand why you would kill yourself if you had something like ALS, but when you’re healthy and relatively young . . .” He hitched his pants up. “I don’t get it.”

“You think she killed herself, then?” Bernie asked.

“That’s what the evidence suggests,” Clyde responded. “There were no signs of a struggle, no signs that Ellen Fisher had been involved in an altercation of any kind. According to the responding officer’s account, Selene said she knocked, but when no one answered, she went around to the back, figuring maybe Ellen Fisher was in the backyard. She wasn’t. Evidently, Selene was just leaving—she thought maybe she’d gotten the time wrong—when she heard Ellen’s cat, at which point she turned and looked through the rear window. That’s when she saw Ellen hanging from a hook in the sewing room ceiling and called nine-one-one.”

“Did she try to get in after she called you guys?” Libby asked.

Clyde nodded. “According to the statement she gave to Officer Shaw, she tried the back door, but it was locked, at which point she looked for the key that Ellen usually kept underneath that ceramic turtle.” Clyde pointed to the sculpture by Ellen Fisher’s back door. “But the key wasn’t there.”

“So, someone took it?” Libby asked.

“Maybe,” Clyde responded, “but Selene said Ellen Fisher was always forgetting her key, using her spare, and forgetting to put it back.”

“Was anything taken from the house?” Bernie asked Clyde.

Clyde thought about what he’d seen on the first floor. There had been no signs of a struggle. Everything had looked in order. The living-room and dining-room furnishings were like the house—neat and unremarkable. The sofa and the chairs in the living room were gently worn, the coffee table was piled high with newspapers and magazines, and there was a cat tree near the fireplace and several random cat toys on the floor.

One half of the Queen Anne cherrywood table in the dining room was covered with neatly folded pieces of fabric of various sizes and patterns, while the other half of the table hosted packets of colored construction paper, boxes of crayons, and small white cardboard boxes.

“It doesn’t look that way,” he told Libby. “But considering we don’t know what was in there to begin with, your guess is as good as mine.”

“Fair enough,” Libby said.

Bernie looked at her watch. It was time to get back to the shop. They had things to do. They left after they’d checked on Selene to make sure she was doing okay.

“So depressing,” Libby said as she stared out the window at the dreary March landscape.

“The landscape or Ellen Fisher?” Bernie asked.

“Both,” Libby replied.

The winter’s snow had melted in the past two weeks, re. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...