- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

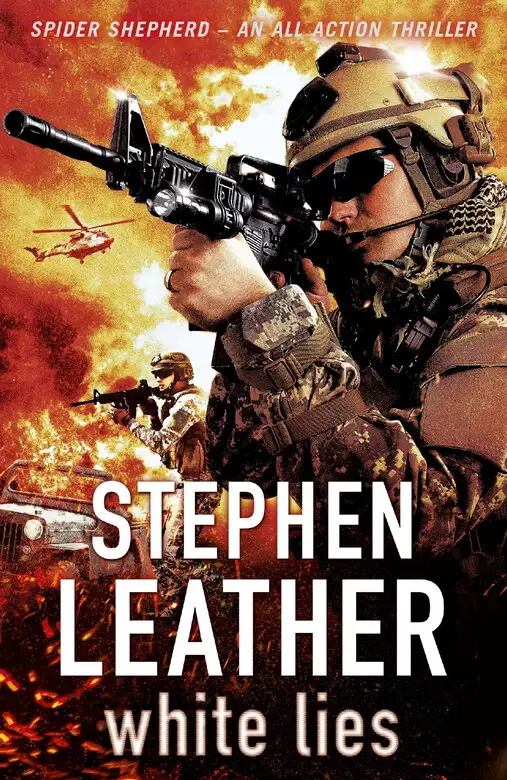

Synopsis

Dan “Spider” Shepherd is used to putting his life on the line – for his friends and for his job with MI5. So when one of his former apprentices is kidnapped in Pakistan, Shepherd doesn’t hesitate to join a rescue mission. But when the rescue plan goes horribly wrong, Shepherd ends up in the hands of Al-Qaeda terrorists. His SAS training is of little help as his captors torture him. Shepherd’s MI5 controller Charlotte Button is determined to get her man out of harm’s way, but to do that she’s going to have to break all the rules. Her only hope is to bring in America’s finest – the elite SEAL's who carried out Operation Neptune Spear – in a do-or-die operation to rescue the captives.

Release date: August 14, 2014

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

White Lies

Stephen Leather

There were three men sitting at the table listening intently as they finished off their plates of steak and chips. They were on their second bottle of red wine and a third had already been opened. They were in a small restaurant in a coastal village between Calais and Dunkirk, close to the border with Belgium. They had a table by a roaring fire that had shadows flickering over the roughly plastered walls.

Coatsworth waved his knife in the air for emphasis. ‘It’s the Wild West over here, mate. You can make money hand over fist if you know what you doing. I’ve got a pal who smuggles them on to trucks for a grand a go. He pays the driver two hundred of that and keeps eight hundred for himself. Gets maybe five on a truck. He makes four grand and the driver gets one. They almost never get caught but, if they do, the driver just says they snuck on and he knows nothing.’

‘Sounds good,’ said the man sitting opposite him. His name was Andy Bell. He was a few years younger than Coatsworth, his face burned from exposure to the sun. He was wearing a heavy green polo-necked jumper, combat trousers and Timberland boots.

‘He’s got an even better deal with trucks that have been built with secret compartments. Usually when the driver owns his own rig. You can build a compartment that holds three or four and they’ll never be found. He can charge four grand a go for that and the driver takes half. So that’s two grand a person, six grand a run.’

‘Why the fifty-fifty split?’ asked Bell.

‘It’s obvious,’ said another of the men at the table. Bruno Mercier was an Algerian, short and stocky with a crew cut and a diamond stud in his left ear. ‘Because if they get caught in a secret compartment, the driver can’t say he didn’t know.’

‘But most trucks aren’t checked, right?’ asked Bell.

‘They don’t have time,’ said Coatsworth. ‘Dover would grind to a halt if they searched every vehicle. The only problem is finding the right driver. That’s not easy. At least doing what we’re doing, we’re not beholden to anyone. No one can let us down. And more importantly, no one can grass us up.’

Bell nodded and popped another piece of steak into his mouth. Coatsworth emptied his glass and refilled it. He tried to pour more into Bell’s glass but Bell put his hand over the top. ‘It’ll help keep out the cold,’ said Coatsworth. ‘The English Channel gets bitter at night.’

‘Go on, then,’ said Bell, taking away his hand.

Coatsworth topped up Bell’s glass. ‘I’ll have some of that,’ said the fourth man at the table. Frankie Rainey was in his late twenties. He’d hung his fleece jacket over the back of his chair and had rolled up the sleeves of his denim shirt to reveal a tattoo on each forearm: a galleon in full sail and a dagger with a snake wound around it. One of his front teeth had gone black and the rest were stained from coffee and cigarettes. Coatsworth filled his glass.

‘Business is good, yeah?’ said Bell.

‘That’s why we need you,’ said Coatsworth, putting the bottle back on the table. ‘I was getting backed up.’

‘Where are you getting them from?’ asked Bell. ‘It’s not as if you can advertise smuggling runs to the UK, is it?’

‘I pay some middlemen to cruise around Calais and the other jumping-off ports,’ said Coatsworth. ‘We need a particular sort of refugee. Ideally some government official or army guy from Iraq or Afghanistan or Syria who’s managed to grab a decent wad before running away with his family. We’re looking for the happy medium. We don’t want the ones with no money. And if the guy’s got megabucks he can just buy his way into the UK by paying for passports.’

‘What, real ones? Real passports?’

‘Depends,’ said Coatsworth. ‘The really rich ones get the red-carpet treatment; invest a million quid in the UK and you and your family can all get passports. But twenty grand or so will get you a genuine passport, probably from some UK-born Asian who’s never left the country. He applies for a passport then sells it and forgets about travelling for ten years. But passports aren’t easy to get and we offer a cheaper way in. The trick is to find the ones with cash. It’s just a matter of separating the wheat from the chaff.’

‘The chaff being what?’

Coatsworth laughed. ‘The chaff being the morons with nothing, the ones who climb into refrigerated vans and freeze to death. My middlemen make sure that the clients have the cash to pay.’

‘Always cash?’

‘Mostly,’ said Coatsworth. ‘Dollars, euros or pounds, no funny Arab money, though. So long as it adds up to three grand sterling, I’m happy. But I’ve taken gold in the past. And jewellery.’ He pushed the sleeve of his jacket up his arm and showed Bell the watch on his wrist. It was a gold Rolex. ‘Got this off an Iraqi doctor. It’s the real thing, it’d cost you twenty grand in a jeweller’s.’

‘It’s genuine, right?’

Coatsworth scowled and held the watch under Bell’s chin. ‘Of course it’s bloody genuine. I’m not stupid. You can tell by the way the second hand moves. If it’s jerky it’s a fake. If it moves smoothly, it’s real.’

Bell looked at the watch and pulled a face. ‘I thought it was the other way around,’ he said.

Coatsworth frowned and pulled back his arm. He stared at the second hand and his frown deepened.

Rainey and Mercier burst out laughing but stopped when Coatsworth glared at them. ‘I’m yanking your chain,’ said Bell. ‘It’s kosher. You can tell just by looking at it. Quality.’

‘Yeah,’ said Coatsworth. He tapped the watch. ‘We should be heading out soon,’ he said. ‘We’ve got to meet the van in ten minutes.’

Bell sipped his wine. ‘So you think this is good money, long-term?’ he asked.

‘Best you’ll ever see,’ said Coatsworth. He leaned across the table. ‘I’ve been doing this for eighteen months now. During the summer the weather’s good enough for maybe twenty-five days. Less during spring and autumn. I’ve not done a winter yet but even then there’ll be days when I can do a run. The summer months, I was doing two runs a day. Eight customers each trip, that’s sixteen a day. Sixteen a day is forty-eight grand. OK, I’ve got costs. I pay the middlemen in France and I pay a guy to handle transport in the UK, and there’s fuel and expenses, but I can still clear forty-five grand a day. A day, mate. In August alone I pulled in more than a million quid.’

‘So what do you do with all the money, that’s too much cash to hide under the bed.’

‘I’ve got a guy who does my laundry,’ said Coatsworth. ‘He lives on Jersey, I take a run out to see him every month and leave the cash with him. He gets it into the banking system for a fee of ten per cent.’ He nodded at Rainey. ‘Frankie uses the same guy.’

‘That’s a lot, ten per cent,’ said Bell. He put his knife and fork down and belched. ‘Better out than in,’ he said.

Coatsworth shook his head. ‘It’s cheap as chips, mate. If you ever do get done the first thing they do is to go looking for the money and take it off you. My money’s in shell companies and trusts all around the world, safe from their grubby little hands. It’s worth paying ten per cent for. Trust me.’ He frowned. ‘What do you do with your money, then?’

‘Spend it,’ said Bell. His face broke into a grin. ‘But then I haven’t been earning a million quid a month. Running tourists out to the Holy Island doesn’t bring in the big bucks.’

‘Yeah, well, now you’re with me that’ll change. And you need to start thinking about what you’re going to do with the money you earn. The reason I brought you in is because I’m getting more customers than I can handle myself. It’s a growing market, mate, and you’ll grow with it.’ He looked at his watch again, drained his glass and stood up. ‘Time to go,’ he said, dropping a fifty-euro note on to the table and waving at the waiter, a grey-haired man in his fifties who doubled as the restaurant’s barman.

‘I need the toilet,’ said Bell.

‘Bladder like a marble,’ said Rainey.

‘Be quick about it,’ said Coatsworth. ‘We’ll be in the car.’

Bell hurried off to the toilet while Coatsworth, Rainey and Mercier headed outside and climbed into a large Mercedes. Rainey got into the driving seat and Coatsworth sat next to him. ‘Your mate’s not in there throwing up I hope,’ said Coatsworth.

‘He’ll be fine,’ said Rainey. He lit a cigarette and then offered the pack to Coatsworth. Coatsworth took one and handed the pack back to Mercier. ‘He’s short of a bob or two,’ Rainey continued. ‘He borrowed from the bank to buy his boat and he’s having trouble with the payments. Did you see the look on his face when you asked him what he did with his money? He was thinking about selling his boat, things were that bad.’

‘I hope it works out with him,’ said Coatsworth. ‘With two boats we make twice as much money.’

‘Amen to that,’ said Rainey. He started the engine.

The door to the restaurant opened and Bell jogged over to the car and climbed in the back next to Mercier. ‘Sorry,’ he said. ‘Better to do it here than at sea, right?’

Rainey edged the car out of the car park and on to the main road to Dunkirk. Bell wound down the window and let the breeze play over his face.

‘You’ve never been a smoker, Andy?’ asked Mercier.

‘Nah,’ said Bell.

‘You should take it up, now you’re on this crew. We smoke like chimneys.’

‘I think I’m getting a nicotine high from the secondary smoke,’ said Bell.

They drove to a garage that had closed for the night and parked behind it. ‘Where the fuck are they?’ asked Coatsworth. He looked at his watch and scowled.

‘I’ll call him,’ said Rainey. He pulled out his mobile phone but before he could make the call a large white Renault van pulled on to the garage forecourt and switched off its lights. It drove slowly around the garage and stopped next to the Mercedes.

Coatsworth climbed out, dropped what was left of his cigarette on to the tarmac and ground it out with his boot. Mercier and Bell joined him.

The driver of the van was a middle-aged Frenchman wrapped up in a sheepskin jacket and a thick red wool scarf wound several times around his neck. He climbed out of the cab and hugged Coatsworth, his breath reeking of garlic and brandy. ‘We have a problem,’ said the Frenchman as he broke away.

‘I pay you so I don’t have any problems,’ said Coatsworth.

The Frenchman looked pained. ‘One of them, he didn’t come up with the money.’

‘He’s in the van?’

The Frenchman nodded.

‘Why the hell’s he in the van? You know the deal, Alain. No money, no passage. If he doesn’t have the cash, he doesn’t get in the van.’

‘It’s complicated,’ said the Frenchman. ‘He’s with his family.’

‘Do I give a shit?’

‘He said he wanted to talk to you. I didn’t see the harm.’

‘You mean you want me to do your job, is that it? Well, how about you give me back the commission for the whole family? How about that?’

‘Ally, my friend, come on …’

‘Don’t give me that, you fat French fuck. I pay you to make sure that everything goes smoothly, not to bring the problems to me.’ He shook his head. ‘This ain’t right, Alain.’

‘He’s got kids.’

‘Yeah? You’ve got kids and I’ve got kids, we’ve all got kids. Having kids doesn’t get you a free pass in life.’

The Frenchman held up his hands. ‘I’m sorry. You’re right.’

‘I know I’m right,’ said Coatsworth. He gestured at the van. ‘OK, get them out.’ He turned to Bell and Mercier. ‘You need to search them. No weapons and no drugs. One bag each. They know that’s the deal so don’t take any shit from them.’

The Frenchman pulled open the rear doors. There were sixteen people sitting on the floor of the van: men, women and children. ‘Sortez!’ he said. ‘Get out!’

The first man out was a young Somalian, tall and with a wicked scar running down his left cheek. He was carrying a Manchester United holdall.

‘Over there,’ said Coatsworth, pointing to the front of the van.

Three Middle Eastern men were next out, all in jeans and pullovers and wearing heavy overcoats. ‘Where is the boat?’ asked one in a thick accent.

‘We search you, you pay, then we go to the boat,’ said Coatsworth.

‘We want to see the boat first,’ said the man.

‘No, you pay me first. Or you can fuck off. I don’t care which.’

The three men talked among themselves as they walked towards the front of the van. The one who had done the talking looked over his shoulder but looked away when he saw that Coatsworth was glaring at him.

A man and a woman climbed out of the van with a small boy who couldn’t have been more than six or seven years old. The boy was holding a toy dog and looking around excitedly as if he were on his way to a fairground. The woman had a black headscarf and the man was wearing a Muslim skullcap. The man was carrying two suitcases and the woman held the boy’s free hand.

‘Come on, come on,’ said Coatsworth. ‘We haven’t got all night.’

Three Somalian teenagers climbed out and stood looking around. They were carrying supermarket carrier bags stuffed with clothes. They were all tall and gangly, well over six feet. ‘What’s their story?’ Coatsworth asked the Frenchman.

‘Their father’s already in London. He sent them the money to come over. They’re OK. Good kids.’

Coatsworth pointed for the teenagers to go to the front of the van where Bell was patting down the three in the big coats. Mercier was on his knees, going through a suitcase.

‘This is the guy,’ said the Frenchman. ‘He’s Iraqi.’

A middle-aged man in a heavy leather jacket climbed out of the van. He held up his arms to lift down a small boy, then offered his hand to help down a teenage girl. His wife then handed him three large blue nylon holdalls and one by one he placed them on the ground before helping her down. The wife and daughter were wearing long coats and headscarves.

‘Does he speak English?’ Coatsworth asked the Frenchman. The Frenchman nodded.

Coatsworth pointed at the man. ‘I want a word with you,’ he said. The man hesitated so Coatsworth grabbed him by the arm and frogmarched him over to the Mercedes. ‘Where’s my money?’ he asked.

The Iraqi reached into his jacket pocket and pulled out an envelope. Coatsworth snatched it from him. It contained hundred-euro notes and Coatsworth flicked through them. ‘There’s only fifteen thousand euros here,’ he shouted. ‘That’s not what we agreed. You have to pay twenty thousand. What game are you fucking playing?’

The man’s wife was looking at them anxiously. Her son began to cry and she picked him up and whispered into his ear. The young girl slipped her arm through the woman’s and bit down on her lower lip as she watched Coatsworth argue with her father.

‘I gave him the deposit,’ said the Iraqi, gesturing at Alain. ‘Five hundred euros each. Two thousand euros.’

‘The deposit gets you on the list,’ said Coatsworth, waving the envelope in the man’s face. ‘The real money gets you on the boat. The fee is four grand a head. Four thousand pounds. Or five thousand euros. That’s the fee and you were told that before you signed on for this.’

‘My son is only three years old,’ protested the man. ‘He is a child.’

‘Four thousand pounds a head,’ said Coatsworth. ‘He’s got a head, hasn’t he? Four heads, sixteen thousand pounds. Or twenty thousand euros.’

The man held out his hands, palms up. ‘I don’t have twenty thousand euros. I have fifteen thousand. That’s all I have.’ There were tears in his eyes and his hands were trembling.

‘Bollocks,’ said Coatsworth. ‘You’ve got money, you’re just trying to cheat me and I’ll tell you now that’s not going to work.’

The man’s wife shouted something in Arabic and the man turned and shouted back at her.

Coatsworth put a hand on the man’s shoulder. ‘Don’t talk to her, talk to me,’ he snarled.

‘I don’t have twenty thousand euros,’ he said. ‘Not in cash. It’s in a bank. I can pay you when we get to England.’

‘Yeah, my cheque’ll be in the post and you won’t come in my mouth,’ said Coatsworth.

The Iraqi frowned. ‘I don’t understand,’ he said.

‘Then understand this. No money, no trip. You’ve enough for three people so I’ll take three of you. One of you will have to stay behind.’ He looked at the watch on the man’s wrist. It was a cheap Casio. ‘Does your wife have any jewellery? Any gold?’

The man shook his head. ‘We were robbed when we were in Turkey.’ The man’s wife walked towards them, the boy in her arms, and said something in Arabic to the man. He replied, and she started talking faster, her free arm waving in the air.

‘Bruno, get over here!’ Coatsworth called to Mercier. Mercier closed the suitcase he was searching and jogged over.

The Iraqi was speaking to his wife in Arabic. Coatsworth turned to Mercier. ‘What’s he saying?’

Mercier moved closer to Coatsworth. ‘She’s saying she thinks they should wait. And find another way to England. Says she doesn’t like you.’

Coatsworth laughed harshly. ‘Doesn’t like me? Doesn’t fucking like me?’ He pointed his finger at the woman. ‘You can fuck off back to Arab-land for all I care,’ he shouted. ‘There are plenty of people more than happy to pay me. You and your whole family can just fuck off and I’ll get someone else to take your place.’

The woman glared at him defiantly. Her husband stepped in front of her and began talking animatedly.

‘What’s he saying now?’ Coatsworth asked Mercier.

‘He’s calming her down,’ said the Algerian. ‘He says they’re to go ahead and he’ll follow once he’s got the cash.’ He listened for a few seconds and then nodded. ‘They’ve got family in Milton Keynes. Her uncle and her aunt. He wants her to stay with them until he gets over. Says he’ll get the money from the bank and come on the next run.’

Coatsworth nodded. ‘Finally he sees sense.’ A small group of men and women were still inside the van, watching what was going on. Coatsworth pointed at them. ‘Get the hell out now and bring your bags with you.’

The Iraqi man finished talking to his wife and came over to Coatsworth.

‘My wife, she is very upset,’ he said. ‘You have to understand, her brother and her cousin were killed this year. Her brother worked for the Ministry of the Interior and the Taliban weren’t happy about what he was doing with border controls. Her cousin was a teacher and she was killed because she taught a lesson about female political leaders. The Taliban shot her in the face. We had to leave, you understand?’

‘I hear sob stories like yours all the time, mate,’ said Coatsworth. ‘I’m not a charity, I’m a business. You pay, you go, you don’t, you stay. When you’ve got the extra five thousand euros I’ll take you.’ He gestured at the road. ‘Now on your bike.’

‘My bike?’ The Iraqi frowned. ‘My bike? I have no bike.’

‘Get lost,’ said Coatsworth.

‘But how do I get back to Calais?’

‘That’s not my problem,’ said Coatsworth.

‘You have to help me,’ pleaded the Iraqi.

Coatsworth reached inside his coat and pulled out a gun, a small semi-automatic. He pointed it in the Iraqi’s face. ‘I don’t have to do anything,’ he said. ‘Now fuck off.’

The Iraqi looked over at Bell but Bell just folded his arms and stared back at him. Mercier said something to the Iraqi in Arabic and the Iraqi opened his mouth to say something back but then he had a change of heart and walked away, his head down. Coatsworth turned to look at the woman. She put her arms around the two children. ‘Up to you, you can go with him or you can come to England. I don’t care either way.’

The woman nodded slowly. ‘We will go with you,’ she said. There was no disguising the hatred in her eyes, but she managed to force a smile. ‘Thank you, for what you are doing. We do not want to cause you any trouble.’

Coatsworth nodded curtly and put his gun away. ‘Finish searching them,’ he said to Mercier. As the Algerian went over to the refugees, Coatsworth turned to watch the Iraqi walking down the road towards Calais. ‘Stupid bastard,’ he muttered under his breath.

Bell and Mercier finished searching the refugees. They had found two kitchen knives in the suitcase of one of the Arab men and all the Somalians had been carrying knives. Bell tossed the knives into the boot of the Mercedes.

‘Line them up and tell them to get their money out,’ Coatsworth said.

Mercier shouted at the group in rapid Arabic, French and English. ‘Line up and get your money out now!’

The refugees did as they were told. Coatsworth walked along the line, taking the money from them and checking it. Once it was checked, he handed the notes to Mercier, who put them in a black backpack. When he reached the Iraqi woman and her two children, Coatsworth grunted and waved at the van. One of the Somalian teenagers helped her up.

When he reached the three Iraqi men, the one who had asked about the boat the first time had his chin up defiantly. ‘We want to see boat,’ he said.

‘Do you see any water here?’ asked Coatsworth.

The man frowned. ‘Water?’ he repeated.

‘The sea? Do you see the fucking sea? We’re two miles from the coast. When we get to the coast you’ll see the bloody boat.’ He held out his hand. ‘Now give me the money or you can walk back to Calais with that other prick.’

The man frowned, clearly not understanding what he was saying, so Coatsworth gestured at Mercier. ‘Tell him what I said and get them in the van.’ He took the backpack from Mercier, thrust in the last of the cash and took it over to the Mercedes. He tossed the backpack on top of the confiscated weapons and slammed the boot shut.

He got back into the Mercedes and watched the refugees climb into the van. The Frenchman slammed the doors shut and got back into the cab. Rainey offered him a cigarette and he took it. Rainey lit it and then lit one for himself.

Bell and Mercier got into the back of the Mercedes. Rainey gave Mercier a cigarette and then put the car in gear and followed the van down the road. There was no traffic and they reached the small harbour in just five minutes. The van pulled up next to a line of fisherman’s huts that had been locked up for the night. Rainey brought the Mercedes to a stop behind the van and switched off the headlights.

Two teenagers in heavy jackets and wool beanies walked over. Mercier wound down the window and spoke to them in rapid French. They answered. ‘All good,’ Mercier said to Coatsworth.

‘Let’s do it, then,’ said Coatsworth. ‘Open the boot, Frankie.’

Coatsworth climbed out of the car and went around to the back. He pulled out the backpack containing the money. Bell and Mercier joined him and retrieved their own bags.

Rainey got out and tossed the keys to one of the teenagers.

Coatsworth gestured at Mercier with his chin. ‘Tell them no joyriding and they’d better be here when we get back.’

As Mercier translated Coatsworth’s instructions, Rainey went around to the boot to get his bag, a Nike holdall. He slammed the boot shut.

The Frenchman had opened the van doors and the refugees climbed out and gathered together in a tight group like worried sheep.

‘Right, get them on to the boats, now,’ said Coatsworth. He waved goodbye to the Frenchman, who climbed into the van and drove off.

There was a gap in the sea wall leading to a flight of stone steps. At the bottom of the steps was a wooden jetty where two high-performance rigid inflatable boats were bobbing in the swell. Rainey and Mercier ushered the men, women and children down the stone stairs to the waiting ribs. Each was about twenty feet long with a solid hull surrounded by a flexible inflatable collar that allowed the vessel to stay afloat even if swamped in rough seas. Each had a single massive Yamaha engine at the stern. There were few faster boats around, and these were certainly faster than anything owned by the UK’s Border Force or HM Revenue and Customs. The boats were also virtually invisible to radar, making them the perfect smuggler’s boat. Each had dual controls at the bow and a double bench seat in the centre with spaces for eight people and nylon seat belts to keep them securely in place.

Mercier and Rainey dumped their bags in the bow and helped the refugees into the boats.

‘You didn’t say anything about guns,’ Bell muttered to Coatsworth.

‘What, you think I’m gonna be wandering around in the dark with thirty grand in my bag without some way of protecting myself?’ sneered Coatsworth. He pointed down at the Somalians who were fastening their seat belts. ‘For all we know they could be bloody pirates. You think I’m going out to sea with people I don’t know without a gun?’ He gestured at the group, who were giving him anxious looks and muttering among themselves. ‘Look, mate, the meek don’t inherit the earth and they sure as hell don’t get out of shitholes like Iraq and Afghanistan or those African countries where they chop off each other’s arms. Anyone who has made it this far has had to lie, cheat, steal and probably done a lot worse. Thieves, warlords and murderers, the odd torturer or two, they’re the ones who get this far.’

‘She’s a teacher, the wife of that guy you sent packing,’ said Bell.

‘Yeah, well, she’s the exception,’ said Coatsworth. ‘And how do we know she’s telling the truth? For all we know her husband could have been Saddam Hussein’s torturer-in-chief. Do you think teachers and farmers and bus drivers can get the money to escape from Iraq and get here? Do you think nice smiley people with a song in their hearts claw their way out?’ He shook his head. ‘No, mate. The bastards are the ones who make it out and they do it by climbing over everybody else. They do what it takes to survive.’

‘You can’t blame them for that,’ said Bell.

‘No, you can’t. But the sort of ruthlessness that got them this far is the sort of ruthlessness that could lead to them knifing me when we’re out at sea and throwing me overboard so that they get my money and my boat. That’s why we search them before we put them on board and why I carry a big gun. Got it?’

‘Got it,’ said Bell.

‘It’s for protection.’

Bell held up his hands. ‘I hear you, Ally. It’s not a problem.’

‘Good man. Now let’s get this cargo delivered.’

‘When are you going to tell me where we’re going?’ said Bell.

‘I’ve given the GPS coordinates to Frankie,’ said Coatsworth. ‘Don’t take it personal, mate. I’m the only one who knows the drop-off point.’

‘Keeping your cards close to your chest? I can understand that.’

Coatsworth slapped him on the back. ‘I’ve been doing this for a while and never come close to being caught,’ he said. ‘I want to keep it that way. Look, you’ll see it on the GPS anyway. We’re heading north, up to the Suffolk coast. Near a place called Southwold. It’s a quiet beach. I’ve used it before.’

‘That’s a long trip,’ said Bell. ‘Close to a hundred miles.’

‘A couple of hours,’ said Coatsworth. ‘The water’s quieter up there and there’s almost no Border Force activity. Not that it matters that much, our boats can outrun anything the government has. The only thing that can keep up with us is a helicopter and there’s almost zero chance of us coming across one.’ He slapped Bell on the back again and led him down the stairs. A thick chain had been fixed to the sea wall to give them something to hold on to as they made their way down.

Coatsworth climbed into the rib with Mercier. All the passengers were on board and Mercier was checking that they had all fastened their seat belts. Their luggage was lying on the floor, close to their feet.

Bell carefully climbed into his rib. It was a few feet longer than Coatsworth’s and the seats were laid out slightly differently in four rows of two. His passengers were already strapped in. The Iraqi woman was sitting in the front row with her son on her lap. Her daughter was in the seat next to her.

Bell walked over to her and held on to the back of her seat for balance. ‘Your boy needs to be in a seat,’ he said.

She shook her head fiercely. ‘He is too small. He will fall out.’

Bell looked at the boy and realised she had a point. He turned to Rainey. ‘Frankie, there’s a cupboard under your wheel with some life jackets in it. There’s a kid’s one there.’

Rainey bent down, pulled open a hatch, then straightened up with an orange life jacket in his hand. He tossed it to Bell and Bell handed it to the woman. ‘Put that on your boy, just in case.’

He went up to the bow and knelt down to reach into the storage bay. He pulled out another seven life jackets.

‘Ally never bothers,’ said Rainey.

‘Yeah, well, I’m the skipper of this boat and

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...