- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

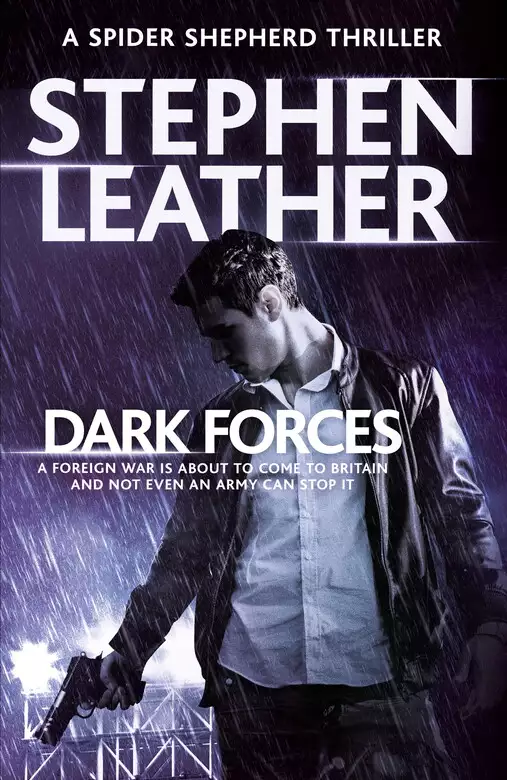

When you're caught between two evils, only the most decisive will survive. The thirteenth book in action supremo Stephen Leather's Spider Shepherd series is his most pulse-pounding yet . . .

A violent South London gang will be destroyed if Dan 'Spider' Shepherd can gather enough evidence against them while posing as a ruthless hitman. What he doesn't know is that his work as an undercover agent for MI5 is about to intersect with the biggest terrorist operation ever carried out on British soil.

Only weeks before Shepherd witnessed a highly skilled IS sniper escape from a targeted missile strike in Syria. But never in his wildest dreams did he expect to next come across the shooter in a grimy East London flat.

Spider's going to have to proceed with extreme caution if he is to prevent the death of hundreds of people, but at the same time, when the crucial moment comes he will have to act decisively. The clock is ticking and only he stands between us and Armageddon....

'Let Spider draw you into his web, you won't regret it' Sun

Release date: July 28, 2016

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Dark Forces

Stephen Leather

He was twenty-two years old, his skin the colour of weak coffee with plenty of milk. He had soft brown eyes that belonged more to a lovesick spaniel than the tried and tested assassin he was. His beard was long and bushy but his nails were neatly clipped and glistened as if they had been varnished. Around his head was a knotted black scarf with the white insignia of Islamic State, the caliphate that claimed authority over all Muslims around the world. His weapon was lying on a sandbag.

When he had first started sniping, he had used a Russian-made Dragunov SVD rifle, accurate up to six hundred metres. It was a lightweight and reliable weapon, capable of semi-automatic fire and equipped with a ten-round magazine. Most of his kills back then had been at around two hundred metres. His commander had spotted his skill with the weapon and had recommended him for specialist training. He was pulled off the front line and spent four weeks in the desert at a remote training camp.

There, he was introduced to the British L115A3 sniper rifle. It was the weapon of choice for snipers in the British SAS and the American Delta Force, and it hadn’t taken al-Hussain long to appreciate its advantages. It had been designed by Olympic target shooters and fired an 8.59mm round, the extra weight resulting in less deflection over long ranges. In fact, in the right hands the L115A3 could hit a human-sized target at 1,400 metres, and even at that distance the round would do more damage than a magnum bullet at close range.

The L115A3 was fitted with a suppressor to cut down the flash and noise it made. No one killed by a bullet from his L115A3 ever heard it coming. It was the perfect rifle for carrying around – it weighed less than seven kilograms and had a folding stock so it could easily be slid into a backpack.

It had an adjustable cheek-piece so that the marksman’s eye could be comfortably aligned with the Schmidt & Bender 25 × magnification scope. Al-Hussain put his eye to it now and made a slight adjustment to the focus. His target was a house just over a thousand metres away. It was home to the mother of a colonel in the Syrian Army, and today was her birthday. The colonel was a good son and, at just after eight o’clock, had arrived at the house to have breakfast with his mother. Fifteen minutes later, al-Hussain had taken up position on the roof. The colonel was a prime target and had been for the best part of a year.

The L115A3 cost thirty-five thousand dollars in the United States but more than double that in the Middle East. The Islamic State was careful who it gave the weapons to, but al-Hussain was an obvious choice. His notepad confirmed the benefits of using the British rifle. His kills went from an average of close to two hundred metres with the Dragunov to more than eight hundred. His kill rate increased too. With the Dragunov he averaged three kills a day on active service. With the L115A3, more often than not he recorded at least five. The magazine held only five shells but that was enough. Firing more than two shots in succession was likely to lead to his location being pinpointed. One was best. One shot, one kill. Then wait at least a few minutes before firing again. But al-Hussain wasn’t planning on shooting more than once. There were two SUVs outside the mother’s house and the soldiers had formed a perimeter around the building but the only target the sniper was interested in was the colonel.

‘Are we good to go?’ asked the man to the sniper’s right. He was Asian, bearded, with a crooked hooked nose, and spoke with an English accent. He was one of thousands of foreign jihadists who had crossed the border into Syria to fight alongside Islamic State. The other man, the one to the sniper’s left, was an Iraqi, darker-skinned and wearing glasses.

Al-Hussain spoke good English. His parents had sent him to one of the best schools in Damascus, the International School of Choueifat. The school had an indoor heated pool, a gymnasium, a grass football pitch, a 400-metre athletics track, basketball and tennis courts. Al-Hussain had been an able pupil and had made full use of the school’s sporting facilities.

Everything had changed when he had turned seventeen. Teenagers who had painted revolutionary slogans on a school wall had been arrested and tortured in the southern city of Deraa and thousands of people took to the streets to protest. The Syrian Army reacted by shooting the unarmed protesters, and by the summer of 2011 the protests had spread across the country. Al-Hussain had seen, first hand, the brutality of the government response. He saw his fellow students take up arms to defend themselves and at first he resisted, believing that peaceful protests would succeed eventually. He was wrong. The protests escalated and the country descended into civil war. What had been touted as an Arab Spring became a violent struggle as rebel brigades laid siege to government-controlled cities and towns, determined to end the reign of President Assad.

By the summer of 2013 more than a hundred thousand people had been killed and fighting had reached the capital, Damascus. In August of that year the Syrian government had killed hundreds of people on the outskirts of Damascus when they launched rockets filled with the nerve gas Sarin.

Al-Hussain’s parents decided they had had enough. They closed their house in Mezze and fled to Lebanon with their two daughters, begging Mohammed to go with them. He refused, telling them he had to stay and fight for his country. As his family fled, al-Hussain began killing with a vengeance. He knew that the struggle was no longer just about removing President Assad. It was a full-blown war in which there could be only one victor.

Syria had been run by the president’s Shia Alawite sect, but the country’s Sunni majority had been the underdogs for a long time and wanted nothing less than complete control. Russia and Iran wanted President Assad to continue running the country, as did Lebanon. Together they poured billions of dollars into supporting the regime, while the US, the UK and France, along with Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the rest of the Arab states, supported the Sunni-dominated opposition.

After the nerve gas attack, al-Hussain’s unit switched their allegiance to Islamic State, which had been formed from the rump of al-Qaeda’s operations in Iraq. Led by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, Islamic State had attracted thousands of foreign jihadists, lured by its promise to create an Islamic emirate from large chunks of Syria and Iraq. Islamic State grew quickly, funded in part by captured oilfields, taking first the provincial Syrian city of Raqqa and the Sunni city of Fallujah, in the western Iraqi province of Anbar.

As Islamic State grew, Mohammed al-Hussain was given ever more strategic targets. He was known as the sniper who never missed, and his notebook was filled with the names of high-ranking Syrian officers and politicians.

‘He’s coming out,’ said the Brit, but al-Hussain had already seen the front door open. The soldiers outside started moving, scanning the area for potential threats. Al-Hussain put his eye to the scope and began to control his breathing. Slow and even. There was ten feet between the door and the colonel’s SUV. A couple of seconds. More than enough time for an expert sniper like al-Hussain.

A figure appeared at the doorway and al-Hussain held his breath. His finger tightened on the trigger. It was important to squeeze, not pull. He saw a headscarf. The mother. He started breathing again, but slowly and tidally. She had her head against the colonel’s chest. He was hugging her. The door opened wider. She stepped back. He saw the green of the colonel’s uniform. He held his breath. Tightened his finger.

The phone in the breast pocket of his jacket buzzed. Al-Hussain leapt to his feet, clasped the rifle to his chest and headed across the roof. The two spotters looked up at him, their mouths open. ‘Run!’ he shouted, but they stayed where they were. He didn’t shout again. He concentrated on running at full speed to the stairwell. He reached the top and hurtled down the stone stairs. Just as he reached the ground floor a 45-kilogram Hellfire missile hit the roof at just under a thousand miles an hour.

Dan ‘Spider’ Shepherd stared at the screen. All he could see was whirling brown dust where once there had been a two-storey building. ‘Did we get them all?’ he asked.

Two airmen were sitting in front of him in high-backed beige leather chairs. They had control panels and joysticks in front of them and between them was a panel with two white telephones.

‘Maybe,’ said the man in the left-hand seat. He was Steve Morris, the flying officer in command, in his early forties with greying hair. Sitting next to him was Pilot Officer Denis Donoghue, in his thirties with ginger hair, cut short. ‘What do you think, Denis?’

‘The sniper was moving just before it hit. If he was quick enough he might have made it out. We got your two guys, guaranteed. Don’t think they knew what hit them.’

‘What about IR?’ asked Shepherd.

Donoghue reached out and clicked a switch. The image on the main screen changed to a greenish hue. They could just about make out the ruins of the building. ‘Not much help, I’m afraid,’ said Donoghue. ‘There isn’t a lot left when you get a direct hit from a Hellfire.’

‘Can we scan the surrounding area?’

Morris turned his joystick to the right. ‘No problem,’ he said. The drone banked to the right and so did the picture on the main screen in the middle of the display. The two screens to the left of it showed satellite images and maps, and above them was a tracker screen that indicated the location of the Predator. Below that was the head-up display that showed a radar ground image. But they were all staring at the main screen. Donoghue pulled the camera back, giving them a wider view of the area, still using the infrared camera.

The drone was an MQ-9, better known as the Predator B. Hunter-killer, built by General Atomics Aeronautical Systems at a cost of close to 17 million dollars. It had a 950-shaft-horsepower turboprop engine, a twenty-metre wingspan, a maximum speed of 300 m.p.h. and a range of a little more than a thousand miles. It could fly loaded for fourteen hours up to a height of fifteen thousand metres, carrying four Hellfire air-to-surface missiles and two Paveway laser-guided bombs.

One of the Hellfires had taken out the building, specifically an AGM-114P Hellfire II, specially designed to be fired from a high-altitude drone. The Hellfire air-to-surface missile was developed for tank-hunting and the nickname came from its initial designation of Helicopter Launched, Fire and Forget Missile. But the armed forces of the West soon realised that, when fired from a high-flying drone, the Hellfire could be a potent assassination tool for taking out high-value targets. It was the Israelis who had first used it against an individual when their air force killed Hamas leader Ahmed Yassin in 2004. But the Americans and British had taken the technique to a whole new level, using it to great effect in Pakistan, Somalia, Iraq and Syria. Among the terrorists killed by Hellfire missiles launched from drones were Al-Shabaab leader Ahmed Abdi Godane, and British-born Islamic State terrorist Mohammed Emwazi, also known as Jihadi John.

The Hellfire missile was efficient and, at less than a hundred thousand dollars a shot, cost-effective. It was just over five feet long, had a range of eight thousand metres and carried a nine-kilogram shaped charge that was more than capable of taking out a tank. It was, however, less effective against a stone building. While there was no doubt that the men on the roof would have died instantly, the sniper might well have survived, if he had made it outside.

Shepherd twisted in his seat. Alex Shaw, the mission coordinator, was sitting at his desk in front of six flat-screen monitors. He was in his early thirties with a receding hairline and wire-framed spectacles. ‘What do you think, Alex? Did we get him?’

‘I’d love to say yes, Spider, but there’s no doubt he was moving.’ He shrugged. ‘He could have got downstairs and out before the missile hit but he’d have to have been moving fast.’

Shepherd wrinkled his nose. The primary target had been a British jihadist, Ruhul Khan and it had been Khan they had spent four hours following until he had reached the roof. It was only when the sniper had unpacked his rifle that Shepherd realised what the men were up to. While the death of the British jihadist meant the operation had been a success, it was frustrating not to know if they’d succeeded in taking out the sniper.

Shaw stood up and stretched, then walked over to stand by Shepherd. Donoghue had switched the camera back to regular HD. There were several pick-up trucks racing away from the ruins of the building, and a dozen or so men running towards it. None of the men on the ground looked like the sniper. It was possible he’d made it to a truck, but unlikely. And if he had made it, there was no way of identifying him from the air.

‘We’ll hang around and wait for the smoke to clear,’ said Shaw. ‘They might pull out the bodies. Muslims like to bury their dead within twenty-four hours.’ He took out a packet of cigarettes. ‘Time for a quick smoke.’

‘Just give me a minute or two, will you, Alex?’ asked Shepherd. ‘Let’s see if we can work out what the sniper was aiming at.’

‘No problem,’ said Shaw, dropping back into his seat.

‘Start at about three hundred metres and work out,’ said Shepherd.

‘Are you on it, Steve?’ asked Shaw.

‘Heading two-five-zero,’ said Morris, slowly moving his joystick. ‘What are we looking for?’

‘Anything a sniper might be interested in,’ said Shepherd. ‘Military installation. Army patrol. Government building.’

‘It’s mainly residential,’ said Donoghue, peering at the main screen.

Shepherd stared at the screen. Donoghue was right. The area was almost all middle-class homes, many with well-tended gardens. Finding out who the occupants were would be next to impossible, and there were dozens of houses within the sniper’s range. There was movement at the top of the screen. Five vehicles, travelling fast. ‘What’s that?’ he asked.

Donoghue changed the camera and zoomed in on the convoy. Two army jeeps in front of a black SUV with tinted windows, followed by an army truck with a heavy machine-gun mounted on the top followed by a troop-carrier. ‘That’s someone important, right enough,’ said Donoghue.

Shepherd nodded. ‘How far from where the sniper was?’

‘A mile or so.’ Donoghue wrinkled his nose. ‘That’s a bit far, isn’t it?’

‘Not for a good one,’ said Shepherd. ‘And he looked as if he knew what he was doing.’ He pointed at the screen. ‘They’re probably running because of the explosion. Whoever that guy is, he’ll probably never know how close he came to taking a bullet.’

‘Or that HM Government saved his bacon,’ said Shaw. He grinned. ‘Well, not bacon, obviously.’

‘Can we get back to the house, see if the smoke’s cleared?’ said Shepherd. He stood and went over to Shaw’s station. ‘Can you get me close-ups of the sniper and his gun?’

‘No problem. It’ll take a few minutes. I’m not sure how good the images will be.’

‘We’ve got technical guys who can clean them up,’ said Shepherd.

‘Denis, could you handle that for our guest?’ said Shaw, then to Shepherd: ‘Thumb drive okay?’

‘Perfect.’

‘Put a selection of images on a thumb drive, Denis, while I pop out for a smoke.’ Shaw pushed himself up out of his chair.

‘I’m on it,’ said Donoghue.

Shaw opened a door and Shepherd followed him out. The unit was based in a container, the same size and shape as the ones used to carry goods on ships. There were two in a large hangar. Both were a dull yellow, with rubber wheels at either end so that they could be moved around, and large air-conditioning units attached to keep the occupants cool. The hangar was at RAF Waddington, four miles south of the city of Lincoln.

Shaw headed for the hangar entrance as he lit a cigarette. On the wall by the door was the badge of 13th Squadron – a lynx’s head in front of a dagger – and a motto: ADJUVAMUS TUENDO, ‘We Assist by Watching’. It was something of a misnomer as the squadron did much more than watch. Shaw blew smoke at the mid-morning sky. ‘It was like he had a sixth sense, wasn’t it? The way that sniper moved.’

‘Could he have heard the drone?’

Shaw flashed him an admonishing look. The men of 13th Squadron didn’t refer to the Predators as drones. They were RPAs, remotely piloted aircraft. Shepherd supposed it was because without the word ‘pilot’ in there somewhere, they might be considered surplus to requirements. Shepherd grinned and corrected himself. ‘RPA. Could he have heard the RPA?’

‘Not at the height we were at,’ said Shaw.

‘Must have spotters then, I guess.’

‘The two men with him were eyes on the target. They weren’t checking the sky.’

‘I meant other spotters. Somewhere else. In communication with him via radio or phone.’

‘I didn’t see any of them using phones or radios,’ said Shaw.

‘True,’ said Shepherd. ‘But he could have a phone set to vibrate. The phone vibrates, he grabs his gun and runs.’

‘Without warning his pals?’

‘He could have shouted as he ran. They froze. Bang.’

‘Our target was one of the guys with him. The Brit. Why are you so concerned about the one that got away?’

‘Usually snipers have just one spotter,’ said Shepherd. ‘Their job is to protect the sniper and help him by calling the wind and noting the shots. That guy had two. Plus it looks like there were more protecting him from a distance. That suggests to me he’s a valuable Islamic State resource. One of their best snipers. If he got away, I’d like at least to have some intel on him.’

‘The Brit who was with him. How long have you been on his tail?’

‘Khan’s been on our watch list since he entered Syria a year ago. He’s been posting some very nasty stuff on Facebook and Twitter.’

‘It was impressive the way you spotted him coming out of the mosque. I couldn’t tell him apart from the other men there.’

‘I’m good at recognising people, close up and from a distance.’

‘No question of that. I thought we were wasting our time when he got in that truck but then they picked up the sniper and went up on the roof. Kudos. But how did you spot him?’

‘Face partly. I’d seen his file in London and I never forget a face. But I can recognise body shapes too, the way people move, the way they hold themselves. That was more how I spotted Khan.’

‘And what is he? British-born Asian who got radicalised?’

‘In a nutshell,’ said Shepherd. ‘A year ago he was a computer-science student in Bradford. Dad’s a doctor, a GP. Mum’s a social worker. Go figure.’

‘I don’t understand it, do you? What the hell makes kids throw away their lives here and go to fight in the bloody desert?’

Shepherd shrugged. ‘It’s a form of brainwashing, if you ask me. Islamic State is a cult. And like any cult they can get their believers to do pretty much anything they want.’

Shaw blew smoke at the ground and watched it disperse in the wind. ‘What sort of religion is it that says booze and bacon are bad things?’ he said. ‘How can anyone in their right mind believe for one moment that a God, any God, has a thing about alcohol and pork? And that women should be kept covered and shackled? And that old men should have sex with underage girls? It’s fucking mad, isn’t it?’

‘I guess so. But it’s not peculiar to Islam. Jews can’t eat pork. Or seafood. And orthodox Jews won’t work on the Sabbath.’

‘Hey, I’m not singling out the Muslims,’ said Shaw. ‘It’s all religions. We’ve got a Sikh guy in the regiment. Sukhwinder, his name is, so you can imagine the ribbing he takes. Lovely guy. Bloody good airman. But he wears a turban, doesn’t cut his hair and always has to have his ceremonial dagger on him. I’ve asked him, does he really believe God wants him not to cut his hair and to wear a silly hat?’ Shaw grinned. ‘Didn’t use those exact words, obviously. He said, yeah, he believed it.’ He took another pull on his cigarette. ‘So here’s the thing. Great guy. Great airman. A true professional. But if he really, truly, honestly believes that God wants him to grow his hair long, he’s got mental-health issues. Seriously. He’s as fucking mad as those nutters in the desert. If he truly believes God is telling him not to cut his hair, how do I know that one day his God won’t tell him to pick up a rifle and blast away at non-believers? I don’t, right? How the hell can you trust someone who allows a fictional entity to dictate their actions?’

‘The world would be a much better place without religion – is that what you’re saying?’

‘I’m saying people should be allowed to believe in anything they want. Hell, there are still people who believe the earth is flat, despite all the evidence to the contrary. But the moment that belief starts to impact on others …’ He shrugged. ‘I don’t know. I just want the world to be a nicer, friendlier place and it’s not, and it feels to me it’s religion that’s doing the damage. That and sex.’

Shepherd smiled. ‘Sex?’

‘Haven’t you noticed? The more relaxed a country is about sex, the less violent they are. The South Americans, they hardly ever go to war.’

‘Argentina? The Falklands?’

‘That was more of a misunderstanding than a war. But you know what I mean. If you’re a young guy in Libya or Iraq or Pakistan, your chances of getting laid outside marriage are slim to none. They cover their women from head to toe, for a start. So all that male testosterone is swilling around with nowhere to go. Of course they’re going to get ultra-violent.’

‘So we should be sending hookers to Iraq and Libya, not troops?’

‘I’m just saying, if these Islamic State guys got laid more often they wouldn’t be going around chopping off so many heads. If Khan had been getting regular sex with a fit bird in Bradford, I doubt he’d be in such a rush to go fighting in the desert.’

‘It’s an interesting theory,’ said Shepherd. ‘But if I were you I’d keep it to myself.’

‘Yeah, they took away our suggestions box years ago,’ said Shaw. He flicked away the remains of his cigarette. ‘I’ll get you your thumb drive and you can be on your way.’

They went back inside the container. Donoghue had the thumb drive ready and handed it to Shepherd, who thanked him and studied the main screen. The dust and smoke had pretty much dispersed. The roof and upper floor had been reduced to rubble but the ground floor was still standing. ‘No sign of any bodies?’ asked Shepherd.

‘Anything on the roof would have been vaporised, pretty much,’ said Morris. ‘If there was anyone on the ground floor, we won’t know until they start clearing up, and at the moment that’s not happening. They’re keeping their distance. Probably afraid we’ll let fly a second missile. We can hang around for a few hours but I won’t be holding my breath.’

‘Probably not worth it,’ Shepherd said. ‘Like you say, he’s either vaporised or well out of the area.’ He looked at his watch and flashed Shaw a tight smile. ‘I’ve got to be somewhere, anyway.’

‘A hot date?’ asked Shaw.

‘I wish,’ said Shepherd. He couldn’t tell Shaw he was heading off to kill someone and this time it was going to be up close and personal.

Mohammed al-Hussain was driven to see his commander in the back of a nondescript saloon car, a twelve-year-old Toyota with darkened windows. The commander was based in a compound on the outskirts of Palmyra, pretty much in the middle of Syria. Palmyra had been gutted by the fierce fighting between the Syrian government and Islamic State fighters. The city’s historic Roman theatre had been left virtually untouched and was now used as a place of execution, the victims usually forced to wear orange jumpsuits before they were decapitated, often by children.

The commander was Azmar al-Lihaib, an Iraqi who had been one of the first to join Islamic State. His unit worked independently, often choosing its own targets, though special requests were regularly handed down from the IS High Command.

Al-Hussain was dog-tired. He hadn’t slept for more than thirty-six hours. The khat leaves he was chewing went some way to keeping him awake but his eyelids kept closing as he rested his head against the window. He must have dozed for a while because the car lurched to a halt unexpectedly causing him to jerk upright, putting his hands up defensively. They had arrived at al-Lihaib’s compound. The men in the unit never wore uniforms and the Toyota’s occupants were checked by two men in flowing gowns, holding Kalashnikovs, with ammunition belts strung across their chests.

They drove through the gates and parked next to a disused fountain. Al-Hussain climbed out and pulled the backpack after him. He never went anywhere without his rifle and even slept with it by his side. He spat out what was left of the khat, and green phlegm splattered across the dusty ground.

Two more guards stood at either side of an arched doorway and moved aside to allow him through. He walked down a gloomy corridor, his sandals scuffing along the stone floor. There was a pair of double wooden doors at the far end with another two guards. One knocked and opened them as al-Hussain approached. He hesitated for a second before he went through.

It was a large room with thick rugs on the floor and heavy purple curtains covering the window. Commander al-Lihaib was sitting cross-legged beside an octagonal wooden table inlaid with mother-of-pearl on which stood a long-spouted brass teapot and two small brass cups. Even when he was sitting down it was obvious that al-Lihaib was a big man and tall, while his Kalashnikov, on a cushion beside him, looked like a toy against his shovel-sized hands. He was in his forties with hooded eyes and cheeks flecked with black scars that looked more like a skin condition than old wounds. Like many Islamic fighters his beard was long and straggly, and the backs of his hands were matted with hair. His fingernails were yellowed and gnarled and his teeth were chipped and greying. He waved al-Hussain to the other side of the table, then poured tea into the cups as the younger man sat and crossed his legs.

Al-Lihaib waited until they had both sipped their hot mint tea before he spoke. ‘You had a lucky escape,’ he said.

‘Allah was looking over me,’ said al-Hussain.

‘As were your team, thankfully,’ said al-Lihaib. ‘It is rare actually to see a drone but one of the men caught the sun glinting off it, then the missile being launched.’

‘I barely made it off the roof,’ said al-Hussain. ‘I’m sorry about the men who were with me. I shouted a warning but they froze.’

‘They had been briefed?’

‘They had been told to follow my orders immediately. As I said, they froze.’

‘You had only seconds in which to act,’ said al-Lihaib.

‘The question is, how did they know where I would be?’ said al-Hussain. ‘I was told of the location only an hour before I got there.’

‘And we learned of the colonel’s visit only that morning, by which time the drone was almost certainly in the air.’ Al-Lihaib sipped his tea.

‘Could the drone have been protecting the colonel?’ asked al-Hussain.

‘Out of the question,’ said the commander. ‘The Americans and the British do not use their drones to protect foreigners, only to attack their enemies.’

‘Then how did they know I would be on the roof?’

‘They didn’t,’ said al-Lihaib. ‘They couldn’t have.’

‘Then why?’

Al-Lihaib took another sip of his tea. ‘It could only have been the British jihadist they were after,’ he said. ‘The British have been using the drones to track and kill their own people. They must have been following him, watched him join you and go to the roof. Once they had a clear shot, they launched their missile.’ He smiled grimly. ‘You were in the wrong place at the wrong time. It was the Brit they wanted to kill. You would have been collateral damage.’

Al-Hussain drank some tea.

‘Your parents are in Lebanon?’ asked al-Lihaib.

Al-Hussain nodded. ‘They fled in 2013.’

‘They are safe?’

Al-Hussain shrugged. ‘I haven’t spoken to them since they left. I told them they should stay. We are Syrians, this is our country. We should fight for it.’

‘Sometimes we have to take the fight to the enemy,’ said al-Lihaib. ‘Like the martyrs did on Nine Eleven. The whole world took notice. And in Paris. We hurt the French, we made them bleed. They learned a lesson – you hurt us and we hurt you. An eye for an eye.’

Al-Hussain nodded but didn’t say anything. Al-Lihaib reached inside his robe and took out a passp

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...