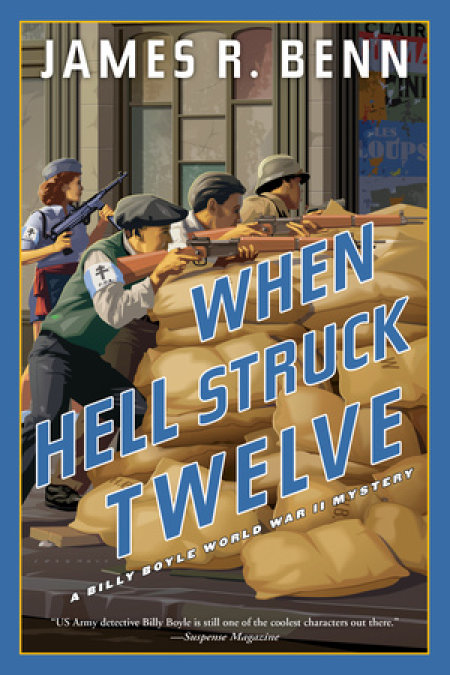

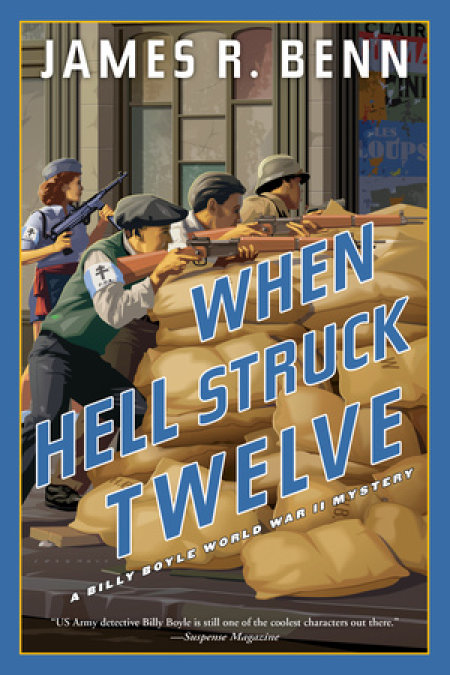

When Hell Struck Twelve

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

US Army detective Billy Boyle and Lieutenant Kaz are assigned to the French Resistance with delicate orders: help them with their mission, but only enough to keep up a deception campaign-the outcome of the war depends on it.

August, 1944: US Army Captain Billy Boyle is assigned to track down a French traitor, code named Atlantik, who is delivering classified Allied plans to German leaders in occupied Paris. The Resistance is also hot on his trail, and out for blood, after Atlantik's previous betrayals led to the death of many of their members. But the plans Atlantik carries were leaked on purpose, a ruse devised by a colonel to obscure the Allied army's real intentions to bypass Paris in a race to the German border.

Now Billy and Kaz are assigned to the Resistance with orders to not let them capture the traitor: the deception campaign is too important. Playing a delicate game, the chase must be close enough to spur the traitor on and visible enough to insure the Germans trust Atlantik. The outcome of the war may well depend on it.

Release date: September 3, 2019

Publisher: Soho Crime

Print pages: 360

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

When Hell Struck Twelve

James R. Benn

THE FALAISE GAP, NOR THERN FR ANCE

August 1944

The ground was a carpet of gray corpses. They lay on the hillside in scattered clumps and on the valley floor below like a river flowing in from hell itself. Blasted by shells and bombs, ripped and torn by strafing aircraft, remnants of the once-mighty German army in Normandy were dead or dying in droves as they tried to escape the trap closing in on them.

Those desperate enough were struggling to flee the carnage, and the only way to do that was to drive us off this goddamn hill. Hill 262, according to the map. Two hundred and sixty-two meters high, it towered above the eastern road from Falaise and the green meadows littered with German dead, their field-gray uniforms coated in swirling dust and caked crimson with blood.

Across the valley, somewhere to the south, General Patton’s Third Army was advancing on a long end run to slam the door on the German escape route. Patton was drawing near, but not fast enough to stop the stream of surviving Krauts from fighting their way out of the slowly closing trap. The enemy was in a tight spot, backed up on the road for thirty miles or so to the west, stuck in a shrinking pocket enveloped by Allied armies. But the pocket wasn’t zipped up tight, not yet. We were in the right place, but not strong enough to lock it up. Patton’s tanks were strong enough, but too far distant.

Even so, the valley was a shooting gallery filled with burning vehicles and men dying as they made their way forward on foot. Everything from long-range artillery to tank shells hit the valley floor with explosive bursts, churning up earth and igniting fuel tanks, plumes of yellow flame and black smoke dotting the roadway for miles. The rancid odor of death rose up on the blisteringly hot winds from the valley below, clawing at the back of my throat.

“Anything, Captain Boyle?” Lieutenant Feliks Kanski asked, as I hunched over the radio in the back of my jeep, which was parked next to a shell-shattered tree trunk, camouflaged by tangled limbs and dying leaves. There were few safe places within the square mile we possessed on this hill, and I was glad of what cover it offered. I shook my head as I gave my call sign over and over again, broadcasting on the frequency we’d been assigned.

“Keep at it, we need ammunition,” Feliks said. His face was gaunt, his skin pale under the filth of three days on this hilltop. Sweat poured down his temples under the distinctive British tin pot helmet shading his eyes. Feliks was with the Polish 1st Armoured Division, as was everyone else on Hill 262.

Well, not everyone. I was here, along with my buddy Kaz. Lieutenant Piotr Kazimierz, that is. Kaz was a member of the Polish army-in-exile, but he wasn’t with Feliks’s frontline unit. He and I were part of a different outfit. We worked for General Eisenhower and wore the shoulder patch of the Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force. SHAEF. We’d arrived yesterday as part of a Canadian supply column that had run into bad luck in the form of a couple of Panther tanks who got us in their sights and took out all six trucks. We’d been in a jeep, and either they didn’t spot us or felt we weren’t worth a high explosive shell. After that, Hill 262 had been surrounded. Tanks and German paratroopers attacked on one side, fanatical SS troops on the other.

I gave Feliks my canteen. There wasn’t much left, but he needed it more than I did. He took a sip and handed it back as static crackled, and I finally heard a voice. In English, thankfully. It was the 4th Canadian Armoured, and they had good news. I acknowledged the message and signed off.

“Supply drop at 0900,” I said, which meant the planes were close. Feliks grinned.

“Good,” he said. “I will pass the word. It is about time. We’re down to fifty rounds per man. Some of the tanks have only a few shells left.”

The Poles had been fighting for days. That hadn’t been part of the plan. By now the northern and southern pincers should have linked up and had the Krauts trapped within a deadly embrace. Instead, Hill 262 was on its own and struggling to hold on.

Struggling in more ways than one. Every Polish soldier knew what surrender to the SS meant. Execution. With elements of two SS panzer divisions attacking from the west, trying to pry open an escape route for their pals inside the pocket, there was only one choice—fight to the death.

Every Pole on this hill knew about the Warsaw Uprising. The Polish Home Army had revolted and fought the Germans, expecting the Soviet army to liberate the city. But the Russians had not come to their aid. They halted, allowing SS troops to pour in and put down the rebellion. Tens of thousands of civilians were massacred as the Russians waited for the Nazis to wipe out the Home Army, which they considered a potential threat to Soviet rule. No Polish soldier would expect any mercy from the SS. Or give any, not after Warsaw. Not after five years of ruthless occupation and that last terrible bloodbath.

Shells exploded on the hillside, a reminder that the Germans in the valley still had deadly hardware and could use it effectively. Artillery sounded from the north, the 4th Canadian Armored boys trying to fight their way through the Kraut paratroopers to get to us and having a tough time of it. Small arms fire crackled along the line, but it was impossible to tell who was shooting at whom and with what effect.

I dashed over to Kaz, shells falling closer and closer. He was in a trench near an old hunting lodge, the only building on the hill. It had been pressed into service as a hospital and was crammed with wounded, Pole and German alike. Outside the lodge, several hundred prisoners were huddled together, guarded by Polish soldiers who’d been bandaged up but could manage guard duty.

“Did you get through?” Kaz asked, removing his steel-rimmed spectacles and cleaning them with the spotless white handkerchief he had managed to produce from one of his pockets. Monogrammed, no less, with his initials and family crest. Kaz may have been a lowly lieutenant in the eyes of the army, but he was a baron of the Augustus clan, and probably one of the few Polish nobles left alive.

“Yeah. Our Canadian pals said an airdrop of supplies is on the way. These guys giving you any trouble?”

“None at all,” Kaz said, putting on his glasses and gazing out over the sullen prisoners sitting on trampled grass, his Sten gun resting on the lip of the trench. It might have been the submachine gun, or the terrible scar that cut across the side of Kaz’s face. Both were frightening enough. “I think most are glad to be out of the war. Or in shock from the experience in that valley.”

I unslung my Thompson submachine gun and leaned against the trench wall. Kaz was right. By the looks on their faces, these Fritzes had had enough. They’d come through the valley of death and been captured by Polish tankers. Lucky to have survived both, few of them saw any percentage in making a run for it. If they weren’t killed outright, all they had to look forward to was more fighting and a high likelihood of dying on the dusty road to Paris.

Everybody wanted to get to Paris. GIs dreamt of it, a magical, near-mythical place of life, joy, wine, and women. French Resistance fighters wanted it for everything it meant to their nation still in chains. Germans wanted it for the safety it promised, or perhaps as a last chance for glamourous living and loot to carry back to the Reich.

I had my own reasons for getting to Paris.

“Still no SS?” I asked Kaz, after a quick survey of the POWs.

“No,” Kaz replied. “No SS prisoners. They fight to the end. As do our men. We are in France, but between Poles and the SS, it is still Poland. It is still Warsaw.”

“Fine by me,” I said. “Last thing we need are die-hard Nazis talking these boys into making a break for it.”

The POWs were the reason we were here. One of our jobs in the SHAEF Office of Special Investigations was prisoner interrogation. Well, one of Kaz’s jobs, to tell the truth. He was the one who spoke half a dozen languages fluently and a bunch of others passably. When we had nothing that needed actual investigating, our boss put us on this detail. Which had only extended to receiving the prisoners when they were brought back from the front lines. But Kaz couldn’t wait. He wanted to catch up with his Polish brethren, Feliks in particular. Feliks had intelligence contacts with the Home Army in occupied Poland, and Kaz had recently discovered that his younger sister Angelika was still alive, which was a very good thing. But she was working with the Polish underground, a very dangerous thing.

With the Warsaw Uprising and the slaughter of Polish civilians and fighters by the Nazis, Kaz was desperate to obtain whatever information he could. So, we invited ourselves along on that supply run. The brass wanted prisoners, especially officers, to interrogate about Kraut plans to defend Paris. That was the next stop in this campaign, once we bagged the remnants of the German army in the valley below. Which I’m sure had looked a whole lot easier on paper.

The Poles had a good haul of prisoners but no place to hold them. Our role should have been a walk in the park. Bring in the supplies and drive out the most senior POWs in the empty trucks. But war had a way of making even the simplest plan an unimaginable mess, and here we were smack in the middle of one. Feliks hadn’t heard a damn thing about Angelika, the trucks were blown to hell and gone, and we were battling enemy forces intent on overrunning our position and hightailing it to the City of Light or wherever the Krauts were planning on making their next stand.

“Do you hear it?” Kaz said, nudging me as he kept one eye on the prisoners. I did. The low rumble of C-47 cargo planes approaching. Shouts and cheers went up from the Poles dug in around us. Even the German prisoners looked happy, understanding with a soldier’s intuition that this sound meant chow and cigarettes. “There!”

Kaz pointed to the north as the sound of twin-engine aircraft grew in intensity, becoming their throbbing engines louder and more insistent. Then the first planes appeared, drawing closer as parachutes fell behind them, blossoming against the bright blue sky. Dozens of canisters floated beneath the white canopies as the flight of C-47s banked away from the anti-aircraft fire rising from the valley floor.

I kept my eye on the parachutes. They were too far away. The first ones landed far short of our positions, close to the Germans at the base of the hill. The rest drifted, snarling their cords in the trees on a ridgeline a quarter of a mile or more away. A groan went up from the men dug in around us. Even the prisoners looked disappointed.

“That’s where we left from yesterday,” Kaz said. “They dropped them to the Canadians, the fools.”

“They’ll break through to us,” I said, trying to sound confident. “And they’ll bring the supplies. It won’t be long.”

“We should have been back by now, interrogating these Nazi officers,” Kaz said, swinging his Sten gun to take in the prisoners sitting in the grass. Some of them ducked. Others laughed disdainfully at this unseemly display of nerves on the part of their Kameraden. “Perhaps we should start. We have a major and several captains here.”

“No,” I said. “We need to separate them. A guy won’t snitch if he knows he’s going to be tossed back in the clink with his pals. Too dangerous.” That was one of the first things my dad taught me back in Boston. He was a homicide detective, and he had started training me to follow in the family business before I was in long pants.

“Yes, I see,” Kaz said. “Besides, some of them may believe they will be freed after the next attack. They may have guessed we are low on ammunition.”

As if on cue, mortar rounds sailed over our heads, exploding around us. This time, everyone ducked. I told Kaz to stay put and ran low as another flurry of explosions dropped in among the entrenchments.

It was another attack. We were dug in deep, so mortar rounds weren’t much of a threat unless your foxhole took a direct hit. But it did tend to make you keep your head down, which was a problem if a few hundred pissed-off Krauts were advancing in your direction.

I ran by tanks, camouflaged by leafy branches and hidden in the rocky terrain. There was no activity on the hillside facing the valley road, just the ceaseless crump of distant artillery punishing the Germans below. I scuttled along behind the men, dug in all along the ridge. Nothing sounded other than the occasional rippling rattle of rifle fire.

On the northwest side of the hill, it was much the same. I dove into a foxhole already crowded with Poles manning a machine gun as another round of mortar fire sent shrapnel flying. I risked a quick glance above the logs protecting the gunners. Off to the left, a gulley ran down the hill, dotted with the bodies of Germans who’d tried to break through. These were the SS trying to loosen our hold on this hill so their pals could get out of the trap. By the twisted tangles of corpses, I didn’t see them trying that route again.

On the right flank, the ground sloped gently downward, a line of trees and shrubs to the side obscuring my vision. I strained to see any sign of movement through the greenery, but no dice. One of the Poles used his binoculars and shook his head as he let them drop to his chest. Nothing.

My gaze wandered to the grassy field in front of us. Between the gully and the trees, tall grasses browned by the August sun bent as a warm gust brushed against them. No sign of Krauts.

Then I saw it. Clumps of grass that didn’t bend with the breeze. Camouflage stuck on helmets. The enemy crawling silently forward on their bellies as we looked in all the obvious places.

“Szkopy,” I said, nudging the gunner. He nodded, having just spotted them. His loader lifted the belt of .30 caliber ammo from the metal box and held it up. He had less than fifty rounds. There were a lot more szkopy than that. Kaz said it meant castrated ram, and the free Poles had adopted it as slang for the SS.

“I’ll get more ammo,” I said, and rolled out of the emplacement. I ran back to the tanks, ignoring the explosions that were becoming less frequent. That was not good; it meant the castrated rams were getting closer.

“Krauts!” I yelled to Feliks, who was up in the turret shouting into his radio. I told him where and that we needed .30 caliber ammo.

“We are out, damn it!” he yelled, throwing down the receiver. “The relief column is still held up. How many?”

“Hard to say. Couple hundred at least. They’re crawling up the grassy slope, going slow. They don’t know we’ve spotted them,” I said. “The machine gun covering that ground is down to their last belt.”

“We can’t depress our guns to shoot downhill either,” Feliks said. “If they break through, it will be a slaughter. But we still have these.” He patted the big .50 caliber machine gun mounted on the turret. It was mainly for anti-aircraft protection, and the way it was set up, the gunner would have to stand exposed to enemy fire to use it. Risky, but with the Luftwaffe absent from the skies, there was a lot of ammo left.

Feliks signaled to one of the other tanks, and their treads spat dirt as they turned and rumbled off to the ridgeline. Feliks and the other tank commander held onto their guns, feet braced on the tank’s hull as they moved forward. I ran ahead to the machine gun pit, where the gunners were nodding their heads. They’d heard the tanks, felt the ground tremble as they approached, and knew help was at hand. I prayed it was enough. The Germans, crawling on their bellies, must have felt the tanks

coming as well.

They rose up, running and screaming, firing as they came, all pretense of stealth abandoned as they made for the thin line of trenches dug in along the ridge. The gunner squeezed off a few rounds, aiming carefully. Men fell, but more came on. Bullets thumped into the logs and sandbags, zinging through the air above out heads and kicking up stones and dirt all around us.

The gunner’s head snapped back, a bullet above one eye. His loader pushed the body away and fired, going through most of the ammo in his rage.

Where was Feliks? I could hear the roar of the Sherman’s radial engine, but no firing.

I fired my Thompson as the gunner finished off his ammo. He grabbed a rifle and began firing. Up and down the line, men shot at the advancing SS with slow, deliberate volleys, each man counting down to his final bullet.

There were too many of them. Some dropped dead, others rolled in the grass clutching wounds, but far more pressed on, faces blackened with dirt and gunpowder, snarling screams fueled by doses of Schnapps, fanaticism, and hatred for the subhuman Poles.

They came closer. The man next to me fired his last bullet. I handed him my pistol as a grenade exploded, showering us with dirt. I tossed my last grenade down the hill, screaming for Feliks as the Krauts got close enough to make out the SS runes on their collar tabs.

An engine roared directly above us, the Sherman’s treads halting inches from my head. The .50 caliber machine gun spewed fire, Feliks’s enraged screams loud enough to be heard between bursts. The rounds shattered the Germans, the second tank joining in with a crossfire that caught the SS in the open, ripping into flesh and bone, turning men into plumes of pink mist.

The machine guns were loaded with tracer rounds, bullets with a pyrotechnic charge that lit up and helped gunners aim at moving aircraft. Hitting men at this range, it set their clothing and flesh afire. The tracers ignited the dry grass, the wind fanning the flames as the SS tried to fall back, bullets striking them, sending up sprays of blood, severing limbs, slamming the dead and wounded into the burning earth.

“Warszawa! Warszawa!” The chant rose up from along the line, men standing and shaking their fists as Feliks and the other tanker unleashed their orgy of death. The grass burned. The dead and wounded burned. Shrieks of pain overcame even the chatter of the machine guns, which finally ceased for lack of targets.

I stood as well, listening to the Poles shout their revenge for the massacres in Warsaw. In the midst of all the yelling, I heard a familiar voice, and saw Kaz join us. He chanted Warszawa with the rest of them, tears streaming through the dirt and dust on his cheeks.

The last shots and shouts faded away as the Poles stopped, stunned at their victory. Feliks jumped down from his tank, pistol at the ready. But there was no need. The smoke-filled field held only the dead and dying. Several SS troopers tried to drag themselves through the fire, their uniforms smoldering. Their cries and screams died as they did, bleeding, choking, and burning before us.

“Let them burn,” Kaz said, his jaw clenched tight. “Hell is too good for them.”

“Niech płoną,” Feliks said, adding his agreement.

I found nothing in that sentiment to argue with. What strange creatures this war has made us.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...