- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

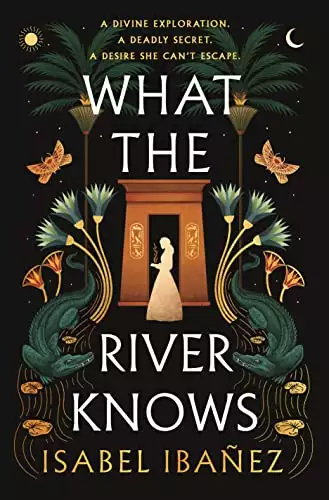

The Mummy meets Death on the Nile in this lush, immersive historical fantasy, filled with adventure, a rivals-to-lovers romance, and a dangerous race.

A divine exploration. A deadly secret. A desire she can't escape.

Bolivian-Argentinian Inez Olivera belongs to the glittering upper society of nineteenth century Buenos Aires, and like the rest of the world, the town is steeped in old world magic that's been largely left behind or forgotten. Inez has everything a girl might want, except for the one thing she yearns for the most: her globetrotting parents - who frequently leave her behind when they venture off on their exploring adventures.

When she receives word of their tragic deaths, Inez inherits their massive fortune and a mysterious guardian, an rchaeologist in partnership with his Egyptian brother-in-law. Yearning for answers, Inez sails to Cairo, bringing her sketch pads and an ancient golden ring her father sent to her for safekeeping before he died. But upon her arrival, the old world magic tethered to the ring pulls her down a path where she soon discovers there's more to her parent's disappearance than what her guardian led her to believe.

With her guardian's infuriatingly handsome assistant thwarting her at every turn, Inez must rely on ancient magic to uncover the truth about her parent's disappearance-or risk becoming a pawn in a larger game that will kill her.

---

'Expertly plotted, explosively adventurous, and burning with romance' Stephanie Garber

'A delightful read' Jodi Picoult

'Phenomenal' Mary E. Pearson

'As thrilling as it is insightful' J. Elle

'Sweeping' Elizabeth Lim

'Swoon-worthy' Rachel Griffin

'Luminous' Rebecca Ross

(P) 2023 Hodder & Stoughton Limited

Release date: November 14, 2023

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

What the River Knows

Isabel Ibañez

Never say you know the last word about any human heart.

—HENRY JAMES

AUGUST 1884

A letter changed my life.

I’d waited for it all day hidden in the old potter’s shed, away from Tía Lorena and her two daughters, one I loved and the other who didn’t love me. My hideout barely stood up straight, being old and rickety; one strong wind might blow the whole thing over. Golden afternoon light forced itself in through the smudged window. I furrowed my brow, tapping my pencil against my bottom lip, and tried not to think about my parents.

Their letter wouldn’t arrive for another hour yet.

If it was coming at all.

I glanced at the sketch pad propped against my knees and made myself more comfortable in the ancient porcelain bathtub. The remnants of old magic shrouded my frame, but barely. The spell had been cast long ago, and too many hands had handled the tub for me to be completely hidden. That was the trouble with most magic-touched things. Any traces of the original spell cast were faint, fading slowly anytime it passed hands. But that didn’t stop my father from collecting as many magically tainted objects as he could. The manor was filled with worn shoes that grew flowers from the soles, and mirrors that sang as you walked by them, and chests that spewed bubbles whenever opened.

Outside, my younger cousin, Elvira, hollered my name. The unladylike shrill would almost certainly displease Tía Lorena. She encouraged moderate tones, unless, of course, she was the one talking. Her voice could reach astonishing decibels.

Often aimed in my direction.

“Inez!” Elvira cried.

I was too much in a wretched mood for conversation.

I sank lower in the tub, the sound of my prima rustling outside the wooden building, yelling my name again as she searched the lush garden, under a bushy fern and behind the trunk of a lemon tree. But I kept quiet in case Elvira was with her older sister, Amaranta. My least favorite cousin who never had a stain on her gown or a curl out of place. Who never screeched or said anything in a shrill tone.

Through the slits of the wooden panels, I caught sight of Elvira trampling on innocent flowerbeds. I smothered a laugh when she stepped into a pot of lilies, yelling a curse I knew her mother also wouldn’t appreciate.

Moderate tones and no cursing.

I really ought to reveal myself before she sullied yet another pair of her delicate leather shoes. But until the mailman arrived, I wouldn’t be fit company for anyone.

Any minute he’d arrive with the post.

Today might finally be the day I’d have an answer from Mamá and Papá. Tía Lorena had wanted to take me into town, but I’d declined and stayed hidden all afternoon in case she forced me out of the house. My parents chose her and my two cousins to keep me company during their monthslong travels, and my aunt meant well, but sometimes her iron ways grated.

“Inez! ¿Dónde estás?” Elvira disappeared deeper into the garden, the sound of her voice getting lost between the palms.

I ignored her, my corset a lock around my rib cage, and clutched my pencil tighter. I squinted down at the illustration I’d finished. Mamá’s and Papá’s sketched faces stared up at me. I was a perfect blend of the two. I had my mother’s hazel eyes and freckles, her full lips and pointed chin. My father gave me his wild and curly black hair—now gone over to complete gray—and his tanned complexion, straight nose, and brows. He was older than Mamá, but he was the one who understood me the most.

Mamá was much harder to impress.

I hadn’t meant to draw them, hadn’t wanted to think of them at all. Because if I thought of them, I’d count the miles between us. If I thought of them, I’d remember they were a world away from where I sat hidden in a small corner

of the manor grounds.

I’d remember they were in Egypt.

A country they adored, a place they called home for half the year. For as long as I could remember, their bags were always packed, their goodbyes as constant as the rising and setting of the sun. For seventeen years, I sent them off with a brave smile, but when their exploring eventually stretched into months, my smiles had turned brittle.

The trip was too dangerous for me, they said. The voyage long and arduous. For someone who had stayed in one place for most of her life, their yearly adventure sounded divine. Despite the troubles they’d faced, it never stopped them from buying another ticket on a steamship sailing from the port of Buenos Aires all the way to Alexandria. Mamá and Papá never invited me along.

Actually, they forbade me from going.

I flipped the sheet with a scowl and stared down at a blank page. My fingers clutched the pencil as I drew familiar lines and shapes of Egyptian hieroglyphs. I practiced the glyphs whenever I could, forcing myself to remember as many as I could and their closest phonetic values to the Roman alphabet. Papá knew hundreds and I wanted to keep up. He always asked me if I’d learned any new ones and I hated disappointing him. I devoured the various volumes from Description de L’Egypte and Florence Nightingale’s journals while traveling through Egypt, to Samuel Birch’s History of Egypt. I knew the names of the pharaohs from the New Kingdom by heart and could identify numerous Egyptian gods and goddesses.

I dropped the pencil in my lap when I finished, and idly twisted the golden ring around my littlest finger. Papá had sent it in his last package back in July with no note, only his name and return address in Cairo labeled on the box. That was so like him to forget. The ring glinted in the soft light, and I remembered the first time I’d slipped it on. The moment I touched it, my fingers had tingled, a burning current had raced up my arm, and my mouth had filled with the taste of roses.

An image of a woman walked across my vision, disappearing when I blinked. In that breathless moment, I’d felt a keen sense of longing, the emotion acute, as if it were me experiencing it.

Papá had sent me a magic-touched object.

It was baffling.

I never told a soul what he did or what had happened. Old world magic had transferred onto me. It was rare, but possible as long as the object hadn’t been handled too many times by different people.

Papá once explained it to me like this: long ago, before people built their cities, before they decided to root themselves to one area, past generations of Spellcasters from all around the world created magic with rare plants and hard-to-find ingredients. With every spell performed, the magic gave up a spark, an otherworldly energy that was quite literally heavy. As a result, it would latch on to surrounding objects, leaving behind an imprint of the spell.

A natural byproduct of performing magic.

But no one performed it anymore. The people with the knowledge to create spells were long gone. Everyone knew it was dangerous to write magic down, and so their methods were taught orally. But even this tradition became a dead art, and so civilizations had to embrace man-made things.

Ancient practices were forgotten.

But all that created magic, that intangible something, had already gone somewhere. That magical energy had been sinking deep into the ground, or drowning itself in deep lakes and oceans. It clung to objects, the ordinary and obscure, and sometimes transferred whenever it first came into contact with something, or someone, else. Magic had a mind of its own, and no one knew why it leapfrogged, or clung to one object or person, but not the other. Regardless, every time a transfer happened, the spell weakened in minuscule degrees until it finally disappeared. Understandably, people hated picking up or buying random things that might hold old magic. Imagine getting ahold of a teapot that brewed envy or conjured up a prickly ghost.

Countless artifacts were destroyed or hidden by organizations specializing in magic tracing, and large quantities were buried and lost and mostly forgotten.

Much like the names of generations long past, or of the original creators of magic themselves. Who they were, how they lived, and what they did. They left all this magic behind—not unlike hidden treasures—most of which hadn’t been handled all that often.

Mamá was the daughter of a rancher from Bolivia, and in her small pueblo, she once told me, the magia was closer to the surface, easier to find. Trapped in plaster or worn leather sandals, an old sombrero. It had thrilled

her, the remnants of a powerful spell now caught up in the ordinary. She loved the idea of her town descending from generations of talented Spellcasters.

I flipped the page of my sketchbook and started again, trying not to think about The Last Letter I’d sent to them. I’d written the greeting in shaky hieratic—cursive hieroglyphic writing—and then asked them again to please let me come to Egypt. I had asked this same question in countless different ways, but the answer was always the same.

No, no, no.

But maybe this time, the answer would be different. Their letter might arrive soon, that day, and maybe, just maybe, it would have the one word I was looking for.

Yes, Inez, you may finally come to the country where we live half our lives away from you. Yes, Inez, you can finally see what we do in the desert, and why we love it so much—more than spending time with you. Yes, Inez, you’ll finally understand why we leave you, again and again, and why the answer has always been no.

Yes, yes, yes.

“Inez,” cousin Elvira yelled again, and I startled. I hadn’t realized she’d drawn closer to my hiding place. The magic clinging to the old tub might obscure my frame from afar but if she got close enough, she’d see me easily. This time her voice rose and I noted the hint of panic. “You’ve a letter!”

I snapped my face away from my sketch pad and sat up with a jerk.

Finalmente.

I tucked the pencil behind my ear, and climbed out of the tub. Swinging the heavy wooden door open a crack, I peered through, a sheepish smile on my face. Elvira stood not ten paces from me. Thankfully, Amaranta was nowhere in sight. She’d cringe at the state of my wrinkled skirt and report my heinous crime to her mother.

“Hola, prima!” I screamed.

Elvira shrieked, jumping a foot. She rolled her eyes. “You’re incorrigible.”

“Only in front of you.” I glanced down at her empty hands, looking for the missive. “Where is it?”

“My mother bid me to come fetch you. That’s all I know.”

We set off the cobbled path leading up to the main house, our arms linked. I walked briskly as was my norm. I never understood my cousin’s slow amble. What was the point in not reaching where you wanted to go quickly? Elvira hastened her step, following at my heels. It was an accurate picture of our relationship. She was forever trying to tag along. If I liked the color yellow, then she declared it the prettiest shade on earth. If I wanted carne asada for dinner, then she was already sharpening the knives.

“The letter won’t suddenly disappear,” Elvira said with a laugh, tossing her dark brown

hair. Her eyes were warm, her full mouth stretched into a wide grin. We favored each other in appearances, except for our eyes. Hers were greener than my ever-changing hazel ones. “My mother said it was postmarked from Cairo.”

My heart stuttered.

I hadn’t told my cousin about The Last Letter. She wouldn’t be happy about my wanting to join Mamá and Papá. Neither of my cousins nor my aunt understood my parents’ decision to disappear for half the year to Egypt. My aunt and cousins loved Buenos Aires, a glamorous city with its European-style architecture and wide avenues and cafés. My father’s side of the family hailed from Spain originally, and they came to Argentina nearly a hundred years ago, surviving a harrowing journey but ultimately making a success in the railroad industry.

Their marriage was a match built on combining Mamá’s good name and Papá’s great wealth, but it bloomed into mutual admiration and respect over the years, and by the time of my birth, into deep love. Papá never got the large family he wanted, but my parents often liked to say that they had their hands full with me anyway.

Though I’m not precisely sure how they did when they were gone so much.

The house came into view, beautiful and expansive with white stones and large windows, the style ornate and elegant, reminiscent of a Parisian manor. A gilded iron fence caged us in, obscuring views of the neighborhood. When I was little, I used to hoist myself up to the top bar of the gate, hoping for a glimpse of the ocean. It remained forever out of sight, and I had to content myself with exploring the gardens.

But the letter might change everything.

Yes or no. Was I staying or leaving? Every step I took toward the house might be one step closer to a different country. Another world.

A seat at the table with my parents.

“There you are,” Tía Lorena said from the patio door. Amaranta stood next to her, a thick, leather-bound tome in one hand. The Odyssey. An intriguing choice. If I recalled correctly, the last classic she tried to read had bitten her finger. Blood had stained the pages and the magic-touched book escaped out the window, never to be seen again. Though sometimes I still heard yips and growls coming from the sunflower beds.

My cousin’s mint-green gown ruffled in the warm breeze, but even so, not a single hair dared to escape her pulled-back hairstyle. She was everything my mother wanted me to be. Her dark eyes stole over mine, and her lips twitched in disapproval when she took in my stained fingers. Charcoal pencils always left their mark, like soot.

“Reading again?” Elvira asked her sister.

Amaranta’s attention flickered to Elvira, and her expression softened. She reached forward and linked arms with her. “It’s a fascinating tale; I wish you would have stayed with me. I would have read my favorite parts to you.”

She never used that sweet tone with me.

“Where have you been? Never mind,” Tía Lorena said as I began to answer. “Your dress is dirty, did you know?”

The yellow linen bore wrinkles and frightful stains, but it was one of my favorites. The design allowed me to dress without the help of a maid. I’d secretly ordered several garments with buttons easy to access, which Tía Lorena detested. She thought it made the gowns scandalous. My poor aunt

tried her hardest to keep me looking presentable but unfortunately for her, I had a singular ability to ruin hemlines and crush ruffles. I did love my dresses, but did they have to be so delicate?

I noticed her empty hands and smothered a flare of impatience. “I was in the garden.”

Elvira tightened her hold on my arm with her free one, and rushed to my defense. “She was practicing her art, Mamá, that’s all.”

My aunt and Elvira loved my illustrations (Amaranta said they were too juvenile), and always made sure I had enough supplies to paint and sketch. Tía Lorena thought I was talented enough to sell my work in the many galleries popping up in the city. She and my mother had quite the life planned out for me. Along with the lessons from countless tutors in the artistic sphere, I had been schooled in French and English, the general sciences, and histories, with a particular emphasis, of course, on Egypt.

Papá made sure I read the same books on that subject as he did, and also that I read his favorite plays. Shakespeare was a particular favorite of his, and we quoted the lines to each other back and forth, a game only we knew how to win. Sometimes we put on performances for the staff, using the ballroom as our own home theater. Since he was a patron of the opera house, he constantly received a steady supply of costumes and wigs and theater makeup, and some of my favorite memories were of us trying on new ensembles, planning for our next show.

My aunt’s face cleared. “Well, come along, Inez. You have a visitor.”

I shot a questioning look at Elvira. “I thought you said I had a letter?”

“Your visitor has brought a letter from your parents,” Tía Lorena clarified. “He must have run into them during his travels. I can’t think of who else might be writing to you. Unless there’s a secret caballero I don’t know about…” She raised her brows expectantly.

“You ran off the last two.”

“Miscreants, the both of them. Neither could identify a salad fork.”

“I don’t know why you bother rounding them up,” I said. “Mamá has her mind made up. She thinks Ernesto would make me a suitable husband.”

Tía Lorena’s lips turned downward. “There’s nothing wrong with having options.”

I stared at her in amusement. My aunt would oppose a prince if my mother suggested it. They’d never gotten along. Both were too headstrong, too opinionated. Sometimes I thought my aunt was the reason my mother chose to leave me behind. She couldn’t stand sharing space with my father’s sister.

“I’m sure his family’s wealth is a point in his favor,” Amaranta said in her dry voice. I recognized that tone. She resented being married off, more than I did. “That’s the most important thing, correct?”

Her mother glared at her eldest daughter. “It is not, just because…”

I tuned out the rest of the conversation, closed my eyes, my breath lodged at the back of my throat. My parents’ letter was here, and I’d finally have an answer. Tonight I could be planning my wardrobe, packing my trunks, maybe even convincing Elvira to accompany me on the long journey. I opened my eyes in time to catch the little line appear between my cousin’s eyebrows.

“I’ve been waiting to hear from them,” I explained.

She frowned. “Aren’t you always waiting to hear from them?”

A fantastic point. “I asked them if I could join them in Egypt,” I admitted, darting a nervous glance toward my aunt.

“But … but, why?” Tía Lorena sputtered.

I linked my arms through Elvira’s and propelled us into the house. We were charmingly grouped, traversing the long stretch of the tiled hall, the three of us arm in arm, my aunt leading us like a tour guide.

The house boasted nine bedrooms, a breakfast parlor, two living rooms, and a kitchen rivaling that of the most elegant hotel in the city. We even had a smoking room but ever since Papá had purchased a pair of armchairs that could fly, no one had been inside. They caused terrible damage, crashing into the walls, smashing the mirrors, poking holes into the paintings. To this day, my father still lamented the loss of his two-hundred-year-old whiskey trapped in the bar cabinet.

“Because she’s Inez,” Amaranta said. “Too good for indoor activities like sewing or knitting, or any other task for respectable ladies.” She slanted a glare in my direction. “Your curiosity will get you in trouble one day.”

I dropped my chin, stung. I wasn’t above sewing or knitting. I disliked doing either because I was so terribly wretched at them.

“This is about your cumpleaños,” Elvira said. “It must be. You’re hurt that they won’t be here, and I understand. I do, Inez. But they’ll come back, and we’ll have a grand dinner to celebrate and invite all the handsome boys living in the barrio, including Ernesto.”

She was partly right. My parents were going to miss my nineteenth. Another year without them as I blew out the candles.

“Your uncle is a terrible influence on Cayo,” Tía Lorena said with a sniff. “I cannot comprehend why my brother funds so many of Ricardo’s outlandish schemes. Cleopatra’s tomb, for heaven’s sake.”

“¿Qué?” I asked.

Even Amaranta appeared startled. Her lips parted in surprise. We were both avid readers, but I was unaware that she had read any of my books on ancient Egypt.

Tía Lorena’s face colored slightly, and she nervously tucked an errant strand of brown hair shot with silver behind her ear. “Ricardo’s latest pursuit. Something silly I overheard Cayo discussing with his lawyer, that’s all.”

“About Cleopatra’s tomb?” I pressed. “And what do you mean by fund, exactly?”

“Who on earth is Cleopatra?” Elvira said. “And why couldn’t you have named me something

like that, Mamá? Much more romantic. Instead, I got Elvira.”

“For the last time, Elvira is stately. Elegant and appropriate. Just like Amaranta.”

“Cleopatra was the last pharaoh of Egypt,” I explained. “Papá talked of nothing else when they were here last.”

Elvira furrowed her brow. “Pharaohs could be … women?”

I nodded. “Egyptians were quite progressive. Though, technically, Cleopatra wasn’t actually Egyptian. She was Greek. Still, they were ahead of our time, if you ask me.”

Amaranta shot me a disapproving look. “No one did.”

But I ignored her and glanced pointedly at my aunt, raising my brow. Curiosity burned up my throat. “What else do you know?”

“I don’t have any more details,” Tía Lorena said.

“It sounds like you do,” I said.

Elvira leaned forward and swung her head around so that she could look at her mother across from me. “I want to know this, too, actually—”

“Well, of course you do. You’ll do whatever Inez says or wants,” my aunt muttered, exasperated. “What did I say about nosy ladies who can’t mind their own business? Amaranta never gives me this much trouble.”

“You were the one eavesdropping,” Elvira said. Then she turned to me, an eager smile on her lips. “Do you think your parents sent a package with the letter?”

My heart quickened as my sandals slapped against the tile floor. Their last letter came with a box filled with beautiful things, and in the minutes that it took to unpack everything, some of my resentment had drifted away as I stared at the bounty. Gorgeous yellow slippers with golden tassels, a rose-colored silk dress with delicate embroidery, and a whimsical outer robe in a riot of colors: mulberry, olive, peach, and a pale sea green. And that wasn’t all; at the bottom of the box I had found copper drinking cups and a trinket dish made of ebony inlaid with pearl.

I cherished every gift, every letter they mailed to me, even though it was half of what I sent to them. It didn’t matter. A part of me understood that it was as much as I’d ever get from them. They’d chosen Egypt, had given themselves heart, body, and soul. I had learned to live with whatever was left over, even if it felt like heavy rocks in my stomach.

I was about to answer Elvira’s question, but we rounded the corner and I stopped abruptly, my reply forgotten.

An older gentleman with graying hair and deep lines carved across the brow of his brown face waited by the front door. He was a stranger to me. My entire focus narrowed down to the letter clamped in the visitor’s wrinkled hands.

I broke free from my aunt and cousins and walked quickly toward him, my heart fluttering wildly in my ribs, as if it were a bird yearning for freedom. This was it. The reply I’d been waiting for.

“Señorita Olivera,” the man said in a deep baritone. “I’m Rudolpho Sanchez, your parents’ solicitor.”

The words didn’t register. My hands had already snatched the envelope. With trembling fingers, I flipped it over, bracing myself for their answer. I didn’t recognize the handwriting on the opposite side. I flipped the note again,

studying the strawberry-colored wax sealing the flap. It had the tiniest beetle—no, scarab—in the middle, along with words too distorted to be called legible.

“What are you waiting for? Do you need me to read it for you?” Elvira asked, looking over my shoulder.

I ignored her and hastily opened the envelope, my eyes darting to the smeared lettering. Someone must have gotten the paper wet, but I barely noticed because I finally realized what I was reading. The words swam across the paper as my vision blurred. Suddenly, it was hard to breathe, and the room had turned frigid.

Elvira let out a sharp gasp near my ear. A cold shiver skipped down my spine, an icy finger of dread.

“Well?” Tía Lorena prodded with an uneasy glance at the solicitor.

My tongue swelled in my mouth. I wasn’t sure I’d be able to speak, but when I did, my voice was hoarse, as if I’d been screaming for hours.

“My parents are dead.”

PART ONE

A WORLD AWAY

NOVEMBER 1884

For God’s sake, I couldn’t wait to get off this infernal ship.

I peered out the round window of my cabin, my fingers pressed against the glass as if I were a child swooning outside a bakery window craving alfajores and a vat of dulce de leche. Not one cloud hung in the azure sky over Alexandria’s port. A long wooden deck stretched out to meet the ship, a hand in greeting. The disembarking plank had been extended, and several of the crew swept in and out of the belly of the steamship, carrying leather trunks and round hatboxes and wooden crates.

I had made it to Africa.

After a month of traveling by boat, traversing miles of moody ocean currents, I’d arrived. Several pounds lighter—the sea hated me—and after countless nights of tossing and turning, crying into my pillow, and playing the same card games with my fellow travelers, I was really here.

Egypt.

The country where my parents had lived for seventeen years.

The country where they died.

I nervously twisted the golden ring. It hadn’t come off my finger in months. Bringing it felt like I’d invited my parents with me on the journey. I thought I’d feel their presence the minute I locked eyes with the coast. A profound sense of connection.

But it never came. It still hadn’t.

Impatience pushed me away from the window, forced me to pace, my arms flapping wildly. Up and down I walked, covering nearly every inch of my stately room. Nervous energy circled around me like a whirlwind. I shoved my packed trunks out of the way with my booted foot to clear a wider path. My silk purse rested on the narrow bed, and as I marched past, I pulled it toward me to grab my uncle’s letter once more.

The second sentence still killed me, still made my eyes burn. But I forced myself to read the whole thing. The subtle rocking of the ship made it hard, but despite the sudden lurch in my stomach, I gripped his note and reread it for the hundredth time, careful not to accidentally tear the paper in half.

July 1884

My dear Inez,

I hardly know where to begin, or how to write of what I must. Your parents went missing in the desert and have been presumed dead. We searched for weeks and found no trace of them.

I’m sorry. More sorry than I’ll ever be able to express. Please know that I am your servant and should you need anything, I’m only a letter away. I think it’s best you hold their funeral in Buenos Aires without delay, so that you may visit them whenever you wish. Knowing my sister, I have no doubt her spirit is back with you in the land of her birth.

As I’ve no doubt you are aware, I’m now your guardian, and administrator of the estate and your inheritance. Since you are eighteen, and by all accounts a bright young woman, I have sent a letter to the national bank of Argentina granting my permission for you to withdraw funds as you need them—within reason.

Only you, and myself, will have access to the money, Inez.

Be very careful with whom you trust. I took the liberty of informing the family solicitor of the present circumstances and I urge you to go to him should you need anything immediate. If I may, I recommend hiring a steward to oversee the household so that you may have time and space to grieve this terrible loss. Forgive me for this news, and I truly lament I can’t be there with you to share your grief.

Please send word if

you need anything from me.

Your uncle,

Ricardo Marqués

I slumped onto the bed and flopped backward with unladylike abandon, hearing Tía Lorena’s admonishing tone ringing in my ear. A lady must always be a lady, even when no one is watching. That means no slouching or cursing, Inez. I shut my eyes, pushing away the guilt I’d felt ever since leaving the estate. It was a hardy companion, and no matter how far I traveled, it couldn’t be squashed or smothered. Neither Tía Lorena nor my cousins had known of my plans to abandon Argentina. I could imagine their faces as they read the note I’d left behind in my bedroom.

My uncle’s letter had shattered my heart. I’m sure mine had broken theirs.

No chaperone. Barely nineteen—I’d celebrated in my bedroom by crying inconsolably until Amaranta knocked against the wall loudly—voyaging on my own without a guide or any experience, or even a personal maid to handle the more troublesome aspects of my wardrobe. I’d really done it now. But that didn’t matter. I was here to learn the details surrounding my parents’ disappearance. I was here to learn why my uncle hadn’t protected them, and why they had been out in the desert alone. My father was absentminded, true, but he knew better than to take my mother out for an adventure without necessary supplies.

I pulled at my bottom lip with my teeth. That wasn’t quite true, however. He could be thoughtless, especially when rushing from one place to another. Regardless, there were gaps in what I knew, and I hated the unanswered questions. They were an open door I wanted to close behind me.

I hoped my plan would work.

Traveling alone was an education. I discovered I didn’t like to eat alone, reading on boats made me ill, and I was terrible at cards. But I learned that I had a knack for making friends. Most of them were older couples, voyaging to Egypt because of the agreeable climate. At first, they balked at my being alone, but I was prepared for that.

I pretended to be a widow and had dressed accordingly.

My backstory grew more elaborate with each passing day. Married off far too young to an older caballero who could have been my grandfather. By the first week, I had most of the women’s sympathy, and the gentlemen approved of my desire to widen my horizons by vacationing abroad.

I glanced at the window and scowled. With an impatient shake of my head, I pulled my cabin door open and peered up and down the corridor. Still no progress on disembarking. I shut the door and resumed pacing.

My thoughts turned to my uncle.

I’d mailed a hastily written letter to him after purchasing my ticket. No doubt he waited for me on the dock, impatient to see me. In a matter of hours, we’d be reunited after ten years. A decade without speaking. Oh, I had included

drawings to him in my letters to my parents every now and then, but I was only being polite. Besides, he never sent anything to me. Not one letter or birthday card or some small trinket tucked into my parents’ luggage. We were strangers, family in name and blood only. I barely remembered his visit to Buenos Aires, but that didn’t matter because my mother had made sure I never forgot her favorite brother, never mind that he was the only one she had.

Mamá and Papá were fantastic storytellers, spinning words into tales, creating woven masterpieces that were immersive and unforgettable. Tío Ricardo seemed larger than life. A mountain of a man, always carting around books, and adjusting his thin, wire-framed glasses, his hazel eyes pinned to the horizon, and wearing down yet another pair of boots. He was tall and brawny, at odds with his academic passions and scholarly pursuits. He thrived in academia, quite at home in a library, but was scrappy enough to survive a bar fight.

Not that I personally knew anything about bar fights or how to survive them.

My uncle lived for archaeology, his obsession beginning at Quilmes in northern Argentina, digging with the crew and wielding a shovel when he was my age. After he’d learned all that he could, he left for Egypt. It was here he fell in love and married an Egyptian woman named Zazi, but after only three years together, she and their infant daughter died during childbirth. He never remarried or came back to Argentina, except for that one visit. What I didn’t understand was what he actually did. Was he a treasure hunter? A student of Egyptian history? A lover of sand and blistering days out in the sun?

Maybe he was a little of everything.

All I really had was this letter. Twice he wrote that if I ever needed anything, I only had to let him know.

Well, I did need something, Tío Ricardo.

Answers.

Tío Ricardo was late.

I stood on the dock, my nose full of briny sea air. Overhead, the sun bore down in a fiery assault, the heat snatching my breath. My pocket watch told me I’d been waiting for two hours. My trunks were piled precariously next to me as I searched for a face that closely resembled my mother’s. Mamá told me her brother’s beard had gotten out of hand, bushy and streaked with gray, too long for polite society.

People crowded around me, having just disembarked, chattering loudly, excited to be in the land of majestic pyramids and the great Nile River bisecting Egypt. But I felt none of it, too focused on my sore feet, too worried about my situation.

A fissure of panic curled around my edges.

I couldn’t stay out here much longer. The temperature was turning cool as the sun marched across the sky, the breeze coming from the water had teeth to it, and I still had miles to go yet. From what I could remember, my parents would

board a train in Alexandria, and around four hours later, they’d reach Cairo. From there they’d hire transport to Shepheard’s Hotel.

My gaze dropped to my luggage. I contemplated what I could and couldn’t leave behind. Lamentably, I wasn’t strong enough to carry everything with me. Perhaps I could find someone to help, but I didn’t know the language beyond a few conversational phrases, none of which amounted to Hello, can you please assist me with all of my belongings? ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...