UNO

ONE YEAR LATER

Underneath my feet, the dragon waits.

Almost unconsciously, my attention drifts to the cobbled ground. I picture the dungeon below this tunnel, the horrid damp smell, the shadows crowding the corners and swift turns, and the row of cages where the monsters are kept under lock and key. In my mind, the beast moves restlessly in its cell, waiting for the moment the iron bars lift so it can bolt into the arena, searching for flesh, for a glimpse of the color red. The image incites a riot in my blood.

The trapped air inside the tunnel glides down my throat, fills my belly. When I exhale, some of the fear goes with it. My mind clears as I quicken my steps, following the curved wall made of craggy stone.

I have minutes before my flamenco routine.

La Giralda’s iron bell triumphantly heralds the start of our five hundredth anniversary show, and the sound carries to every corner of Santivilla and sinks into my skin, rattling bone. It’s a siren’s call, promising the best entertainment you’ll see all week, for the not-so-bargain price of twenty-seven reales. Outside the arena, there’s a long line curling around the building of those keen on still entering.

But there’s not an empty seat left in our dragon ring.

We’re the best at what we do, a set of familial skills passed down for centuries. Papá is descended from a long line of Dragonadores, famous for their courage in the ring. This building made of stone and brick and sweat is in my blood. The most prized possession belonging to the Zalvidar name, and one day it will be mine.

I walk along the underbelly of the ring, my wooden heels slapping against the stone corridor that leads to the arena, famous for its white sand that glitters under the sun. It’s brought in from the coast, carted on dozens of wagons pulled by several pairs of oxen, an effort well worth its price. There’s nothing quite like the look of spilled blood against something so pure.

My tomato-red flamenco dress swishes around my ankles, and I run my fingers along the craggy walls. I approach the entrance, and the roar of the crowd booms loud and insatiable. The sound skips down my spine, and a pleasant shiver dances across my skin. I almost forget about the dragon waiting to be unleashed.

Almost, but not quite.

Lola Delgado gently nudges me. “Are you worried about the dragon, the dance, or both?” She tugs impatiently at her wild dark hair. Lola gives up stuffing loose tendrils into her bun with a sigh. The light from the torches casts flickering shadows across her deeply tanned skin. She narrows her hazel eyes at me, understanding the reason behind the tight set to my mouth and why my knuckles turn white around my mother’s painted fan.

“It was one of my mother’s newest routines. An instant classic.”

Lola’s a head shorter than me, but even so, she manages to curl a protective arm around my shoulders. “The crowd will love you. They always do.” She drops her voice to a whisper. “Even if you perform one of your dance routines.”

She’s willfully forgetting about the last time I tried to do one of my own creations. The crowd was expecting to see a traditional routine of my mother’s, but I gave them one of mine. It still unsettles me—how quickly their cheers turned into disappointed shouting and insults.

I had finished the moves with my chin held high, even though I wanted to lie down on the hot sand and cover my ears so I couldn’t hear their yelling. I’ve never forgotten how little the people of Santivilla think of me.

But what truly destroyed me that day was the bitter gleam of sadness in Papá’s eyes, his thin smile that told me that even he wasn’t interested in seeing anything but my mother’s routines.

“They want Eulalia Zalvidar.” People want her brilliance on the dance floor, the luring sway of her hips, the way she could make you feel bold and inspired, all from watching her stamp across the stage. This is why I dance steps that belonged to her first.

She frowns. “Zarela…”

“It’s fine.” I straighten away from her, ears straining to hear the music that’ll signal my entrance. “Estoy bien, no te preocupes.”

“I do worry about you,” she says. “And it’s not fair. You’re the responsible one.”

“Just tell me I look presentable.” I lift up the skirt, letting the ruffles skim my ankles. “How does the dress look?”

She reaches forward and rearranges the collar so the pleats lay flat. As one of the maids of the household, she’s responsible for making sure I look the part. “Estás guapísima.”

“Thanks to you,” I say with a small smile.

She grins and her round cheeks flush prettily. Anytime we talk about clothing, her eyes light up. Had her circumstances been different, she could have apprenticed at the Gremio de los Sastres, the guild of tailors and textile workers, but her family couldn’t afford to send her. Now she works alongside our housekeeper, Ofelia, helping with the cooking and cleaning. But over the years, I’ve hired her to design and sew new dresses for my flamenco routines.

Her talent ought not to be wasted on dirty linens.

“Oh, I know I did a fabulous job with the alterations.”

“Your humility moves me.”

She continues as if I haven’t spoken. “And that dress is doing marvelous things for your—”

I narrow my gaze. “Let me stop you right there.”

“What? I was only trying to say that the fabric drapes in all the right—”

“Lola.”

She winks at me, and I resist hitting her with my mother’s fan. She’s trying to distract me, but my nerves roar to life despite her outrageous flattery. The crowd’s cheering is insistent, demanding to be entertained like a child. The sound envelops us in a fiery rush. Lola winces. I lean forward, unable to keep the smirk off my face. “Did we drink a little too much manzanilla last night? The sherry always gives you a headache.”

“Ugh,” she mumbles. “I resent your horrid, smug tone. To think I came down here to make sure you were fine—” She breaks off, swaying on her feet.

“You came down here to see Guillermo,” I cut in with an arched brow. “Admit it.”

She looks away, biting her lip.

“What happened to Rosita?”

Lola rolls her eyes. “She was too wild.”

“But you’re wild,” I say laughingly.

“Exactly. I can barely take care of myself. I’m too young to worry about anyone else.”

I gently push her behind me, as I desperately fight a laugh. “You’re a menace. Go find a seat.”

“If you see him,” she says with a sly smile. “Tell him I like the way his pants fit.”

“I will never say such nonsense to him or anyone, ever.”

“What?” she asks innocently. “He’s entirely too handsome for someone so studious. Someone ought to let him know.”

Personally, I don’t understand Guillermo’s appeal. As a member of the Gremio de Magia, he spends most of his day bent over chopped-up dragon parts: pulled-out teeth, sawed-off ivory horns, and eyeballs stored in vats of oil. Guillermo is here now, somewhere in the arena, waiting for Papá to kill today’s monster so that he can pay for the remains and take them back to the Gremio in order to concoct more potions.

“I’ll tell him you say hello,” I say finally.

“That doesn’t sound like me in the slightest.”

“I’m not going to do your flirting for you. Not even if you ask nicely.”

Lola pouts and then stumbles away, and I let out a little laugh. I turn back around. I have to concentrate on my performance and not think of anything other than the steps and the music. I focus on my breath as it catches in my throat, and on my body coiled tight and ready for the show.

The entrance is an arched doorway, lined with cobblestone in varying hues of clay and the tawny sand outside the walled city of Santivilla. On the other side, patrons wave their sombreros in the air as they catch a glimpse of me, dressed as my unforgettable mother, wearing her flamenco dress and shoes. The outfit is endlessly bold, with ruffles adorning the off-shoulder neckline and hem. Lola altered the costume to fit my smaller frame perfectly.

But while I may style my black hair like she did, wear the same color rouge on my lips, and line my eyes in charcoal the way she liked, I am not my mother. I am the forgettable village next to her metropolis.

What she did was miraculous. I merely worship at the same altar.

Nerves grip my heart and squeeze. It’s always this way before I take the stage. I’m holding up my father’s name and my mother’s legacy. I inhale deeply, allowing the crowd’s cheering and sharp whistling and the sounds of the strumming guitar coming from the center of the ring to remind me of who I am: Zarela Zalvidar, daughter of the best performers in all of Hispalia.

I damn well better act like it.

This is the most important show we’ll ever put on, our five hundredth anniversary spectacle, covered by the national paper, Los Tiempos, and watched by wealthy patrons and prominent guild members from all over Hispalia. They’ve come with their velvet drawstring purses, lofty connections, and dreams of being entertained extravagantly in a city as beautiful as it is dangerous.

The crowd hushes at the sight of the guitarist settling onto his stool above the platform. Pressure builds in my chest. My shoulders are tight, and I roll each side. I inhale again, holding air captive deep in my lungs. I exhale, and I imagine my fear riding my breath, leaving me behind. I throw my shoulders back, my spine straight and proud like La Giralda’s bell tower, and I march toward the raised wooden platform in the middle of the arena, arms outstretched to meet the hundreds of spectators sitting around the ring. I keep my chin lifted high, and my grin wide enough for everyone to see. Five hundred spectators stomp their feet to the rhythm of the guitar, clapping their hands at a fast clip.

Ra-ta-ta-ta-ta-tat.

It’s a drug, that dizzying rush as people scream louder, wanting a part of me. Papá stands at the other designated entrance for performers, with a gleaming smile. He’s with his childhood friend, Tío Hector, a fellow Dragonador who owns a popular dragon ring across town. He’s not really my uncle, but I’ve always called him one for as long as I can remember.

The throng hushes. I close my eyes and wait for the beat. When I find it, I slowly stomp on the stage. The soles of my black leather shoes smack against the wood like a battering ram. The sound is the base of my performance, and the noise anchors me to my mother.

I sway my hips as the guitarist strums faster and faster, fingers moving quickly up and down the instrument. I spin and twirl, bending backward as I whip out my fan, flinging it open with a snap. The cheering starts anew, and I smile as I stomp and clap along to the rhythm of the music. I lay my fears to rest. In this moment, I relish the dance and the way the music glides along my body as I position my legs and torso into strong lines.

Grief has made me a better dancer. I command the stage and offer this tribute to Mamá, to her adoring fans who scream her name even now. It’s why I’ve stopped Papá from introducing me ahead of my performance.

The song ends at a slow crawl, and I move with the dying notes, bending forward in a traditional Hispalian bow. Sweat slides down the back of my neck, and my breath comes out in great huffs. Every dance is a fight against the ground, and my legs shake from the effort to win. Flowers rain, dropping dead at my feet. I straighten, wave at the patrons and their fat purses, and sashay to Papá and Hector where they wait by the second tunnel entrance, quietly proud. Papá carries an enormous bouquet of gardenias, the stems tied tightly with a gold ribbon, fluttering in the breeze like a banner beckoning me home. I take the flowers as Hector leans forward to fix the adornment in my hair, smiling broadly.

Papá curls a strong arm around my waist. “Preciosa. Just like your querida mamá.”

He studies my face, searching for my mother in the curve of my cheek and the fire in my eyes. But I’m not her. I can’t say the words out loud—he’d be crushed, so instead, I say what he needs. “Para Mamá. So we never forget her.”

A small smile tiptoes across his face, but I’m not fooled. He might convince a stranger that he’s happy, but I’ve seen what a real smile looks like, and that’s not it, though I’ve grown accustomed to this version.

Hector guides me backward, farther into the tunnel where the white sand no longer covers the ground. He yanks on a pocket iron bar door, dragging it forward until it slides into the gap on the opposite wall. Papá remains on the other side, closest to the arena. I reach between the slots, wanting Papá’s hand. I try to remain calm, remind myself that my father is the best Dragonador in all of Hispalia.

But the risk never fades.

Any fight could be his last.

Last week, a dragon wearing ribbons and a necklace made of flowers gored a fighter in the stomach in one of our rival’s arena. The man had died in front of hundreds, including his wife and two small children.

Papá strides to the center of the arena where the stage has already been removed, and all that’s left is the hot sand. His snug jacket encloses his strong arms, and his patent leather shoes are polished to a resplendent sheen. The ensemble he wears is startling white, stitched with red thread and adorned by a thousand beads in a burst of chaotic color, handmade and designed by Lola. It had taken her months of painstakingly sewing each sparkling piece onto the Dragonador costume, known everywhere in Hispalia as the traje de luces—suit of lights.

His broad shoulders are proud and straight enough to measure with, and his hands grip the golden handle of the red banner that bears our family name. Every step Papá takes adds flair and drama to the fight. He is a consummate entertainer and charmer. Born to please and impress. Passionate, quick to anger, and fiercely loyal.

In the arena, he is the most like the Papá I remember.

The lone iron gate rises. The crowd sits, quiet and expectant. Hundreds of fans open and snap in the sweltering heat, fluttering like bird wings. My heart thuds painfully and Hector pats my arm reassuringly.

“He’ll be fine,” he murmurs.

I barely hear him. From within another dark tunnel—there are three leading out of the arena—the Morcego races forward like an enraged bull. Its ebony body shines bright, glowing with energy. Two ivory tusks trailing golden ribbons protrude from its toothy mouth, and its eyes are bright yellow and mesmerizing. Around its neck are flowers, fluttering delicately against the scales that are stronger than armor.

I can’t take my gaze off the beast.

I clutch at the cobbled tunnel wall of the arena entrance, fingers digging into the grooves. My chest is on fire, rising and falling too fast. The dress is a fist around my heart.

Hector leans close. “Zarela?”

I nod and breathe deeply, fighting to regain my composure. The dragon is wider and taller than Papá, but there’s determination in the flat line of his mouth. He’s never feared them. I thought he’d turn away from dragonfighting after Mamá died, but her death only made him angry. Instead of one show a month, we now host two. I worry Papá won’t stop fighting until all the dragons of Hispalia have been hunted down and dragged in front of him.

The dragon snaps its great jaws and rushes forward, shiny claws digging into the sand. Papá sidesteps the attack, and the capote’s fabric curls around the wind like a beckoning finger. The beast’s attention is on the red flash of cloth, and Papá knows it. He pulls a long, thin blade with his free hand, while launching the banner high into the air. The dragon jumps, jaws snapping, trying to reach for it. But its wings have been clipped, and it can only jump so high. The Morcego lands on the ground with a furious roar, and as the dust rises and then settles, Papá makes his move.

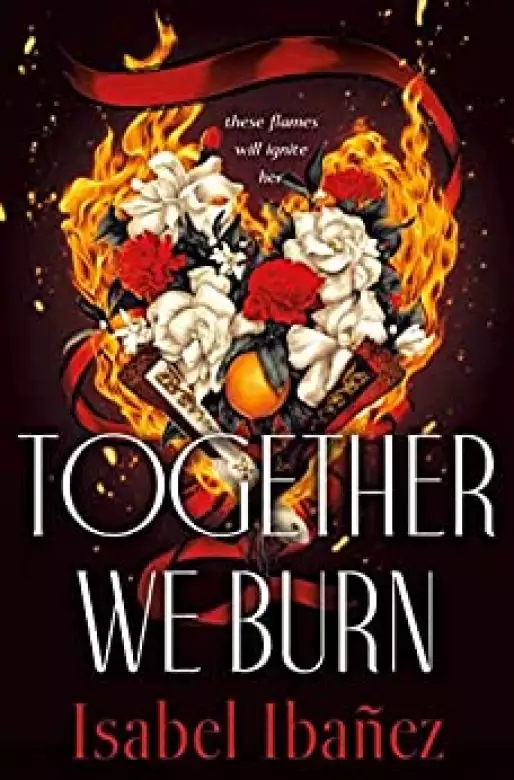

Copyright © 2022 by Isabel Ibañez

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved