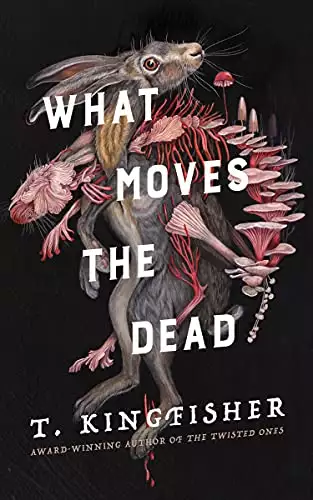

The mushroom’s gills were the deep-red color of severed muscle, the almost-violet shade that contrasts so dreadfully with the pale pink of viscera. I had seen it any number of times in dead deer and dying soldiers, but it startled me to see it here.

Perhaps it would not have been so unsettling if the mushrooms had not looked so much like flesh. The caps were clammy, swollen beige, puffed up against the dark-red gills. They grew out of the gaps in the stones of the tarn like tumors growing from diseased skin. I had a strong urge to step back from them, and an even stronger urge to poke them with a stick.

I felt vaguely guilty about pausing in my trip to dismount and look at mushrooms, but I was tired. More importantly, my horse was tired. Madeline’s letter had taken over a week to reach me, and no matter how urgently worded it had been, five minutes more or less would not matter.

Hob, my horse, was grateful for the rest, but seemed annoyed by the surroundings. He looked at the grass and then up at me, indicating that this was not the quality to which he was accustomed.

“You could have a drink,” I said. “A small one, perhaps.”

We both looked into the water of the tarn. It lay dark and very still, reflecting the grotesque mushrooms and the limp gray sedges along the edge of the shore. It could have been five feet deep or fifty-five.

“Perhaps not,” I said. I found that I didn’t have much urge to drink the water either.

Hob sighed in the manner of horses who find the world not to their liking and gazed off into the distance.

I looked across the tarn to the house and sighed myself.

It was not a promising sight. It was an old gloomy manor house in the old gloomy style, a stone monstrosity that the richest man in Europe would be hard-pressed to keep up. One wing had collapsed into a pile of stone and jutting rafters. Madeline lived there with her twin brother, Roderick Usher, who was nothing like the richest man in Europe. Even by Ruravia’s small, rather backward standards, the Ushers were genteelly impoverished. By the standards of the rest of Europe’s nobility, they were as poor as church mice, and the house showed it.

There were no gardens that I could see. I could smell a faint sweetness in the air, probably from something flowering in the grass, but it wasn’t enough to dispel the sense of gloom.

“I shouldn’t touch that if I were you,” called a voice behind me.

I turned. Hob lifted his head, found the visitor as disappointing as the grass and the tarn, and dropped it again.

She was, as my mother would say, “a woman of a certain age.” In this case, that age was about sixty. She was wearing men’s boots and a tweed riding habit that may have predated the manor.

She was tall and broad and had a gigantic hat that made her even taller and broader. She was carrying a notebook and a large leather knapsack.

“Pardon?” I said.

“The mushroom,” she said, stopping in front of me. Her accent was British but not London—somewhere off in the countryside, perhaps. “The mushroom, young…” Her gaze swept down, touched the military pins on my jacket collar, and I saw a flash of recognition across her face: Aha!

No, recognition is the wrong term. Classification, rather. I waited to see if she would cut the conversation short or carry on.

“I shouldn’t touch it if I were you, officer,” she said again, pointing to the mushroom.

I looked down at the stick in my hand, as if it belonged to someone else. “Ah—no? Are they poisonous?”

She had a rubbery, mobile face. Her lips pursed together dramatically. “They’re stinking redgills. A. foetida, not to be confused with A. foetidissima—but that’s not likely in this part of the world, is it?”

“No?” I guessed.

“No. The foetidissima are found in Africa. This one is endemic to this part of Europe. They aren’t poisonous, exactly, but—well—”

She put out her hand. I set my stick in it, bemused. Clearly a naturalist. The feeling of being classified made more sense now. I had been categorized, placed into the correct clade, and the proper courtesies could now be deployed, while we went on to more critical matters like mushroom taxonomy.

“I suggest you hold your horse,” she said. “And perhaps your nose.” Reaching into her knapsack, she fished out a handkerchief, held it to her nose, and then flicked the stinking redgill mushroom with the very end of the stick.

It was a very light tap indeed, but the mushroom’s cap immediately bruised the same visceral red-violet as the gills. A moment later, we were struck by an indescribable smell— rotting flesh with a tongue-coating glaze of spoiled milk and, rather horribly, an undertone of fresh-baked bread. It wiped out any sweetness to the air and made my stomach lurch.

Hob snorted and yanked at his reins. I didn’t blame him. “Gahh!”

“That was a little one,” said the woman of a certain age. “And not fully ripe yet, thank heavens. The big ones will knock your socks off and curl your hair.” She set the stick down, keeping the handkerchief over her mouth with her free hand. “Hence the ‘stinking’ part of the common name. The ‘redgill,’ I trust, is self-explanatory.”

“Vile!” I said, holding my arm over my face. “Are you a mycologist, then?”

I could not see her mouth through the handkerchief, but her eyebrows were wry. “An amateur only, I fear, as supposedly befits my sex.”

She bit off each word, and we shared a look of wary understanding. England has no sworn soldiers, I am told, and even if it had, she might have chosen a different way. It was none of my business, as I was none of hers. We all make our own way in the world, or don’t. Still, I could guess at the shape of some of the obstacles she had faced.

“Professionally, I am an illustrator,” she said crisply. “But the study of fungi has intrigued me all my life.”

“And it brought you here?”

“Ah!” She gestured with the handkerchief. “I do not know what you know of fungi, but this place is extraordinary! So many unusual forms! I have found boletes that previously were unknown outside of Italy, and one Amanita that appears to be entirely new. When I have finished my drawings, amateur or no, the Mycology Society will have no choice but to recognize it.”

“And what will you call it?” I asked. I am delighted by obscure passions, no matter how unusual. During the war, I was once holed up in a shepherd’s cottage, listening for the enemy to come up the hillside, when the shepherd launched into an impassioned diatribe on the finer points of sheep breeding that rivaled any sermon I have ever heard in my life. By the end, I was nodding along and willing to launch a crusade against all weak, overbred flocks, prone to scours and fly-strike, crowding out the honest sheep of the world.

“Maggots!” he’d said, shaking his finger at me. “Maggots ’n piss in t’ flaps o’ they hides!”

I think of him often.

“I shall call it A. potteri,” said my new acquaintance, who fortunately did not know where my thoughts were trending. “I am Eugenia Potter, and I shall have my name writ in the books of the Mycology Society one way or another.”

“I believe that you shall,” I said gravely. “I am Alex Easton.” I bowed.

She nodded. A lesser spirit might have been embarrassed to have blurted her passions aloud in such a fashion, but clearly Miss Potter was beyond such weaknesses—or perhaps she simply assumed that anyone would recognize the importance of leaving one’s mark in the annals of mycology.

“These stinking redgills,” I said, “they are not new to science?”

She shook her head. “Described years ago,” she said. “From this very stretch of countryside, I believe, or one near to it. The Ushers were great supporters of the arts long ago, and one commissioned a botanical work. Mostly of flowers”—her contempt was a glorious thing to hear—“but a few mushrooms as well. And even a botanist could not overlook A. foetida. I fear that I cannot tell you its common name in Gallacian, though.”

“It may not have one.”

If you have never met a Gallacian, the first thing you must know is that Gallacia is home to a stubborn, proud, fierce people who are also absolutely piss-poor warriors. My ancestors roamed Europe, picking fights and having the tar beaten out of them by virtually every other people they ran across. They finally settled in Gallacia, which is near Moldavia and even smaller. Presumably they settled there because nobody else wanted it. The Ottoman Empire didn’t even bother to make us a vassal state, if that tells you anything. It’s cold and poor and if you don’t die from falling in a hole or starving to death, a wolf eats you. The one thing going for it is that we aren’t invaded often, or at least we weren’t, until the previous war.

In the course of all that wandering around losing fights, we developed our own language, Gallacian. I am told it is worse than Finnish, which is impressive. Every time we lost a fight, we made off with a few more loan words from our enemies. The upshot of all of this is that the Gallacian language is intensely idiosyncratic. (We have seven sets of pronouns, for example, one of which is for inanimate objects and one of which is used only for God. It’s probably a miracle that we don’t have one just for mushrooms.)

Miss Potter nodded. “That is the Usher house on the other side of the tarn, if you were curious.”

“Indeed,” I said, “it is where I am headed. Madeline Usher was a friend of my youth.”

“Oh,” said Miss Potter, sounding hesitant for the first time. She looked away. “I have heard she is very ill. I am sorry.”

“It has been a number of years,” I said, instinctively touching the pocket with Madeline’s letter tucked into it.

“Perhaps it is not so bad as they say,” she said, in what was undoubtedly meant to be a jollying tone. “You know how bad news grows in villages. Sneeze at noon and by sundown the gravedigger will be taking your measurements.”

“We can but hope.” I looked down again into the tarn. A faint wind stirred up ripples, which lapped at the edges. As we watched, a stone dropped from somewhere on the house and plummeted into the water. Even the splash seemed muted.

Eugenia Potter shook herself. “Well, I have sketching to do. Good luck to you, Officer Easton.”

“And to you, Miss Potter. I shall look forward to word of your Amanitas.”

Her lips twitched. “If not the Amanitas, I have great hopes for some of these boletes.” She waved to me and strode out across the field, leaving silver boot prints in the damp grass. I led Hob back to the road, which skirted the edge of the lake. It was a joyless scene, even with the end of the journey in sight. There were more of the pale sedges and a few dead trees, too gray and decayed for me to identify. (Miss Potter presumably knew what they were, although I would never ask her to lower herself to identifying mere vegetation.) Mosses coated the edges of the stones and more of the stinking redgills pushed up in obscene little lumps. The house squatted over it like the largest mushroom of them all.

My tinnitus chose that moment to strike, a high-pitched whine ringing through my ears and drowning out even the soft lapping of the tarn. I stopped and waited for it to pass. It’s not dangerous, but sometimes my balance becomes a trifle questionable, and I had no desire to stumble into the lake. Hob is used to this and waited with the stoic air of a martyr undergoing torture.

Sadly, while my ears sorted themselves out, I had nothing to look at but the building. God, but it was a depressing scene.

It is a cliché to say that a building’s windows look like eyes because humans will find faces in anything and of course the windows would be the eyes. The house of Usher had dozens of eyes, so either it was a great many faces lined up together or it was the face of some creature belonging to a different order of life—a spider, perhaps, with rows of eyes along its head.

I’m not, for the most part, an imaginative soul. Put me in the most haunted house in Europe for a night, and I shall sleep soundly and wake in the morning with a good appetite. I lack any psychic sensitivities whatsoever. Animals like me, but I occasionally think they must find me frustrating, as they stare and twitch at unknown spirits and I say inane things like “Who’s a good fellow, then?” and “Does kitty want a treat?” (Look, if you don’t make a fool of yourself over animals, at least in private, you aren’t to be trusted. That was one of my father’s maxims, and it’s never failed me yet.)

Given that lack of imagination, perhaps you will forgive me when I say that the whole place felt like a hangover.

What was it about the house and the tarn that was so depressing? Battlefields are grim, of course, but no one questions why. This was just another gloomy lake, with a gloomy house and some gloomy plants. It shouldn’t have affected my spirits so strongly.

Granted, the plants all looked dead or dying. Granted, the windows of the house stared down like eye sockets in a row of skulls, yes, but so what? Actual rows of skulls wouldn’t affect me so strongly. I knew a collector in Paris… well, never mind the details. He was the gentlest of souls, though he did collect rather odd things. But he used to put festive hats on his skulls depending on the season, and they all looked rather jolly.

Usher’s house was going to require more than festive hats. I mounted Hob and urged him into a trot, the sooner to get to the house and put the scene behind me.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved