- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

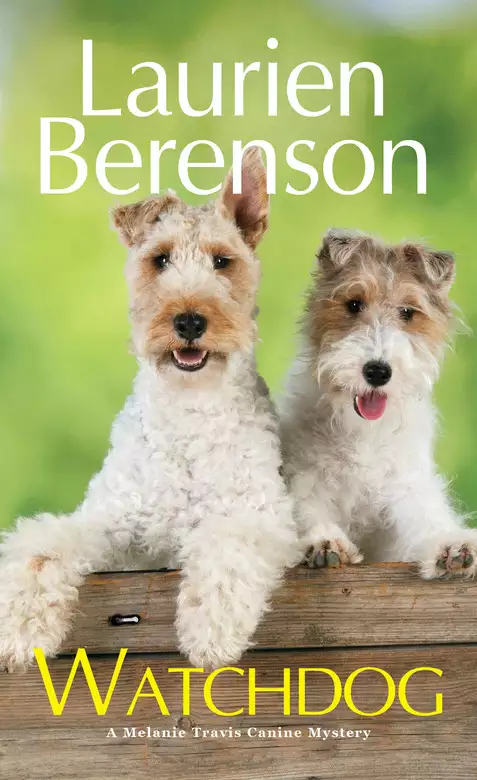

“Fresh, lively writing, a tough mystery, light humor, and insight into the peculiarities of human and canine behavior.”— Booklist It’s autumn in Connecticut. Melanie Travis has just started a new job, and with the added excitement of showing her Standard Poodle, Faith, in the fall shows, the last thing she wants is to become embroiled in yet another of her brother Frank’s moneymaking schemes. His current brainstorm—remaking an old store in stylish suburban Fairfield County into a trendy coffee bar—already has the neighbors snarling. Worse, wealthy Marcus Rattigan, who’s bankrolling the project, is found murdered on the premises, and the police think Frank did it. Always the family watchdog, and faced with Frank’s imminent arrest, Melanie has no choice but to take on the investigation. Drawing on her connections in the dog world, Melanie is soon successfully unmuzzling the dead man’s nearest and dearest, including a bitter ex-wife, spurned mistress, and ambitious second-in-command. But she’s about to learn that being a watchdog can be dangerous—especially when every clue leads her one step closer to a murderer desperate enough to kill again… “Berenson’s writing is as warm and fuzzy as the dogs.”— Publishers Weekly

Release date: March 18, 2013

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Watchdog

Laurien Berenson

So when my brother, Frank, came to me with his hand out, I didn’t have to think twice about what to say. I turned him down flat. Unfortunately, with Frank it’s never that easy.

“Trust me, Mel,” he said. “It’s the opportunity of a lifetime.”

The opportunity of his lifetime, maybe. Mine? I doubted it.

For more than a quarter century, ever since he was old enough to walk and talk, I’d watched my little brother maneuver himself into and out of tight spots. He was bright, charming, and impetuous. What he’d never been was practical.

That was my job apparently. I was the diligent big sister who, more often than not, had to stay behind and pick up the pieces when Frank dropped whatever he was doing and went barreling on to his next grand scheme.

“At least let me tell you what it’s about,” he said. “You can’t turn me down without giving me a fair shot.”

“Sure I can. Watch me. N-O.”

“I’m not listening.” Frank raised his hands and put them over his ears. “I can’t hear you.” With a maturity level like that, you can see why he would come to me rather than going to a bank.

I glared at him for a moment, but the effort was half-hearted. It was 8:30 on a weekday morning. In the normal way of things, I wouldn’t have expected my brother to be out of bed yet, much less across town and standing in my kitchen. He must have really thought this was important.

“You’ve got ten minutes,” I told him. “No more. Davey’s bus already picked him up and I was just on my way out the door. You’re not making me late for school.”

Davey was my son, six years old and filled with all the joy and wonder and mischief of his age. In short he was a great kid, at least in his mother’s eyes. He’d started first grade a month earlier and was delighted to be riding to school on the bus.

The year before, we’d commuted to Hunting Ridge Elementary together. I’d been employed there for the last six years as a special education teacher. Over the summer, however, I’d taken a new job at Howard Academy, a private school near downtown Greenwich. Four weeks into the school year, I was still trying to make a good impression.

“Relax.” Frank glanced at the clock over the sink. “You’ve got plenty of time.”

My brother is an expert at relaxing, probably because he gets so much practice. I was tempted to drum my fingers on the countertop.

People meeting us for the first time often comment that we look alike. Though we have many of the same features—straight brown hair, hazel eyes, and the strong jawline often associated with stubbornness—I’ve never been able to see the similarity. Maybe I don’t want to see it.

While I waited for Frank to get to the point, I walked to the back door and looked out. The small yard behind the house was enclosed, and Faith, Davey’s and my Standard Poodle, was having a last bit of exercise before I left for the day. When I opened the door, she raced across the short distance between us and bounded up the steps.

“That is one strange looking animal,” Frank said as Faith came sliding into the kitchen, did a quick turn on the linoleum floor, then jumped up and waved her front paws in the air waiting for the biscuit she knew I’d be holding.

I flipped the peanut butter tidbit into the air and watched Faith catch it on the fly. “Nine minutes. You know, most people hoping to borrow money from me wouldn’t start by insulting my dog.”

“With that hairdo? The comment wasn’t an insult, it was a statement of fact.”

All right, so Faith’s appearance was a little odd. It wasn’t my fault. At least, not entirely. She’d been a present from my Aunt Peg, a devoted Standard Poodle breeder whose Cedar Crest Kennel has produced a number of top winning Poodles over the years. Like her ancestors before her, Faith was a show dog.

Accordingly, her hair was being maintained in the continental clip, a modern descendant of an old German hunting trim, and one of only two clips adult Poodles were allowed to wear in the ring. Faith’s dense black coat was long and scissored into a rounded shape on the front half of her body. At the same time, most of her hindquarter had been clipped down to the skin. There were pompons over each of her hip bones and just above her feet on all four legs. A bigger pompon wagged at the end of her tail.

Because the topknot on her head was nearly a foot long and needed to be kept out of the way when she wasn’t in the ring, I’d sectioned the hair into a series of ponytails, which were held in place by brightly colored rubber bands. The long, thick fringe on her ears was protected by matching plastic wraps, which were doubled under and banded in place.

Standards are the biggest of the three varieties of Poodles. Faith is twenty-four inches at the shoulder, which means that she and Davey stand nearly eye to eye. Maybe that explains why they get along so well; or maybe it was just that kids and Standard Poodles are a great combination.

Faith also has wonderfully expressive dark brown eyes. Sometimes I could swear she knows exactly what I’m thinking. Like now, as she gazed at Frank with her head tipped to one side. No doubt she was wondering what he was doing there and why I hadn’t left for school yet. I reached down and gave her chin a scratch.

“Fine by me,” I said to Frank. “You want to discuss the dog’s trim, it’s your eight minutes.”

“Nine,” he said, probably hoping to impress me with his counting skills. “I’ve still got nine.”

I waved a hand. It wasn’t worth arguing.

Frank waited until I was still, then made his grand announcement. “I’m starting up my own business, Mel. This is your chance to get in on the ground floor.”

Probably just where I’d remain, too.

“What kind of business are you going into?”

It wasn’t an idle question. In the half decade since college, my brother has held a variety of jobs—everything from bartender to sales clerk to general handyman. If he had chosen a career path, I had yet to see the signs.

“I’m opening up a coffee bar. You know how popular they are. Everyone’s looking for a neighborhood hangout, and I’ve managed to secure a great location.”

From the sound of things, Frank was going to need every minute of the time I allotted him. I went back to the table and sat down. Faith hopped up and draped her front legs across my lap, then angled her head upward so her muzzle rested just below my shoulder.

As she settled in, I could feel the creases being pressed across the front of my skirt. Luckily I buy most of my clothes at Eddie Bauer and L.L. Bean, so they can take a few knocks. I burrowed my fingers through the Poodle’s thick coat and rubbed behind her ear.

“Where is it?”

“Right here in north Stamford. Remember Haney’s General Store out on Old Long Ridge Road?”

I nodded, picturing a small clapboard building with a wide porch and room for four or five cars to park out front. In the early fifties when the farms and open acreage of north Stamford were being developed into affordable housing to accommodate the post-war family boom, Mr. Haney had opened his small general store. It served as a convenience for harried mothers who hadn’t wanted to run all the way into town for a carton of eggs or a bottle of milk. In those days, he’d done a thriving business.

But as the city of Stamford continued to grow by leaps and bounds, supermarkets and strip malls had sprung up within easy reach of almost every shopper. Mr. Haney grew older and the wares that he stocked weren’t replenished nearly as often. It had been at least two years since I’d been to his store, and even then the building had begun to look run-down.

Signs covering the front windows advertising the weekly specials couldn’t disguise the fact that the glass needed a good cleaning. The red paint on the front door had faded to a musty pink. To top it off, the gallon of milk I’d purchased had been sour. I hadn’t been back since.

“Is he still in business?” I asked.

“Not anymore. That’s what I’m trying to tell you. As of last month, Mr. Haney retired and moved to Florida. I’m the new owner.”

“Owner?” That got my attention. “Frank, how could you afford to buy a building?”

“Maybe partial proprietor is a better term. I don’t exactly own the place.”

No surprise there.

“I have a long-term lease, and I’m doing renovations. Haney’s General Store is going to become Grounds For Appeal. By Christmas we’ll be ready for the grand opening.”

“Grounds For Appeal?” I frowned. “It sounds like a cut rate law office.”

“That’s not set in stone yet,” Frank said quickly. “I’m still working out some of the details. You could help. Like I said, things are just beginning to get moving. Now would be the perfect time for you to invest.”

“Why?”

“Why?” The question seemed to puzzle him. “Well, to be perfectly honest, because I could use some cash.”

As if I couldn’t have guessed. “Actually, Frank, I was wondering why you think this would be a good idea for me.”

“Because once the coffee bar gets up and running, I’m going to be making a ton of money. What kind of a brother would I be if I didn’t offer my only sister to have the chance to get in on it?”

“Solvent?” I ventured. I checked my watch. If I wasn’t out the door in five minutes max, I was going to miss the first bell. “Look, I don’t really have time to discuss this right now. And as you know perfectly well, I don’t have any extra money. At least not the kind you’re looking for.”

“You’ve got Bob.”

Bob was my ex-husband and Davey’s father. After a four-year absence from our lives, he’d shown up unexpectedly in the spring looking to get reacquainted with his son. At the same time, he’d reinstated the child support payments he was supposed to have been making all along.

Thanks to his contributions, Davey and I were a good deal better off than we had been. We’d been able to have the house painted and take a modest vacation over the summer. We were not, however, in any position to be looking for investments.

“Bob went home to Texas, Frank. He has a new wife there.”

“He also has an oil well.”

“That’s his money, not mine.”

“You could ask him for some.”

“I could,” I said, nudging Faith off my lap so I could stand. “But I’m not going to. Whatever you’ve gotten yourself into this time, you’re just going to have to take care of it without my help.”

“Okay, if that’s the way you want to be. Most people would jump at the chance to get into a deal with Marcus Rattigan, but if you’re not interested, I guess that’s your business.”

I was halfway to the door but I stopped and turned. “Marcus Rattigan? What do you have to do with him?”

“He’s the guy who bought the building. Didn’t I mention that?”

He knew perfectly well he hadn’t.

Marcus Rattigan was a local entrepreneur whose influence in the construction and development business was well documented in Fairfield County. Over the last decade more than a dozen apartment complexes had sprung up in surrounding towns, their signs sporting the familiar blue and gold logo of his Anaconda Properties.

Rattigan was known for buying up tracts of land, then bending local zoning laws to the breaking point in order to accommodate the greatest possible housing density. He supplied my newspaper with a steady stream of front page stories, and town officials in most municipalities kept a wary eye on the proceedings while fervently wishing him elsewhere.

“Marcus Rattigan bought Haney’s General Store? Why would he be interested in a little place like that?”

“Dunno,” said Frank. “But he snapped the place up when Haney sold out. The way things have grown up in north Stamford, the store is surrounded by houses now. It’s a nonconforming property in a two-acre zone. He can’t build on the lot or enlarge the building that’s there. I guess that’s why he was happy to let me have the lease.”

“He knows you’re planning to turn the place into a coffee bar?”

“Sure he knows. I certainly couldn’t do it without his approval. He and I are partners on the deal.”

“Partners. You and Marcus Rattigan?” It was all a little much to take in.

“Sure. Fifty-fifty. He supplied the building. I supply the know-how.”

Interesting. As far as I knew, my brother didn’t have any know-how.

“He even co-signed my loan at the bank.”

“He did?”

“Yup. Happy to do it, he said. Seeing as we were going to be partners and all.”

I stared at Frank suspiciously. “If you have a bank loan, what do you need me for?”

“As it happens, I’m running a little low on funds. You know how it is with construction. Estimates never seem to cover the final cost. In the beginning—”

“The beginning? How long ago did you get involved in this project?”

“It’s been about six weeks.”

“And I’m just hearing about it now?”

Frank shot me a look. As siblings went, we weren’t close. Though he only lived one town away, we’d never spent much time together. Our temperaments were just too dissimilar for us to really enjoy each other’s company. In fact, now that I thought about it, bad news was much more apt to bring us together than good.

“It seemed like the right time,” said Frank. “You know, with the opportunity for you and all. It’s not like I need the moon. I figure five thousand should do it.”

“Five thousand dollars?” I’d always suspected he was daft. Now I knew. There was no way I had that kind of money lying around, and if I did, I certainly wouldn’t have trusted Frank with it. “Where on earth would you think I’d get five thousand dollars?”

“All right, so you don’t ask Bob. You’ve been living in this house for what, eight, nine years? You must have some equity—”

“No.” I cut him off swiftly. “This is Davey’s and my home. I’m not going to risk losing it when you decide to go off and tilt at another windmill. You said Rattigan’s your partner. Why don’t you go to him?”

“I can’t. No way. Marcus put me in charge and I told him I could handle it. How would it look if the first time there was a problem I went running back to him?”

Not great. Even I had to admit that. “Look, Frank, I’m sorry. I just don’t have the kind of money you need.”

My brother took one last meaningful look around the room, but didn’t argue. Instead he pushed back his chair and stood. “Okay, I figured I’d ask. It was worth a shot.”

I picked up my jacket and pulled it on. “What will you do now?”

“I don’t know. I’ll have to think about it.” After a moment his expression brightened. “You’re not the only family I have, you know. Maybe I’ll talk to Aunt Peg.”

That would go over well, I thought, but didn’t voice the opinion aloud. As things turned out, I should have given him the money. It would have been easier than his next request.

Howard Academy was founded in 1928 by Joshua A. Howard, an enterprising gentleman of the early twentieth century who made a fortune in shipping, munitions and, it was rumored, bootlegging. Joshua, however, discovered rather too late in life that he might have been happier had he devoted half as much time to his wife and his children as he had to making money. Neither of his two sons had the brains to manage the empire he’d built; and his four daughters, all of whom had received the traditional education afforded to young females of the time, were vastly disinterested. Having accrued more money than he could ever hope to spend, and arriving at the unfortunate realization that his descendants could not be counted on to manage the fortune wisely, Joshua turned to philanthropy.

Aided by his spinster sister, Honoria Howard, he had founded Howard Academy, whose lofty aim was “to form the ideals and educate the minds of the young ladies and gentlemen who will shape America’s future.” Joshua chose as his setting what was then twenty acres of prime farmland, and was now a multimillion dollar enclave just north of downtown Greenwich. Howard Academy had taught the sons and daughters of senators, ambassadors, titans of industry, and at least two presidential candidates. Its alumnae and alumni had marched forth bravely into a world of power and privilege that was waiting to receive them.

With the passage of time, however, Howard Academy, which had once blithely assumed it would have its pick of Fairfield County’s best and brightest students, began to feel the heat of competition. The academy was now one of several private schools in Greenwich, all offering a superior education and all vying for the same children and the same limited endowment dollars. Not only that, but the administration had slowly come to realize that the rarefied atmosphere of white, upper class entitlement they’d prided themselves on was neither as desirable nor as politically correct as it once had been. Accordingly, some changes were in order.

Seeking a more culturally and economically diverse student body, Howard Academy hadn’t needed to look far to find a pool of qualified candidates. What they had needed to do for the first time in the school’s history, was hold a scholarship drive. As the twentieth century drew to a close, minority enrollment at Howard was nearly twenty percent. Student aid was also at an all-time high.

The school’s administration would have denied it, of course, but with an eye firmly fixed on the bottom line, Howard Academy now found itself with a strong incentive to admit students who might not reach the school’s high academic standards but whose parents were capable of paying full tuition. And if those parents were the generous sort, the kind likely to have checkbooks open and pens at the ready when the annual fund raising drive came around, it was said that admission could be virtually guaranteed.

Course material too rigorous for Junior? Curriculum too varied? That’s where I came in.

For the last half dozen years, I’d been happily employed as a special education teacher for the Stamford public school system. I liked the job and I loved the kids. Still, it was hard to be a working mother and a single parent. I needed more time to spend with my son, and more money wouldn’t have been all bad, either.

When I’d heard over the summer that Howard Academy was interviewing for the position of on-campus tutor, I spruced up my resume and sent it in. The idea was a lark, and nothing more. Aware of the school’s hallowed reputation and penchant for maintaining its ideals, I hadn’t thought I’d stand a chance. And then, with nothing to lose, I’d walked in and aced the interview.

Now, as of early September when the fall semester began, I was Howard Academy’s newest teacher. Ms. Travis. My first minor skirmish with the authorities had taken place over that quasi-feminist form of address. Apparently, I was the first woman teacher in the history of the school who wasn’t comfortable being pigeonholed as either a traditional Miss or Mrs.

I’d had to point out that miss was hardly appropriate since I was the mother of a six-year-old son, and what sort of example would that set for Howard Academy’s impressionable youth? As for Mrs., that was out, too. I wasn’t married and had no intention of maintaining a charade that implied otherwise.

Russell Hanover II, the school’s headmaster, had given in gracefully once I’d explained my position. Flexibility didn’t seem to be a strong suit of his, but as leader of one of Greenwich’s toniest private schools, he had beautiful manners. No doubt his mother had taught him at an early age that ladies were to be humored when it came to their preferred mode of address. How else to explain that the office staff, none of whom was younger than fifty, was collectively referred to as “the girls”?

Fortunately, at almost nine o’clock on a weekday morning, the traffic was moving briskly on North Street when I got off the Merritt Parkway and headed south toward downtown Greenwich. My new Volvo station wagon, a gift from ex-husband Bob to make up for four years of missing child support payments, clung to the bumps and curves in the road like a burr in a Collie’s tail.

Usually I like to go slowly and enjoy the view. With its landscaped lawns, imposing manor houses, and two-hundred-year-old stone walls, Greenwich is beautiful in any season of the year, and especially so in the fall when the weather is crisp and the leaves are shot through with vivid streaks of color. Today, there wasn’t time to look at anything but the clock.

Like many of the homes in the area, Howard Academy is set back from the road. The driveway is flanked by a pair of stone pillars. A small, discreet sign, gold lettering on a hunter-green background, announces that you’ve reached your destination.

The school itself sits on a wooded hilltop, one of the highest sites around. On a clear day it’s possible to see the Long Island Sound if you know just where to look. And if not, as any visitor quickly finds out, Russell Hanover will be delighted to show you.

Honoria Howard had envisioned her students doing their lessons in a milieu that was much like home, and on first approach,. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...