- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

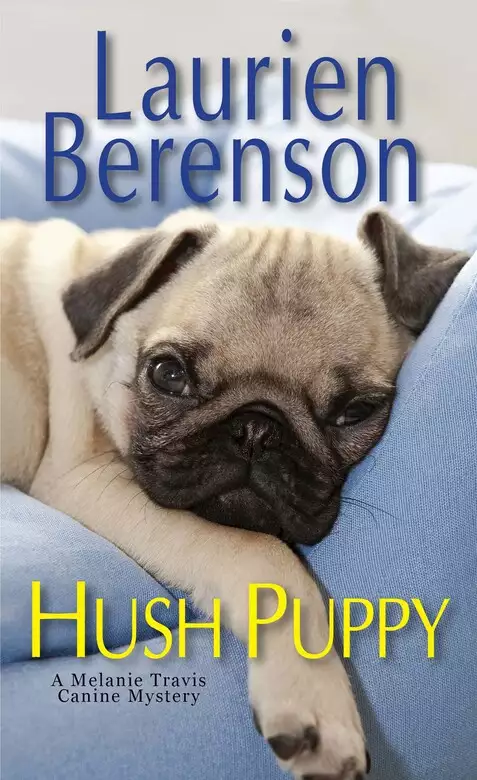

There’s a corpse on campus in this mystery from an Agatha Award finalist who’s “a rare breed of writer” ( The Plain Dealer). Melanie Travis loves her teaching job at Connecticut’s elite Howard Academy, where plans are underway for a Spring Pageant to honor the school’s fiftieth anniversary. Immersed in the preparations, Melanie is hurrying to retrieve a painting of one of the illustrious co-founders when she comes upon a disturbing scene: Eugene Krebbs, the Academy’s elderly caretaker, is arguing loudly with a girl half his size. Before Melanie can learn more than the girl’s first name—Jane—she disappears. It’s clear that Jane isn’t a student at Howard Academy, so what is she doing there? Melanie doesn’t have a chance to answer that question before more problems arise. Two days later, Krebbs is discovered stabbed to death right on the school grounds. Now Melanie is embroiled in a full-fledged homicide investigation as she tries to find out who’s added murder to the school's curriculum. “Fans of Miranda James’ Cat in the Stacks series may also enjoy Berenson.”— Booklist “If you like dogs, you’ll love Laurien Berenson’s Melanie Travis mysteries!”—Joanne Fluke, New York Times -bestselling author of the Hannah Swensen series

Release date: February 13, 2013

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 252

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Hush Puppy

Laurien Berenson

Sound advice, perhaps, but a rule I had trouble adhering to. As an adult, I’d come to realize she’d been speaking metaphorically, attempting to temper my natural enthusiasm with a bit of useful caution. No matter; by then the habit of throwing open doors and rushing gleefully onward was already deeply ingrained.

Being an optimist, I was always certain that whatever lay beyond each new portal would be a happy surprise, and the few bumps and scrapes I’d suffered along the way had done nothing to diminish that belief. Nevertheless, on that soggy March afternoon, as I hurried through the Howard Academy auditorium, climbed the half flight of steps, and went backstage to the prop room, I wasn’t expecting any surprises at all. Much less the one I found.

I’d been sent to find an oil painting of Honoria Howard, sister of early-twentieth-century robber baron, Joshua Howard, and cofounder of the school. Commissioned portraits of the pair hung side by side in the front hall of the stone mansion that formed the nucleus of the private academy. This painting, said to be of lesser quality, apparently also suffered the secondary sin of being monstrously unflattering. It had been relegated to storage and eventually found its way to the prop room, where it was hauled out on occasion when a set required period atmosphere.

Having seen the portrait Honoria favored, indeed having passed by it daily since taking the job as special needs tutor at Howard Academy the previous September, I was privately of the opinion that the woman had been lucky to find an artist who’d been able to record her countenance for posterity without flinching. If that painting featured her good side, I could readily understand why no one had wanted to find wall space for this one.

If I hadn’t been in such a hurry, the sound of voices, arguing loudly, might have given me pause. As it was, I’d already opened the door before I realized I might be intruding.

Eugene Krebbs, the school’s elderly caretaker, stood in the middle of the small, cluttered room. Wearing his customary overalls and hangdog expression, he was holding a broom in one hand and gesturing forcefully with the other.

He wasn’t a big man, and his clothes hung on him as if chosen to suit a larger frame. I judged him to be in his late sixties, though older wouldn’t have surprised me. His soft, fleshy features and watery brown eyes gave him a look of amiability that was at odds with a perpetually grumpy disposition.

Before coming to Howard Academy, I’d worked in the Connecticut public-school system for half a dozen years. There, the rules had been stringent, the budget adhered to, the paperwork endless. And a man like Krebbs would have long since been retired. Here he was only one of many private-school eccentricities I’d encountered in the last semester and a half.

His custodial skills were totally outdated—the broom he brandished was evidence of that—and a support staff seemed to do much of the actual work. I’d been told Krebbs had been a fixture at the school for decades. Everyone seemed to take his presence for granted, and though he never seemed to accomplish much, he was often to be found hovering glumly in the background.

I’d never had occasion to speak with Krebbs before; in fact, I wasn’t sure I’d ever heard him do more than mutter or mumble. Certainly I’d never heard him yell.

“You don’t belong here.” Krebbs shook the broom to reinforce his message. “Now take your butt and get out before I decide to turn you in.”

The object of his wrath was a girl. Standing beside an old couch, tangled in a jumble of moth-eaten velvet curtains, she looked barely half his size. The expression on her face was all angry defiance.

“You just try it!” she said with a sneer.

A student? I wondered, trying to place her. She looked about ten, which meant fifth grade. In my position as tutor, I taught a cross section of pupils from throughout the school, but this girl didn’t look familiar. She had short dark hair, a skinny build, and, I noted absently, remarkably dirty hands. Rather than wearing the school uniform, she was dressed in jeans and a sweatshirt. I was quite sure I’d never seen her before.

“Excuse me,” I said loudly. “Is there a problem here?”

Krebbs turned and glared. The girl moved swiftly. Slithering past him, she bolted for the door.

I blocked her path and held out my arms to catch her. Even though I was braced, she nearly knocked me down. Close up, she was tiny. Her chin barely came to the middle of my chest, and when my hand circled her arm, I felt only the bulky material of her sweatshirt, not the bone and sinew underneath.

“Not so fast,” I said. “Who are you? What’s your name?”

“What’s it to you?”

“See?” said Krebbs. “Like I said, she don’t belong here. She don’t even have a name.”

Surprisingly, his words seemed to wound the girl; or maybe it was the derision in his tone. “I do too have a name.”

“What is it?” I asked, looking back and forth between them. I wondered what she was doing in this musty, out-of-the-way room. And what she could possibly have done to make Krebbs so angry.

“Jane,” the girl said softly.

“Jane Doe, I’ll bet,” spat Krebbs.

I ignored him and said, “I’m Ms. Travis. Are you a student here?”

Jane tossed her head, the gesture looking oddly out of place on the small, elfin girl. “Not exactly.”

“She means no,” said Krebbs. “Look at her. Her clothes are dirty. She’s dirty—”

“Do you mind?” I snapped. There was no way Jane was going to talk to me in the face of the caretaker’s open hostility. He closed his mouth and stared at me sullenly.

It was too late. With a quick wrench, Jane pulled her arm free and raced out the door. Already several steps behind, I followed her across the stage and watched helplessly as she bounded down the steps, pushed open a side door, and was gone.

Frowning, I turned back. Krebbs had ambled out onto the stage and was sweeping listlessly, his broom seeming to disperse as much dust as it gathered.

“What was that all about?”

I had to ask the question twice. The first time, either Krebbs didn’t hear me or else he chose to ignore it. The second, I walked around in front of him and planted myself in his path.

“Eh?” he said.

“Who was that girl and why were you yelling at her?”

“I weren’t yelling. I thought about hitting her with the broom, though.” Krebbs smiled slightly, as though he found the notion satisfying.

“Why?”

“Trying to get rid of her. I been trying for a week, maybe more.”

“Where does she come from?”

“Heck if I know. She just showed up one day. Found her in the dining hall, snatching cookies out of the cupboard. She’s a thief, pure and simple. I ran her off, and I thought that was the end of it. But she came back, all right. Probably casing the place, with some kind of robbery in mind.”

The thought of that tiny slip of a girl masterminding a robbery was ludicrous. Krebbs seemed perfectly serious, though.

“Have you spoken to Mr. Hanover about her?”

Russell Hanover II was Howard Academy’s headmaster. Popular with parents and alumni alike, he was conservative, dedicated to the education of young minds, and starched stiffer than a nun’s habit. I couldn’t imagine he’d condone the caretaker’s heavy-handed tactics.

“Why would I do a thing like that?” asked Krebbs. “It’s my job to take care of the school, and that’s what I was doing. I would have gotten rid of her for good this time if you hadn’t of come along.

“You’re new around here.” His rheumy glare made the words sound like an accusation. “Maybe you don’t know how things work yet.”

“I know that you don’t go around chasing young girls with a broom. Nor trying to scare them half to death either.” I could see why Jane had felt the need to yell at this man. I was half-tempted myself.

“Things are different here than they are in public school,” Krebbs said with a snort. “People are different. You’d be a far sight better off if you took the time to figure that out before poking your nose into where it don’t belong.”

I pulled myself up, and said with dignity, “I am a teacher here, Mr. Krebbs. And as such, I am entitled to seek answers when I see a situation that strikes me as unusual. Why were you in the prop room?”

He shrugged and ducked his head. I was reminded of a dog indicating submission to a dominant male. In Krebbs’s case, however, I suspected the obeisance was all for show.

“Just doing my job. I came up onstage to sweep up and noticed that the door was open. Shouldn’t have been anyone in there this time of day, so I went and had a look.”

“What was Jane doing in there?”

Krebbs mumbled something under his breath.

“Pardon me?”

“Looked like maybe she was sleeping. She had some of them velvet curtains down and was using them for a blanket.”

Sleeping? Curiouser and curiouser. “And there was something about her demeanor that made you suspect she was dreaming of robbing the school?”

Maybe I shouldn’t have been so sarcastic. Certainly, Krebbs’s baleful look indicated as much. He picked up his broom and shuffled away across the stage.

I headed in the other direction and returned to the prop room. I hadn’t taken the time to look around before; now I did. The place was a mess. Old furniture, knickknacks, bits of costume and scenery were all piled haphazardly in the cramped space.

Howard Academy had hired a new drama coach at the end of January. Until then, the position had been handled in a perfunctory manner by the music teacher, who also ran the glee club. It was easy to see that her abilities had been overtaxed by both jobs. The prop room looked like it hadn’t been cleaned or organized in years. It was probably possible to trace the history of shows performed by moving each successive layer of junk to see what lay beneath.

A thick coating of dust covered fabric and upholstery alike, and the heavy burgundy curtains Jane had been using as a blanket were beginning to mildew as well. I lifted the drapes off the couch and shook them out. There was a small thump as something square and solid landed on my foot. A book had been nestled between the folds of material.

Setting the curtains aside, I reached down to see what Jane had been reading. The paperback had a bright, cheery cover: Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing. A stamp on the flyleaf proclaimed the book to be “Property of Howard Academy Library.” Judging by the crease in the spine, Jane had been about halfway through the play.

I wondered if she’d been enjoying it. Shakespeare was one of my favorites, but I’d been considerably older than ten when I’d started reading him. Even now, I was tutoring eighth graders who wouldn’t have dreamed of approaching the bard’s work without the comfort of a Cliffs Notes edition close at hand.

I folded the curtains and set them aside. The book I left on the couch where I’d found it. What little I knew about the elusive Jane had intrigued me. I hoped Krebbs hadn’t succeeded in scaring her off; I was looking forward to the opportunity of getting to know her better.

Thank goodness the prop room was small or I might have been there all afternoon. As it was, it took me twenty minutes to find Honoria’s portrait and another ten to pry it out from behind the cupboard where it had been wedged. The oil painting was of medium size, and encased in a massive gilt frame whose faded gold color did nothing to lighten the portrait’s somber tone.

For some reason, the artist had painted primarily in shades of brown and gray. Perhaps he’d decided that livelier colors didn’t suit his subject, for he’d portrayed Honoria, seated in a straight-backed chair, as a woman with rigid posture and stern, unbending features. Her eyes were small and deep-set and seemed to stare directly at the viewer. Her mouth was fixed in a line of permanent disgruntlement.

One of Honoria’s hands lay fisted in her lap. The other dangled at her side, its fingers twined through the topknot of a medium-sized gray dog. A Poodle, I realized, moving the portrait out into the light and taking a closer look, either a large Miniature or a small Standard. When I wiped away a decade’s worth of accumulated grime, the dog’s lion clip was clearly visible, identifying it as a relative, albeit distant, of Faith, my own Standard Poodle at home.

A small brass plaque screwed to the bottom of the frame read, “Honoria Howard and Poupee. 1936.” Honoria’s inclusion of the dog’s name along with her own made me smile. I knew very little about the school’s cofounder, but already I liked her better than I had a few minutes ago.

“There you are!”

I jumped slightly. The painting, propped on the floor but still heavy, swayed in my grasp. Michael Durant, the new drama coach, hurried to grab the other side of the frame. He was tall and slender, his build almost storklike, but there must have been strength in his arms because he held the portrait upright easily. He brushed back the dark brown hair that was long enough to curl around his collar and studied the painting with his usual intense gaze.

“I see you found the old witch. My God, she’s a handful, isn’t she? No wonder you didn’t bring the painting back. We were all wondering where you’d gotten to.”

By “all” he meant the rest of our newly formed Spring Pageant Committee. Six weeks earlier, Russell Hanover had come up with the idea of putting together a lavish drama production to celebrate the lives of Howard Academy’s founding family. In honor of this first-time endeavor, Michael had been added to the staff, and plans were now supposed to be taking shape.

The only problem was that although Russell’s idea seemed good in theory, nobody could quite figure out what the play was supposed to be about. By all accounts, Joshua Howard had been a shipping magnate whose methods had stopped just short of larceny. He was also rumored to have dabbled in bootlegging. And while I thought such topics would make for a lively and entertaining production, I could also understand why Russell felt the need to highlight other aspects of our esteemed founder’s life. If only someone could come up with any.

The week before, our somewhat desperate headmaster had formed an ad hoc committee, and, to my chagrin, I’d found my name at the bottom of the list. Our first meeting had taken place the previous Friday. In a frenzy of creativity befitting a bevy of educators, we’d brainstormed wildly. Everyone had thrown out ideas, and nothing had been settled.

This week when we met again, we were still at square one. It had been Sally Minor’s idea to dig up Honoria’s portrait and hang it in the teachers’ lounge where we were meeting in the hope that it might prove to be an inspiration. Sally had been at Howard Academy for more than a decade and was a prime source for all sorts of interesting snippets of past history.

“It’s just a ratty old painting,” she said. “I’m sure nobody’d care if we borrowed it and stuck it up in here.”

“Except maybe the other teachers who’d have to look at it all day.” Ed Weinstein smirked. He taught upper-school English and always seemed to be laughing at some private joke that he declined to share with the rest of us.

“I don’t think anyone would mind.” Rita Kinney was shy and soft-spoken, possessing a quiet beauty that she did nothing to enhance. She taught fourth through sixth grade history, and this was the first time she’d volunteered a thought. “I vote for giving it a try. It can’t hurt.”

Being the newest staff member in the group besides Michael, our leader, I’d been dispatched to hunt down the painting. “There was a bit of a problem,” I said.

“I guess there would be. I’ve never seen so much junk.” Michael lifted the painting free and laid it back against the couch. “This place is a pit, isn’t it? Your basic testament to the excesses of private education. Do you suppose they ever threw anything out? Or even thought of using it twice?”

He picked up the burgundy-velvet curtains I’d folded and tossed the heavy bundle on top of a similar pair in a faded shade of hunter green. A cloud of dust rose, then settled, around them. “Russell promised me free rein with the drama department, such as it is. I can see the first order of business better be cleaning this room.”

“After we come up with a theme for the pageant,” I said firmly. “Did the committee think of anything after I left?”

“Lots of things, none of them useful. We did manage to pass a rule prohibiting smoking at the meetings.”

“Ed?” I ventured.

“Ed. He seemed to think that if he stood next to the window when he lit up, nobody would mind. Sally changed his mind about that pretty quickly.”

“She would.” I grinned. “Do you really think we ought to take this monstrosity back and hang it up?”

“The committee voted for it.” Michael squatted down in front of the painting. “I’m happy to bow to majority rule. Who’s the artist anyway? Is there a signature?”

“Just initials.” I’d already looked. “R.W.H., whoever that is.”

“Maybe an artist with too much taste to want his name associated with the finished product? Hey, what’s this?” Michael read the plaque on the bottom of the frame, then looked at the dog in the lower corner of the picture. “Poupee? Silly name for a rather silly looking dog.”

“It’s a Poodle,” I told him. “Probably a small Standard. Even though they were originally bred in Germany, lots of people still think of them as French Poodles. I would imagine that’s how he got the name. As to the silly looking trim, that’s not his fault. In those days, it was called a lion trim. Now we use a variation called a continental in the show ring.”

Michael stood up and dusted off his hands. “How do you know so much about it?”

“I have a Poodle at home that looks quite a bit like that one. My aunt breeds Standard Poodles. She’s shown them for years, and now she’s got me doing it, too.”

“I have to admit it’s a pretty distinctive look, with the hair long on the front and all shaved off in back. Maybe we could use your dog in the pageant.”

“Doing what?” I asked, surprised.

“She could play the part of Poupee.” Michael saw the expression on my face and grinned. “Hey, don’t knock it. That’s probably the best idea we’ve come up with all week.”

Somehow, that wasn’t a comforting thought.

By the time we got back to the teachers’ lounge, the rest of the committee had grown tired of waiting for us and gone home. Meetings held at the end of the day on Friday are never popular, especially as Howard Academy has early dismissal so that everyone can get a jump on their weekend plans. Some of my students would be heading north with their parents to ski; others, south, in search of sun. At least one had theater tickets for Broadway and another was planning to go fox hunting.

As for me, I was heading home to let out the dog and meet my six-year-old son, Davey’s, school bus. We’d have milk and cookies together, and he’d tell me about his day. After that, I had to give Faith a bath as she was entered in a dog show that weekend where I had high hopes of picking up some much-needed points toward her championship. I wouldn’t have traded places with anyone.

As always, Faith was waiting by the door when I got home. She whined softly as I fitted the key to the lock, then launched herself into the air in a frenzy of greeting as the door swung open. Standards are the largest of the three varieties of Poodles. Faith stands twenty-four inches at the shoulder and weighs more than forty pounds. Catching her in full flight requires both strength and dexterity, but I was used to the task by now.

Margaret Turnbull, Faith’s breeder and my Aunt Peg, would have been horrified to see one of her dogs exhibit such a lack of manners. The Cedar Crest Standard Poodles are an illustrious line, well-known throughout the dog show world for producing generation after generation of eye-catching champions. Each of Aunt Peg’s dogs is impeccably trained, and she never allows anything less than the best behavior.

Unfortunately for me, it’s a standard she also applies to her relatives.

Since Aunt Peg wasn’t around to see, however, I gave Faith a hug and ruffled my hands through the long black mane coat on the front half of her body. Poodles have long been one of the most popular breeds in the world and, as an admittedly biased owner, it wasn’t hard for me to see why. Beneath the highly stylized show clip, Faith was a dog of uncommon intelligence and dignity. She understood my moods and most of what I said, and had a marvelous sense of humor. In short, she was the perfect companion.

It didn’t surprise me that Honoria Howard had chosen to include her Poodle when she’d had her portrait painted. Poodle owners tend to think of their pets as members of the f. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...