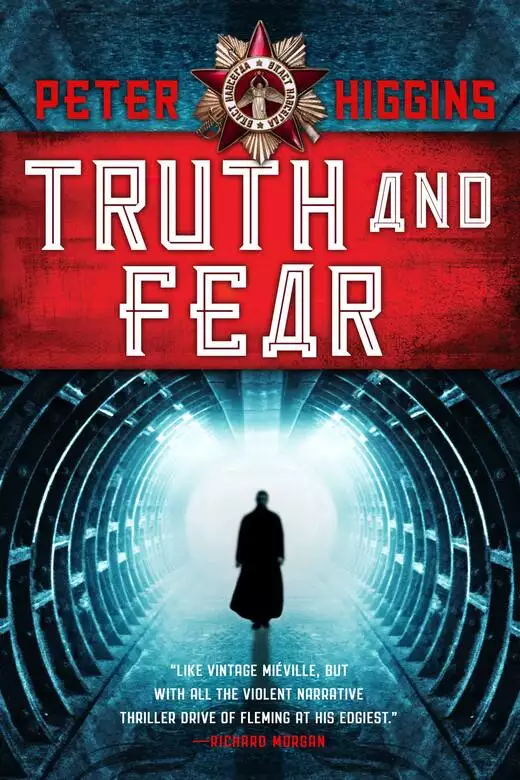

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Investigator Lom returns to Mirgorod and finds the city in the throes of a crisis. The war against the Archipelago is not going well. Enemy divisions are massing outside the city, air raids are a daily occurrence and the citizens are being conscripted into the desperate defense of the city.

Release date: March 25, 2014

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Truth and Fear

Peter Higgins

Low on the city’s eastern horizon, a gap opens in the growing milky bruise of morning and a surprising sliver of sun, a solar squint, spills watery light. The River Mir that has flowed black through the night kindles suddenly to a wide and wind-scuffed green. An exhalation of water vapour, too thin to be called a mist, rises off the surface. The breath of the river quickens and stirs, and on its island between the Mir and the Yekaterina Canal, moored against the embankment of the Square of the Piteous Angel, the Lodka condenses out of the subsiding night, blacker and blacker against the green-tinged yellowing sky. Its cliff-dark walls seem to belly outwards like the sides of a momentous swollen vessel. The jumbled geometry of its roofscape is forested with a hundred flagpoles, and from every pole a red flag edged with black hangs at half mast, draped and inert. Banners hang limply from parapets and window ledges: repetitious, identical fabrics of blood and black, the officious, unwavering, requiring stare of collective mourning.

Within the walls of the Lodka, the unending work of the Vlast goes on. Its skeleton crew, the three thousand watchkeepers of the night–civil servants, diplomats, secret police–are completing their reports and tidying their desks. First light is falling grey through the grimed glass dome onto the still-empty galleries of the Central Registry, where the great wheel of the Gaukh Engine stands motionless but expectant. On hundreds of yards of unlit shelving, the incoming files–the accusations and denunciations, the surveillance records, the intercepted communications–await the archivists of the new day. The stone slabs of the execution yards are being scrubbed and scoured with ammonia, and in the basement mortuary the new arrivals’ slabbed cadavers seep and chill.

In the Square of the Piteous Angel the morning light loses its first bright softness and grows complacent, ordinary and cold. Along the embankment the whale-oil tapers, burning in pearl globes in the mouths of cast-iron leaping fish, are bleached almost invisible, though their subtle reek still fumes the dampness of the air. The iron fish have heavy heads and bulging eyes and scales thick-edged like fifty-kopek coins. Their lamps are overdue for dousing. The gulls have risen from their night-roosts: they wheel low in silence and turn west for the shore.

And on the edge of the widening clarity of the square’s early emptiness, the observer of the coming day stands alone, in the form of a man, tall and narrow-shouldered in a dark woollen suit and grey astrakhan hat. His name is Antoninu Florian. He takes from his pocket a pair of wire-framed spectacles, polishes with the end of his silk burgundy scarf the circular pieces of glass that are not lenses, and puts them on.

It is more than two hundred years since Antoninu Florian first watched a morning open across Mirgorod. Half as old as the city, he sees it for what it is. Its foundations are shallow. Through the soles of his shoes on the cobbles he feels the slow seep and settle of ancient mud, the deep residuum of the city-crusted delta of old Mir: the estuarial mud on which the Lodka is beached.

The river’s breath touches Florian’s face, intimate and sharing. Cold moisture-nets gather around him: a sifting connectedness; gentle, subtle water-synapses alert with soft intelligence. Crowding presences move across the empty square and tall buildings not yet there cluster against the skyline. The translucence of a half-mile tower that is merely the plinth for the behemoth statue of a man. Antoninu Florian has seen these things before. He knows they are possible. He has returned to the city and found them waiting still.

But today is a different day. Florian tastes it on the breath of the river. It is the day he has come back for. The long equilibrium is shifting: flimsy tissue-layers are peeling away, the might-be making way for the true and the is. And in Florian’s hot belly there is a feeling of continuous inward empty falling, a slow stumble that never hits the floor: he recognises it as quiet, uneasy fear. The breath of the river brings him the scent of new things coming. It tugs at him. Urges him. Come, it says, come. Follow. The woman who matters is coming today.

Florian hesitates. What he fears is decision. Choices are approaching and he is unsure. He does not know what to do. Not yet.

The curiosity of a man’s gaze rakes the side of his face. A gendarme is watching him from the bridge on the other side of the square. Florian feels the involuntary needle-sharpening of teeth inside his mouth, the responsive ache of his jaw to lengthen, the muscles of neck and throat to bunch and bulk. His human form feels suddenly awkward, inadequate, a hobbling constraint. But he forces it back into place and turns, hands in pockets, narrow shoulders hunched against the cold he does not feel, walking away down Founder’s Prospect.

The gendarme does not follow.

In her office high in the Lodka, on the other side of the Square of the Piteous Angel, Commander Lavrentina Chazia, chief of the Mirgorod Secret Police, put down her pen and closed the file.

‘We are living in great days, Teslom,’ she said. ‘Critical times. History is taking shape. The future is being made, here and now, in Mirgorod. Do you feel this? Do you taste it in the air, as I do?’

The man across the desk from her said nothing. His head was slumped forward, his chin on his chest. He was breathing in shallow ragged breaths. His wrists were bound to the arms of his chair with leather straps. His legs, broken at the knees, were tied by the ankles. His dark blue suit jacket was unbuttoned, his soft white shirt open at the neck: blood had flowed from his nose, soaking the front of it. He was a small, neat man with rimless circular glasses and a flop of rich brown hair, glossy when he was taken, but matted now with sweat and drying blood. Not a physical man. Unused to enduring pain. Unused to endurance of any kind.

‘Of course you feel it too,’ Chazia continued. ‘You’re a learned fellow. You read. You watch. You study. You understand. The Novozhd is dead. Our beloved leader cruelly blown apart by an anarchist’s bomb. I was there, Teslom. I saw it. It was a terrible shock. We are all stricken with grief.’

The man in the chair groaned quietly. He raised his head to look at her. His eyes behind their lenses were wide and glassy.

‘I’ve told you,’ he said. ‘A hundred times… a thousand… I know nothing of this. Nothing. I… I am… a librarian. An archivist. I keep books. I am the curator of Lezarye. Only that. Nothing more.’

‘Of course. Of course. But the fact remains. The Novozhd is dead. So now there is a question.’

The man did not reply. He was staring desperately at the heavy black telephone on the desk, as if its sudden bell could ring salvation for him. Let him stare. Commander Chazia stood up and crossed to the window. Mirgorod spread away below her towards the horizon under the grey morning sky. The recent floods were subsiding, barges moving again on the river.

There had been rumours that when the recent storms were at their height sentient beasts made of rain had been seen in the city streets. Dogs and wolves of rain. Rain bears, walking. Militia patrols had been attacked. Gendarmes ripped to a bloody mess, their throats torn out by hard teeth of rain. And rusalkas had risen from the flooded canals and rivers. Lipless mouths, broad muscular backs and chalk-white flesh. With expressionless faces they reached up and pulled men down to drown in the muddied waters. The rumours were probably true. Chazia had made sure that the witnesses and the story-spreaders were quietly shot in the basement cells of the Lodka. It was good that people were afraid, so long as they feared her more.

She had left Teslom long enough. She turned from the window and walked round behind his chair. Rested her hand on his shoulder. Felt his muscles quiver at her gentle touch.

‘Who will rule, Teslom? Who will have power? Who will govern now that the Novozhd is dead? That’s the question here. And you can help me with that.’

‘Please…’ said Teslom. His voice was almost too quiet to hear. ‘Please—’

‘I just need your help, darling. Just a little. Then you can rest.’

‘I…’ He raised his head and tried to turn towards her. ‘I… I can’t…’

Chazia leaned closer to hear him.

‘Let’s go over it again. Tell me,’ she said. ‘Tell me about the Pollandore.’

‘The Pollandore…? A story. Only a story. Not a real thing… not something that exists… I’ve told you—’

‘This is a feeble game, Teslom. I’m not looking for it. It isn’t lost. It’s here. It’s in this building. I have it.’

He jerked his head round. Stared at her.

‘Do you want to see it?’ said Chazia. ‘It would interest you. OK, let’s do that, shall we? Maybe later. When we can be friends again. But first—’

‘If you already have it, then…’

‘The future is coming, Teslom. But who will shape it? Tell me about the Pollandore.’

‘I will tell you nothing. You… you and all your… you… you can all fuck off.’

Chazia unbuttoned her uniform tunic, took it off and hung it on the back of Teslom’s chair. He was staring at the telephone again.

‘Do you know me, Teslom?’ she said gently.

‘What?’

‘I think you do not. Not yet.’

She rolled the sleeves of her shirt above the elbow. The smooth dark stone-like patches on her hands were growing larger. Spreading up her arms. The skin at the edges was puckered, red and sore and angry. The itching was with her always.

‘Let’s come at this from a different direction,’ she said. ‘A visitor came to the House on the Purfas. An emissary from the eastern forest. A thing that was not human. An organic artefact of communication. You’re surprised that I know this? You shouldn’t be. Your staff were regular and thorough in their reports. But I’m curious. Tell me about this visitor.’

She was stroking him now. Standing behind him, she smoothed his matted brown hair. He jerked his head away.

‘No,’ he said hoarsely. ‘I choose death. I choose to die.’

‘That’s nothing, Teslom.’ She bent her head down close to his. She could smell the sourness of his fear. ‘Everyone dies,’ she breathed in his ear. ‘Just not you. Not yet.’

As she spoke she slid her stone-stained hand across his shoulder and down the side of his neck inside his bloodied shirt, feeling his smooth skin, his sternum, the start of his ribs. She felt the beating of his heart and rested her hand there. Closing her eyes and feeling with her mind for the place. She had done this before, but it was not easy. It needed concentration. She let her fingers rest a moment on the gap in his ribs over his heart. Teslom was still. Scarcely breathing. He could not have moved if he wanted to: with her other hand she was pressing against his back, using the angel-flesh in her fingers to probe his spinal cord, immobilising him.

She had found the place above his heart. She dug the tips of her fingers into the rib-gap, opening a way. It needed technique more than strength, the angel-substance in her hand did the work. Teslom’s quiet moan of horror was distracting, but she did it right. She reached inside and cupped his beating heart in her palm. And squeezed.

His eyes widened in panic. He could see her hand deep in his chest. He could see there was no blood. No wound. It was not possible. But it was in there.

‘Are you listening to me, Teslom?’

He was weak. Cold sweat on the dull white skin of his face, livid blotches over his cheekbones. Chazia released the pressure a little. Let his heart beat again.

‘Are you listening to me?’

He shifted his head almost imperceptibly to the left. An attempt at a nod.

‘Good. So. This strange living artefact, this marvellous emissary from the forest. Why did it come? What did it want? Did it concern the Pollandore?’

‘It… I can’t…’

Chazia adjusted her grip on his heart.

‘There,’ she said. ‘Is that better? Can you talk now?’

‘Yes. Yes. Oh please. Get it out. Get it out. Stop.’

‘So tell me.’

‘What?’

‘The messenger. From the forest.’

‘It… addressed the Inner Committee.’

‘And what did it say?’

‘It said… it said there was an angel.’

‘An angel?’

‘A living angel. It had fallen in the forest and it was trapped there. It was foul and doing great damage. Oh. Please. Don’t…’

Chazia waited. Give him time. Let him speak. Patience. But his head had sunk down again and there was a congested bubbling in his chest. Perhaps she had been too harsh. Overestimated his strength. The silence lengthened. She lessened the pressure on his heart but kept her hand in place. It was the horror of seeing it in there, as much as anything, that made them speak.

‘Teslom?’ she said at last. ‘Tell me more. The forest is afraid of this living angel? Afraid it will do terrible things?’

‘Yes.’

‘And so? This emissary. Why did the forest send it? Was it the Pollandore?’

‘Of course. Yes. Open the Pollandore, it said. Now. Now is the time. Before it’s too late.’

‘Too late? For what?’

‘The Pollandore is breaking. It is failing, or leaking, or waking, or… something. I don’t know. I didn’t understand. It wasn’t clear… I can’t… I need to stop now… rest… please… for fuck’s sake…’

He coughed sour-smelling fluid out of his mouth. Viscous spittle stained with flecks of red and pink. It spilled on her forearm. It was warm.

‘You’re doing fine, Teslom. Good. Very good. Soon it will be over. Just a few more questions. Then you can rest.’

He struggled for breath, trying to bring his hands up to push her off. But his hands were strapped to the chair.

Chazia sensed his strength giving out. He was on the edge of death. She tried to hold him there, but she didn’t have complete control. There was a margin of uncertainty. But they had come to the crisis. The brink of gold. Crouching down beside him, she rested her head on his shoulder, her cheek against his.

‘Just tell me, darling,’ she said quietly. ‘How was the Pollandore to be opened?’

‘There was a key.’ He was barely whispering. ‘The paluba–the messenger–it brought a key.’

‘What kind of key?’

‘I don’t know. I didn’t see it. I wasn’t there. I heard. Only heard. Not a key. Not exactly. Not like an iron thing for a lock. But a thing that opens. A recognition thing. An identifier. I don’t know. The paluba offered it to the Inner Committee. Oh shit. Stop. Please.’

‘And what did the Inner Committee do?’

‘Nothing.’

‘Nothing?’

‘They refused the message. They were afraid. What could they do? They didn’t have the Pollandore. They lost it. The useless fuckers lost it long ago. Please—’

‘So?’

‘So they sent it away. The paluba. They sent it away.’

‘What happened then? What did the paluba do? Where did it go? What happened to the key?’

He closed his eyes. His head sank forward again. She was losing him.

‘Your daughter, Teslom. You have a daughter. You should think of her.’

‘What?’

‘She is pregnant.’

‘No… not her… Leave her alone!’

‘If you fail me now, I will reach inside your daughter’s belly for her feeble little unborn child–it’s a girl, Teslom, a girl, she doesn’t know this but I do–and I will take its skull between my fingers… like this…’ She paused. ‘Are you listening to me?’

‘Yes.’

‘Do you know that I will do this? Do you know that I will?’

She squeezed his heart again, gently. He screamed.

‘It’s all right, darling,’ she whispered in his ear. ‘Nearly finished now. Think of your daughter, Teslom. Think of her child.’

‘Oh no,’ he gasped. ‘Oh no. No.’

‘Where is the key to the Pollandore? Tell me how to find it.’

‘I don’t know!’

‘Then who? Who knows?’

‘The woman,’ said Teslom, so quiet Chazia could hardly hear. ‘The woman,’ he said again. ‘Shaumian.’

‘What? Say it again, darling. Say the name again.’

‘Shaumian. The key. It would go to the Shaumian woman next. If not the Committee… then Shaumian. Shaumian!’

Chazia felt her own heart beat with excitement. Shaumian. She knew the name. And it led to another question. The most important question of all.

‘Teslom?’

‘No more. Please. I can’t—’

‘Just one more thing, sweetness, and then you can have some peace. There are two Shaumian women. Was it the mother? Or the daughter? Which one was it, darling? Which one?’

‘I don’t know. It doesn’t matter. Either. What’s the difference? It makes no difference. It doesn’t—’

‘Yes, it matters. The mother is dead. The mother dead, the daughter not. That’s the difference, darling. Mother or daughter?’

Teslom choked and struggled for breath. He was mouthing silence like a fish drowning in air. Chazia waited. Everything depended on what he said next.

‘Mother or daughter?’ whispered Chazia gently. ‘Mother or daughter, darling?’

‘Daughter then.’ His voice was almost too quiet to hear. ‘Daughter. The key would be for the daughter.’

‘Maroussia Shaumian? Be sure now. Tell me again.’

‘Yes! For fuck’s sake. I’m telling you. That’s the name. Shaumian. Shaumian! Maroussia Shaumian!’

He was screaming. Chazia felt his heart clenching and twitching in her hand. Shoving the blood hard round his body. He was working his lungs fast and deep. Too fast. Too deep.

It didn’t matter. Not any more. She squeezed.

When she had killed him, she withdrew her hand from his chest, wiped it carefully on a clean part of his shirt and went back round to her side of the desk. Turned the knob on the intercom box. Pulled the microphone towards her mouth.

‘Iliodor?’

‘Yes, Commander.’ The voice crackled in the small speaker.

‘There is a mess in my office. Have it cleared away. And I need you to find someone for me. A woman. Shaumian. Maroussia Shaumian. There is a file. Find her for me now, Iliodor. Find her today and bring her to me.’

Vissarion Lom and Maroussia Shaumian took the first tram of the day into Mirgorod from Cold Amber Strand. Marinsky Line. Cars 1639, 1640 and 1641, liveried in brown and gold, a thick black letter M front and back on each one. Four steep clattering steps to climb inside. Slatted wooden benches. Standard class, single journey, no luggage: 5 kopeks. There were few other passengers: in summer holidaymakers came to Cold Amber Strand for the bathing huts, the pleasure gardens, the bandstand, the aquarium, but now winter was closing in. Signs above the seats warned them: CITIZEN, YOU ARE IN PUBLIC NOW! BEWARE OF BOMBS! WHOM ARE YOU WITH?

They went to the back of the car and Lom took a seat opposite Maroussia, facing forward to watch the door. He kept his hand in the pocket of his coat, holding the revolver loosely. A double-action Sepora .44 magnum. It was empty. But that was OK. That was better than nothing.

The tram hummed and rattled and accelerated slowly away from the stop. Maroussia huddled into the corner and stared out of the window, eyes wide and dark. Flimsy shoes. Bare legs, pale and cold.

‘The Pollandore is in Mirgorod,’ said Maroussia. ‘It must be. Vishnik knew where it was–he found it, and he was looking in the city. So it’s in the city. That’s where it is.’ She frowned and looked away. ‘Only I don’t know where.’

‘We’ll start at Vishnik’s apartment,’ said Lom. ‘He had papers. Photographs. Notes. We’ll go and look. After we’ve eaten. First we need to find some food. Breakfast.’

‘I left my bag at Vishnik’s,’ said Maroussia. ‘I’ve got clothes in it. Clothes and money and things. Maybe the bag’s still there.’

‘Maybe,’ said Lom.

‘I can’t go back to my room,’ said Maroussia.

‘No.’

‘They’ll be waiting. Watching. The militia…’

‘Possibly,’ said Lom. ‘Don’t worry. We’ll be fine—’

Lom broke off. A woman with two children got on the tram and took the seat behind Maroussia. Maroussia withdrew further into the corner and closed her eyes. She looked tired.

The city opened to take them back. A fine rain greyed the emptiness between buildings. It rested in the air, softening it, parting to let the tramcars pass and closing behind them. The streets of Mirgorod were recovering from the flood. River mud streaked the pavements and pools of water reflected the low grey sky. Businesses were closed and shuttered, or gaped, water-ransacked and abandoned. People picked their way across plank-and-trestle walkways between piles of ruined furniture stacked in the road. Sodden mattresses, rugs, couches, wardrobes, books. A barge, lifted almost completely out of the canal and left beached by the flood, jutted its prow out into the road. A giant in a rain-slicked leather jacket was shouldering it off the buckled railings and trying to slide it back into the water. Gendarmes and militia patrols stood on street corners, checking papers, watching the clearing-up. They seemed to be everywhere. More than usual.

Lom leaned forward and slid open a gap in the window, letting the cold city air pumice his face. He inhaled deeply: the taste of coalsmoke, benzine, misting rain and sea salt was in his mouth–the taste of Mirgorod.

Maroussia’s shoulder was raised protectively, half-turned against him. Her face was almost a stranger’s face, at rest and unfamiliar in sleep. She was almost a stranger to him. He knew almost nothing about her, nothing ordinary at all, but he knew the most important thing. She had set her will against the inevitability of the world. The Vlast had come for her, for no reason that she knew–not that the Vlast needed reasons–but Maroussia hadn’t gone slack, as so many did, numbed by the immensity and inertia of their fate. She had seized on the vague and broken hints of the messenger that came from nowhere–from the endless, uninterpretable forest–and she had turned them into the engine of her own private counter-attack against… against what? Against unchangeability, against the cruelty of things.

But the energy of her counter-attack was Maroussia’s own. It came from dark inward places. She was alone, unsanctioned, uninstructed. Lom couldn’t have said with certainty what she thought she was going to achieve, or how, and it seemed not really possible, in the cold grey light of the morning return to the city, that she could do anything at all: Mirgorod was the foremost city of the continental hegemony of the Vlast, four hundred years of consolidated history, and they were two alone, without a map of the future, without a plan. But what struck him was how irrelevant the impossibility of her purpose was. It was its asymmetric absurdity that gave it meaning and shape. The undercurrent of almost unnoticed fear that he was feeling now was fear for her. He had none for himself. He had never felt more alive. He was relaxed and open and strong. He would do what he could when whatever was coming came; he would stand with her side by side. Her mouth was slightly open in sleep, and she was doing the bravest, loneliest thing that Lom had ever seen done.

The healing wound in the front of his skull pulsed almost imperceptibly under fine new skin with the beating of his heart. He pulled off the white scrap of cloth he’d tied round his forehead. It was unnecessary and conspicuous. As he stuffed it into his pocket, he felt the touch of something else: a quiet stirring under his fingers. He brought the thing out and cupped it in his palm. A small linen bag stained with dried blood. He’d forgotten he had it. He opened it and took out the strange small knotted ball of twigs and wax, tiny bones and dried berries. Brought it up to his face and breathed its earthy, resinous air. A woodland taint. He slipped the small thing back into its bag. It was a survivor.

The tram got more crowded as they approached the city centre: squat, frowning women with empty string bags; workers going to work, each absorbed in their own silence. More than half the passengers were wearing black armbands. Lom wondered why. It was odd. Looking out of the window, he saw checkpoints at the major intersections. Traffic was backed up in the streets and people were lining up along the pavement to show their papers. The pale brick-coloured uniforms of the VKBD were out in force. Mirgorod, police city. Something was happening.

‘Pardon me please. May I?’

A man with thinning hair and a crumpled striped suit slid onto the seat next to Maroussia. He rested a cloth attaché case on his knees, opened it and took out a paper bag. Nodding apologetically at Lom, he started to eat a piece of sausage.

‘Sorry,’ the man said. ‘Running late. Crowds everywhere. I’ve had my cards looked at twice already. The funeral, I guess. Back to normal tomorrow.’

Lom gave him a What can you do? shrug and went back to watching through the window. The sausage smelled strongly of garlic and paprika.

Fifteen minutes later the tram pulled up at the terminus and the engine cut out. People started to stand up and shuffle down the aisle. The man sitting opposite Lom put his empty sausage bag into his attaché case and clicked it shut. He glanced out of the window and swore under his breath.

‘Not again,’ he said. ‘I’m going to be late. Damn, I don’t need this, not today.’ He got up with a sigh and joined the back of the line.

Lom stayed where he was and took a look out of the window to see what the problem was. There were four gendarmes on the platform. Two were stopping the passengers as they got off–looking at identity cards, comparing photographs to faces–while the other two stood back, watchful, hands on their holsters. One of the watchers was a corporal. The checkpoint was set up right. The men were awake and alert and doing it properly. The corporal knew his stuff.

Lom had to do something. He needed to think.

Maroussia stirred and woke. Her cheeks were flushed and her hair was damp. Stray curls stood out from the side of her head where it had pressed against the window. She looked around, confused.

‘Where are we?’ she said.

Lom began buttoning his cloak. Taking his time, but making it look natural. Not like he was avoiding joining the queue.

‘End of the line,’ he said quietly. ‘Marinsky-Voksal. But there’s trouble.’

Maroussia turned to see, and took in at a glance what was happening. She bent forward to adjust her shoe.

‘Are they looking for us?’ she whispered.

‘Not necessarily. But possibly. Can’t discount it. I’ve got no papers. Have you?’

‘No.’

‘OK,’ said Lom. ‘We’ll separate. I’ll go first. Give them something to think about. You slip away while I’ve got them occupied.’ Maroussia started to protest, but Lom had already stood up and joined the end of the resigned shuffling queue.

He was getting near the exit. There were only two or three passengers ahead of him, waiting with studied outward patience, documents ready in hand. One of the gendarmes was examining identity cards while the other peered over his shoulder into the tram, scrutinising the line. Lom saw his eyes slide across the faces, pass on, hesitate, and come to rest on Maroussia with a flicker of interest. He checked against a photograph in his hand and looked at her again, a longer, searching look. He took a step forward.

Shit, thought Lom. I can’t let us be taken. Not like this. That would be stupid. His fingers in his pocket closed on the grip of the empty Sepora .44.

He felt an elbow in his ribs.

‘Excuse me, please!’

It was Maroussia, pushing past him and heading for the gendarme.

‘Excuse me!’ she said again in a loud voice.

‘What are you doing?’ hissed Lom, putting his hand on her arm.

‘Making time,’ she said. ‘Not getting us killed.’

She pulled her arm free, pushed past the waiting passengers and spoke to the gendarme.

‘You must help me, please,’ she said firmly. ‘Take me to the nearest police station. At once. My name is Maroussia Shaumian. I am a citizen of this city. A militia officer murdered my mother. He also tried to kill me. I want protection and I want to make a statement. I want to make a complaint.’

The gendarme stared at her in surprise.

‘You what?’

‘You heard me,’ said Maroussia. ‘I want to make a complaint. What is your name? Tell me please.’

Lom stepped up beside her.

‘Stand aside, man,’ he said to the gendarme. Peremptory. Authoritative. ‘I’m in a hurry. This woman is in my custody.’

The gendarme took in his heavy loden coat, mud-stained at the bottom. The healing wound in his forehead.

‘And who the fuck are you?’ he said.

‘Political Police,’ said Lom.

‘You don’t look like police. Let’s see your ID.’

‘I am a senior investigator in the third department of the Political Police,’ said Lom. ‘On special attachment to the Minister’s Office.’

‘You got papers to prove that?’

‘Vlasik,’ said the corporal, ‘

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...