- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

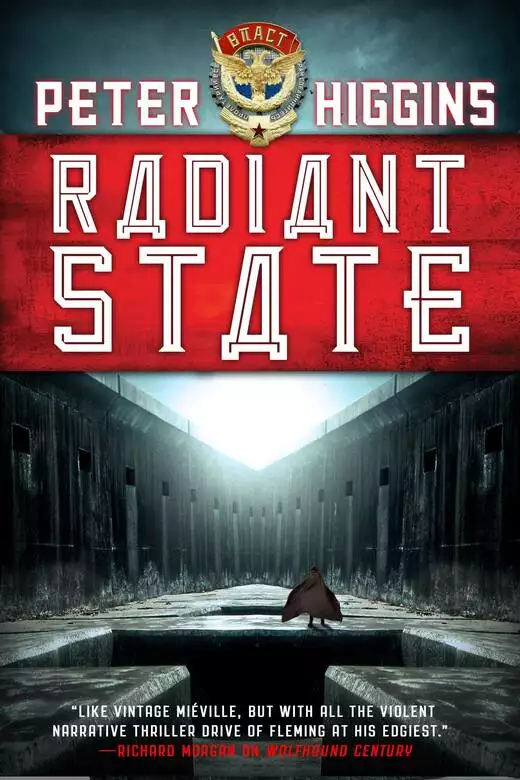

Peter Higgins's superb and original creation, a perfect melding of fantasy, myth, SF and political thriller, reaches its extraordinary conclusion. The Vlast stands two hundred feet tall, four thousand tons of steel ready to be flung upwards on the fire of atom bombs. Ready to take the dream of President-Commander of the New Vlast General, Osip Rizhin, beyond the bounds of this world. But not everyone shares this vision. Vissarion Lom and Maroussia Shaumian have not reached the end of their story, and in Mirgorod a woman in a shabby dress carefully unwraps a sniper rifle. And all the while the Pollandore dreams its own dreams.

Release date: May 19, 2015

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 308

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Radiant State

Peter Higgins

We will lay out the stars in rows and ride the moon like a horse.

Vladimir Kirillov (1889–1943)

On the canals of Mars we will build the palace of world freedom.

Mikhail Gerasimov (1889–1939)

She sees with eyes too wide, her ears are deafened with too much hearing, she feels with her skin. She is the first bold pioneer of a new generation: Engineer-Technician 2nd Class Mikkala Avril. Age twenty-three? Age zero! Fresh-born raw today, in the zero day of the unencompassable zero season of the world, she descends the gangway of the small plane sent personally for her, the only passenger, under conditions of supreme urgency. Priority Override. (The plane is still in its shabby olive livery of war: no time is wasted on primping and beautifying in the New Vlast of Papa Rizhin.) Reaching the foot of the wobbling steel stair, she steps out onto the tarmac of the Chaiganur cosmodrome, Semei-Pavlodar Province, and into the heat of the epochal threshold hour.

To be part of it. To do her task.

The almost-bursting heart in her ribs is the heart of her generation, the heart of the New Vlast, a clever strong young heart pounding at the farthest limit of endurability, equal parts dizzying excitement and appalling terrible fear.

Today will be a day like no other.

It is not yet quite six years since the armies of the enemy surrounding Mirgorod were swept from the face of the planet in a cleansing, burning wind by Rizhin’s new weapon, a barrage of atomic artillery shells. Not quite six years–the vertebrae of six long winters articulated by the connective tissue of five roaring summers–but for the New Vlast the time elapsed has delivered far more and felt far longer. General Osip Rizhin, President-Commander of the New Vlast and Hero of the Peace of a Thousand Years, has taken time by the scruff of the neck. He has stretched the weeks tight like wire and made each day work–work!–like days never worked before.

Some may express doubt that all this can been achieved so quickly, Rizhin said on First Peace Day, outlining his Five Year Plan, his Great Step into the Future. But the doubters have not grasped the true nature of time. Time is not a dimension, it is a means of production. Time is too important to be trusted to calendars and clocks. Time is at our disposal and will march at our speed, if we are determined. It is a matter of the imposition of human will.

Rizhin had seen the Goal and envisaged the completion of Task Number One. It would be delivered at the speed that he set.

And so it was. In two thousand hammer-blow days, each day a detonation like an atomic bomb, he made the whole planet beat with a crashing unstoppable rhythm perceptible from a hundred million miles away. The New Vlast was a pounding anvil the sun itself could feel: it shook the drum-taut solar photosphere, the 6,000-degree plasma skin.

But no day will ever beat more strongly or echo more enduringly down the corridors of the coming millennia than this one day, and Engineer-Technician Mikkala Avril will play her vital part.

She pauses on the airfield apron, savouring the moment, fixing it in memory. The furnace weight of the sun’s heat beats on her face and shoulders and back. Hydrogen fusing into helium at a steady burn. She feels the remnants of the solar wind scouring her cheeks and screws her eyes against the bleach and glare. The air tastes of bitter herb and dusty cinder, of hot steel and of the sticky dust-streaked asphalt that peels noisily away from the soles of her shoes at every step. Breathing is hard labour.

Chaiganur is a scrub of desert steppe, baked dry under the rainless shimmering sky, parched to the far horizon. Flatness is its only feature. The dome of the sky is of no colour, the sun swollen and smeared across it, and the steppe is a whitened consuming lake bed of silent fierce unwatchable brightness. Nothing rises more than a few inches above the crumbling orange-yellow earth and the low clumps of coarse grey grass, nothing except pylons and gantries and hangars and scattered blockhouses: only they cast hot blue shadows. Miles to the south lies the shore of an ancient sea, and when the hot breeze blows it brings to Chaiganur a new covering of salty corrosive grit: ochre dust, clogging nozzles and caking surfaces.

The workers at Chaiganur put scorpions in bottles and watch them fight.

Throughout the two-hour flight from the Kurchatovgrad Barracks, Mikkala Avril had studied the technical manual, memorising layouts and procedures she already knows by heart. The night-duty clerk woke her in the early hours of the morning, agog with news, his part in her drama. A telephone call had come: instructions to go instantly to Chaiganur, transport already waiting. Her principal, Leading Engineer-Technician Filipov, had been taken suddenly and seriously ill and she–she, Mikkala Avril, there was no mistake, there was no one else, none qualified–was required immediately to take Filipov’s place. Not an exercise. The thing itself.

As she put on her uniform she spared a thought for Filipov. He and his family would not be heard from again. Their names would no longer be spoken. It was a pity. Filipov had trained her well. Her success this day would be his final and most lasting contribution.

The plane bringing her to Chaiganur flew low. She watched through the window as they crossed the testing grounds and saw scars: the wide grey splash-craters of five years’ worth of atomic detonations, the fallen pieces of failed and exploded engineering, the twisted wreckage of spent platforms cannibalised from war-surplus bridges and pontoons. Half-buried chunks of stained concrete resembled the dry bones and broken tusks of dead giants.

Didn’t mammoths once walk this land? She might have heard that somewhere. Hadn’t someone–but who?–taken her once, a girl, to rock outcrops polished smooth by long-dead beasts (by the scraping of scurf and ticks from their rufous hairy sides). That might have happened to her, she wasn’t sure. Whatever. Nothing thrives now in all that flatness of stony rubbish but scorpions and rats and foxes and the sparse nomadic tribes with their ripe-smelling beards and scrawny horses.

The plane that brought her leaves again immediately, engines dwindling into sun-bleached silence. She heads for the control block, picking her way across pipes and thick cables that snake along the ground. She might be only one small component in the machine, one switch in the circuit, but she will execute her task smoothly, and that will matter. That will make a binary difference; that will allow the perfection of the most profound accomplishment of humankind. She will make no mistake. She will do it right.

Exactly one hour after the arrival of Mikkala Avril, a convoy sweeps at speed past the security perimeter of the Chaiganur cosmodrome trailing a half-mile cloud of dust. Three-and-a-half-ton armoured sedans–chrome fenders, white-walled tyres–doing a steady sixty. Motorcycle outriders and chase cars. They are heading straight for Test Site 61.

The sun-baked sedans carry the entire membership of the Central Committee of the New Vlast Presidium, and in one of the cars–no one is sure which, the bullet-proof windows are tinted–rides the President-Commander himself, General Osip Rizhin. Papa Rizhin, the great dictator, first servant of the New Vlast, coming to witness this greatest of triumphs and certify its momentousness with his presence.

Two jolting trucks bring up the rear. A sweating corps of journalists is tucked in among their movie cameras and their tape recorders. The men in the open backs of the trucks crook their arms in permanent angular shirt-sleeved salute, cramming homburgs, pork-pies, fedoras down tight on their heads against the hot wind of their passage. None but Rizhin knows what they are coming to see.

The party might have flown in to the cosmodrome in comfort but Rizhin refused to allow it, citing the presence among them of ambassadors from the new buffer states. We must never permit a foreigner to fly across the Vlast, he said. All foreigners are spies. That was the reason he gave, but his purpose was showmanship. He didn’t want his audience seeing the testing zones or getting any other clues. None among them, not even the most senior Presidium member, had any idea how far and how fast the project had progressed. And so they all rode for three days in a sweltering sealed train with perforated zinc shutters on the outside of the windows, and then in cars from the railhead, five hours across baking scrubland, to arrive red-faced and dishevelled at Test Site 61, where a cluster of temporary tin huts has been erected for the purpose of receiving them.

The temporary huts crouch in the shade of a two-hundred-foot tall, eighty-foot diameter, snub-nosed upright bullet of thick steel. The bullet is painted crimson with small fins near the base. The fins serve no functional purpose but Rizhin demands them for the look of the thing, to make it more like a rocket, which it is not.

The Vlast Universal Vessel Proof of Concept stands against its gantry, an ugly truncated stub, a blood-coloured thumb cocked at the sky, a splash of hot red glimmering in the glare of the sun.

Three time zones west of Chaiganur and eight hundred miles to the north, in the eastern outskirts of Mirgorod, a short train ride from the shore of Lake Dorogha, a woman in a shabby grey dress picks her way across a war-damaged wasteland.

Five years of reconstruction across the city have passed this place by, and the expanse of bomb craters and ruined buildings is much as she last saw it: tumbled brick-heaps, charred beams, twisted girders, tattered strips of wallpaper exposed to the sun. There are brambles now, nettles and fireweed and glossy grass clumps on slopes of mud, but otherwise nothing has changed. It is still recognisable.

The place she is looking for isn’t hard to find. She chose it well back then. It is a warehouse of solid blue brick, a bullet-scarred construction of blind walled arches and small glassless windows: roofless, but so it had been back then. During the siege this place had been contested territory: again and again the tanks of the Archipelago passed through and were driven back, and each time the warehouse survived. An artillery shell had taken a gouge from one corner, but the walls had stood. She’d used the upper windows herself for a week. It made a good place to shoot from when she was waging her private war, alongside the defenders of Mirgorod but not of them.

She crosses the open ground to the warehouse carefully, taking her time, moving expertly from cover to cover, using the protection of shell holes and bits of broken wall. There are no shooters to worry about now, only wasps and rats, nettles and thorns. Almost certainly there is no one here to see her at all, no faces in the overlooking windows, but it’s as well to take precautions. She mustn’t be noticed. Mustn’t be seen. The sound of the city is a distant hum. She is getting her dress dusty and mud-stained, but she has anticipated that. She carries a change of clothes in the canvas bag slung on her back. She is nearly forty years old, but she remembers how to do this. She was good at it then and she is good at it still.

Inside the warehouse the stairs to the cellars are as she remembers them. She has brought matches and a taper, but she doesn’t need them. She finds her way through the darkness, familiar as yesterday, by feel. Nothing has changed. It is possible that no one has been here at all since she left it for the last time on the day the war’s tide turned and the enemy withdrew.

She crouches at the far wall and runs clenched, ruined fingers along the low niche, touching brick dust and stone fragments and what feels like a couple of iron nails. For a moment she cannot find what she is looking for and her heart sinks. Then she touches it, further back than she remembered but still there. Her fingertips brush against an edge of dusty oilcloth.

Carefully she hooks the bundle out from the niche. It’s narrow and four feet long, bound with three buckled straps cut from an Archipelago officer’s backpack. The touch and heft of it–about twelve pounds weight in total, she estimates without thinking–brings memories. Erases the years between. She notices that her hands are trembling, and she pauses, takes a breath, centres herself and clears her mind. The trembling stops. She hasn’t forgotten the trick of that, then. Good.

In the blackness of the warehouse cellar, working by feel, she brushes the grit and dust from the oilcloth bundle and wraps it in the towel she stole before dawn that morning from a communal washroom. (The towel is a child’s, faded pink with a pattern of lemon-yellow tractors, the most innocuous and suspicion-disarming thing she could find. If she’s stopped and searched on the way back, it might just work. Camouflage and misdirection. Though she doesn’t expect to be searched: she’ll be just one more thin drab widow lugging a heavy bag. Such women are almost invisible in Mirgorod.)

She stows the towel-wrapped bundle in the canvas bag, hooks the bag on her shoulder and climbs back up towards the narrow slant of dust-filled sunlight and the morning city.

In a temporary hut at Chaiganur Test Site 61 the ministers of the Central Committee of the Presidium and the other dignitaries assemble to hear a briefing from Programme Director Professor Yakov Khyrbysk. The room is unbearably hot. Dry steppe air drift s in through propped-open windows. Khyrbysk’s team has mustered tinned peach juice and some rank perspiring slices of cheese.

President-Commander of the New Vlast General Osip Rizhin fidgets restlessly in the front row while Khyrbysk talks. He has heard before all that Khyrbysk has to say, so he is working through a pile of papers in his lap, scrawling comments across submissions with a fountain pen. Time moves on, time must be used. Big fat ticks and emphatic double side-linings. Approved. Not approved. Yes, but faster! Why so long? Do it now! Rizhin likes to draw wolves in the margins. I am watching you.

He listens with only half an ear as the Director runs through his spiel: how the experimental craft will drop atomic bombs behind itself at the rate of one a second and ride the shock waves upwards and out of the planetary gravity well. How the ship is not small, as space capsules are imagined to be, but built large and heavy to withstand the explosive forces and suppress acceleration to survivable levels.

‘Vlast Universal Vessel Proof of Concept weighs four thousand tons,’ he tells them, ‘and carries a fifteen-hundred-ton payload. She was designed and built by the engineers of the Bagadahn Submarine Yard.’

He tells them how the explosions generate temperatures hotter than the surface of the sun, but of such brief duration they do not harm the pusher plate. How Proof of Concept is equipped with two thousand bombs of varying power, and the mechanism for selecting the required unit and delivering it to the ejector is based on machinery from an aquavit-bottling factory. That gets a chuckle from the back of the room.

The ministers of the Presidium play it cautiously. They keep their expressions carefully impassive, neutral and unimpressed, but inwardly they are making feverish calculations. Who does well out of this, and who not? How should I react? Whose eye should I catch? What does this mean for me?

Rizhin listens with bored derision to their sceptical questioning and Khyrbysk’s patient answers. So that thing outside is a bomb? No, it is a vessel. It carries a crew of six. How can explosions produce sustained momentum not destruction? It is no different in principle to the operation of the internal combustion engine of the car that brought you here. Is the craft not destroyed in the blast? Will the crew not be killed? I hear there is no air to breathe in space and it is very cold.

Fucking doubters, thinks Rizhin. Do they think I’d have wasted time on a thing that doesn’t fucking work?

But he listens more carefully as Khyrbysk explains how each bomb is like a fruit, the hard seed of atomic explosive packed in a soft enclosing pericarp of angel flesh. The angel flesh, instantly transformed to superheated plasma in the detonation, becomes the propellant that drives against the pusher plate.

‘We call the bombs apricots,’ says Khyrbysk, which gets another laugh and a flurry of scribbling.

Rizhin is deeply gratified by this exploitation of angel flesh. Since Chazia died at Novaya Zima and the cursed Pollandore was destroyed, he’s heard no more from the living angel in the forest. No falling fits. No disgusting invasions of his skull. All the angel flesh across the Vlast has fallen permanently inert, and the bodies of the dead angels are nothing now but gross carcasses, splats on his windshield, and he is moving fast. Even the mudjhiks have died. Nothing more than slumped and ill-formed statuary, Rizhin had them ground to a fine powder and shipped off to Khyrbysk’s secret factories. Yes, even the four that stood perpetual guard at the corners of the old Novozhd’s catafalque.

‘And now,’ Khyrbysk is saying, ‘we will retire to the cosmodrome and watch the launch from a safe distance.’

But there is a brief delay before they can leave. Rizhin must honour the cosmonauts. A string quartet has been rustled up from somewhere, and sits under the shade of a tarpaulin playing jaunty martial music: ‘The Lemon Grove March’.

The cosmonauts, three men and three women, march up onto the makeshift podium and stand in a row, fine and tall and straight in full-dress naval uniform in the roaring blare of the sun. Brisk apple-shining faces. Scrubbed, clear-eyed, military confidence. Rizhin says a few words, and shutters click and movie cameras whirr as he presents each cosmonaut in turn with a promotion and a decoration. Hero of the Vlast First Class with triple ash leaves. The highest military honour there is. The cosmonauts shake Rizhin’s hand firmly. Only one of them, he notices, looks uneasy and doesn’t meet his eye.

‘Nervous, my friend?’ he says.

‘No, my General. The sun is hot, that’s all. I don’t like formal occasions. They make me uncomfortable’

‘Call me brother,’ says Rizhin. ‘Call me friend. You are not afraid, then?’

‘Certainly not. This is our glory and our life’s purpose.’

‘Good fellow. Your names will be remembered. That is why the cameras and all these stuffed shirts have turned out for you.’

On the way back to their cars the dignitaries stare at the stubby red behemoth glowing in the sun: the Vlast Universal Vessel Proof of Concept with its magazine of two thousand apricots, rack upon rack of potent solar fruits.

Rizhin is walking fast, oblivious to the heat, eager to be on the move. Secretary for Agriculture Vladi Broch breaks into a waddling jog to catch up with him. Broch’s face is wet with perspiration. Rizhin flinches with distaste.

‘Triple ash leaves?’ says Broch. ‘If you give them that now, what will you do for them when they come back?’

‘When they come back?’ says Rizhin. ‘No, my friend, there is no provision for coming back. That is not part of the plan.’

‘Ah,’ says Broch. ‘ Oh. I see. Of course. But… so, how long will they last?’

Rizhin shrugs. ‘Who knows?’ He claps Broch on the shoulder. ‘We’ll find that out, won’t we, Vladi Denisovich? That is the method of science. You should get friend Khyrbysk to explain it to you some time.’

In the control room at Chaiganur the tannoy broadcasts radio exchanges with the cosmonauts. From the edges of the room the whirring movie cameras follow every move with long probing lenses, hunting for the action, searching for the telling expression.

‘T minus 2000, Proof of Concept. How are you doing?’

All is good, Launch. Very comfortable.

The cosmonaut’s voice grates, over-amplified and crackling.

‘I remind you that after the one-minute readiness is sounded, there will be six minutes before you actually begin to ascend.’

Understood, Launch. Thank you.

The cosmonauts have nothing to do. No function. No control over their vessel unless and until the launch controller flicks the transfer switches. Their windows are blind with heavy steel shutters, which they will take down once they reach orbit.

If they reach orbit.

The last of the ground crew is already three miles away, racing for the safety perimeter in trucks.

And so the cosmonauts wait, trussed on their benches, separated by the thickness of two heavy bulkheads and a storage cavity from a warehouse of atomic bombs. They are sealed for ever inside the nose of Proof of Concept, locked in by many heavy bolts that will never be withdrawn, and the ship beneath them is alive with rumble and vibration, the whine of pumps, the whisper of gas nozzles, the thunk and clank of unseen mechanisms whose operations the cosmonauts barely understand.

The technicians who actually control Proof of Concept are ten miles away inside a low concrete caisson, a half-buried blockhouse built with thick and shallow-sloping outer walls to deflect blast and heat up and over the top of the building. Not quite twenty in number, the technicians occupy a semicircle of steel desks facing inwards towards the launch controller at his lectern. They lean forward into the greenish screens of their cathode readout displays, flicking switches, twisting dials, turning the pages of their typescript manuals. They wear headphones and mutter into their desk microphones. Quiet purposeful conversations. For them this is no different from a hundred test firings: everything is the same except that nothing is the same.

Behind the controller a wide panoramic window of sloping glass gives a view across the flatness of the steppe. The assembled dignitaries and journalists sit in meek rows between the controller and this window on folding chairs, the sun on their backs, not wanting to cause a distraction. In something over thirty minutes they will turn to watch Proof of Concept climbing skyward to begin her journey. They have been issued with black-lensed spectacles for the purpose. For now they clutch them in their laps and observe the technicians, alert for any hint of anxiety in the muted voices. They watch for the flicker of red lamps on consoles, the blare of an alarm, a first indication of disaster. More than one of them wants to see failure today: a grievous humiliation for Director Khyrbysk and his protectors could mean great advantage for them. Others are cold-sweating terrified of the same outcome: if Khyrbysk’s star wanes, theirs will tumble and crash all the way to a hard exile camp or a basement execution cell.

Guests and technicians alike smoke relentlessly.

President-Commander Osip Rizhin has not yet arrived in the control room. An empty chair waits for him between Khyrbysk and the chief engineer, whose name is never mentioned for he is a most secret and protected national resource.

‘T minus eighteen hundred, Proof of Concept.’

Thank you, Launch.

‘You are all well?’

There is an implication in the question. The captain of cosmonauts carries a pistol in case of… arising human problems. The psychology of each cosmonaut has been thoroughly and expertly examined, but the effects on emotional stability of massive acceleration, prolonged weightlessness and extreme separation from the planetary home are unknown. Every member of the crew is equipped with a personal poison capsule. The foresighted bureaucratic kindness of the Vlast.

We’re all good, Launch. We could do with some music to pass the time.

‘We’ll look into that, Proof of Concept.’

The launch controller’s gaze sweeps across the technicians at their workstations and settles on Engineer-Technician 2nd Class Mikkala Avril. He raises an eyebrow and she stands up.

Five minutes later, hurrying back down the passageway from the recreation room with an armful of gramophone records, hot with anxiety to return to her console, Mikkala Avril runs slap into men in dark suits armed with sub-machine guns. Rizhin’s personal bodyguard, walking twenty-five steps ahead of the President-Commander himself. Papa Rizhin–Papa Rizhin! In person!–is bearing down on her.

Terrified, the young woman in whom beats the heart of the New Vlast presses herself flat against the wall and shows her empty hands, the stack of records tucked hastily under her left arm. She has been taught what to do in such an extremity. Always look him in the eye, but not too much. Stay calm at all times, be respectful, answer all enquires with humour and firmness, above all conceal nothing.

Mikkala Avril stands against the wall, back straight, eyes forward. The gramophone records are slipping slowly from the awkward sweaty grip of her elbow. Any moment now they will fall to the floor and there is nothing she can do about it. Desperately she squeezes them tighter between arm and ribs, but it only seems to make the situation worse.

Papa Rizhin glances at her as he passes and notices her confusion. Stops.

‘Are you working on the launch?’

His voice is recognisable from his broadcasts but it is not the same. It is surprisingly expressive, with the tenor richness of a good singer. Up close his cheeks are scattered with pockmarks like open pores, something which is not shown in portraits: the legacy of a childhood illness, perhaps.

‘Yes, General,’ she says.

‘What is your task?’

‘To monitor the telemetry of the in-atmosphere flight guidance systems, General. The vessel carries small rockets to correct random walk—’

‘Yes,’ says Rizhin, interrupting her. ‘Good. You are young for this responsibility. And is all in order? Is there any concern?’

‘No, General. None. All is in perfect order.’

Inevitably the sweat-slicked gramophone records choose this moment to fall slap in a heap at Rizhin’s feet.

Mikkala Avril stares blankly at the wreckage: the titles of the musical pieces in curling script on the glossy sleeves; the monochrome photo graphs of mountains and lakeside trees. She feels her face turning purple.

Rizhin shows no reaction and does not look down.

‘What is your name?’ he says.

‘Avril, General. Engineer-Technician 2nd Class.’

‘That is good then. Avril. I will remember the name. The New Vlast needs young engineers; it is the noblest of professions. You are the brightest and the best.’

He glances at last at the fallen records and smiles with this eyes.

‘Youth must not fear General Rizhin,’ he says. ‘He is its friend.’

When he’s out of sight she crouches down to scrabble for the records. Shit, she mutters under her breath over and over again. Shit. Shit. Shit.

‘T minus twelve hundred, Proof of Concept. We have some music for you.’

A syrupy dance tune begins to play over the tannoy: ‘The Garment Workers of Sevralo’.

Yakov Khyrbysk groans inwardly and glares at the launch controller. Must we? He glances at his watch and wonders where Rizhin has got to. Wandered off, sniffing out buried corpses. It makes Khyrbysk uneasy, and he is edgy enough already.

On the other side of Rizhin’s empty seat, the chief engineer is leaning forward, long dark-suited limbs gathered in tight about him. He steeples his long slender fingers. The fingernails are ruined: blackened sterile roots that will not grow again. The chief engineer (whose name on Rizhin’s order is never spoken now, not even by himself) survived five years in prison camps before Khyrbysk found him and managed to fish him out. He hunches now like a bird on a steep-gabled rooftop, watching in silence. He has the pallid complexion of a man who lives his life underground and takes no exercise, but he is hot with energy. It stares from his eyes. Fierce, stark intelligence. Such energy would have burned through a weaker person long ago, but the chief engineer’s constitution is a gift of nature. It is hard to tell how old he is, a young forty or a harrowed twenty-five. His hair is cut short at the back and the sides like a boy’s.

The convoy of sedans waits outside, lined up, engines running, ready to race Rizhin and the dignitaries to safety in case of disaster. Khyrbysk wonders if someone has thought to issue the drivers with dark glasses. He is considering checking on this when Rizhin arrives and takes his seat. Kicks back, legs stretched out, reclining.

‘Today we start the engine of history, Yakov,’ says Rizhin. ‘Today we blow open the door on our destiny.’ He fishes for a paper packet of cheap cardboard cigarettes and lights one, drawing the rough smoke deep into his lungs. ‘Those are good phrases. They have a smack to them. I’ll use them in my speech.’ He exhales twin streams through his nose. ‘No problems, eh, Yakov? No fuck-up?’

‘We’ve made test firings every week for the last three months.’

So many tests that the Chaiganur desert is scorched and glassed and pitted for hundreds of miles in every direction, the landscape pocked with scar-pits that show the corps. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...