- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

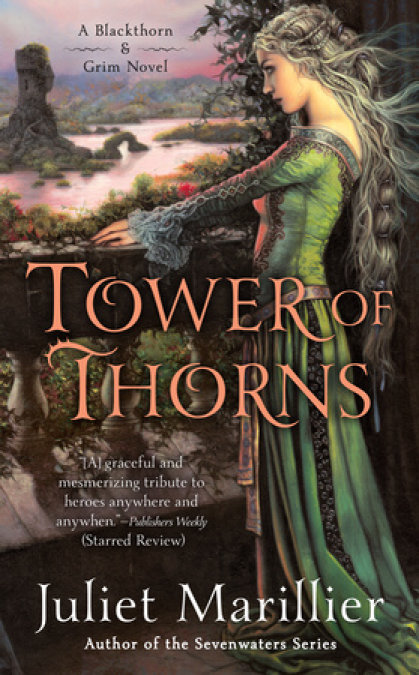

Award-winning author Juliet Marillier’s “lavishly detailed”(Publishers Weekly) Blackthorn & Grim series continues as a mysterious creature holds ancient Ireland in thrall...

Disillusioned healer Blackthorn and her companion, Grim, have settled in Dalriada to wait out the seven years of Blackthorn’s bond to her fey mentor, hoping to avoid any dire challenges. But trouble has a way of seeking them out.

A noblewoman asks for the prince of Dalriada’s help in expelling a creature who threatens the safety and sanity of all who live nearby from an old tower on her land—one surrounded by an impenetrable hedge of thorns. With no ready solutions to offer, the prince consults Blackthorn and Grim.

As Blackthorn and Grim put the pieces of this puzzle together, it’s apparent that a powerful adversary is working behind the scenes. Their quest soon becomes a life-and-death struggle—a conflict in which even the closest of friends can find themselves on opposite sides.

Release date: November 3, 2015

Publisher: Ace

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Tower of Thorns

Juliet Marillier

Also by Juliet Marillier

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Character List

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

This list includes some characters who are mentioned by name but don’t appear in the story.

Oran: prince of Dalriada

Flidais: Oran’s wife

Donagan: Oran’s companion

Deirdre: Flidais’s chief handmaid

Nuala: maidservant

Mhairi: maidservant

Seanan: man-at-arms

Blackthorn: wisewoman, formerly known as Saorla (seer-la)

Grim: her companion

Emer: (eh-ver) Blackthorn’s young assistant

Ruairi: king of Dalriada; Oran’s father

Eabha: queen of Dalriada; Oran’s mother

Sochla: Eabha’s sister

Master Caillín: court physician

Rodan: man-at-arms

Domnall: senior man-at-arms

Eoin: man-at-arms

Lochlan: man-at-arms

Geiléis: (ge-lace, hard g) the Lady of Bann

Senach: steward

Dau: (rhymes with now) manservant

Cronan: manservant

Caisín: (ka-sheen) seamstress, married to Rian

Onchú: senior man-at-arms

Donncha: man-at-arms

Rian: man-at-arms, married to Caisín

Mechar: man-at-arms (deceased)

Ana: a cottager

Fursa: her baby son

Father Tomas: head of the monastic foundation

Brother Dufach: one of the monks

Brother Fergal: gardener

Brother Ríordán: (reer-dawn) head archivist

Brother Dathal: (do-hal) assistant archivist

Brother Marcán: infirmarian

Brother Tadhg: (t¯ıg) a tall novice

Brother Eoan: (ohn) keeper of pigeons

Brother Galen: scribe and scholar (deceased)

Bathsheba: his cat (deceased)

Brother Conall: a novice

Lily: a young noblewoman

Ash (Brión): a young nobleman

Muiríol: (mi-reel) Lily’s maidservant

Mathuin: chieftain of Laois

Lorcan: king of Mide

Flannan: a traveling scholar

Ripple: Flannan’s dog

Conmael: a fey nobleman

Master Oisín: (a-sheen) a druid

Cass: Blackthorn’s husband (deceased)

Brennan: Blackthorn’s son (deceased)

Brother Gwenneg: an acquaintance from Geiléis’s past

Cú Chulainn: (koo hull-en) a legendary Irish hero

PROLOGUE

Geiléis

Rain had swollen the river to a churning mass of gray. The tower wore a soft shroud of mist; though it was past dawn, no cries broke the silence. Perhaps he slept, curled tight on himself, dreaming of a time when he was whole and hale and handsome. Perhaps he knew even in his sleep that she still kept watch, her shawl clutched around her against the cold, her gaze fixed on his shuttered window.

But he might have forgotten who she was, who he was, what had befallen them. It had been a long time ago. So long that she had no more tears to shed. So long that one summer blurred into another as the years passed in an endless wait for the next chance, and the next, to put it right. She did not know if he could see her. There were the trees, and the water, and on mornings like this, the mist lying thick between them. Only the top of the tower was visible, with its shuttered window.

Another day. The sun was fighting to break through; here and there the clouds of vapor showed a sickly yellow tinge. Gods, she loathed this place! And yet she loved it. How could she not? How could she want to be anywhere but here?

Downstairs, her household was stirring now. Someone was clanking pots, raking out the hearth, starting to make breakfast. A part of her considered that a warm meal on a chilly morning would be welcome—her people sought to please her. To make her, if not happy, then at least moderately content. It was no fault of theirs that she could not enjoy such simple pleasures as a full belly, the sun on her face, or a good night’s sleep. Her body was strung tight with waiting. Her heart was a constant, aching hurt in her chest. What if there was no ending this? What if it went on and on forever?

“Lady Geiléis?”

Senach tapped on the door, then entered. Her steward was a good servant, discreet and loyal. “Breakfast is ready, my lady,” he said. “I would not have disturbed you, but the fellow we sent to the Dalriadan court has returned, and he has some news.”

She left her solitary watch, following her man out of the chamber. As Senach closed the door behind them, the monster in the tower awoke and began to scream.

• • •

“Going away,” she said. “For how long?”

“King Ruairi will be attending the High King’s midsummer council, my lady.” Her messenger was gray-faced with exhaustion; had he traveled all night? His mead cup shook in his hands. “The queen will go south with him. They will be gone for at least two turnings of the moon, and maybe closer to three.”

“Who will accompany them? Councilors? Advisers? Friends and relations?”

“All the king’s senior councilors. Queen Eabha’s attendants. A substantial body of men-at-arms. But Cahercorcan is a grand establishment; the place will still be full of folk.”

“This son of King Ruairi’s,” she said. “The one you say will be looking after his father’s affairs while they’re gone—what manner of man is he? Of what age? Has he a wife?”

“Prince Oran is young, my lady. Three-and-twenty and newly married. There’s a child on the way. The prince does not live at Cahercorcan usually, as he has his own holding farther south. He is more a man of scholarship than a man of action.”

“Respected by his father’s advisers, those of them who remained behind?” A scholar. That might be helpful. “Is he a clever man?”

“I could not say, my lady. He’s well enough respected. They say he’s a little unusual.”

“Unusual?”

“They say he likes to involve all his folk in the running of household and farm. And I mean all, from the lowliest groom to the most distinguished of nobles. Consults the community, lets everyone have a say. There’s some at court think that odd; they’d sooner he just told folk what to do, as his father would.”

“I see.” Barely two turnings of the moon remained until midsummer. After the long, wearying search, the hopes dashed, the possibilities all come to nothing, she had been almost desperate enough to head south and throw herself at King Ruairi’s feet, foolish as that would have been. Common sense had made her send the messenger first, with orders to bring back a report on the situation at court. She had not expected anything to come of it; most certainly not this. Her heart beat faster; her mind raced ahead. The king gone, along with his senior advisers. The queen absent too. The prince in charge, a young man who would know nothing of her story . . . Could this be a real opportunity at last? Dared she believe it? Perhaps Prince Oran really was the key. Perhaps he could find her the kind of woman she had so long sought without success.

She’d have to ride for Cahercorcan soon—but not too soon, or she risked arriving before the king and his entourage had departed. It was the prince she needed to speak to, not his father. How might she best present her case? Perhaps this scholarly prince loved tales of magic and mystery. She must tell it in a way that would capture his imagination. And his sympathy.

She rose to her feet. “Thank you,” she said to the messenger. “Go to the kitchen; Dau will give you some breakfast. Then sleep. I’ll send for you later if I have further questions.” Though likely he had told all he knew. She’d sent him to the royal household in the guise of a traveler passing through and seeking a few nights’ shelter. There’d be limits to what a lad like him could learn in such a place. “Senach,” she said after the messenger was gone, “it seems that this time we have a real opportunity.” At last. Oh, at last! She had hardly dared to dream this might be possible. “You understand what this means?”

“Yes, my lady. You’ll be wanting to travel south.”

“I will, and soon. Speak to Onchú about an escort, will you? In my absence, you will be in charge of the household.”

“Of course, my lady.” A pause, then Senach added, “When do you plan to depart?”

“Not for a few days.” Every instinct pulled her to leave now, straightaway, without delay; any wait would be hard to bear. But they must be sure the royal party had left court. “Let’s say seven days. That should be long enough.”

“When might I expect you to return, my lady?”

Her lips made the shape of a smile, but there was no joy in her. She had forgotten how it felt to be happy. “Before midsummer. That goes without saying. Prepare the guest quarters, Senach. We must hold on to hope.” Hope, she thought, was as easily extinguished as a guttering candle on a day of spring storm. Over and over she had seen it tremble and die. Yet even now she was making plans again, looking ahead, seeing the way things might unfold. Her capacity to endure astonished her.

“Leave it to me, my lady. All will be ready for you.”

• • •

Later still, as her household busied itself with the arrangements—horses, supplies, weaponry—she climbed back up to the high chamber and looked out once more on the Tower of Thorns. All day its tenant had shouted, wailed, howled like an abandoned dog. Now his voice had dwindled to a hoarse, gasping sob, as if he had little breath left to draw.

“This time I’ll make it happen,” she murmured. “I swear. By every god there ever was, by the stars in the sky and the waves on the shore, by memory and loss and heartbreak, I swear.”

The sun was low; it touched the tower with a soft, rosy light that made a mockery of his pain. It would soon be dusk. There was just enough time.

With her gaze on that distant window, she began the nightly ritual. “Let me tell you a story.”

1

Blackthorn

I sat on the cottage steps, shelling peas and watching as Grim forked fresh straw onto the vegetable patch. Here at the edge of Dreamer’s Wood, dappled shade lay over us; the air held a warm promise of the summer to come. In the near distance green fields spread out, dotted with grazing sheep, and beyond them I glimpsed the long wall that guarded Prince Oran’s holdings at Winterfalls. A perfect day. The kind of day that made a person feel almost . . . settled. Which was not good. If there was anything I couldn’t afford, it was to get content.

“Lovely morning,” observed Grim, pausing to wipe the sweat off his brow and to survey his work.

“Mm.”

He narrowed his eyes at me. “Something wrong?”

A pox on the man; he knew me far too well. “What would be wrong?”

“You tell me.”

“Seven years of this and I’ll have lost whatever edge I once had,” I said. “I’ll have turned into one of those well-fed countrywomen who pride themselves on making better preserves than their neighbors, and give all their chickens names.”

“Can’t see that,” said Grim, casting a glance at the little dog as she hunted for something in the pile of straw. The dog’s name was Bramble, but we didn’t call her that anymore, only Dog. There were reasons for that, complicated ones that only a handful of people knew. She was living a lifelong penance, that creature. I had my own penance. My fey benefactor, Conmael, had bound me to obey his rules for seven years. I was compelled to say yes to every request for help, to use my craft only for good, and to stay within the borders of Dalriada. In particular, Conmael had made me promise I would not go back to Laois to seek vengeance against my old enemy. I’d known from the first how hard those requirements would be to live by. But my burden was nothing against that borne by Ciar, who had once been maidservant to a lady. For her misdeeds, she had been turned into a dog. Magic being what it was—devious and tricky—she had no way back.

“Anyway,” Grim went on, “it’s closer to six years now.”

“Why doesn’t that make me feel any better? It doesn’t seem to matter how busy I am, how worn-out I am after a day of applying salves and dispensing drafts and giving advice to every fool who thinks he wants it. Every night I dream about the same thing: what Mathuin of Laois did to me, and what I’ll do to him. And the fact that Conmael’s stupid rules are stopping me from getting on with it.”

“I dream about that place,” Grim said. “The stink. The dark. The screams. I dream about nearly losing hope. And when I wake up, I look around and . . .” He shrugged. “The last thing I’d be wanting is to go back. Different for you, I know.”

I wanted to challenge him; to ask if there weren’t folk who’d wronged him, folk he might care to teach a lesson to. Or folk who’d once loved him, who might still be missing him and needing him to come home. But I held my tongue. We didn’t ask each other about the past, the time before we’d found ourselves in Mathuin’s lockup, staring at each other across the walkway between the iron bars. A whole year we’d kept each other going, a year of utter hell, and we’d never shared our stories. Grim knew some of mine now, since I’d blurted it out on the day fire destroyed our cottage. How Mathuin of Laois had punished my man for his part in a plot against injustice. How he’d burned Cass and our baby alive, how he’d ordered his guards to hold me back so I couldn’t reach them. Grim knew the dark thing I carried within me, the furious need to see justice done. And Conmael knew. Conmael knew far more than anyone rightly should.

“Pea soup?” Grim’s voice broke into my thoughts.

“What? Oh. Seems a shame to cook them—they taste much better raw. But yes, soup would stretch them out a bit. I’ll make it.”

“Onion, chopped small,” he suggested. “Garlic. Maybe a touch of mint.”

“Trying to distract me from unwise thoughts?” I turned my gaze on him, but he was busy with his gardening again.

“Nah,” said Grim. “Just hungry. Looks like we might have company in a bit.”

A rider was approaching from the direction of Winterfalls. From this distance I couldn’t tell who it was, but the green clothing suggested Prince Oran’s household.

“Donagan,” said Grim.

The prince’s body servant; a man with whom we shared a secret or two. “How can you tell?”

“The horse. The white marking on her head. Only one like that in these parts. Star, she’s called.”

“You think the prince’s man will be happy to eat my pea soup?”

“Why not? I always am. Need to start cooking soon, though, or he won’t get the chance.” Grim laid aside his pitchfork and straightened up, a big bear of a man. “I’ll do it if you want.”

“You’re busy. I’ll do it.” Since I didn’t plan on standing out front like a welcoming party, I headed back into the house. Donagan was all right as courtiers went, but a visit from a member of the prince’s household generally meant some sort of request for help, and that meant saying yes to whatever it was, however inconvenient, because of my promise to Conmael. The most reasonable of requests felt burdensome if a person had no choice in the matter. If I was to survive seven years, I’d need to work on keeping my temper; staying civil. I only had four chances. Break Conmael’s rules a fifth time, and he’d put me straight back into Mathuin’s lockup as if I’d never left the place. That was what he’d threatened, anyway. Maybe he couldn’t do it, but I had no intention of putting that to the test.

Grim stayed outside and so did Donagan, whose arrival I saw between the open shutters. Once he’d tethered his horse, he leaned on the wall chatting as Grim finished his work with the pitchfork. That gave me breathing time, which I used not only to prepare the meal, but to put my thoughts in order. Step by small step; that was the only way I’d survive my time of penance. My lesson in patience. Or whatever it was.

• • •

Donagan had brought a gift of oaten bread. It went well with the soup. Dog sat under the table, feasting on crusts. Our guest waited until we had all finished eating before he came to the purpose of his visit. “Mistress Blackthorn, Lady Flidais has asked to see you, at your convenience.”

Nothing surprising about that, since Lady Flidais, wife to the prince, had been under my care since she’d first discovered she was expecting a child. The infant would not be born before autumn, and thus far the lady had remained in robust health. It was typical of her, if not of Donagan, that this had been presented as a request rather than as an order.

“I can come by this afternoon, if that suits Lady Flidais,” I told him. “I have one or two folk to visit in the settlement.” This had to be more than it seemed, or they’d have sent an ordinary messenger, not the prince’s right-hand man. “Is Lady Flidais unwell?”

“The lady is quite well. She has a request to make of you.”

There was a silence; no doubt Donagan felt the weight of our scrutiny.

“Can you tell us what it is?” I asked. “Or must this wait until I see her?”

“I’ve been given leave to tell you. King Ruairi and Queen Eabha will be traveling south soon for the High King’s council; they and their party will be away from Dalriada until well after midsummer. The king requires Prince Oran to be at court for that period, acting in his place.”

My thoughts jumped ahead to an uncomfortable conclusion. Lady Flidais and the prince both loved the peaceful familiarity of Winterfalls. I was quite certain they’d rather stay here than go to the king’s court at Cahercorcan, some twenty miles north. But although Oran was not your usual kind of nobleman, he wouldn’t refuse a request from his father, the king of Dalriada. And where Oran went, Flidais would be wanting to go too. The two of them were inseparable, like lovers in a grand old story. If they needed to be at court for two turnings of the moon or more, that meant . . . My guts protested, clenching themselves into a tight ball.

Grim said what I could not bring myself to say. “The lady, she’ll be wanting Blackthorn at court with her. That what you’re telling us?”

“Lady Flidais will explain,” Donagan said. “But yes, that is what she would prefer. Lady Flidais does not place a great deal of trust in the court physicians.” He fell silent, gazing into his empty soup bowl. Grim and I stayed quiet too. There was a long, long list of reasons why the prospect of going to court disturbed us; not all of them were reasons we could share with Donagan or indeed with Lady Flidais.

“Inconvenient, I know,” the king’s man said eventually, still not meeting my eye or Grim’s. “Your young helper would need to act as healer here in your absence. And . . . well, I understand this wouldn’t be much to your liking.” Now he glanced across at Grim. “Lady Flidais’s invitation extends to both of you. Since it’s for some time, there would be private quarters provided.”

“Invitation,” echoed Grim. “But not the sort of invitation a person says no to, coming from a prince and all.”

Donagan gave Grim a crooked smile. I had come to understand that he had a soft spot for my companion, though what exactly had passed between them during that odd time when Grim and I had stayed in the prince’s household I was not quite sure. I knew Grim had been in a fight and had hurt another man quite badly. I knew Donagan had helped get Grim out of trouble. So it was possible that Donagan realized how hard it was for Grim to sleep without me to keep him company—not the sort of company a man and a woman keep when they’re wed, more the company of a watchful friend, the same as we’d had when we were in that wretched place together, before I’d understood what friends were.

“True enough,” Donagan went on. “Still, I imagine you will say yes, not because you feel obliged to, but because Lady Flidais trusts you. And because you have her welfare at heart, as we all do.”

It was a pretty speech. No need to tell him that if I said yes, it wouldn’t be for that heartwarming reason, but because I was bound to it by Conmael. Court. Closed in by stone walls, surrounded by highbred folk quick to judge those they deemed their inferiors. I imagined myself embroiled in petty disputes with the royal physicians, who could only resent Lady Flidais’s preference for a local wise woman over their expert and scholarly selves. Court, where every single activity would be subject to some sort of ridiculous protocol. Morrigan’s curse! I’d found it hard enough staying in the prince’s much smaller establishment. Grim would loathe it. And what about Conmael and our agreement? He’d ordered me to live at Winterfalls, not at Cahercorcan. So complying with one condition of my promise would mean breaking another. A pox on it!

I rose to my feet. “Thank you for bringing the message. I have some herbs to gather before I head over to the settlement, but please tell Lady Flidais she can expect me around midafternoon.” I thought I did an excellent job of sounding calm and unruffled, but the look Grim gave me suggested otherwise.

“How soon?” he asked Donagan. “When’s the king leaving?”

“At next full moon. It’s a long journey to Tara, made more challenging by the fact that Mathuin of Laois is stirring up trouble in that region. And the king will want Prince Oran settled at court before he leaves.”

“Doesn’t give us long,” Grim said. His hands had bunched themselves into fists.

“You’ll be offered all the assistance you need for the move. Horses, help with packing up, arrangements put in place so young Emer can continue to provide a healer’s services to the community.”

“Emer’s been under my guidance for less than a year,” I protested. “She may be quite apt, but she can’t be asked to step into my place. It’s too much to expect.”

Donagan smiled. “I’m sure a solution will be found. Lady Flidais will discuss that with you. Now, I can see you are both busy, so I will make my departure.”

When he was gone, we sat staring at each other over the table, stunned into silence. After a while Grim got up and started gathering the bowls.

“Court, mm?” he said.

“Seems so. But what if Conmael says no?”

“Why would he?”

“The promise. Go to Winterfalls. Quite specific.”

“Then you tell Lady Flidais the truth,” Grim said.

“What, that the wise woman she trusts with her unborn child is actually a felon escaped from custody? That the only reason I help folk is because I have no choice in the matter? That the person I answer to is not even human?”

Grim fetched a bucket, took a cloth, wiped down the table. He spooned the leftover soup into a bowl for Dog. “Thing is,” he said, “she knows you now. She’s seen what kind of person you are. She’s seen what you can do. That’s why she trusts you; that’s why the prince trusts you. And you did get them out of a tight corner.”

“You mean we did.”

“Something else too,” said Grim. “Escaped felons. We may be that, and if we went south we might find ourselves thrown back in that place or worse. But Lady Flidais is hardly going to take Mathuin’s side. He’s her father’s enemy.”

The thought of telling Flidais the truth—of telling anyone—made me feel sick. “Trust me,” I said, “that is a really bad idea. What lies in the past should stay there. I shouldn’t need to tell you that. Let word get out about who we are and where we came from, and that word can make its way back to Mathuin.”

“Mm-hm.” He poured water from the kettle into the bucket and started to wash the dishes. After a while he said, “Why don’t you ask him, then? Conmael?”

“What, you think he’s going to appear if I go out there and click my fingers? I need to know now, Grim. Before I go and see Flidais.”

“Mm-hm.” He looked at me, the cloth in one hand and a dripping platter in the other. “What were the words of it, the promise you made to the fellow? Was it live at Winterfalls, or was it only live in Dalriada?”

I thought about it: the night when I’d been waiting to die, the terrible trembling that had racked my body, the way time had passed so slowly, moment by painful moment, Grim’s presence in the cell opposite the only thing that had stopped me from trying to kill myself. Then the strange visitor, a fey man whom I’d never clapped eyes on before, and the offer that had saved my life.

“I’m not sure I remember his exact words. One part of the promise was that I must travel north to Dalriada and not return to Laois. That I mustn’t seek out Mathuin or pursue vengeance. Then he said, You’ll live at Winterfalls. Or, You must live at Winterfalls. He told me that the prince lived here, and that the local folk had no healer. And that we could live in this house; he was specific about the details.”

“Maybe you don’t need to ask him,” said Grim. “Isn’t part of the promise about doing good? Looking after Lady Flidais, that’s doing good. Sweet, kind lady, been through a lot. And her baby might be king someday. If it’s a boy.”

“Some folk might say a future king would be better served by a court physician.”

“Lady Flidais doesn’t want a court physician,” Grim said. “She wants you.”

“Why are you arguing in favor of going? You’ll hate it even more than I will.”

“Be sorry to leave the house. And the garden. Just when we’ve got it all sorted out.” Grim spoke calmly, as if he did not care much one way or the other. His manner was a lie. It was a carapace of protection. He had become expert at hiding his feelings, and only rarely did he slip up. But I knew what must be in his heart. He had spent days and days fixing up the derelict cottage when we first came to Dreamer’s Wood. He had labored over both house and garden until everything was perfect. Then the cottage had burned down, and he had done it all over again. I wasn’t the only one who would find going away hard. “But it’s not forever,” Grim said. He tried for a smile but could not quite manage it. “Lads from the brewery can keep an eye on the place. Emer could drop in, make sure things are in order.”

I s

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...