- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

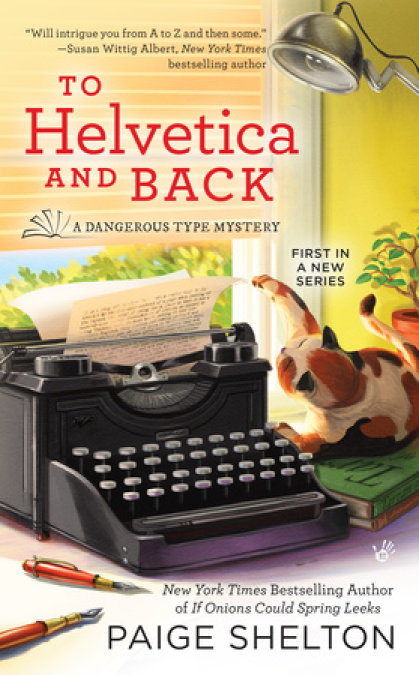

Star City is known for its slopes and its powder. But nestled in the valley of this ski resort town is a side street full of shops that specialize in the simple charms of earlier eras. One of those shops is the Rescued Word, where Chester Henry and his adult granddaughter Clare lovingly repair old typewriters and restore old books. Who ever thought their quaint store would hold the key to some modern-day trouble?

When a stranger to town demands they turn over an antique Underwood typewriter they're repairing for a customer, Clare fears she may need to be rescued. A call to the police scares the man off, but later Clare finds his dead body in the back alley. What about a dusty old typewriter could possibly be worth killing for?

Release date: January 5, 2016

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

To Helvetica and Back

Paige Shelton

Acknowledgments

Praise for the Novels of New York Times Bestselling Author Paige Shelton

Berkley Prime Crime titles by Paige Shelton

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

1

“The trouble is with the ‘L.’ Do you have any idea how important an ‘L’ is?” Mirabelle said as we peered in at the old black Underwood No. 5.

“I do,” I said as I wiped one hand over my leather work apron. I didn’t think my fingers were dirty, but I usually had ink on me somewhere.

I reached into the back of the old Subaru and pressed down on the “L” key, feeling no pressure and seeing no movement. “It seems that the type bar has detached.”

“Can you fix that?” Mirabelle said.

Mirabelle Montgomery was one of our more frequent customers. She’d been one of my grandfather’s very first customers when he opened his shop, The Rescued Word, almost fifty-five years earlier. Back then, she’d been wildly independent, writing scandalous stories on her already-half-a-century-old and classic Underwood No. 5 typewriter that she sold to even more scandalous magazines; that is, when she wasn’t carving powder on the slopes, taking on moguls and black diamonds like the fearless skier she’d been.

Mirabelle and my grandfather had formed a fast friendship, and though he had also been a fearless and accomplished skier, he often stated that he’d never been as good as Mirabelle. Chester, my grandfather’s name and what he wanted everyone including his grandchildren and great-grandchild to call him, had started his career by fixing typewriters. Back in 1960 when he’d just turned twenty-two and was already a father of two, he’d known he had to find a way to earn an income, so he started a business. He had no idea that his skills would transform over the years and turn The Rescued Word into the rare and unusual business it had become. He’d been able to keep up with the changing times fairly well—in between the days spent on the slopes and along with his manual-typewriter repair skills, he’d taught himself how to restore old books to their former glory. He’d built his own printing press—one that was a “bona fide Gutenberg replica,” or so he often said, after which he’d add some official-sounding lingo, as if an esteemed organization had given him the replica stamp of approval. Somewhere along the way, I figured out that no official experts had given the press any sort of notice at all, but it truly was an amazing machine.

Chester could even repair ink pens, the kind people spent real money for, the kind that were sought out when someone felt like they wanted to write something important or insightful. When I’d first started working with him at The Rescued Word, I’d been most surprised by how many people loved their pens. I preferred the throwaway variety myself, and I certainly noticed Chester’s looks of perplexed dismay when I pulled out my BIC or Paper Mate, though he never said a word. When he added the sale of fine paper and modern-day writing instruments to his offerings, he created a business that was truly built to last.

“I can definitely fix that,” I said to Mirabelle.

“Any chance I could get it back tomorrow?” Mirabelle said. “I have a letter for my grandson Miles. Oh, and I’ll need more of that blue paper too. I can get that today though.”

“You bet. I’ll get this back to you by tomorrow,” I said. I could, but it would mean working a little late, which was not a problem when it came to doing something for Mirabelle. I had to finish some work on a book that was due in the morning, but the printer was ready to go and the type blocks were in place.

“Oh, thank you, dear,” she said as she placed a crooked, wrinkled finger gently on the back paper table of the typewriter. “This old thing is like a friend, a constant companion. I don’t write stories anymore, but my grandbabies love receiving my typed letters. I would hate to disappoint Miles if my latest note wasn’t sent in a timely manner.”

“I understand. And fortunately, you’re not the only one who loves these old machines.”

“No? Gosh, most of the time I feel like I’m a dinosaur, a dying breed.” She laughed.

“Not even close, Mirabelle. Some still like to write on old typewriters, and some just like to have them on display, but in working order. Nope, you’re not the only one. This is, by the way, a very happy thing for The Rescued Word.”

“Business is good, then?” she asked, her penciled-on eyebrows lifting above her thick glasses.

“Well, fortunately we do a little more than fix typewriters, but, yes, business is good.”

“That’s wonderful to hear. Chester and I talk about every manner of thing, but never business. I worry about all of you over here. Bygone Alley is such a wonderful place. I’d hate to see anyone leave,” Mirabelle said.

“I think we all stay pretty busy,” I said.

The fairly level street that jutted off the steep slope of Main Street had long ago been affectionately named Bygone Alley for the old-time stores it held. Along with The Rescued Word, there was a yarn store with a couple looms, a beeswax candle store, a pocket-watch repair shop, a diner/cafe with a soda fountain, and the place where Professor Anorkory Levena taught Latin to people who actually paid him to learn the old, dead language. Though most of the services of those in Bygone Alley were from an earlier time and had been forgotten by many, all of us were still going strong, or strong enough.

I reached into the back of the Subaru and hefted out the almost ten pounds of Underwood. The No. 5s had at one time been the best of the best and used almost everywhere a typewriter was needed. They’d been known for many things, but they’d always been too big to lug around much, even if they had been called “portable.”

I knew that Mirabelle’s decades-old Subaru had logged about seventy thousand miles, because other than a few times a year to Salt Lake City, she only drove to a couple nearby places. She lived around the corner from Bygone Alley, on the street than ran along the non–Main Street side, and though the grocery store was at the bottom of a steep hill and around a tight S-turn, it was not far away. She’d also spent forty-five years working at the Star City Bank and Trust, but she’d walked to work every day. It had been an easy commute as she’d gone to and from the bank’s Main Street location via Bygone Alley, waving to us every morning or joining Chester for coffee if she had the time.

I supported the typewriter with both arms as Mirabelle closed the rear hatchback of the car, stepped up to the sidewalk, and opened the front door of The Rescued Word, signaling me to go in first.

When my grandfather purchased the two-story brick building, it had been empty for a few years, but before that it had been home to the Star City Silver Mining Company, a company that had flourished in the late 1800s and early 1900s because of the vast amounts of silver that had been found in the mountains around the mining town now turned skiers’ paradise. The first floor of the front part of the store was one big space that was filled with handmade wood shelving. The floors were also wood, original with plenty of long-ago-made scratches and marks to prove it. The walls were simple, now painted a soft blue where they weren’t covered by shelves, either the shelves that Chester had built to hold the different types of paper we sold, or the now-antique shelving from the days of the mining company.

The mining company shelves extended down the middle of both of the sidewalls and were protected by ornately carved wooden doors depicting scenes of the beautiful and mountainous country and wildlife around Star City. The doors were works of art, and we’d had plenty of customers visit who just wanted to take pictures of the carved doors. We welcomed them in, and if Chester was in the mood, he’d come out and tell the visitors a story about the doors. He made up a different story every time. He figured he was just giving the visitors something fun to think about; I thought he’d probably get in trouble someday for his fibs, but he didn’t seem to be concerned.

Filling the shelves were papers and note cards and envelopes of varying sizes, colors, and designs. Things were organized by color, and in some instances by complementary colors, like dark forest green and red. Or silver and gold. We had so many different animal note cards that we’d had to reorganize them by baby animals, adult animals, and then even further by which country they inhabited. Giraffes could be found on the Africa shelves, both under the baby animal and adult animal sub-categories.

There were windows along the top of the side walls that lit the entire space as the sun rose on one side and set on the other, finally slipping away every day behind one or another mountaintop, depending upon the time of the year. We had some light fixtures on the ceiling above but typically only turned them on in the late afternoon during the winter. Most of the time our cat, Baskerville, sat somewhere atop a set of shelves. He was there today, on the west side, enjoying the late-morning sun coming in the east windows. He’d move over to the other side soon.

The petite but surly calico meowed a suspicious greeting as he looked down upon us.

“Hello, kitty,” Mirabelle said. “I don’t think that cat likes me.”

“Baskerville doesn’t like many people,” I said as I eyed the cat that I adored despite how he might feel about me or anyone else. He was the offspring of the very first calico who’d roamed the store. Arial had been my friend and companion whenever I’d visited The Rescued Word, my après ski buddy who’d sat with me while I drank hot chocolate and watched Chester either fix or print something.

Though I’d taken to skiing just like almost everyone else in Star City, I’d been the adolescent cursed with braces and glasses and wild, curly hair that went every direction except the right one. Chester, Arial, and the warm hot chocolate were my best friends for a long time. I still wore glasses, but the braces were long gone, and my curls had been tamed by some products that did what they promised.

Back then I had no idea that fixing typewriters, restoring books, printing things, and selling beautiful papers and pens would become my career. I just thought I was having fun. Arial had been a wonderful and loving cat. She had no idea that her son would turn out grouchy and misanthropic. I’d always love and care for Baskerville, though, if only because Arial would appreciate the effort.

Though Chester had built most of the non-mining-company wood shelves inside the store, my brother and I had built the two shorter shelves that took up the middle of the space. The shelves had taken us a long time to build, mostly because he’d been sixteen and I’d been six, and neither of us had the patience needed to finish such a project quickly, but Jimmy and I were still proud of our handiwork.

The paper products we sold were imported from all over the world. Paper was important. The way ink moved over the paper was important. Ink itself was probably the most important thing of all. Jimmy and I had a game we played—Chester’s seven degrees of ink separation. Everyone and everything could be tied to ink in seven moves or less. Ink was somehow more important than blood; well, to Chester, at least.

The front portion of the store also displayed finer writing instruments and Chester’s favorite pencil, the only one he’d ever use. Trusty No. 2 pencil–filled cups were placed all around the store. Many people bought a pencil or two, plucking them out of a cup on impulse, unable to resist the appeal of the memories the yellow No. 2s evoked.

I thought Mirabelle had come into the store to pick up more blue paper but we passed all the paper without stopping, and she was still behind me as we approached the back counter. I sent her an apologetic half smile when we both noticed my niece behind the counter, slunked down in one chair, her feet up on another as she moved with the beat of whatever song played in her earbuds. Her eyes were closed, and she had no idea that either I or a customer was in the building.

I supported the Underwood on my hip and knocked on the top of the counter, startling Marion to opened-eyed surprise. She pulled the buds out of her ears.

“Aunt Clare, Mirabelle, sorry. I didn’t think anyone was in here,” she said as she stood, because standing somehow must have seemed like the right thing to do.

“It’s okay, dear,” Mirabelle said. “Are you listening to one of those rapper singers?”

Marion smiled. “No, ma’am. I was listening to some country music.” She looked at me. “I didn’t know where you were. I walked this morning and saw Mirabelle’s hatchback up but didn’t know you two were behind it.”

“Your Jeep okay?”

“Yeah. Just wanted to walk.”

“We must have crossed paths. Do you know if Chester’s in the workshop?”

“No. I just peeked back there and didn’t see anyone.”

“That’s where I left him,” I said, now curious but not concerned as to where my grandfather had gone. He never did like to stay in one place for very long.

“Maybe he went back upstairs,” Marion said.

My grandfather lived upstairs, in the apartment he’d fashioned when my grandmother died twenty years earlier. When she died, their two children were already gone from the house, so he saw no reason to do much of anything but ski whenever he could and work. He sold the house and the lawnmower and moved to the second floor of his building, taking down walls and adding appliances to make it an open and comfortable space, particularly for a bachelor. Even though I do most of the work now, he claims he still loves living a mere twelve steps away from his store, and a quick walk to the nearest chairlift, of course.

“Maybe,” I said. “Any e-mails?” She had become our stationery personalization pro, doing the work on the computer we kept behind the counter.

“I just got a couple of orders, but nothing urgent.” She nodded toward the monitor.

I looked back toward the front, contemplating which task I wanted Marion to tackle first. As my eyes scanned, something flashed from somewhere, or had I just blinked at the wrong angle and thought I’d seen something? I couldn’t be sure. I squinted and peered out the front windows, all the way to the diner across the street. Had the flash—what might have just been a brief reflection of the sunlight—come from outside, or perhaps the diner? I didn’t see much of anything except indistinct summer-clothes-clad figures either walking down the street or moving around inside the diner. Whatever it had been, neither Marion nor Mirabelle seemed to notice it.

“The middle shelves could use some attention, dusting, arranging,” I said. “And Mirabelle would like some more of her favorite blue paper. Would you gather that for her?”

“Sure,” Marion said with a smile. She was mostly a good kid, but unfortunately she was not only a beautiful young woman with long blond curls and big blue eyes, she was also intelligent and seventeen, and better on a snowboard than almost anyone in town. Talks of her participating in the Olympics had gone from “maybe someday” to “probably the next winter games.” Such a lethal combination created a number of sleepless nights for my brother, a single parent who tried not to be overprotective but failed miserably. I thought he was overcompensating for the fact that Marion’s mother took off shortly after her daughter was born. She had left a note though, saying she was sorry she couldn’t handle the responsibilities of being a mother at the tender age of twenty-one. We didn’t talk about it much.

Everyone said Marion looked just like me, but my seventeen hadn’t been a thing like Marion’s. She’d been able to handle contacts, and her braces had been clear and barely noticeable. The hair products I’d found when I got older were at her disposal by age eleven, when she first started caring about her/our unruly hair. I still couldn’t handle contacts, but I thought I wore my black plastic-framed glasses stylishly enough. Besides Marion’s looks, though, her skills with a snowboard gave her a physical strength and confidence that would have been completely foreign to my teenage self. It was interesting to watch her from this side of those years and see just how much confidence could negate an undesirable trait or two.

“And let’s turn the music off for a while and make this a no-earbud zone,” I said.

Marion tried to stop her look of disappointment before it went too far. “Yes, Aunt Clare. Of course.”

“Thank you.” Mirabelle and I shared a smiled as Marion grabbed a duster from a shelf under the counter.

“You want to come back to the workshop with me?” I asked Mirabelle. It wasn’t a question I asked most people, but Mirabelle had been in the workshop many times over the years. She and my grandfather sometimes shared their coffees back there as they shared stories about the days when snowboards hadn’t existed and manual typewriters were all the rage and pretty much the only writing machines available.

“Sure. I’d actually like to talk to Chester if he’s around,” she said.

I thought I saw a pinch of worry in her eyes but it passed quickly so I didn’t comment.

“Let’s see if we can find him.”

I repositioned the Underwood again and led the way down a short hallway and through a plain door. The back of the building had originally been used by the mining company as one of their small warehouses. Chester had found long-forgotten stuff like pick axes and lighted miner hard hats when he purchased the abandoned building. The apartment on the second floor didn’t extend through this space, so the ceilings back here were the full two-story height, the back wall topped by the same kinds of windows that were in the front of the building, but these faced south, toward the rest of the town, the populated valley that stretched out from the bottom of Main Street. A concrete floor, metal shelves, a couple desks, some work tables, our type case filled with type blocks, other press supplies, and our printing press filled the space, but there was still plenty of elbow room. The shelves were currently topped with typewriters, typewriter parts, tools, press plates, and special paper that we didn’t sell out front but used to restore some of the old books or for customers who hired us for small print runs.

The tall press always made me think of Frankenstein, something big and funny looking, put together well but with parts that didn’t all seem to match, or at least were off sized. With a giant screw mechanism in its middle, its handle protruding outward, and the more sleek press plate extending out like a tongue, I’d long ago given it the name Frank. Chester had gone along and that was what he called it too.

The entire space smelled like books and ink and coffee, appealing and pleasant aromas, even when mixed together. At first glance it probably also looked like one big mess, but it was actually very organized. Most of the time I could find whatever I was looking for—even small tools or spare parts; Chester could find anything at any time.

“Oh! You’re working on a book,” Mirabelle said when she saw that I’d placed a readied plate on the press.

“I am. It’s for a man whose father read to him from this book every night when he was sick for a few months as a child. The book has no financial value at all, but it means the world to the customer.”

“What’s the book?”

“Tom Sawyer. It’s an old edition, but not a first; not even a second. There was just one page missing. I did some research to find the words that go on the page, but that was the easy part. I also had to come up with something that would re-create the design at the top of each page.” I’d set the Underwood on a desk. Mirabelle and I both moved to a spot between Frank and another worktable. “See there?” I pointed to the curlicued pattern on a page of the book. “That was the hard part.”

“Gracious, how did you do it? Did you have it—a stamp or something—made?”

“Nope, I got lucky. I could have had a steel type block made, but it costs quite a bit to have something like that tooled. The customer would have paid but I hoped to avoid that if possible. Chester has connections all over the world—people who collect stuff like these blocks. I found this exact one from a gentleman who lives in Romania. He’s letting us borrow it.”

Mirabelle shook her head slowly. “All for one silly little page in a book?”

I smiled. “Yep, one silly little page.”

“That’s amazing.”

I didn’t counter with how much fun it was. But it was fun to restore a book, whether one page or more, whether printing or rebinding or just cleaning it up a bit. It was also fun to bring an old typewriter back to life: make the keys work again, the bell ding properly, the carriage return smoothly. I’d found my career by accident, by hanging out with my grandfather and Arial when I was a kid. Chester had patiently taught me everything he knew about rescuing all sorts of words, bringing them back to life, perhaps even making them better than they were before.

Mirabelle was about to ask another question when a crash interrupted our conversation. The noise seemed to come from the space at the corner of the workshop, the area where my computer office was hidden behind another door. The staircase that led up to the apartment was on the other side of my office and also hidden from where we stood. I was afraid Chester had fallen down the stairs.

I stepped around the press and the worktable just as a voice called.

“Clare! Get over here and help me, young lady!”

“Chester?” I said as I hurried.

I skidded to a halt once I turned the corner and faced both the stairs and the office. The good news was that Chester wasn’t in a heap at the bottom of the steep steps.

But the news wasn’t so good in my office. I wasn’t sure exactly what had happened, but there was most definitely a heap of my stuff on the office floor, and my grandfather sat clumsily atop it.

2

“Chester, what happened?” I asked as I helped him stand.

“Oh, I got caught,” he said.

Chester Henry was not delicate. Never had been, never would be if he had his way. He was seventy-seven years old but moved like someone much younger. He carried his six-foot frame confidently, his spine straight, with wide shoulders that were still not bony with age. He had a head full of thick white hair with a sizeable, perfectly groomed mustache to match. His skin was pleasantly wrinkled and probably permanently tanned with goggle outlines from years of exposure to the winter sun. From the age of about twelve, he’d also worn glasses. Since the moment he’d first donned them, he’d chosen round, gold wire frames. He’d met my grandmother not long after he’d first acquired the glasses, at the age of thirteen, and she told him that the round shape and the gold color made his blue eyes so “very lovely to look at.” That sealed the deal and he’d never worn any other types of frames.

When not in ski clothing, his typical outfit of choice was a nice pair of pants, a button-up long-sleeved shirt with the sleeves always rolled up, and a sweater-vest, even in the summer. The only change that I ever remembered noticing was when he switched from wearing dress shoes to tennis shoes because they were so much more comfortable. That switch had come when I was probably six or seven.

Though neither physically nor mentally fragile, he did have an Achilles heel that kept him highly deficient in one particular area: technology. For some reason, he’d never quite understood cell phones, and computers had seemed hypocritical for someone “who fixed manual typewriters, for goodness’ sake!” But I’d been pushing him to take the one-page, merely informational website that I’d created for The Rescued Word and expand it, hire someone to create a real online presence, something with a retail facet that would enable us to sell paper and pens to customers visiting us through the World Wide Web. He’d been fighting any such advancement, but we’d managed to get as far as letting customers know that we had a personalized stationery designer in house. One line had been added to our page: “Personalized Stationery Questions? E-mail Marion” and then her e-mail address. Her contribution to the business was growing steadily, but there was more we could do, more we could say to the world about our wonderful little shop nestled in our beautiful Utah mountain town. I’d tried and tried to show him other sites, how shopping carts worked, how easy it would ultimately be to oomph things up. And, though he hadn’t bought on, I’d caught him a couple of times in my office, grimacing at the computer screen and moving the mouse. He’d never fess up to what he was really doing: trying to understand the universe inside that dangburnit box, but I knew.

“You got caught?”

“Yes. That wire was somehow wrapped around my elbow. When I went to stand up, I pulled it along the desk and it pulled everything down, me included. See, what I have told you about all this stuff?”

I inspected the “wire” and tried to visualize what had happened. It seemed that the cord from my mouse had somehow become wrapped around Chester, and when he went to stand, he pulled the keyboard and a stack of books that had been sitting on the corner of the desk onto the floor. And then he himself went to the top of the small pile. Just yesterday I’d been thinking about buying a wireless mouse. I guess I needed to get my own technology in gear.

“Are you hurt?” I asked.

“Of course not,” he said as he straightened the bottom of his red sweater-vest and adjusted his glasses. “I was just afraid to stand up without you here in case I was still tied to that contraption. Who knows what I might have broken.”

I nodded and smiled. “I understand. What were you doing?”

“Just fiddling around. Taking some time to figure out that crazy computer. See, the fates are against me, Clare, so very heavily armed against me. Every time I try to understand more, I end up understanding less, or creating a mess.”

“It’s not a big mess. Here, we can get it cleaned up quickly,” I said as I made a move to reach toward the items on the floor.

“Hello there, Mirabelle,” Chester said as he took a long-legged step over the pile of books and keyboard. “How wonderful to see you. Has Clare offered you coffee yet?”

The two of them left the vicinity of my office, evidently trusting me to handle the cleanup alone. I was sure they immediately ventured toward the coffee machine and the small table and chairs set at the other corner of the workshop.

Chester was typically pretty conscientious about cleaning up after himself. His hasty exodus was somewhat strange, but maybe he thought it would be rude to Mirabelle to pick up a few books before joining her. Maybe he was simply embarrassed and rattled. I didn’t mind straightening things, but it was all just unusual enough that I became more curious about the entire scene, about what he’d been doing.

After I picked up the books—thankfully, none of them valuable or belonging to customers—and placed them and the undamaged keyboard and mouse back in their respective spots, I sat in the chair and pushed the button on the monitor. If he’d been on th

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...