- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

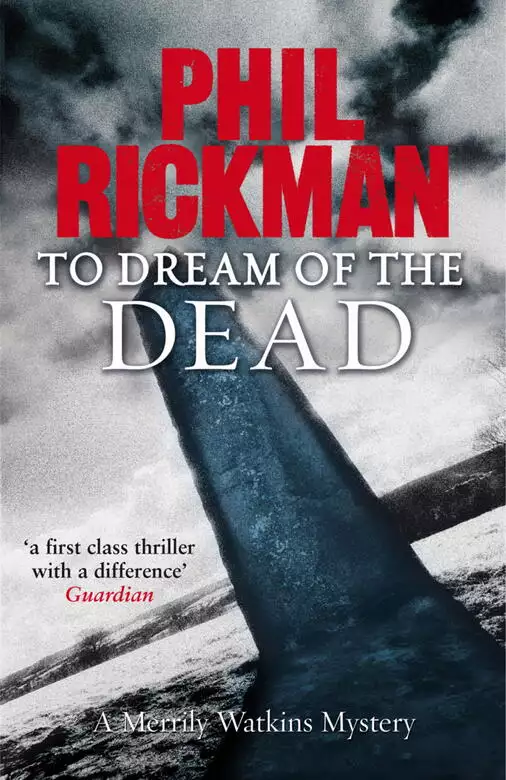

Synopsis

Late December and the river is rising. The Herefordshire village of Ledwardine has not been flooded in living memory but in these days of climate change nothing is certain. Merrily Watkins, parish priest and diocesan exorcist, has learned that one of the incomers is an author who is a figure of hate for religious fundamentalists. Meanwhile, the Hereford police make a gruesome discovery linked to the Dinedor Serpent, a unique prehistoric monument. In Ledwardine itself, buried Bronze Age stones have been unearthed. Overnight, the village is isolated in the floods, cut off with a killer inside. As the waters rise, shocking savagery paralyses an ancient community untangling its own history against the swirling uncertainty of the future.

Release date: December 22, 2011

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 528

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

To Dream of the Dead

Phil Rickman

High Town on a damp midwinter evening, fogged faces around the fast-food outlets. Bliss was waving cheerfully to his kids on the painted horses. Doing the dad thing. His kids not exactly waving back, just minimally hingeing their fingers, sarcastic little sods.

Kirsty’s kids. Hereford kids, somehow fathered by Francis Bliss from Knowsley, Merseyside. His kids had Hereford accents. His kids’ little mates thought he talked weird, laughing at him behind their hands, trying to imitate him, this joke Scouser.

Joke Scouser in Hereford. On two or three Wednesday evenings before Christmas – a tradition now in the city – shops would open until nine p.m. Bliss and Kirsty and the kids had been three years running; must be a tradition for them, too.

So why were the festive lights ice-blue? Why no carol singers, no buskers, no exotic folkies in hairy blankets playing ‘Silent Night’ on the Andean pipes?

Maybe the council’s Ethnic Advisory Directorate had advised against, in deference to Hereford’s handful of Muslims.

‘They’re coming round again,’ Kirsty said. ‘Wave.’

Bliss waved at the carousel. It was like a birthday cake at a frigging funeral tea. Beyond it, too many shopfronts dulled by low-powered security lighting. Car-friendly superstores coining it on the perimeter while the old town-centre family firms starved to death. Now the council was creating this massive new retail mall on the northern fringe, swallowing the old cattle market, answering no obvious need except to turn Old Hereford into something indistinguishable from the rest of the shit cities in landfill Britain.

Watching the random seepage of shoppers – going nowhere, buying not much – Bliss felt lonely. Kirsty had moved away from the carousel, gloved hands turning up the collar of her new sheepskin jacket.

‘All right, Frank, what’s the matter with you?’

He sighed, never able to tell her just how much he hated that. Growing up, it was always Frannie, Francis on Sundays, but Kirsty had to call him Frank.

‘I don’t understand you any more,’ Kirsty said. ‘One night for me and the children. Just one night . . .’

‘For the children?’ Bliss staring at his wife. ‘Kairsty, they’re only doing it for our sake. They’d rather be at home, plugged into their frigging computers.’

‘Yes,’ Kirsty said grimly. ‘You would say that, wouldn’t you?’

‘Don’t think it gives me any pleasure.’

‘What does give you pleasure, Frank?’

Kirsty turning away – not an answer she could face. Bliss breathing in hard and shutting his eyes, the carousel crooning through its speakers about letting it snow, when it so obviously wasn’t going to snow, not tonight and definitely not for Christmas; what it was going to do was rain and rain, and nobody ever sang let it frigging rain.

Bliss spun round instinctively at the sound of a ricocheting tin.

Lager can. It rolled out in front of the Ann Summers store, which seemed to be closed. It had bounced off a bloke wearing an ape suit and an ape mask and a sandwich board pleading DON’T LET DRINK MAKE A MONKEY OUT OF YOU.

Three young lads, early teens, were jetting fizzy beer at the feller in the ape suit. Two community support officers moseying over, a young woman and a stocky man with a delta of cheek veins.

‘Fuck me,’ one of the kids said. ‘Who sent for the traffic warden?’

‘. . . your language, boy.’ The senior plastic plod visibly clenching up – you had to feel sorry for them. ‘How old are you?’

The boy went right up to him, thin head on an exaggerated tilt, teeth like a shark’s, embryo of a moustache.

‘And how old are you, grandad?’

‘You throw that tin?’

‘What you gonner do, run me over with your Zimmer, is it?’

Bliss purred like a cat, deep in his throat, Kirsty muttering, ‘You’re off duty, Frank.’

The three kids had formed a rough semicircle now, in front of a blacked-out shopfront with a poster on the door: SAVE THE SERPENT.

‘You can’t arrest us,’ another of them said to the support guy. ‘You got no powers of arrest. You can’t fucking touch us, ole man, you’re just—’

‘However . . .’ In this crazy blaze of . . . well, it might not be actual pleasure but it was certainly relief, Bliss had found himself at the centre of the action ‘. . . I can.’

As if he was frigging Spiderman just landed from the roof. Or a magician, his ID appearing like the ace of spades in his left hand. He could hear Kirsty backing off, heels clacking like a skidding horse.

‘What’s more . . .’ Committed now, Bliss advanced on the biggest kid, the old accent kicking in like nicotine ‘. . . I also happen to have a key to the notoriously vomit-stained cell we fascist cops like to call Santa’s Grotto.’

Bliss smiling fondly at the kid, and the kid sneering but saying nothing.

‘Fancy a few hours in the Grotto, do we, sonny? Sniffing icky sicky, while we wait for our old fellers to drag their arses out the pub and come and fetch us? Or maybe they won’t bother till morning. I wouldn’t.’

A movement then, from one of the others in the shadow of a darkened doorway – hand dipping into a pocket down his leg. Knife?

Jesus . . . careful.

Kids. Frigging little scallies. Grown men were easier these days, these three too young and maybe too pissed to understand that sticking a cop bought you zero sanctuary.

Difficult. Bliss didn’t move, snatching a quick glance at the plastic plod who’d got his arms spread like a goalie, which meant that if knifeboy went for him now the old feller would catch it full in the chest. Mother of God, who trained these buggers?

The hand came out of the pocket, the fear-switch in Bliss’s trip-box giving a little tremble. Best to stay friendly.

‘Up to you, son. B-and-B in the grotto, is it?’

Boy’s hand still in shadow. Instant of crackling tension. Wafting stench of hot meat from a fast-food van.

Nah. Empty.

Pretty sure. Most likely the pocket was empty, too. This was still Hereford. Just. Feed him a get-out.

‘Yeh, thought not. Now piss off home, yer gobby little twats.’

Watching them go, one looking back, about to raise a finger, and Bliss taking a step towards him—

‘You do that again, sunshine, and I will frigging burst you!’

—as the mobile started shuddering silently in his hip pocket and the carousel invited them all to have a merry little Christmas.

‘Good of you, sir,’ the community-support woman said. ‘It’s, um, DI Bliss, isn’t it?’

‘No way,’ Bliss said. ‘Not here, luv. Got enough paperwork on me desk.’

Realising he was sweating, and it wasn’t warm sweat. This sharpend stuff . . . strictly for the baby bobbies and the rugby boys. Ten years out of uniform, you wondered how anybody over twenty-five could keep this up, night after night.

He dragged out his still-quivering phone, flipped it open, feeling not that bad now, all the same, and not considering the possible consequences until he looked up and saw those familiar female features gargoyling in the swirl of light from the carousel and remembered that he wasn’t here on his own.

‘You bastard.’

Gloved hands curling into claws.

‘Kirsty, tell me what else I—’

‘You swore to me you’d left that bloody thing at home.’

Bliss squeezed the phone tight.

‘Never gonner change, are you, Frank?’

Kirsty’s face glowing white-gold as the little screen printed out KAREN. Bliss slammed the phone to an ear.

‘Karen.’

‘Thought you’d want to know about this, boss. Where exactly are you?’

‘Pricing vibrators in Ann Summers.’ Bliss was feeling totally manic now. ‘Complete waste of money nowadays, Karen, what’s a mobile for? Pop it in, get yer boyfriend to give you a ring. Magic.’

Stepping blindly into the extreme danger zone; no way he could share that one with Kirsty.

Like, indirectly, he just had.

‘You could be there in a few minutes, then,’ Karen said.

Bliss looked up at the clock on the market hall. Eight minutes to nine.

‘You shit, Frank!’

‘Kirst—’

‘You stupid, thoughtless, irresponsible piece of shit! Suppose one of them youths’d had a knife? Or even a gun, for Christ’s sake? What about your children?’

‘Jesus, Kirsty, it’s not frigging Birmingham!’

Kirsty spinning away in blind fury, Karen saying, ‘Um, if you’ve got a domestic issue there, boss, I can probably reach Superintendent Howe—’

‘Acting Superintendent.’ Bliss saw the carousel stopping, his kids getting down. ‘Let’s not make it any worse. What is this, exactly? Go on, tell me.’

‘It’s a murder, boss.’

‘We’re sure about that, are we?’

‘You know the Blackfriars Monastery? Widemarsh Street?’

‘That’s the bit of a ruin behind the old wassname—?’

‘Coningsby Hospital. Look, really, if there’s a problem . . .’

‘No problem, Karen.’

Bliss pulled out his car keys, shrugged in a sorry, out-of-my-hands kind of way, and held them out to Kirsty. It was like pushing a ham sandwich into the cage of the lioness with cubs, but they’d need transport.

‘Five minutes, then, Karen. You’re there now?’

‘Yeah.’

‘You all right, Karen?’

Something in her voice he hadn’t heard before. Other people’s, yes, coppers’ even, but not hers.

‘Yeah, it’s just . . . I mean, you think you’ve seen it all, don’t you?’

‘Doc ’n’ soc on the way?’

‘Sure.’

‘Don’t bother coming home tonight, Frank.’ Kirsty ripping the bunch of keys from Bliss’s fingers, the two kids looking pitiful. ‘You can go home with Karen. Spend the other five per cent of your time with the bitch.’

Bliss covered the bottom of the phone, the plastics looking on; how embarrassing was this?

Karen said, ‘Before somebody else tells you, boss, I’ve contaminated the crime scene. Threw up. Only a bit. I’m sorry.’

‘It happens, Karen.’

Not to her, though. Bliss was remembering how once, end of a long, long night, he’d watched Karen Dowell eat a whole bag of chips in the mortuary. With a kebab? Yeh, it was a kebab.

Kirsty was walking away, holding Naomi’s hand in one of hers, Naomi holding one of Daniel’s. Of course, the kids were both a bit too old for that; Kirsty was blatantly making a point, the kids playing along, the way kids did.

It was six days from Christmas.

And yeh, he felt like a complete shit.

But not really lonely any more. What could that mean?

‘So don’t say I never warned you, Frannie,’ Karen Dowell said.

COMING UP TO seven p.m., it stopped raining and Jane went to get some sense out of the river.

Slopping in her red wellies across the square, where the electric gaslamps were pooled in mist, and down to the bottom of Church Street, glossy and slippery. On the bridge, she looked over the peeling parapet, watching him licking his lips.

‘You’re not actually going to do this . . .?’

Zipping up her parka to seal in a serious shiver, because she didn’t recognise him any more. In this county, the Wye was always the big hitter, lesser rivers staying out of the action. In old pictures of the village, this one was barely visible, a bit-player not often even named. Slow and sullen, this guy, and – yeah – probably resentful.

Tonight, though, for the first time Jane could remember, he was roaring and spitting and slavering at his banks. All those centuries of low-level brooding, and then . . . hey, climate change, now who’s a loser?

‘Only, I thought we had an understanding,’ Jane said, desolate.

Because if this guy came out, there was no way the dig would start before Christmas.

Wasn’t fair. All the times she’d leaned over here, talking to him – influenced, naturally, by Nick Drake’s mysterious song, where the singer goes to tell the riverman all he can about some kind of plan. Nobody would ever know what the plan was because, within a short time, Nick Drake was dead from an overdose of antidepressants, long years before Jane was born, with only Lol left to carry his lamp.

Above a flank of Cole Hill, the moon was floating in a pale lagoon inside a reef of rain clouds. Jane’s hands and face felt cold. She looked away, up towards the haloed village centre and the grey finger of the church steeple. She’d seen the news pictures of Tewkesbury and Upton: canoes on the lanes, homes evacuated. It had never happened here to that extent, never – people kept insisting that.

But these were, like, strange days.

The main roads around Letton – always the first place north of Hereford to go – had been closed just after lunch, due to flash floods, and the school buses had been sent for early. Nobody wanted to spend a night in the school, least of all the teaching staff, and there was nothing lost, anyway, in the last week before Christmas.

Fitting each hand inside the opposite cuff, Jane hugged her arms together, leaning over the stonework, sensing the extreme violence down there, everything swollen and turbulent.

Across the bridge, a puddle the size of a duck pond had appeared in the village-hall car park, reflecting strips of flickering mauve light from the low-energy tubes inside. The lights were on for tonight’s public meeting – which wasn’t going to be as well attended as it ought to be. It had somehow coincided with late-night Christmas shopping in Hereford. No accident, Mum thought, and she was probably right. A devious bastard, Councillor Pierce.

‘Janey?’

Lamplight came zigzagging up the bank, bouncing off familiar bottle glasses, and Jane dredged up a grin.

‘You been snorkelling or something, Gomer?’

Up he came from the riverside footpath, over the broken-down wooden stile, the old lambing-light swinging from a hand in a sawn-off mitten. Patting at his chest for his ciggy tin. Still quite nimble for his age, which was reassuring.

‘What do you reckon, then?’ Jane said. ‘Seriously.’

‘Oh, he’ll be out, Janey, sure to.’

‘Really?’

‘Count on him.’

‘When?’

‘Tonight, mabbe tomorrow.’

Gomer set the lamp on the wall, its beam pointing down at the water.

His specs were speckled with spray and his white hair looked like broken glass.

‘You mean if it rains again?’ Jane said.

‘No ifs about it, girl.’ Gomer mouthed a roll-up. ‘Ole moon sat up in his chair, see?’

‘Chair?’

Jane peered at him. This was a new one. Gomer brought out his matches.

‘Ole moon’s on his back, he’ll collect the water. Moon’s sat up, it d’ run off him, see, and down on us. You never yeard that?’

‘Erm . . . no.’

‘Yeard it first from my ole mam, sixty year ago, sure t’ be. Weather don’t change, see.’

‘It does, Gomer.’

She must’ve sounded unusually sober against the snarling of the water because he tilted his head under the flat cap, peering at her.

‘Global warmin’? Load of ole wallop, Janey. Anythin’ to put the wind up ordinary folk.’

‘You seen those pictures of the big ice-cliffs cracking up in the Antarctic?’

Gomer’s match went out and he struck another.

‘All I’m sayin’, girl, science, he en’t got all the answers, do he?’

‘Yeah, but something has to be going on, because this hasn’t happened before, has it?’ Jane feeling her voice going shrill; it wasn’t a joke any more – up in the Midlands people had died. ‘I mean, have you seen this before? Like, here? We ever come this close to a real flood?’

‘Not in my time, ’cept for the lanes getting blocked, but what’s that in the life of a river?’ Gomer looked up towards the square, where the Christmas tree was lit up like a shaky beacon of hope. ‘You’ll be all right, Janey. En’t gonner reach the ole vicarage in a good while.’

‘What about your bungalow?’

She didn’t think Gomer’s bungalow was on the flood plain, but it had to be close. Always said it wasn’t where he’d’ve chosen to live but Minnie had liked the views.

Gomer said he’d brought one of his diggers down. Took real deep water to stop a JCB getting through.

‘En’t sure about them poor buggers on the hestate, mind.’

Nodding across the bridge at the new houses, one defiantly done out with flashing festive bling – Santa’s sleigh, orange and white, in perpetual, rippling motion. The estate had been built a couple of years ago, and most of it was definitely on the flood plain – which, of course, nobody could remember ever being actually flooded, although that wouldn’t matter a toss anyway, when the council needed to sanction more houses. Government targets to meet, boxes to tick.

This was possibly the most terrifying thing about growing up: you could no longer rely on adults in authority operating from any foundation of common sense. They just played it for short-term gain, lining their nests and covering their backs. How long, if Gomer was right, before the Christmas Bling house became like some kind of garish riverboat?

‘What about Coleman’s Meadow, Gomer? If the river comes out, could the flood water get that far?’

Twice they’d abandoned the dig – Jane really losing hope, now, that anything significant would be uncovered before the end of the school holidays, never mind the start.

‘Could it, Gomer?’

‘You still plannin’ to be a harchaeologist, Janey?’

‘Absolutely. Two university interviews in the New Year. Fingers crossed.’

Be fantastic if she could someday work around here. The Ledwardine stones could all be in place again by the summer, but there were probably years of excavation to come on the Dinedor Serpent, the other side of Hereford, and who knew what else was waiting to be found? Suddenly, this county had become a hot spot for prehistoric archaeology – two really major discoveries within a year. As though the landscape itself was throwing off centuries like superfluous bedclothes, an old light pulsing to the surface, and Jane could feel the urgency of it in her spine.

‘Gomer, is the meadow likely to get flooded?’

‘Mabbe.’ Gomer took out his ciggy, fingers sprouting from the woollen mittens. ‘Lowish ground, ennit?’

‘The thing is, if they think it could ruin the excavation, they might not even start it till there’s no danger of it all getting drowned.’

Meanwhile, Councillor sodding Pierce, who didn’t give a toss what lay under Coleman’s Meadow, would keep on trying to screw it, like his council had done with the Serpent. Playing for time, and Jane would be back at school before they got to sink the first trowel.

‘You going to the parish meeting, Gomer?’

‘Mabbe look in, mabbe not. Nobody gonner listen to an ole gravedigger. You still banned, is it, Janey?’

‘Well, not banned exactly. Mum’s just . . .’

. . . politely requested that she stay away.

It’s not going to help, flower. It’s reached the stage where we need a degree of subtlety, or they’re going to win.

Mum thinking the mad kid wouldn’t be able to hold back, would make a scene, heckling Pierce, making the good guys look like loonies.

The brown water flung itself at the old sandstone bridge, and Jane, officially adult now and able to vote against the bastard, bit her lip and felt helpless. Even the riverman was on the point of betraying her.

‘Dreamed about my Min last night,’ Gomer said.

Jane looked at him. His ciggy drooped and his glasses were as grey as stone.

‘Dreamed her was still alive. Us sittin’ together, by the light o’ the fire. Pot of tea on the hob.’

‘But you—’

‘En’t got no hob n’ more. True enough. That was how I knowed it was a dream.’ Gomer steadied his roll-up. ‘Was a good dream, mind. En’t often you gets a good dream, is it?’

Nearly a couple of years now since Minnie’s death. Close to the actual anniversary. Gomer had put new batteries in both their watches and buried them in the churchyard with Minnie. Maybe – Jane shivered lightly – one of the watches had finally stopped and something inside him had felt that sudden empty stillness, the final parting.

‘You know what they says, Janey.’

‘Who?’

‘Sign of rain,’ Gomer said.

‘Sorry?’

‘What they used to say. My ole mam and her sisters. To dream of the dead . . .’

‘What?’

‘To dream of the dead is a sign of rain.’

‘That’s . . .’ She stared hard at him. ‘What kind of sense does that make?’

‘Don’t gotter make no partic’lar sense,’ Gomer said. ‘Not direc’ly, like, do it?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘These ole sayings, they comes at the truth sideways, kind of thing.’

‘Right,’ Jane said.

It seemed to have gone darker. The clouds had closed down the moon, and the village lights shone brighter as if in a kind of panic. New rain slanted into Jane’s cheeks, sudden, sharp and arrogant, and she thought about her own troubled nights, worrying about the dig, the future, her own future, Eirion . . .

‘So, like, what’s supposed to happen,’ she said, ‘if you dream about the rain?’

ONE OF HEREFORD’S little secrets, this ruin. In daylight, at the bottom of a secret garden surrounded by depots, offices and a school, you could easily miss it; most people, tourists and locals, didn’t even know it existed.

But with night screening the surroundings, Bliss thought, it was a sawn-off Castle Dracula.

‘So where is it?’

Looking around in case he’d been scammed; wouldn’t be the first time these bastards had done it to him, especially around Christmas, but he wouldn’t have expected it of Karen Dowell.

‘The body, Karen?’

Bending his head on the edge of the blurry lamplight to peer into her fresh, farmer’s-wife face.

‘The body . . . we don’t exactly know, boss,’ Karen said.

‘What?’

Had to be eight of them in the rose garden in front of the monastery. Bliss had registered DC Terry Stagg, several uniforms and two techies, clammy ghosts in their Durex suits.

On balance, too many for a scam. And there was this little trickle of unholy excitement, which would often accompany shared knowledge of something exquisitely repellent.

Bliss looked around, recalling being here once before. One of the kids had been involved in some choir thing at the Coningsby Hospital which fronted the site on lower Widemarsh Street. Coningsby was only a hospital in some old-time sense of the word, more of a medieval chapel with almshouses and an alleyway leading to the rose garden, where there was also a stone cross set into a little tower with steps up to it.

‘’Scuse, please, Francis. Let the dog see the rabbit.’

Crime-scene veteran Slim Fiddler, seventeen stone plus, squelching across the grass, messing with his Nikon. A strong wire-mesh fence separated the ruins from the St Thomas Cantilupe primary school next door. Slim Fiddler stopped a bit short of it, turned round, and the other techie, Joanna Priddy, moved aside as his flash went off.

Which was when Bliss also saw, momentarily, the rabbit.

Saw why Karen had chucked her supper.

The body . . . we don’t exactly know, boss.

The cross . . . its base seemed to be hexagonal. About four steps went up to the next tier, which was like a squat church tower with Gothic window holes, stone balcony rails above them, and the actual cross sprouting from a spire rising out of the centre.

Thought it was a gargoyle, at first. When the flash faded, it had this stone look, the channels of blood like black mould.

‘Fuck me,’ Bliss said quietly.

The face was looking out from one of the Gothic windows.

‘If you’re going up there, best to get kitted up, Mr Bliss.’

Joanna Priddy handed him a Durex suit and Bliss clutched it numbly, as the rain blew in from Wales.

‘Who found it?’

‘Bloke came in for a smoke,’ Karen said. ‘Nobody knows where it’s legal to light up, any more, do they?’

‘Like we’re supposed to care.’

‘Comes round the back of the cross to get out of the wind, flicks his lighter and . . .’

‘Swallows his cig?’ Bliss said. ‘We looking at gangland here, Karen, or what?’

‘I’d like to think we could rule out a domestic, boss.’

Bliss thought for a moment about two baddish faces he’d eyeballed walking over from High Town. After dark, away from the city centre, the people you passed became predominantly male and increasingly iffy. The whole atmosphere of this Division had changed a good deal in the past few years.

‘Just the head, Karen? No other bits?’

‘Not that we’ve found. There’s a brick behind it, stood on end to prop it up. And a piece of tinsel – you can’t see it now from the ground. It was round the neck, but it’s slipped down.’

‘Like people put round the turkey on the dish?’

‘Probably.’

‘Very festive,’ Bliss said. ‘I presume someone’s checked it’s, you know, real?’

‘Why do you think I threw up? Not much, mind, but it was the shock, you know? Not like anything I’ve . . .’

Bliss nodded. In no great hurry, frankly, to put on the Durex suit and take a closer look. He clapped his hands together.

‘Right, then. Let us summon foot soldiers. If the rest of this feller’s bits are anywhere in the vicinity, I want them found before morning. I want this whole compound sealed and that school closed tomorrow. Where’s Billy Grace?’

‘Might not actually be Dr Grace,’ Karen said. ‘Somebody’s on the way.’

‘This cross – it’s got a name?’

‘I’m not sure, boss. There’s some kind of information board at the back.’

Karen led Bliss towards the wire fence, the school building on the other side. She held up a torch; Bliss scanned the sign.

Built in the 14th century and considerablyrestored in the 19th century, this is the onlysurviving example in the county of a preachingcross . . .. . . built in conjunction with the BlackfriarsMonastery . . .. . . given the order by Sir John Daniel . . .. . . beheaded for interference in baronialwars in the reign of Edward III

‘And when they’d topped him, did they by any chance display this Sir John’s head on his own cross?’

‘I wouldn’t know, boss.’

‘I mean, it’s not some old Hereford tradition?’

‘Not in my time,’ Karen said.

‘Somebody’s looking for maximum impact here, Karen. Kind of Look what I’ve done.’

‘Maybe more impact than you actually . . . Here.’ Karen handing him the rubber-covered torch. ‘Might not’ve shown up with the flash. Try that. From where you are.’

Bliss switched on the flashlight, tracked the beam up from the base of the cross. The light finding what remained of the neck, black blood, gristle.

‘Boss . . .’

‘What?’

‘Back off. Move the light up a bit.’

Karen came alongside him and lifted his arm slightly, steadying it when the beam found the . . .

‘Bugger me,’ Bliss said.

‘Yeah, if you back right off it’s all you can see at first.’

Bliss switched off the torch, took a few steps back, snapped it on again.

‘What’ve they done? It’s like it’s . . .’

‘Still alive,’ Karen said. ‘Sorry about the smell of sick.’

‘You’re excused,’ Bliss said.

The black hole behind the spinning lights.

How black did you want?

IT WAS A question of which century you wanted to live in, sleek, thirtyish Lyndon Pierce was telling them. Which millennium, even.

‘Comes down to that, people. All comes down to that.’

Punching the table. People? Pierce had been watching American politicians on TV?

There was silence.

Pierce stopped talking and Merrily noticed the way he patted his gelled black hair, his eyes swivelling around the 1960s pink-brick community hall, as if suddenly unsure of his ground. She leaned over, whispering in Lol’s ear.

‘Misjudged his audience, do you think?’

‘Maybe not quite the audience he was expecting,’ Lol said. ‘Fixing it to coincide with shopping night in Hereford . . . bad move? Your night shoppers are the local working people. He’s just realising what he’s got here are mainly white settlers.’

‘Mmm.’

Merrily guessing that the house lights would come up at the end of the meeting on too many faces she wasn’t going to recognise. At one time, as parish priest, you’d try to connect with all the newcomers. But turning up on doorsteps in a dog collar these days would cause a few to feel pressurised, patronised or – worst of all – evangelised. The incomers from Off, this was. The ones who were not Lyndon Pierce’s people. The ones who really wanted to be living at least a century ago, as long they didn’t have to go to church.

Almost a majority now in Ledwardine, the weekenders and the white settlers. Many of them coming here to retire, but that didn’t mean what it used to – business people were quitting at forty-five, flogging the London terraced for a million-plus and downsizing to a farmhouse with four acres and outbuildings you could turn into holiday cottages. County Councillor Pierce pressed his palms into the table, leaning forward.

‘Even when I was a boy, look, this was a very different place. Rundown, bad roads, no facilities. Not exactly sawdust on the floor of the Black Swan, but you get the idea.’ He straightened up, shaking his gleaming head. ‘Drunkenness? Violence? Goodness me, people, they talk about binge drinking nowadays, but my grandfather could tell you stories would make your hair curl. Stories of hard times, brutal times. Low pay, poverty, disease . . .’

Pierce was still shaking his head sadly, Lol shaking his in incredulity, leaning into Merrily.

‘He’s talking bollocks, right? Just tell me he?

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...