- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

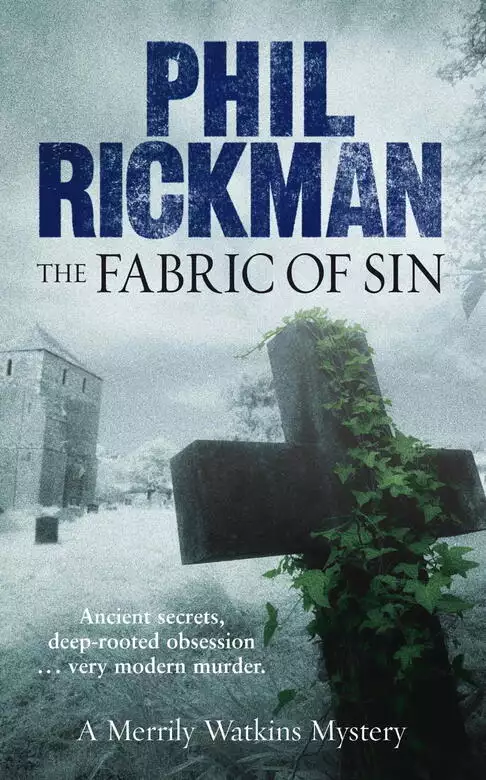

Garway church was built by medieval Knights Templar, and after seven centuries, the Welsh Border village is still shadowed by their mysteries. A few fields away, the Master House, abandoned and falling into ruin, has been sold to the Duchy of Cornawll. But renovation plans stall when a specialist builder refuses to work there, insisting it’s a place that doesn’t want to be restored. Directed by the Bishop of Hereford to investigate, Merrily Watkins is wary of being used and suspicious of the people she’s supposed to be helping. But violent death changes everything, and Merrily uncovers hidden layers of sin and retribution in a secretive landscape.

Release date: September 6, 2007

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 543

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Fabric of Sin

Phil Rickman

Standing at the barn window with Adam Eastgate, she tracked them, right to left, from the southern end of the Black Mountains: the volcanic-looking Sugar Loaf and the ruined profile of The Skirrid which legend said had cracked open when Jesus Christ died on the cross.

Still somehow sacred, these hills. No towns crowded them, nobody messed with them.

At least, not the way someone had with the third and lowest hill, the only one this side of the Welsh border but still maybe a dozen miles away. The third hill had been stabbed under its summit, some kind of radio mast sticking out like a spear from the spine of a fallen warrior, a torn and bloody pennant of cloud flurrying horizontally from its shaft.

‘Oh,’ Merrily said, realizing. ‘Right. They say it’s like another country up there.’

Garway.

The light through the window was this deep, fruity pink, the sun dying somewhere behind the hill with its radio mast, its famously enigmatic church and a farmhouse called the Master House that they were saying was haunted.

Adam Eastgate had been aiming a forefinger like he wanted to stab the hill himself, again and again. Sighing, he let his hand fall.

‘We don’t often make mistakes, Merrily.’

She’d never actually been to Garway Hill. Nor, before today, to this place either – a tidy cluster of converted farm buildings off a dead-end country lane, maybe three miles outside the city. Pieces of Herefordshire adding up to more than twelve thousand acres were administered from here, on behalf of perhaps the most prestigious landlord in the country, and she hadn’t even heard of it.

All the stuff you ought to know about and didn’t. Sometimes this county could be just a little too discreet. All a bit awkward. Merrily turned away from the window and the hills.

‘Jane and I – my daughter – we keep planning to go over to Garway, check out the Knights Templar church. Somehow never seem to find the time.’

‘Aye, we saw it with the Man, when he came to inspect the farm. Likes a quiet stroll when he can. And, of course, it’s always so quiet there, nobody noticed us even when—’ Adam Eastgate slipping her a cautious glance. ‘Why are you smiling?’

‘You might not have seen a soul, but it’d be all over the hill before he was back in his Land Rover.’ Merrily looked down at the outline plans on the conference table. They were blurred. She rubbed her eyes. ‘He inspects every property you take on? Personally?’

‘Aw, hey, he’s not just a figurehead.’

The brackeny accent digging in – Northumbria. In his dry, soldierly way, Adam Eastgate was affronted. Very protective of the Man, the people working here.

‘Does he know about this particular problem then?’

Eastgate didn’t reply, which could have meant yes or no or not something you’re supposed to ask.

‘OK, then.’ Merrily sat down in one of the high-backed chairs, red brocade. ‘What, specifically, are we looking at?’

‘Oh hell, I can’t tell you. Perhaps I wasn’t listening hard enough, y’know?’

‘Or you find it embarrassing?’

‘Not a question of embarrassment, Merrily, I’m just not the man it happened to. If anything did.’

Always the get-out clause.

‘How would you like me to play it, then?’

‘How would you normally play it?’

‘Well …’ Dear God, how long was this going to take? ‘To begin with, we usually try to find out if there’s a back-story. Talk to local people, village historian – there’s always a village historian. Or maybe—’ She clocked his wince. ‘That would be the wrong approach, would it?’

‘Depends if you want it on American TV before the week’s out.’

‘Seriously?’

‘Merrily …’ Tight smile. ‘I’m the land-steward. Deal with builders, architects … and tenants, right? Most of whom … good as gold. But we know if we’re forced to evict somebody who hasn’t parted with the rent for two years, next day’s tabloids we’re half-expecting Prince Puts Family on the Street.’

‘Oh.’

‘You see where we’re going?’

‘Haunted Prince calls in Exorcist?’

Eastgate shuddered. Nice chap, Adam, the Bishop had said. Knows what he wants and how to get it done. But raising this had taken the best part of half an hour and three false starts.

This had been two nights ago, one of those receptions where the Duchy was explaining its ambitious conservation plans to the great and the good of Hereford. The Bishop and the Archdeacon and their wives were having a drink afterwards with Adam Eastgate when the Garway investment had come up. And its complications. You could imagine the Bishop nodding helpfully. We do have a person, you know, looks after this kind of thing.

‘I mean, you’ll’ve read the stuff, same as I have,’ Eastgate said. ‘He only has to venture an off-the-cuff opinion on whatever it is – architecture, alternative medicine, GM foods …’

‘The benefits of talking to plants?’

‘See, there you go! That’s exactly it. How many years ago was that? But do they ever forget?’

Well, no. This was the nation’s last bit of official glitter, a face from commemorative investiture plaques, Royal Wedding mugs on your gran’s dresser. Merrily feeling slightly ashamed that, although she’d known it was most unlikely that the Man would be here today, she was wearing her best coat. Her mother would have agonized, changing tops, changing shoes, inspecting her hair many times in the car mirror, just in case.

‘Who is it safe to talk to, then? Who’s actually living in the house?’

‘Well … nobody. I’m trying to explain, this came from the builder. Canny fella, normally. Or so I thought till he’s ringing us up – Adam, man, I think you’re going to have to find somebody else for this one. I’m going, What?’

Eastgate walked to the darkening window, glanced out briefly, unseeing, turned and came back.

‘We’re good employers, Merrily. In some ways, the best. Never short of tenders and once they’re allocated we don’t get jobs chucked back at us. Doesn’t happen.’

Merrily nodding. They’d be a fairly significant name on a builder’s CV. But it worked both ways, Eastgate said. This builder had a rare feel for an old property. And the Master House itself …

‘See, normally, we’re not interested in anything less than about two hundred acres, and this is, what, ninety-five? But it’s a forgotten bit of old England, right down there on the very edge of Wales. Not much you find these days completely unrestored, hardly touched in over a century. We get to tease out the past. Plus, I’m thinking craft workshops in the barns, the stables, the granary … a little working community, new economic life. And green. Very green. Woodburners, rainwater tanks, sheep’s-wool insulation …’

‘Oh, he loves all that, doesn’t he?’

‘The Man? It’s his number one, and it influences us all, naturally.’ Eastgate shook his head. ‘I’m going, come on, Felix, what is this really about? You sick? Domestic problems? Adam, he says to us, maybe this is an old place that doesn’t want to be restored. His words. Hostile. That was another. One of his team had a powerful feeling they were not wanted.’

‘He pulled out of the whole project because one person thought he—?’

‘It’s a she, Merrily.’

‘Oh.’

The sun had gone, leaving a raspberry hue on the room, but you could still make out the shapes of the fields and the fuzz of hedgerows on the side of Garway Hill.

‘I’m going to leave it in your hands, all right?’ Eastgate gathered up the plans into a black cardboard folder. ‘You take these, they’re only copies. See what he’s putting in jeopardy.’

‘The bottom line being you’d like him back on the job ASAP.’

‘Only if he’s normal. Look, if you want to ask a few questions locally, go ahead. We’ve nothing to hide. Bought in good faith, and what we have in mind is going to be good for the community. I’d just say exercise a bit more discretion than usual.’

Merrily nodded.

‘My watchword, Adam.’

She had a headache.

They walked into the forecourt, deeply shadowed now. Not quite six, and everyone seemed to have gone home. Maybe Adam Eastgate had timed their meeting for the tail-end of the working day so he wouldn’t have to explain any of this to the staff.

All the leaves were still on the trees and it was still warm – too warm. A long, flooded summer and the planet in the condemned cell. At least the nights were drawing in now, the tindery musk of autumn on the air as Eastgate walked with Merrily to the old Volvo. It had been nicked last summer – in the dark, obviously – and then swiftly abandoned, presumably after they’d heard the engine.

‘So – just to get this right – what exactly will you do at the house, Merrily, to, ah …?’

‘Depends what it is.’

‘You work on your own?’

‘I … like to think not.’ She smiled wearily; he didn’t get it. ‘OK, there are a few advisers I can call on, if necessary. Usually when there are people involved who might have particular problems – psychological … psychiatric? When you’re looking at an empty … that is, a house not lived in, as such …’

Oh, the way you shaped and trimmed your glossary of terms when addressing ingrained scepticism. Adam Eastgate cleared his throat.

‘Only I didn’t think you’d be so …’

‘Small? Female?’

‘I was going to say, matter-of-fact about it.’

Meaning, like it’s real.

‘I don’t do it all the time. There’s also a parish – weddings, funerals, rows with the churchwardens.’

‘I suppose medieval was the word I was groping for.’

‘I’m medieval?’ She looked up at him through the fast-thickening air. ‘You’re working for an institution dating back, if I’ve got this right, to thirteen—?’

‘Thirty-seven. Duchy was created by Edward III, to provide an income for his son, the Prince of Wales. The king’s father having been the first to hold the title.’

‘Well … the first Englishman.’

‘And by that you mean … what, exactly, Merrily?’

‘Well, they …’ Flinching at the sharpness of Eastgate’s glance. ‘They had their own, didn’t they? The Welsh. For a long time.’

And even after the princes of Wales had become English there was Owain Glyndwr, in the fifteenth century, still trying to get it back. But maybe mentioning this would not be very tactful.

‘Not my subject, Welsh history. Thank God.’ Eastgate straightened up. ‘Anyway, you’ll keep us up to speed, I hope.’

‘Obviously tell you what I can. Without, you know … breaking any confidences that might arise.’

Not that this was likely. It didn’t seem to be any more than what Huw Owen would call a volatile or a delinquent: the wonky fuse box, the dripping tap – Deliverance-lite.

Merrily unlocked the car.

‘It’s an empty house. If anything’s happening, nobody has to live with it day-to-day. So we’re looking at … probably, prayers, a room-by-room blessing. Or, if a particular and persistent personality is identified, maybe a Requiem Eucharist involving the people most closely involved, present and – where possible – past. Nine times out of ten, this is enough to restore a kind of calm. Adam, why’s it called the Master House?’

‘If anybody was able to explain that,’ Eastgate said, ‘they didn’t want to. Maybe the main house when there were subsidiary farms. Or the local schoolmaster used to live there?’

‘Mmm.’

She had a last look at the hill, where isolated white lights had appeared, its big sisters, the Skirrid and the Sugarloaf fading, uninhabited, into the dried-blood sky.

Adam Eastgate said, ‘Ever get scared yourself, Merrily?’

‘Me?’

Merrily laughed, an unconvincing hollow sound in the stillness. An early owl picked it up, or seemed to, and flew with it as she got into the car.

‘THEN HE WAS back on the phone,’ Merrily told Lol in the pub. ‘Soon as I got in. Barely had time to put the kettle on.’

‘The Duchy guy?’

‘No, the Bishop. Must’ve rung several times already. I don’t think I’ve ever known him this jumpy. I just … I don’t get it.’

She took a drink. Serious decadence: a house-white spritzer in the Black Swan – oak beams, low lights – with one’s paramour. How long had it been before she’d felt able to do this comfortably? Six months? A year?

Seemed stupid now; nobody glanced at them twice – although this was probably because almost nobody knew them. Thursday night, and most of the drinkers in the lounge bar were from outside the village, having drifted in for dinner. Some probably responding to the dispiriting Daily Telegraph travel feature identifying Ledwardine as the black-and-white, timber-ribbed heart of the New Cotswolds.

Like, when did that happen? Couple of years ago, the village was still on the rim of the wilderness. Now there was talk of the Black Swan chasing a Michelin star.

‘The Cotswolds are coming.’ Merrily listened to the brittle laughter at the bar. ‘Ominous. Like a melting ice cap. Rural warming. Feels suddenly claustrophobic, or is that just me?’

Final confirmation of the county’s new economic status: the major investment in Herefordshire by the old Cotswolds’ most distinguished resident.

Charles Windsor, Highgrove.

‘Does he know about this?’ Lol said.

‘Well, that’s what I asked. Didn’t get an answer.’

‘He’d probably be fascinated. Has his other-worldly side.’

‘Only, he keeps quieter about it these days.’ Merrily looked around, making sure nobody could overhear them in their corner, well back from the bar. ‘Since the tabloids labelled him as a loony who talks to plants. Maybe they’ve been advised not to tell him, just get it quietly disposed of. As for the Bishop …’

‘You can see his problem. This is the guy next in line for head of the Church of England.’

‘That didn’t escape me. I suppose it’s as good a reason as any to play it by the book.’

No reason, however, for the Bishop to go adding extra, entirely gratuitous chapters. Full attention, I think, Merrily. We’ll need to get you a locum for at least a week. Move you over there.

And she’d gone, ‘What?’

Like … what? Sounding like Jane, probably.

‘Lol, I don’t want to go and stay in Garway for a week. I just … I don’t see the point.’

‘In which case …’ Orange sparks from the electric candles on the walls were agitating in Lol’s glasses ‘… why not just tell the Bishop to, you know, piss off?’

‘Because he’s a friend. Because I owe him. Because …’

Merrily shook her head, helpless. Lol leaned back. He was looking good, actually. Old denim jacket over a Baker’s Lament T-shirt, which he wore like a medal but always keeping the motif at least partly covered up, as if he could still only half-believe what was finally happening to him. He put down his lager, thoughtful.

‘Suppose I come with you.’

‘You’re touring.’

‘It’s only three gigs next week, just the one night away. I could reschedule … or cancel.’

‘That is not a word we use, Lol. You give anybody the slightest reason to think you’re slipping back …’

A year ago, the thought of three gigs – three solo gigs – would have given him palpitations, night sweats.

Lol looked into his glass, obviously knowing she was right, and Merrily watched him across the oak table, through this haze of love and pride blurred by fatigue. Very happy for him, if concerned that he might just be feeling he didn’t deserve it. Ominously, when she’d gone over to the cottage to drag him out to the pub, she’d heard the voice of his long-dead muse, Nick Drake, from the stereo. Worst of all, it was ‘Black-Eyed Dog’, Nick’s voice pitched high in bleak and terminal despair. Lol had turned it off before he opened the door, Merrily staring at him in alarm but finding no despair in his eyes, just this sense of puzzlement.

‘Besides,’ she said, ‘I’m supposed to be staying with the local priest. They haven’t got a vicar in the Garway cluster at present, so a retired guy’s taking services meanwhile. He and his wife do B. & B. I turn up there with a boyfriend, how’s that going to look?’

‘What about Jane?’

‘Jane stays here. Can’t miss any school at this stage. Woman curate called Ruth Wisdom’s lined up to mind the parish. Work experience. She’s OK. And Jane’s less likely to drive her to self-mutilation than at one time, and she—’

Merrily looked up. A woman was standing behind Lol’s chair.

‘Excuse me. You just have to be Lol Robinson?’

She was tall and very slender. She’d been with a group of women in their twenties, with fancy cocktails, their backs to the bar. All of them now looking at Lol, hands over smiles.

‘Nobody has to be anybody,’ Lol said.

Mr Enigmatic. The woman was leaning over him now, her glossy black dress like oil on a dipstick, one small breast almost touching his cheek.

‘Lol, I just wanted to say, we all went to see The Baker’s Lament at the Flicks in the Sticks special preview, and it was … absolutely enchanting. Especially the music, obviously. But, listen, when I went to buy the CD in Hereford they hadn’t even got it? Nobody had?’

‘Well, it … it all takes time,’ Lol said.

‘And I’m like, for Christ’s sake, this guy’s local? And the manager guy, he eventually admitted they’d had about fifteen orders just that day? Fifteen orders in one morning? This tells me you need to get a better recording company, Mr Robinson. I couldn’t even find a download?’

‘Well, it’s kind of caught them on the hop,’ Lol said. ‘All of us, really. We didn’t actually—’

‘Well, I have to say I just totally love it. Hope you don’t mind me coming over?’

‘Er, no,’ Lol said. ‘No, not at all. Thank you.’

The young woman straightened up. As did her conspicuous nipples. She looked across at Merrily and smiled at her.

Merrily felt small and dowdy and old.

‘He’s lovely, isn’t he?’ the woman said.

Walking back across the village square, Lol avoided the creamy light of the fake gaslamps; Merrily was a pace behind him.

‘Fifteen orders? In one morning?’

‘She was probably exaggerating.’

‘Why would she?’ Merrily pulled on her woollen beret, zipped up her fraying fleece. ‘She doesn’t know you. Although she’ll probably be telling people she does, now.’

‘One small song in one small film?’

‘Not so small now. And you know what? People will remember the song when they’ve half-forgotten the film. Because it’s somehow caught the mood. The zeitgeist … whatever. You have become a cool person, Laurence.’

‘It’s not real.’ Lol was shaking his head, as if to clear it after his two halves of lager. ‘It’s a freak accident.’

Sometimes you wanted to encircle his neck with your hands and …

Over a year now since this young guy, Liam Brown, not long out of film school, had written to Lol, telling him about his self-financed rural love story. How badly, after hearing it on Lol’s album, Alien, he wanted ‘The Baker’s Lament’ on the soundtrack, only wasn’t sure he could afford it. Just take it, Lol had told him, the way Lol would, sending him three versions of the song, including an unreleased instrumental track, and forgetting all about it. Not even mentioning it to Merrily until the middle of July, when the first DVD arrived.

The Baker’s Lament. There on the label, with a bread knife stuck into a country cob. The guy had named the movie after the song.

Shooting the picture with unknown actors who’d formed some kind of workers’ cooperative. Lol and Merrily had watched it together at the vicarage: the tragicomic story of a young couple setting up a village bakery on the Welsh border in the 1960s when the supermarkets were starting to starve small shopkeepers out of business. Following through to the new millennium when the couple were played – and not badly, either – by the actors’ own parents and the village had turned into something like contemporary Ledwardine, the bakery now a twee delicatessen.

The movie was simple and charming and unpretentious, a rural elegy with Lol’s music seeping through it like a bloodstream, carrying the sense of change and loss and a kind of resilience.

Liam Brown was even worse than Lol at self-promotion, and they hadn’t known it had been released – in a limited way, on the art-house circuit – until it was in the papers that an obscure British independent film had picked up some debut-director award at Cannes. Then the who is this guy? calls had started coming in to Lol’s producer, Prof Levin.

Change was coming. New Costwolds, new Lol.

They stopped on the edge of the cobbles, where they’d go their separate ways, Merrily to the vicarage, Lol to his terraced cottage in Church Street. When he took her hand, his felt cold.

‘Apparently, the next question they ask is, Is he still alive? Thinking maybe it’s a forgotten recording from the Sixties, by some contemporary of …’

‘Nick Drake?’

‘It should be him, Merrily. Not me.’

‘Lol, he’s dead. He died in 1974, after a mere five, six years of not being successful. You get to double that … and some.’

She pulled him under the oak-pillared village hall and – bugger it, if there were people watching, let them watch – clasped her hands in his hair and found his lips with her mouth and then unzipped her fleece and tucked one of his cold hands inside.

‘All this,’ she said, aware of the ambivalence, ‘is something overdue. Remember that.’

Trying to banish the image of the girl in the pub, showing him her implants out of a dress that must have cost something close to two weeks’ stipend.

Jane said, ‘You’re a soft touch, Mum. Always were. A doormat.’

‘Thanks.’

It was getting late, but it was Friday night and Merrily had lit a small log fire in the vicarage sitting room. The whole place was colder since they’d said goodbye to the oil-gobbling Aga. Which, while it had to be done, meant she wasn’t looking forward to winter.

‘And I don’t mean one of those rough, spiky doormats,’ Jane said.

‘You’ll like Ruth. She rides a motorbike.’

‘Jeez, if there’s anything worse than a trendy lesbian cleric in leathers with a vintage Harley between her legs … Like, maybe I could arrange to stay at Eirion’s …’

Jane’s voice dried up, and her face went blank. Eirion was away at university now, and she still hadn’t got used to that. OK, it was only Cardiff, and he came home to Abergavenny at weekends, but things, inevitably, had changed.

‘Ruth’s not a lesbian, Jane.’

‘Not a problem, anyway.’ Jane, on her knees on the hearthrug, stared into the desultory yellow flames. ‘I was thinking of giving girls a try for a while, actually.’

Shock tactic. Cry for help. Merrily pulled up an armchair.

‘He didn’t phone, then.’

‘Erm … no.’

‘How long?’

‘Ten days? No problem. I don’t think he was even able to get home last weekend, didn’t I mention that?’

‘No, but I kind of assumed that was why you suddenly had to work on your project.’

‘All that’s gone quiet, too. They may not even start the dig until the spring.’

‘Oh.’

Pity about that. Jane had been hyper for a while after her campaign to stall council plans for executive homes in Coleman’s Meadow. Convinced that the field had once been crossed by an ancient trackway and, amazingly, she’d been right. They’d found prehistoric stones there, long buried by some superstitious farmer. Sensational archaeology, for a place like Ledwardine.

‘He’ll call,’ Merrily said. ‘He’s Eirion.’

‘I don’t care if he calls or not.’

‘Yes, you do.’

‘Like, it’s very demanding, university life.’ Jane didn’t look at her. ‘Lots of guys you’re obliged to get smashed with. Lots of girls to assist with their essays and stuff.’

‘Eirion was never like that.’

‘He was never at university before.’

University. Further education. This could be the time to talk about it again. Just over six months from her A levels, Jane needed to start applying to universities … like now. But Jane wasn’t interested, because that was what everybody did. She kept saying she could feel The System trying to stereotype her. And look at the cost. Tuition fees. Could they afford it? Was it really worth it? Especially as she hadn’t yet decided on a career. Like, you didn’t just do further education for the sake of having done it.

‘You went to uni,’ Jane said, looking down at the rug, ‘and got pregnant before you were into your second year.’

‘We were naïve in those days. Well … comparatively immature. Although I suppose every generation gets to say that.’

‘In which case I must be—’ Jane turned to her, moist-eyed, or was it the light? ‘I must be very seriously immature, then. Pushing eighteen and only the one real boyfriend? That’s not normal, Mum. That wasn’t even normal in your day. That’s, like, almost perverted?’

‘Well, actually, flower, I think it’s really quite—’ The phone rang then, offering her a timely get-out, which she felt compelled to ignore. ‘I’ll let the machine—’

‘No, you get it. Go on. You’ll only sit there worrying until you find an excuse to sneak off and play the message.’

Merrily nodded, got up.

‘It’s a doormat thing,’ Jane said sweetly to her back.

‘Thanks.’

She took the call in the scullery office, padding over the flags in the cold kitchen where no stove rumbled, scooping up the phone with one hand, switching on the desk lamp with the other.

‘Ledwardine Vic—’

‘Mrs Watkins, is it?’

‘Yes, it is.’

‘Adam Eastgate likely mentioned me.’

‘Oh … right. Mr …’

‘Barlow.’ Low-level local accent. ‘Felix.’

‘Right. I was going to call you tomorrow, actually, see if we could arrange to meet.’

‘Tomorrow would be all right for us, yes.’

‘At the house?’

Owls whooping it up in the orchard. Silence in the old black bakelite phone, the kind of phone that could really carry a silence.

‘The house at Garway?’ Merrily said.

‘No,’ Mr Barlow said. ‘I don’t think so.’

‘Any … particular reason?’

‘Well, see … person you need to talk to, more than me, is my plasterer. It’s my plasterer had the experience.’

‘Your plasterer.’

‘I call her that. We’re converting this barn at Monkland, see. We’re in a caravan on the site.’

‘That’s not far for me. It’s just I thought you might find it easier to explain the problem in situ,’ Merrily said.

‘No,’ he said. ‘No, I don’t think so.’

‘You couldn’t spare the time?’

Another silence; no owls even. She waited.

‘I think you’re gonner have to come here,’ he said. ‘We don’t plan to go back, see.’

‘To the Master House.’

This was what he was ringing to tell her? That they weren’t, on any account, going back to the house?

‘That’s correct,’ he said.

She had the feeling that he was working to a script and whoever had written it was standing at his shoulder. She felt another question coming and hung on for it.

‘I was told you … you were the Hereford exorcist.’

‘More or less.’

‘And you’ll have the, um, full regalia, is it?’

‘Regalia?’

‘We’d like it if you came with all the regalia,’ Felix Barlow said. ‘The full bell, book and candle, kind of thing.’

‘Oh.’

‘If that’s all right with you,’ Barlow said.

SHE WAS BEAUTIFUL and shimmery in the mist. Like one of those exotic birds that weren’t supposed to migrate here. Greens and blues in her dark, tangly hair, skin like milky coffee. She stood by the long green caravan, in her pink-splashed overalls and her turquoise wellingtons, calling out when Merrily was close enough for the dog collar to show.

‘Will you bless me?’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘In the old-fashioned way, please,’ she said. ‘That is, with all due ceremony?’

From the field gate, through the lingering mist – a keen hint of first frost – she’d looked as young as Jane. Close up, you guessed she was nearly thirty. Still not Merrily’s idea of a plasterer.

‘I’m serious.’

‘I can tell.’

Merrily looked into eyes which were startlingly big and round, like an owl’s, and widely separated.

‘It strengthens the aura,’ the woman said. ‘Isn’t that right?’

‘I’m sure it must be.’ Merrily parted her woollen cloak to expose the cassock, hemmed with mud now. The full regalia could be a pain. ‘But would it be all right if we talked first?’

‘I just wanted to ask you while Felix wasn’t here. He’s not religious.’ The woman turned away and moved back to the caravan. ‘Fuchsia,’ she said over her shoulder. ‘Fuchsia Mary Linden.’

Which meant that her parents had been either gardeners or big fans of the Gormenghast trilogy. Following her into the caravan, Merrily’s money was on Gormenghast.

She felt tired again, had a lingering headache. She’d awoken a good hour before dawn, her body all curled up, tense with resentment.

Never her favourite negative emotion, resentment. Most times it came hissing like poison gas out of inflated self-esteem – they can’t treat me like this. Seldom objective, never exactly Christi

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...