- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

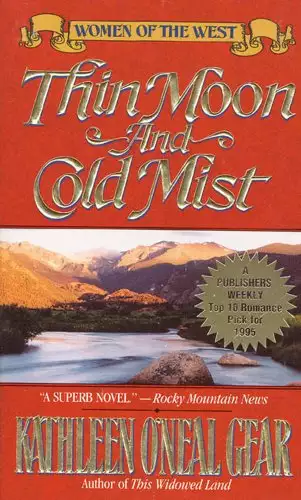

From the USA Today bestselling author Kathlean O'Neal Gear comes a story in the Women of the West series, Thin Moon and Cold Mist

Robin Heatherton is a spy for the Confederacy. Disguised as a young boy, she infiltrates Yankee forces during the Battle of the Wilderness, but when her cover is compromised, she must crawl back to her own lines with vital intelligence. Meanwhile, Union Army Major Thomas Corley, obsessed with Robin ever since her espionage work led to the death of his brother, has vowed to track her down, and to kill her.

Her husband dead at the hands of the Yankees, Robin flees with their five-year-old son into the untamed reaches of the Colorado Territory, where she'll try to work a gold-mining claim-helped only by gruff, handsome Garrison Parker, a Union veteran with no respect for women. She'll teach him some...unless Corley finds her first.

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: June 15, 1996

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Thin Moon and Cold Mist

Kathleen O'Neal Gear

CHAPTER 1

May 1864.

Robin crawled through the underbrush on her hands and knees, quietly, like a cougar stalking prey, and inched her way into a tangled fortress of deadfall. Logs and other debris lay three feet high. She stretched out and pillowed her head on an old gray trunk. The wood had been weathered by decades of rain and wind. The bark was all gone. Worms had gnawed curving trails in the flesh of the trunk and soft green tufts of moss had taken root; she traced them with her powder-blackened hand. They seemed so delicate, so alien to this battlefield. It took sheer force of will to keep her eyes focused on the loveliness of the moss when, over her head, golden sparks flitted glimmering as they blew through the scrub oak boughs on their way to the fire-dyed heavens.

The blazes had begun at dusk, when the wind picked up, and now burned out of control all over the Wilderness. Billows of orange-colored smoke gleamed above the tree tops. They had a strange, eerie beauty, but exhaustion so weighted her she could barely keep her gaze focused on their sparkling glory. She'd been awake for almost forty-eight hours straight.

"Virginia, my poor Virginia," she murmured in a soft, hoarse voice, and the coughing fit that had been building in her chest erupted violently.

She pulled herself to a sitting position and buried her face in her blue sleeve to cover the sound. The action brought forth an agony of aching muscles. The fit took several seconds to pass, and she was terrified that someone would hear.

Throughout the night, desperate commanders had struggled to keep their lines together despite the darkness and spreading fires. The shells that whined across the sky paid tribute to the few artillery batteries that had managed to get into position. The denseness of the scrubby waters brought enemiesface-to-face before they realized it, so the shooting never really halted, and the screams of the wounded and dying formed a horrifying base note to the fire's crackling symphony.

When she could catch her breath again, Robin blinked at the fireflies winking in the branches. So beautiful. Their greenish yellow light contrasted sharply to the red-orange of the sparks tumbling through the sky beyond.

She watched them; they reminded her of campfires she'd shared with her mother when she'd been a child. That seemed like another life. Like another Robin. A child filled with dreams and tenderness, not the cold bitter woman who lived inside her bones now.

Robin sank back against the log. Faces formed and melted in the wisps of smoke that drifted around her. All images from her childhood. Friends from twenty years ago. She whispered their names reverently: "Ambrose ... Ivens ... Wheatley," and a smile touched her lips in response to Wheatley's little-girl grin. Robin was so tired she was no longer certain what was real and what imagined. If she cocked her head she could hear voices seeping from those fleeting mouths. Some sounded frail and old, others tight with pain--her mother's most of all.

"These government people, they are hunted by dead voices and mirrors. You must never trust them, Robin. They are liars. Never believe what they tell you. Fight them. Fight them as long as you live. You will have to--if you don't want to be hunted by dead voices and mirrors yourself."

A full-blooded Cherokee, Sarah Walkingstick Porter had been forced from her North Carolina home in 1838 and begun the Trail of Tears. All of her brothers and sisters had died from disease and her parents from starvation--because they had given every scrap of their own food to their ailing children. Though Sarah had married a white military officer and left the Cherokee to live in Richmond, she had always considered Robin to be an Indian. She'd schooled her daughter in Cherokee legends, their knowledge of plants and animals, and warned her "never to forget" what the white nation had done to her people.

Robin let her chin fall to her chest and inhaled a halting breath. But, mama, oh, mama, I want to go home. I should be taking care of my little boy. I want to go home so badly I ...

She jerked when a single shot split the night, followed by a spatter of blasts so near and loud that she dared not breathe. Ragged screams followed the volley.

A riderless horse raced past her, its nostrils flaring as it crashed through the forest and blended with the night.

Robin got on her knees and peered over the fallen logs, trying to see through the blinding gloom. Her blue uniform stuck to her tall, slender body in sweat-drenched folds, making the thick bandage that wrapped her chest and flattened her breasts feel like a band of iron.

Where were the men? And which army are they fighting for?

For two days she'd been using her pocket compass to chart a course through the wilderness, hoping that when the time came she would be able to find her way back to her own lines. She'd begun the attempt last evening and had stopped to rest only when she'd felt certain she had made it to safety.

But I may still be behind enemy lines. I cannot rule out that possibility.

The lines had been slithering back and forth like a den of snakes. In the doghair chinkapin, hazel, and head-high berry brambles, a soldier could get turned around and never know again which direction he faced.

This battle bore little resemblance to organized warfare; it was more like bushwhacking on a grand scale. Invisibles fighting invisibles. No one could see more than a few feet ahead. Even a Southern boy, accustomed to moving through such country, often couldn't determine where he stood in relation to his company. But the Southerners fared a good deal better than the Northerners. Half the Union army came from tame farmlands or cities, and this wild second-growth country seemed to have affected them like a hard blow to the skull, leaving them hopelessly dazed. Yesterday, Robin had followed one company as it thrashed through the jungle, firing muskets at nothing until every ball was gone. She'd heard stories of people who shared dreams. These men seemed to be sharing the same horrific nightmare.

More shots. Panic fire, as if from men who'd been surprised by the enemy.

"Cease firing!" someone shouted. "Cease firing!"

"Who gave that order?" another yelled. "Don't listen, boys, he's the enemy, I tell you! Kill him! Kill him quick!"

Robin hit the ground as streaks of flame shot through the dense trees. They came from no more than thirty paces away.

"Cease firing, goddamn you! You're shooting at your own men!"

The fire's haze mixed pungently with the smoke of belching muskets; she could taste the bitterness of gunpowder on her tongue. When hooves thundered, Robin rose, braced her pistol on the deadfall, and squeezed the trigger, taking up the slack, ready to fire.

A big bay horse thundered toward her. A Union colonel swayed in the saddle, almost falling off. The horse leaped a sapling that had been felled by gunfire, whinnied, and swung south, disobeying the brutal reining of the man who held on with one hand while he used his other to fend off the overhanging branches. His wound was clearly visible. The minie ball must have struck him in the back, for there was a gaping exit hole in his stomach. Dark blood coursed over his legs, soaked his pants, and trickled down the horse's sides as they disappeared into the haze. Another horse came crashing in nearly on the bay's heels, a sorrel, ridden by a Union lieutenant.

The dark-haired lieutenant saw Robin and shouted, "Where'd he go, boy? Which way did the colonel's horse go?"

"That way, suh!" she answered and ran forward a few paces to show the way through the forest.

"Follow me," the lieutenant ordered. "I may need help." And he vanished. Deadfall cracked like cannon fire in his wake.

Robin shoved her pistol into her waistband, feeling sick, sick to the death of the foul scents and unbearable sights of war. She slung her haversack over one shoulder and trotted through the wind-blown weave of shadow and firelight. She found the lieutenant with his sorrel standing shoulder-to-shoulder with the bay, fighting to hold the colonel on his saddle.

"My God, Colonel," the lieutenant said. His thin aristocratic face had been bleached by the firelight, making his eyes seem huge dark pits encased in an old skull. "I'm sure those were our men. I mean I know the lines are all twisted up in this wilderness, but I thought I saw blue uniforms. I ..." His voice broke. "I'm sure they must have been ours, John."

The colonel nodded, using what strength he had left to stay on his mount, but it soon failed him and he slid sideways into the lieutenant's arms in a faint.

"John!"

The lieutenant's horse bolted and both men tumbled to the forest floor.

Robin ran forward. "Hyah! Go on, move!" she yelled at the prancing sorrel to keep it from trampling the officers. It dashed away into the thicket as she grabbed for the reins of the colonel's bay.

The lieutenant ordered, "Hurry it up, boy! Tether the colonel's horse and get over here. He's bleeding badly!" He gently lifted the colonel's head onto his lap. "John? Oh, John, good Lord, stay still. Try not to move."

Robin led the bay a short distance away and tied the reins to a tree, then ran back and knelt by the lieutenant. He had a straight nose and wide blue eyes, framed by brown hair. Soot coated his skin and uniform. He'd lost hishat somewhere. The two men shared a resemblance. Cousins? Brothers? Both looked to be around twenty-nine or thirty. Five years older than Robin.

"Don't try to rise, John!" the lieutenant half-shouted when the colonel struggled to sit up. "We're ... we're safe here. Rest easy, easy ..." He smoothed a hand over the colonel's brow until he calmed down, then took out his knife and sawed through the man's bloody shirt to examine the injury. Ropes of intestines had been forced through the wound by the colonel's fall. Robin lowered her head as the lieutenant touched them. "Oh, John," he whispered. "I tried to make the men stop firing. They wouldn't stop. I tried ... don't know why they wouldn't stop. Don't die, John. God, please don't die!"

Robin remained quiet, waiting for orders that never came. Finally she said, "Suh, shouldn't we binding up the wound? To stanch the flow o' blood?" It would do no good, but it would give the young lieutenant something to do while he regained control of himself. And she needed him to be in control, so he could think straight.

The lieutenant swung around with fire in his eyes. "Hell, no, boy! For the sake of God, go and find a surgeon! And bring stretcher-bearers! This wound is no trifle!"

Gently, Robin answered, "No, suh. I can see that, suh. I was just thinking it might be well to bind the wound or it could be useless to go for the surgeon. If you sees what I means, suh."

The lieutenant blinked, and lowered his head. "Oh, yes ... yes, of course. But ... he's ... I don't ... do you think binding it ..." His mouth hung open, moving in more words, soundless now, or maybe it was just the effort to choke back the tears that filled his eyes. He lifted the colonel and cradled the man's broad shoulders in his own shaking arms. Water beaded on the lieutenant's soot-coated lashes.

"You keep a holding him like that, suh. I'll care for the wound."

Robin unslung her haversack and took out a roll of bandages. She carried a roll at all times, to disguise the lines of her bosom. Now, she tipped the colonel's torso so she could slide the roll under his back and come up around his torn stomach. The vile odor of ripped intestines forced her to hold her breath. Will the killing never stop? Couldn't the Yankees see that the South would fight until every man between the ages of ten and a hundred lay cold and dead--and many women too? Robin knew of at least fifty women, dressed as men, who had taken up arms to fight side-by-side with their male counterparts. Battlefield nurses had told Robin they had treated hundreds of women soldiers.

She forced a breath into her lungs and wrapped the colonel's wound sevenmore times, before splitting the end of the bandage and knotting it. Blessed Jesus, so much blood. The white fabric went crimson immediately. When she sat back, she pushed her cap up, showing a kinky fringe of hair.

"Did you see them?" the lieutenant asked, searching her face. "The men who shot at us? Were they ours, or Rebs?"

Robin shook her head. "I didn't see nothing, suh. Just heard the firing and hunkered down to wait, that was all."

"You were scared?" It was an accusation.

"Yes, suh." Robin hung her head in shame. "I was scared real bad."

The lieutenant paused, then his voice came out soft, forgiving. "It's all right, private. We're all scared."

He began rocking the colonel in his arms, like a mother trying to get a newborn to sleep. He kept his eyes closed a few moments, then asked through a shaking exhalation, "Where are you from, boy? You're about as black as Mississippi tar."

Robin tucked what was left of her roll of bandages back into her haversack, and her fingers brushed the cool vial of silver nitrate, in weak solution, which she used to turn her skin its rich mahogany color. It didn't take much. Her half-Cherokee blood had given her a chestnut complexion to begin with. But since many of the Cherokee, Osage, and Seminole were fighting for the Confederacy, someone might have been suspicious about her Indian heritage. No one ever thought twice about a young Negro soldier. "That's 'bout right, suh," Robin answered. "I come from the coast o' Luzianna."

"A runaway slave?"

"Yes, suh, but now that I'm a free man--"

"You're not a man, son. You're nothing but a boy. You haven't grown whisker one yet, have you?"

Robin shook her head. "No, not yet, but my brother didn't grow no whiskers until he was 'bout sixteen. So I guess I got me some time."

"Sixteen? How old are you, boy? Fourteen or fifteen? Lord God, how'd you get in this army?" She didn't answer, and he let out a tortured breath as he shook his head. His eyes drifted back to the dying man in his arms. "This godforsaken Army of the Potomac. I wish I'd never--" The shrill screech of a shell cut through the fire's glow. "Get down!"

Robin landed on her belly and covered her head while the lieutenant scrambled to shield the colonel's body with his own. The earth heaved and groaned when the shell struck, shaking the ground like a monstrous quake. Uprooted trees and clods of dirt flew through the air, slamming into othertrees before thudding to the ground. A rain of dirt cascaded down upon them. The colonel's horse screamed and reared. Tearing its reins loose, it pounded away into the depths of the forest.

Robin started to shake. I've got to get back to my own lines, or I'll never see my son again. Before he'd left to join General Nathan Bedford Forrest's command in Tennessee, her husband, Charles, had gotten word to her that he was leaving Jeremy with his mother in Richmond. The child was five years old. I'm sorry I missed your birthday, Jeremy. I'll be back soon. One trip to Wilmington to meet Rose's ship, then home to Richmond for Christmas. Daddy will be coming home, too, Jeremy. A few months, that's all ...

Rose's note from England had boasted that grand news would follow, news that would turn the tide of the war. But Robin couldn't let herself believe it. She'd heard dozens of desperate stories lately, though she had never known the great spy, Rose O'Neal Greenhow, to distort the truth just to bolster the courage of the troops.

At the onset of the war, Rose had operated a spy ring out of Washington, D.C. that included, among many others, F. M. Ellis, a secret service officer on General McClellan's own staff; James Howard, a clerk for Lincoln's provost marshal, M. T. Walsworth, in the adjutant general's office; and Mr. Callan, who worked for the Senate Military Committee. She had also plied her trade with Colonel E. D. Keyes, secretary to General Winfield Scott, then General-in-Chief of the Union Army. It had been Keyes who had given Rose the information on the size of the federal forces that would move on Bull Run, the route of their advance, their battle strategy, and even a copy of General McDowell's actual order to his troops.

No, Rose's professionalism was beyond question. If she said her news might turn the tide of the war, then it well might. Hope, long dormant in Robin, stirred. But just a breath, like a faint whisper ...

"Forsaken, forsaken," the lieutenant whispered so forlornly that it made Robin roll over to stare at him. "God has forsaken us, Private. We'll all be lost in this struggle."

She sat up and brushed the dirt from her uniform. It took a deliberate effort of will to steady her voice. "We ain't forsaken, suh, not yet. I was listening to some men what come by earlier, running fast from the fires. They was saying that we was winning dis battle. Yes, suh, I heard 'em right, too. They said Bobby Lee would be getting his due in the morning, 'cause Mister Unconditional Surrender hisself had a good plan."

The lieutenant tenderly touched the colonel's pale cheek and his youngface slackened in shock. Robin could see the man's dead eyes, open halfway, sprinkled with bits of forest duff. Lucky, lucky, lucky. Too often, she'd witnessed belly wounds that brought suffering for days.

"Oh, no ... God, no, please." In a choking voice, the lieutenant called, "John? Oh, John, I'm sorry. I tried so hard to make the men stop shooting. I ... I tried ..." He clutched the colonel's clothing with trembling hands.

The fire flared somewhere behind them and cast a lurid glow over the tiny clearing where they sat, revealing things Robin had not noticed before: Moldering shreds of uniforms, blue and butternut, twined through the underbrush like perverted vines; tarnished buttons glittered in the leaves, and here and there a dirt-caked bone protruded from the dark forest floor.

Robin closed her eyes. Had a year truly passed since the battle of Chancellorsville had been fought on these very grounds? It seemed just a few heartbeats ago. General Stonewall Jackson had been shot just east of this spot and later died from his wounds. Nearly thirteen thousand Confederate soldiers had been killed or wounded. She'd walked among them, laughed with them, starved with them--those ragged, exhausted, brave men who had fought to the death to protect their homes and families from the Northern invaders.

Robin picked up her pistol and wiped it off with the hem of her jacket before lifting her eyes to the lieutenant again. She ought to kill him ... But he'd put the colonel's limp hand to the uniform over his heart and seemed to be biting his lip to muffle the mournful sounds coming from his throat. Jackson had said that the only way to win this war was to kill them all ...

Robin holstered her pistol. This young man might know something that would help her side.

The war could not go on much longer. Southern troops were marching barefoot now and surviving on one-third pound of meat and one pound of bread a day.

The lieutenant's composure broke and he wept aloud. Robin rose and went to him, laying a gentle hand on his shoulder. He looked up at her with swimming eyes. "He's gone. My brother's gone. My God ... what will mother say?"

She answered, "She'll say she was mighty glad you was here when it happened, suh. Nobody wants to go it alone. Now, please, let me he'p you. Let's be burying this good man so you can get back to headquarters and tell 'em what's happening in this wilderness."

The lieutenant wiped his eyes on his sleeve, smearing the soot into blackstreaks, and managed to suck in a breath. He sat motionless for another minute before he said, "I would appreciate your help, Private."

They dug the shallow grave in silence, Robin using her tin drinking cup while the lieutenant used his knife, both listening to the far-off cries of men too injured to run as the fires neared. The lieutenant broke into sobs occasionally, but never slowed his labor. The ground was so soft, it took no more than half an hour.

They lifted the colonel's body and eased it into the hole. As they shoved the dirt over him, Robin said, "Have you heard 'bout Gen'l Grant's plans for the morrow, suh? Is the gen'l going to tell us how to whip these Rebs?"

The lieutenant sank back on the old brown leaves as though exhausted. He ran a hand through his hair while he stared at the fresh grave. "Only God knows the answer to that, soldier. My brother told me he'd received some intelligence on troop movements late this afternoon, but not much. It's such a damned snarl out here."

"Yes, suh, that it is. But we must be winning some of the skirmishes ... ain't we?" she asked anxiously.

"Oh, yes, we are. We are, son. We cut A. P. Hill's corps to ribbons today. I heard tell that those graybacks broke and ran like ticks thrown into a fire." He tried to smile, but it was a wan attempt. "We outnumbered Hill. He didn't have a chance against us. Hancock will be going in to finish him off at dawn tomorrow."

Robin wet her chapped lips. "That so? Hill seems mighty tricky to me. How's Hancock planning on routing him?"

The lieutenant shrugged. "I don't think even he knows for certain. John said something about how Hancock would be moving his men down the Orange Plank Road toward old Widow Tapp's farm. It's the only real clearing for miles. If it can be seized and held, Lee's right can be destroyed, and so will begin the destruction of his army."

Robin grinned. "That sound plenty good to me, suh. I don't like fighting these Rebs one bit. They got more lives than a barn cat."

"Yes, it seems they do, doesn't it?" The lieutenant met her eyes, then looked away.

Lifting her haversack, she slung it over her left shoulder. Firelight penetrated the tapestry of tree and brush and sent long ghostly fingers over the fresh mound of earth. The fingers advanced and pulled back, then advanced again, as though hesitant to touch the grave, but drawn by the scent of death. Her mother had believed that fire had a soul. On terrible nights like this,Robin half-believed it herself--a greedy, ravenous soul that thrived on the screams and pungent blood. The flames would be here soon enough, and the thin sheath of soil they'd piled over John would not protect him from that hungry beast. At least he was dead. Dozens, perhaps hundreds, lay wounded and alone in the fire-bright darkness, and they would face the beast alive ...

"Suh," Robin said, "I reckon we ought to be moving on. If you're up to it, suh?"

"Yes, I--I am," the lieutenant replied as he stroked the edges of the grave. The lines around his eyes had pulled tight. "Let's get started before--"

A storm of grapeshot ripped through the forest around them, mowing down saplings and cracking off thick boughs that pounded the earth like the footfalls of a giant. It lasted but a second.

But when it had ended, the lieutenant jumped to his feet, and glared wide-eyed. "Fire!" The shot had sparked off the rocks and started flames. "It's building fast. Get up, boy. Now!"

Frantically, the lieutenant ran northward, searching for a way around the fire, and Robin took the chance and sprinted in the opposite direction. She shouldered into a dense bramble of vines where warm shadows enveloped her. Quieting her breathing, she trained her ears on distinguishing footsteps from crackles of flame.

The young officer yelled, "Boy? Boy, are you all right? You coming, boy? Where are you? Boy ... you--you hit?" His steps cracked in the dead twigs, going westward now. "Boy? ... Boy, the fire's spreading!"

The wind fanned the flames into a large blaze, but when she leaned out of her shroud of vines she saw no one, nothing, except the fire licking hungrily through the underbrush, climbing tree trunks, singeing leaves. The young lieutenant was gone.

An icy chill settled in her stomach. She had to reach A P. Hill tonight, to warn him about Hancock's attack plan. But had the mosaic of fires blocked the path she knew? She could not spend all night trying to veer around blazes--it would take too much time.

You're going to have to establish a heading and try to keep to it. Removing her compass, she took her bearings, figuring about where Hill should be encamped.

As she hurried along a narrow deer trail, she pulled off her kinky wig, unpinned her hair, and let the waist-length black wealth fall down her back. She stuffed the wig into her haversack and removed a pink flowered skirt that she slipped on over her blue pants. After rolling up and tying her coat aroundher waist, she looked like nothing more than a poor Negro slave girl from one of the nearby farms who'd gotten lost in the foray--though they'd think her half-white or half-Indian because of her straight hair and finely chiseled features.

No man worth the name would shoot a woman.

Unless, of course, he discovered her true identity. Then it would be a miracle if she lived long enough to be justly hanged.

She wiped her sweating palms on her skirt and slipped her revolver from its holster. A man might not shoot her, but she'd kill anyone who tried to stop her from reaching A. P. Hill before dawn.

As she broke into a run and headed down a steep incline, the pall of smoke grew thicker, swirling around her in great gleaming tufts. She picked up speed, racing so fast that she barely heard the agonized voices that flitted like elusive wings across the distances.

Copyright © 1995 by Kathleen O'Neal Gear

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...