- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

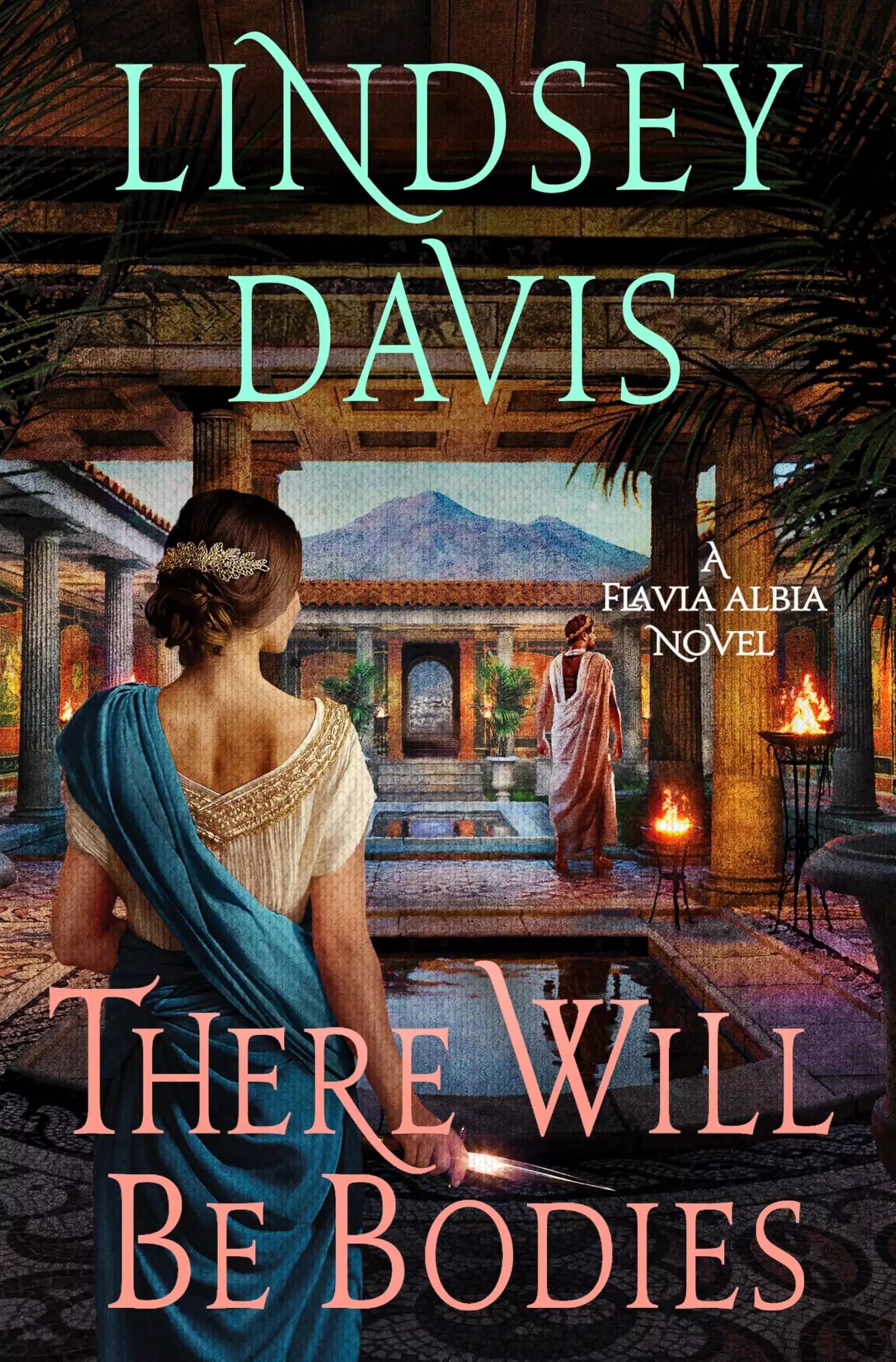

Synopsis

A decade after the destructive eruption, Flavia Albia finds herself investigating family secrets and possible crimes buried in the ash of Mount Vesuvius.

In first century Rome, Flavia Albia—daughter and successor to Marcus Didius Falco—is once again faced with uncovering the truth. Quite literally. Only ten year’s previous, Mount Vesuvius erupted and rained ash down about the Roman cities and towns along the Bay of Naples. But while some cities were destroyed, others were merely badly damaged. And the uncle of Flavia Albia’s husband seizes the opportunity to buy a villa…cheap! It just has to be dug out of the ash, and restored. Oh, and any bodies uncovered, including the previous owner, given a proper burial.

And as the Villa is being renovated, there are indeed bodies found. But one is not like the others—instead of buried in the ash, the previous owner’s body is found in a locked storeroom and Albia is immediately suspicious that he didn’t die in the eruption. With suspicious caretakers, a large inheritance, untrustworthy friends and a Sicilian pirate sniffing around, Albia must solve the riddle of a long ago death, maybe murder, to prevent another one.

Release date: July 22, 2025

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

There Will Be Bodies

Lindsey Davis

Chapter 1

‘There will be bodies. It is only fair to warn you,’ my husband told his workmen. Some contractors might have kept quiet, but he liked to be open about risks. Mind you, he had brought me in on the discussion in case he needed support. I won’t say the men were frightened of me, but they were generally wary.

When Tiberius Manlius took over their nearly bankrupt company, the existing team saw it as a fad. But he could recognise the right end of a chisel; they had learned that now. And for men with mortar on their boots, being employed by a toff in a laundered toga was better than losing their jobs.

Not that he was soft: ‘If anyone prefers to stay behind in Rome, I won’t be paying a retainer.’

‘That’s a joke?’ Sparsus, the apprentice, was traditionally young and daft.

‘Afraid not. Are you turning down a free holiday?’ This really was a joke because Tiberius had explained that the project at Neapolis would be hard work. It was a favour to his uncle, a man who had grown rich through screwing his customers and who tended to view even close relatives as people to be played.

Uncle Tullius had bought a house. It was uninhabitable, but he presumed that, with a nephew in the building trade, he could have it very cheaply restored. ‘No frills, just a basic clear-out. At cost, of course,’ he had said airily. That meant we should not expect to make a profit.

Tiberius was humouring him. This uncle controlled the family finances: co-operation was the safest approach. Keeping him sweet applied even though the vague ‘clear-out’ would involve excavating volcanic material that had been dumped in and around his new property during the disastrous eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Most walls were still standing, Tullius had been assured.

‘That could be a lot of pumice, Legate!’ observed our clerk-of-works darkly.

Tiberius nodded. ‘Larcius, it’s clear how Tullius managed to nab this place at a knock-down price. All the easy-rescue projects were knocked off years ago. But we’ll be fine, don’t worry. I deliberately haven’t told him about the sky-high billing rate we devised for “hacking out rubble” on our Eagle Building job. You know Albia had the agent paying for protective gear and specialist insurance.’

Larcius had liked that. We still had equipment from the Eagle Building job stored in the yard for future use, while the supposed insurance premium had financed an end-of-project feast.

‘Helmets. First-aid supplies. Danger money . . .’ I was inventing in the same merry way I had bamboozled our customer’s agent. A year ago, I had known nothing about

demolition and restoration, but I learn fast. Like most Roman wives I was now a lead player in the family business. Like most, I was ruthless financially.

‘Custom and practice!’ Tiberius winked at me. ‘If we don’t know what the custom is, we’ll make it up as we go along.’

A year ago, he was a leisured playboy, until he came out of his shell when his uncle financed his election as a magistrate. This shift into the political world was intended to raise their business profile, but Tiberius had taken the role seriously. Uncle Tullius had had a big surprise over his nephew’s approach to public service. But the building trade was different: he might have another shock with his ‘honest’ nephew’s approach to working on the new house.

My husband was a practical man, even if some people said his good sense had let him down when he married me. After six months, he was still claiming that was the best thing he had ever done; I just smiled mysteriously.

In theory, if Tiberius Manlius ever decided he had made a mistake, my own work as a private enquiry agent ought to equip me to bring about a painless divorce. I was realistic, however. Why do lawyers die without making their wills? How come doctors are killed off by coughs they have never bothered to treat? Meanwhile, informers’ marriages often fall apart: the financial stress is terrible, children are permanently damaged, their dog runs away, and they certainly don’t bother with any pretence that the split is so amicable they will stay friends.

Our dog could sleep soundly in her fancy kennel, I thought. Despite all I had learned from tragic clients, I envisaged

Tiberius and me sticking it out, hand in hand, until we were doddery. I supported him with love and loyalty, while he showed plain determination. Marriage had been his idea, and he could always make his ideas sound reasonable. That was why most of his men agreed to travel with us to the new site. Sparsus, the excitable apprentice, even pestered us about what any corpses they uncovered might look like.

‘To be honest, I don’t know.’ Tiberius had given it forethought. ‘It’s been ten years. Victims were buried deep in compacted materials that were very hot. I can’t tell you whether any remains in that old crud will be decayed or preserved. We shall find out soon enough. All Tullius knows from the owner is that some people who lived in the house were never seen again. If we do come across victims, we have been asked to collect any evidence of who the poor souls were.’

Serenus, who was an experienced labourer, pulled a face. ‘And what are we supposed to do with them?’

‘Chip them out as best we can. Then dispose of them reverently.’ It sounded as if Tiberius himself was making this rule. I suspected he had not even asked the previous owner what he wanted done. Bodies would be treated with respect, because it was the pious way to behave. I had married a good man. That was a surprise to me, just as my love of his benign character surprised him. He had feared I wanted someone rougher. ‘The seller will pay for basic memorials for slaves,’ Tiberius reported. ‘But he did tell Uncle Tullius that he wants to hold a full funeral, in the event we are able to identify his long-lost brother.’

A long-lost brother? That was news.

Hmm. In my experience such situations are never as clean-cut as people suppose. However, tracking down a missing relative sometimes brings in business for me, so this could be welcome. ‘Will the vendor give us a finder’s fee?’

‘I suspect not.’

Even young Sparsus, ever curious, was quick to spot the oddity: ‘Chief, when fiery lava started flying around, why didn’t this brother jump into some crack piece of transport and make a bolt for the hills?’

Exactly. Still, relatives can be hard to fathom. Half the time in my investigations, people who have disappeared did it to cause trouble in their family.

‘Vesuvius had created utter panic.’ I must have sounded sombre. I had been there afterwards. I had told them that, though so far not dwelled on it. ‘What came out wasn’t slowly creeping lava that people could run away from, but ferocious explosions of rock, ash, mud, gases and heat. If the brother did grab valuables and try to escape, as many people desperately did, some accident might have befallen him. Dashing off in a direction that looked passable, he could have ended up in a village where he wasn’t personally known. When his lungs or heart gave out, after he’d breathed in poisonous air and dust, no one sent word to his family. But there was anarchy on the roads. He may never have reached safety. All the social rules broke down. This man could have been set upon for his “crack transport”, then he was killed and dumped – one more anonymous victim beside those crowded escape routes.’

something for you to investigate, Albia!’

We had already agreed that I was going with them. I cooed back, like a doe-eyed housewife, ‘Thank you, darling!’

I made it sound as if I had absolutely no interest, but he knew me: I was already wondering.

The cut-price villa was at Stabiae, on the southern side of the Bay of Neapolis. We had been told it stood high on the cliffs above the town and port below. Such a grand position must have made a stupendous observation point when Mount Vesuvius exploded – although rather too close for comfort if you were trying to stay alive.

Stabiae and its residents had survived the first day, but as the eruption increased in violence, people either upped and fled in a hurry or they were trapped in deadly fumes. The killing waves of heat and gas that wiped out the famous towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum did reach as far as Stabiae, although with less force. Where Tullius had bought, at the eastern end, many huge, fabulous villas had been built in a tight-packed ribbon along the heights; some became smothered in volcanic debris as high as first storey ceiling level. Tiberius reckoned from advance research it could be fifty feet or so deep. Even so, Tullius had been assured that many along the Surrentum Peninsula were not buried as deeply as farms and towns closer to the volcano. Creeping back home after three days of terror, people could still see through the silence and darkness where the little town of Stabiae had been.

Elsewhere it was different. That’s famous. I had gone to Campania afterwards with my father, pointlessly searching for relatives. It had a profound effect on me, which I would have to address once I was ready. Falco had known the area so he could hardly believe what we found. Herculaneum was so deeply buried it was gone for ever. At Pompeii only the very tops of the tallest buildings showed above maybe seventy feet of tephra. Occasional roof fixings hinted at monuments below, or we could sometimes decide the position of streets because lines of excavated holes showed where returning householders or thieves had already tunnelled in. A lot of property was being retrieved. Opportunists were everywhere – they must have begun scavenging while the infill was still warm. But the famous town had died. Thousands had perished. Falco and I never found the people we were looking for.

As ever, the rich had managed compensation for their grief. Like many well-off Romans, Uncle Tullius had previously owned holiday homes on the bay. Like others, he was now thinking that after ten years things ought to be improving, so that playground for the wealthy ought to become available again. Plutocrats don’t accept losses easily, not even when they have to blame the gods.

In the immediate aftermath, Tullius sold his house at Neapolis to an imperial commissioner; he did so as soon as he heard how the government was providing funds to rehome refugees, and he made a packet, naturally. He had also owned a villa near the harbour at Herculaneum, but he lost that. Herculaneum’s port was first smashed up by waves, then the town above was engulfed by enormous torrents of boiling mud and rock. The shape of the bay altered. Soon, nobody would even remember where Herculaneum had been.

balcony and sweet sea breezes, must be permanently written off. He had loved that villa, or so it was said (‘love’ was never a word I associated with Uncle Tullius). Eventually he jumped at his accountant’s suggestion that buying a new place would be good tax management. Stabiae was being recommissioned as a larger port now Pompeii had gone. Sailors could no longer land at the old Marine Gate and walk up into a racy town under the protection of the goddess Venus. Stabiae had once been smaller and staider: this minor beach and spa town was the coming place. Taking on a semi-derelict property there would make Tullius Icilius a social benefactor, giving support to the devastated community.

People did not usually see him as sentimental. Any thought of him as a benevolent old buffer would soon disperse if you met him. However, among men of the same type, he passed as canny and trustworthy – well, as much as any of them.

The family money had been made over several generations. As Rome had expanded into an aggressive empire, its citizens gained access to new provinces that either wanted what Italy produced or produced what Italy wanted. The Icilii had recognised that, but saw no reason to face the burdens of shipping and overland transport, to struggle with negotiating in trade markets, to defend against pirates and brigands, or to bribe officials. Rather than acquire a colicky mule-train or pay a dubious wagon-master of their own, they bought a warehouse in Rome for other people to hire. One building, well run and astutely priced, was soon added to until much of the Aventine Hill above the Lavernal Gate was neatly clothed in their stores.

According to Tullius, the warehouses ran themselves, although I knew he still contributed a personal input. Under a detached veneer, he worked hard, managing alone for years because he had never let his nephew be other than a cipher. Tiberius was allowed a palaestra subscription and an account with a scroll-seller, but he was kept away from the ledgers. Tullius controlled their joint fortune.

By the time I met him, Tullius Icilius was a well-known figure on the Aventine. He was in his sixties. Wealth had made him heavy in the midriff and ponderous in manner; success let him be scathing of others. He had never married, which was for selfish reasons. Why bother? What would be the point of a wife? A woman in the home would only spend money and try to poison him off. We were sure he did not deny himself pleasure but, after all, when his only sister died she had bequeathed him a reliable adult heir in her son, Tiberius Manlius. There had been a daughter too, who also died, leaving behind three little boys, two of whom we were fostering. Tullius had no need to be disturbed by infants in his own quiet house.

He lived over by the Street of the Plane Trees, above the riverbank Emporium where his tenants would buy and sell their expensive goods. It may have felt as if he was personally supervising their safe storage, though he paid managers to do that. Yet he maintained a presence, in a large private home with understated elegance. It might have suited a senator, though such a pomposity might complain it was cramped for entertaining. Tullius only entertained if there

was a business advantage. When he did, he and his guests tended to turn up unannounced and take pot-luck. Mind you, his well-organised staff always ensured that an extremely generous pot would be available, with all the trimmings, and the best fish sauce that men of business could require. His was a comfortable home, though people were lucky to be invited. It was different for us, because Tiberius had lived there for half his life so he would stroll in and out as he wanted.

The Icilii had always been plebian; Tullius saw no reason to waste money on upgrading to the next social level, though he did push his nephew into that official post last year. They had used traditional methods (dinners, favours, donations) to make Tiberius an aedile. After he startled everyone with his unexpected diligence, their standing increased until his uncle screwed his eyes into a piggy expression and grunted that he wasn’t planning to do it again, but it had been worth splashing some cash.

He was less pleased when Tiberius decided to marry me. At the same time, Tiberius bought a building firm. His late father and grandfather had been successful in this line, so Tullius set aside his objections. At least he could exploit Tiberius and his men as cheap labour at Stabiae.

‘The old sod seems to think we come free,’ grumbled Tiberius – though he was putting up with it.

He had a vague responsibility for acquiring the villa. In some mysterious way that I never winkled out, my husband’s year as a magistrate had improved his uncle’s

balance sheet. Out of concern for Tiberius, who was one of Rome’s few honest men, I preferred not to know how his uncle had taken advantage of his stint in public service. No one but me ever seemed suspicious. Once a businessman is accepted as honest, his reputation usually carries on for life. Perhaps, since questioning appearances was part of the work I did, I was too quick here. Perhaps a completely innocent assets-review had led the uncle to purchase his supposedly desirable property at Stabiae. Especially as he believed it was a bargain.

He had snaffled it from a crony. Tullius would usually wheel and deal at bar-room lunches, where married men took refuge away from home stress, or at off-colour dinners in bachelors’ houses: places where peculiar perfumes were sprinkled and foreign flute-girls poured the drinks. I had assumed all his contacts were long-term. People he had known for years, whose families he had heard about even if he had not met them. Men whose lives, wives and trading acumen he could evaluate. Those whose bankboxes his own financier sniffed out and slyly priced for him. People he called ‘solid’. Perfectly safe to rely on if he was purchasing a property a hundred and fifty miles away, sight unseen.

It turned out that was not the case. Tullius knew Sextus Curvidius Fulvianus only slightly; he was the proverbial ‘friend of a friend’. Tullius could barely describe the villa, let alone discuss his vendor’s personal circumstances. However, to assist my husband with pre-planning the works, he invited us to dine at his house, where we could have a look at floorplans and meet the vendor.

‘See what you think, Albiola,’ my husband muttered to me. I am always drawn to an enigma, but he could be even worse. He was not referring to the villa’s layout. He meant is this man a crook?

My initial thoughts were neutral.

Curvidius Fulvianus arrived slowly. His movements were stiff, but he had made it into his seventies. He had a boyish face, despite his years. Short hair, still brownish, came forwards on a domed forehead in a natural fall, not a vanity cover-up. He was fairly tall, not gaunt but no spare flesh.

To reach his age, his life must have been fortunate. He might be rich, though had not acquired glittering sesterces by heaving about big sacks and amphorae. Stronger staff, who no doubt died younger, must have done that, while the sheltered Fulvianus busied himself with contacts and contracts, or flights into two-timing the Treasury.

It went without saying that everyone we ever met in the company of Uncle Tullius finagled their fiscal affairs. Sales, inheritance, manumissions, customs dues – and absolutely the imperial census. They rarely boasted, but tax fiddles were a staple of life for these men. That was the main reason Tullius and my father had managed a meeting of minds when Tiberius and I had announced our intended marriage. Falco’s stated profession these days was ‘auctioneer’, so he was adept at massaging money in inventive ways. He pretended he never did it; Uncle Tullius knew what that meant so they shook hands on the wedding that neither could avoid. They would make aloof blood-brothers, yet they could discuss a flagon of Falernian without coming to blows.

Of course, afterwards Pa would grouch that Tullius was an idiot: last night’s wine had been Fundanian.

For his vendor, on our getting-to-know-you evening, Tullius served Alban. No wine buff would exclaim over that, but it would give guests a secure feeling; their host probably did not drink Alban every day (unless he was a consul). In snobbish Roman society, Alban was a compliment. It was a golden vintage, with a local terroir, a liquor of price that the best people would bring out for visitors. Slurping this, Curvidius Fulvianus would feel he had status among us, perhaps not honour, but respect. A two-pepper sauce on the entrée would reinforce his satisfaction.

Of course, if Curvidius spotted that Tullius had instructed the drinks-mixer to apply the notorious rule of ‘eight parts water, one part wine’, he might rethink. Still, he would have heard from fellow-traders that Tullius Icilius fell short of miserly yet was always careful. ‘Careful’, in business, is a synonym for mean as stink.

Watching the scene as Tiberius had urged me to, I saw Curvidius drink whatever was in his goblet. He never stretched out his arm impatiently for a refill, but he knew how to catch a slave’s eye unobtrusively. Staff served him willingly; his behaviour had not caused them to look the other way, as servers in their own house will do if slighted by a boorish guest.

Tullius was barely bothering to drink. He would wait until Curvidius left, and possibly even us, his nearest relatives. Then, with his feet up in battered slippers, he would apply the

other ancient adage: ‘Eight parts wine for me, forget the water.’ Finally on his own, he would enjoy himself.

My husband was refusing top-ups, though not from prudery. Tiberius preferred to feel sober among strangers. He liked to choose his company. Of course, if he felt comfortable, he could knock it back. Six months ago, he had managed to return alive from a stupendous bar-crawl with my father – he endured that test because Falco would not release rights in one of his daughters to a man he viewed as a wimp.

Wimpiness was not an issue. Tiberius had been pre-vetted as husband material by me, a private investigator who specialised in checking bridegrooms for nervous families. I was a widow, close to thirty and realistic. But my skills were irrelevant: Pa had enjoyed the power, putting his hopeful son-in-law through a night of stress.

On the evening at his uncle’s, Tiberius viewed Curvidius Fulvianus as work, so he called the Alban ‘very drinkable’ yet discreetly held off. As for me, I practised the informer’s trick. Falco had taught me this. I kept my nose in my bronze wine cup, gave a minute head-shake when anyone approached offering more, applied a thoughtful exterior and quietly absorbed the scene.

Uncle Tullius was expecting sharp conversation from me; he looked suspicious at my silence. Fulvianus never noticed. He must believe that the Icilius family had snared a dutiful matron who would enhance her male relatives: wear a lot of jewellery, eat a few prawn balls, look admiring when a man spoke, and otherwise behave just as authors of the duller kind tell us is traditional for Roman

women.

‘Cobnuts!’ That would be my mother, Helena Justina. She had picked up the expletive from Father, but the indignation is hers. She encouraged me to shake up dinners with controversial remarks, stopping short only of anything that might cause my husband to be executed. ‘Unless,’ murmurs Mama, ‘he has done something really irritating. Then you may as well let rip.’

Watching the men as they danced their dance about the villa sale, I thought Curvidius was too bland. He would not agitate a beetle. On one of my tetchy days, his sheer dullness would have riled me. No one should choose to be unremarkable. Would I buy a house from him? No, Legate.

Of course, it would be unfair to dismiss our uncle’s vendor for keeping his own counsel. But even though the deal was already signed and stamped with their manly seal rings, I felt this fellow needed to convince us that whatever he had shifted onto Tullius was honest real estate. So far, I remained sceptical.

Tullius mostly sat out the discussion. His nephew acted as his agent. It must have been clear from his questions that if our workmen uncovered any structural flaws, my husband would take it up, even post-contract. He knew enough about buildings to judge whether failures of maintenance were responsible for problems, rather than Vesuvius. Fulvianus brushed this aside almost lazily. Like anyone Tullius knew, he had rich experience with deals. He reckoned he could negotiate his way past a tricky nephew: ‘You know, we had an earthquake a few years before the eruption.’

Oh, good try, honourable vendor!

one. Recovery had been slow afterwards, according to my sources. Rebuilds had hardly got going when the fatal disaster struck. I guess repair firms had been much in demand and they were able to charge as much as they wanted.’

‘Fair point,’ weighed in Tullius. Uncle and nephew nodded at each other, then Tullius reapplied himself to the dessert comport. He looked surprised there were so few honeyed dates left; he could not have spotted me grazing. No platter is safe near a woman who is pretending to be a traditional matron. You cannot pick your nose (Mother again), so you have to pick at the sweetmeats.

Tiberius beat his uncle to the last apricot. ‘I concede there could be earlier damage from seismic waves . . .’ a thoughtful chew ‘. . . but when Vesuvius began its act, of course there were more earthquakes.’ Everyone looked impressed. Old Grey Eyes must have drunk more of the Alban than I had realised, from the way he settled in to lecture us. ‘Buildings are more easily harmed by horizontal motion than vertical. Low-frequency vibrations are the worst; the ground floor crumbles, then the upper storeys pancake down on top.We assume this doesn’t apply to your property, Sextus Curvidius, my friend. But structures can be harbouring serious cracks that are a bugger to correct.’ Tiberius certainly did initial research. He smiled, affable as a homing-in mosquito. ‘I learned that from my grandfather. “Bugger to correct” is a technical term, he said!’ Then he slid in: ‘I assume you had had any earthquake damage assessed and repaired?’

Tullius began to look anxious. Clearly he had never obtained a schedule of defects before signing the purchase agreement.

Fulvianus waved it away. ‘Not my responsibility. My brother was still alive.’

This introduced the brother neatly. Deflected from potential defects, Tiberius moved on to the issue of human remains. He reprised how Uncle Tullius had told him Fulvianus wished to have his sibling identified, if possible. How would we identify the brother? If our labourers were to meet any skeleton face to face, one grinning skull would look much like another.

The reply was unhelpful. Fulvianus said he had not been to Campania for many years prior to the eruption, nor had he returned there since. Before that, he and his brother had never got on. No reason was given. Tiberius shot me a glance, with the option to ask questions. I let it pass. Arguing families are the norm in my work, and if we needed to know details of a split, I might prefer to ask other people, neutral witnesses.

‘We kept in touch when we had to,’ Fulvianus conceded. ‘Intolerable swine. I sent him a gift for his sixty-fifth birthday, never had an acknowledgement, not one word of thanks.’

‘What was the gift?’ I asked, pondering whether their courier had pinched it, as would be usual. ‘In case we find it?’

‘Bloody great vase. Some Greek with a beard, putting his spear in. Cost me a packet.’

Privately, I wondered if the recipient had felt this choice of gift was a hint: had his brother sent him a funeral

urn, naughtily suggesting that sixty-five would be his last anniversary?

Tiberius double-checked: ‘Even though you were at odds, you want to give your brother’s soul a proper send-off?’

Bland as ever, the survivor answered, ‘One has one’s duties to family.’

The brother had been Publius Curvidius Fulvius Primus. He was a childless widower. As his final cognomen suggested, Primus was the first-born. Beyond that there was little to help with identification. As far as Fulvianus knew or could recall, Primus had possessed no physical peculiarities, nor had he ever experienced any broken bones. (Tiberius again caught my eye; that would have made our task too easy!) The two had been similar in height, which was a start, but colouring and other characteristics would not have survived their ten-year interment in volcanic ash. ‘He let himself go. He got heavy, I believe.’ Fulvianus, a trim man, seemed to enjoy this sneer.

I bestirred myself to contribute professionally: might a signet ring or other jewellery have been worn? Fulvianus raised his eyebrows at the way I joined in, but allowed himself to reply that he could not even remember what his brother’s seal had been; his own secretary would have it in family records, so he would find out.

Originally the family came from Campania: to be precise, Salernum on the way to Paestum. The villa at Stabiae had been a family home, though they owned others. Fulvianus had moved to Rome many years ago to pursue business interests at the heart of things, though he still had a small clutch of relatives down south: distant

connections, he implied. Once it had been determined that Primus was missing and must have perished, Fulvianus stepped up as head of the family, assuming ownership of the homestead at Stabiae. Tullius had now acquired everything within the curtilage, with an understanding that outdoor amenities that might once have existed were sadly all defunct. Behind the villa there had been gardens, a vineyard and an orchard with olive trees. They were buried by the volcano. ‘Nothing that grew has survived, but I understand there are still outbuildings. You can stable your mules.’

The floor plan was brought out. Tiberius flipped the crackling skin across the serving table, but when we asked Fulvianus how rooms had been used by his family, remembrance seemed to upset him. Without pressing, Tiberius made quick descriptive notes in ink, then re-rolled the plan to take home.

We did not ask, and were not given, legal information. Curvidius Fulvianus behaved as an owner with good title; Tullius had accepted that in good faith. If Primus had ever made a will, it had vanished, like so many documents that belonged to people killed in the eruption. Fulvianus had had to guess what his brother had wanted.

It was the same for many. Family and business records perished. Only by chance were documents ever found later, usually dropped in ditches by fleeing refugees, when carrying heavy record-chests through the smog and debris became impossible. Even if old scrolls were dug out now, they would be irrecoverably damaged.

I had done research of my own kind before we came tonight. I went to the Basilica Julia to ask legal questions. I learned that attempts had been made to smooth out problem situations when

landowners around Vesuvius had obviously died. Often there were no survivors to inherit. In that situation a commission appointed by the Emperor had made compulsory acquisitions. If a challenger ever did raise objections, I was told that courts had tried to find speedy, non-controversial ways to a settlement.

‘Really? Didn’t it lead to chancers bringing fake claims?’

My contact Honorius was an old associate of Father’s, mired in Falco’s cynicism. He agreed. However, as an earnest practising lawyer, he claimed that taking advantage of the catastrophe fraudulently had been viewed by judges – ‘well, most judges’ – as an improper use of litigation. So great was the national trauma that even those who worked in the law had reacted by being honest and helpful on land reassignment. I tried to believe that.

Conscious of libel, Honorius declined to name any property raiders – though it was clear he could have done.

‘Immoral scams!’ I had grumbled at him. In reply, Honorius told me the legal definition of a scam was ‘an opportunity’.

I did not report this at dinner. If Tullius and Curvidius Fulvianus were mutually happy about their sale, nobody needed to cause them anxiety. To do business on a handshake was normal procedure in their world; for landed property a contract would be needed, but their spoken agreement would have been the key formality. Even Tiberius was only going to quibble if the house was really so fragile it fell down.

The servers came to carry out the table and dishes. Fulvianus took his leave.

‘You’ll be off, then!’ exclaimed Uncle Tullius, keen to be rid of us.

Tiberius and I stayed put. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...