- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

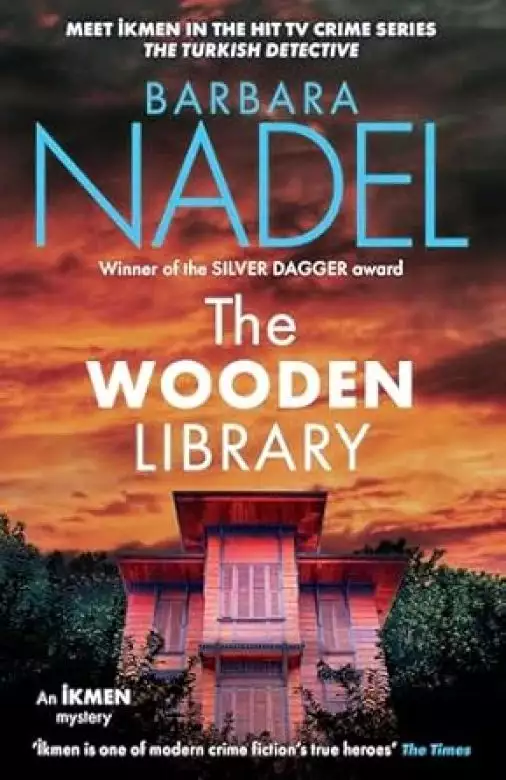

The twenty-seventh mystery featuring Çetin İkmen and Mehmet Suleyman, stars of BBC Two's gripping crime drama series The Turkish Detective, available to watch on BBC iPlayer.

Praise for Barbara Nadel's İkmen mysteries:

'Complex and beguiling: a Turkish delight' Mick Herron

'İkmen is one of modern crime fiction's true heroes, complex yet likeable, and the city he inhabits - Istanbul - is just as fascinating' The Times

'Barbara Nadel's distinctive Istanbul-set Inspector İkmen thrillers combine brightly coloured scene setting with deliciously tortuous plots' Guardian

Release date: May 8, 2025

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Wooden Library

Barbara Nadel

June 2023

‘Mehmet!’ Çetin İkmen smiled into his phone and added, ‘How is Romania?’

‘Strange,’ his friend replied. ‘You’d love it.’

Ex-inspector of police Çetin İkmen brushed a small avalanche of breakfast breadcrumbs off his shirt and lit a cigarette.

‘Anywhere apparently infested with vampires and werewolves is never going to be dull,’ he said. ‘Also, my son Orhan tells me that their cars are very good these days.’

‘Ah, the Dacia,’ Mehmet Süleyman said. ‘Yes, tough vehicles. My wife’s brother has one, and the way he drives, it needs to be.’

Inspector Mehmet Süleyman of the İstanbul Police Department was on holiday in a village just outside Bucharest. Many years before, the brother of his Roma wife Gonca had married a Romanian gypsy, and now the Süleymans were visiting that family for the first time.

‘So does Cengiz Şekeroğlu have a large family?’ İkmen asked.

‘Oh yes, although to be honest with you, I don’t know how many of the children who run in and out of this house day and night are actually his. This village is, I think, almost a hundred per cent Roma, with the exception of one or two Romanian families and me.’

İkmen laughed.

‘All probably related and most of the adults involved, like Cengiz, in gypsy bands and dance troupes,’ Süleyman went on. ‘But Çetin, look I’ll tell you everything about it when I get home. I’ve called to ask you a favour, albeit a paid one . . .’

‘I like the sound of that!’ İkmen said.

‘Do feel free to say no,’ Süleyman continued. ‘I say this because this favour involves contact with my family.’

Mehmet Süleyman came from an old Ottoman family distantly related to the sultans of Türkiye. Partly as a result of this, some of his relations – mainly his mother – could be unpleasantly snobbish, particularly when it came to Mehmet’s Romany wife. İkmen, who didn’t suffer fools or snobs lightly, found his friend’s mother particularly hard to take.

‘Your mother?’ he asked.

‘No. My father’s cousin, Nurettin.’

‘I don’t think I’ve ever met him,’ İkmen said.

‘No, you wouldn’t have.’

‘Why?’

He heard Mehmet sigh. ‘Because my father always kept us away from that side of the family. Nurettin is my father’s cousin. His father, my great-uncle, Haidar, died before I was born. My father used to say they were utterly profligate. Apparently Haidar was always trying to borrow money from my father for one mad scheme or other.’

İkmen cleared his throat.

‘Ridiculous, no?’ Süleyman said.

Mehmet’s late father had been well known across the city for always being broke and often in debt.

‘Anyway, Nurettin made contact.’ Süleyman sighed.

‘How did he get your number?’ İkmen asked.

‘From my mother, who else? Of course she promised him that I’d help him. Family solidarity. Utter nonsense! Anyway,’ he continued, ‘it seems that Nurettin has now come into some money, which means he has managed to buy back a piece of property his side of the family had to sell off decades ago. Long story short, it is a wooden library my ancestor Şehzade Selahattin Efendi used to house his massive book collection back in the 1870s. And unbelievable as it sounds, Nurettin tells me that the books are still in situ.’

İkmen said, ‘Well I suppose if they’ve been kept out of the light in a temperature-controlled—’

‘They are apparently just as Şehzade Selahattin Efendi left them,’ Süleyman said.

‘Oh . . .’

‘And Nurettin wants to catalogue them,’ he added. ‘Which was why he called me while I am on holiday . . .’

‘To help him?’

‘No, to speak to you about helping him,’ Süleyman said.

‘Me?’

‘Everybody even remotely connected to me knows that I used to work for and alongside you, Çetin. Like it or not, you are the most famous and trusted police officer in the country.’

‘Hasn’t exactly made me rich . . .’

‘Because you’ve never wanted to be rich,’ his friend said. ‘You could be a millionaire now if you’d kissed the hands offering you bribes instead of imprisoning them. You may be poor, but you’re loved and trusted and clever, and don’t try to deny it. Nurettin wants you to help him catalogue what may just be piles of dust but that also may be some very interesting books. He’s said he’ll pay you and I’ve told him that if he doesn’t, he’ll have me to deal with. Now what do you say, are you in or out? He’s given me his number to pass on to you, and because he’s an entitled aristocrat, he’ll expect an answer today.’

Burcu Tandoğan had it all – looks, money, an apartment overlooking the Bosphorus and an adoring fan base. Ever since she’d appeared on daytime TV magazine programme, The Kaya Show, she’d been a sensation. So young and yet so gifted. Her predictions, particularly those related to the progress of the COVID-19 virus, had made her Türkiye’s foremost spirit medium. Expertly treading the thin line that existed between a country that was governed by a religiously conservative party and individuals desperate for answers about their uncertain future, Burcu was loved by avowed secularists, some ministers of religion and the armed forces.

She sat down on the floor. It was dusty and uneven, and annoyingly, she noticed that her thin golden gown had snagged on some splinters. She could have it repaired, but it was easier to just buy a new dress. Pushing her long white-blonde hair over her shoulders, she closed her eyes and entered the first phase of her trance.

Her task was to make contact with Byzantine Empress Zoë Porphyrogenita. Born in 978, Zoë was said to have been beautiful, clever and a witch. One school of thought had her down as a murderess too, but that was of no interest to Burcu, or rather to Burcu’s client. Something that had belonged to Zoë was in this old building hidden away behind a shabby fifties apartment block in Taksim. An İstanbullu born and bred, Burcu had never seen this place so close to the heart of İstanbul in her life. The quiet in which it appeared to exist was a revelation.

The smoke she always saw behind her closed eyes when she entered trance appeared and then gradually turned a deep shade of purple. This was a good sign. Purple had been the regal colour of the imperial Byzantine family, and so Burcu sank into it as she began to intone Zoë’s name, swaying backwards and forwards in time to the syllables of the word.

Pictures appeared – of glittering mosaics she recognised from inside the dome of the Aya Sofya, of an artist’s impression she had meditated upon of the Byzantine Hippodrome. Jewels dripping from crowns of soft yellow gold and the smooth face of a white-skinned woman . . .

No. No, a white-skinned man. No, blue. Had she allowed her concentration to wander? Had she been distracted? She visualised the crown again, this time placing a beautiful face with ruby-red lips beneath it, only to find it changed once more. The man . . . blue . . . features a blur . . . eyes open . . .

Dead.

Fighting her way out of the trance, Burcu retched, gagged and then screamed. As she tried to jump to her feet, shaking now, her golden gown caught on even bigger splinters, which ripped the hem of the skirt almost clean away.

There were three of them in the office. There were usually two, which meant that in this atmosphere of extreme humidity and blistering heat, and even with two fans going on maximum, none of them could speak. Mehmet Süleyman was away for two weeks now and Inspector Kerim Gürsel wondered how he was going to cope.

Back in February, Süleyman’s sergeant, Ömer Mungun, had been shot in the right shoulder by someone, as yet unidentified, who was believed to be working on behalf of the Italian Cosa Nostra. Now it was June, and Ömer was still not fit enough to return to duty – apart from anything else he could not hold, much less fire, his service revolver. His temporary replacement, a very young officer called Timür Eczacıbaşı, appeared to be efficient enough when going about his duties for Süleyman. But seconded to Kerim in Mehmet’s absence, he got in the way.

Kerim had been partnered with his sergeant, Eylul Yavaş, for a long time. They were very different. She was a single, religious, covered woman from a wealthy family while Kerim was a secular man who lived with his wife and daughter in a down-at-heel part of the city called Tarlabaşı. He was also homosexual, although that was an aspect of his life he kept to himself. Among the very few people who knew his secret were Mehmet Süleyman and Çetin İkmen, although unknown to him, Eylul knew too. Fiercely loyal to her boss, she looked out for him, just as he always cared for and supported her. They were a tight team with no room for anyone else.

Unable to think of anything more productive to give the young man to do, Kerim asked him to go out and buy them all drinks. A new café had recently opened opposite headquarters, and he’d heard they served iced coffees.

‘Get one each for Sergeant Yavaş and myself, and whatever you want,’ he said as he pressed some banknotes into the young man’s hands.

‘Thank you, sir,’ Timür said. But he didn’t go immediately; instead he bit his lip and then added, ‘Sir, about this missing man . . .’

‘What missing man?’

‘Şenol Ulusoy. His wife reported him missing this morning. Comes from Şişli, retired banker.’

Kerim vaguely recalled that a man was apparently missing. Turning to Eylul, who lived in Şişli, he said, ‘Ulusoy mean anything to you, Sergeant?’

‘No.’

Then looking up at Timür he said, ‘How long’s he been missing?’

‘Two days, sir,’ Timür said. ‘He went out in the evening to have a walk by the Bosphorus and never came home.’

‘Maybe he melted,’ Kerim said. Then, seeing the look of horror on the young man’s face, he added, ‘I mean maybe he collapsed. If he’s retired, he might be quite old. Have you checked the hospitals?’

‘Yes, sir.’

He sighed. He didn’t want to go out in the furnace that was outside. But . . .

‘Give the wife a call,’ he said. ‘Make an appointment to go and see her. Maybe try to find out sensitively whether the old man has memory problems.’

‘OK.’

Timür made to go back to his desk, but Kerim saw the look of panic on Eylul’s face and said, ‘But get the drinks first.’

In spite of not being able to speak Romanian or understand the local Romany dialect, Gonca Süleyman was being introduced to everyone in her brother’s village. With Cengiz as her translator, she was transported from house to house with great ceremony. Everyone wanted the world-famous artist and renowned witch to read their cards in return for mountains of food and liberal amounts of the local plum brandy, țuică. Most of the latter was moonshine made by villagers whose stills, it was said, peppered the nearby Boldu-Crețeasca forest.

There was also what Gonca described as a ‘magical’ pond in the forest where witches performed their rituals prior to the midsummer festival of Sânziene. In part it was the Sânziene festival that had brought Gonca and her husband to Romania. Her brother made his living working as a violinist in a Romany band, and Sânziene was one of his busiest times of the year. Travelling in and around the forest to play at celebrations, Cengiz wanted to show his older sister what a success he’d made of his life in Romania, as well as introducing her to his family.

With the festival only five days away, everyone was getting ready – washing their best clothes, preparing bottles to be used for the healing potions they would make when they collected the yellow Sânziene flowers on Midsummer’s Day, creating celebratory flower garlands and wreaths. Nobody had much time for a solitary Turk, even if he was married to Gonca. Language was of course a huge barrier, but no one offered to translate for Mehmet, and so he spent a lot of time on his own, walking around the edge of the forest. The one thing Cengiz had told him about Boldu-Crețeasca was that he should not venture too far inside in case he met a bear. And although Mehmet was old enough to remember when the İstanbul Roma paraded dancing bears on the streets of the city, those poor things were quite different from wild bears.

Sitting down on a grassy hummock behind the village, Mehmet Süleyman looked into the darkness of the forest and thought about his recent conversation with his father’s cousin, Nurettin. He’d heard nothing from that branch of his family for decades and yet Nurettin had greeted him with enormous warmth and bonhomie.

‘Mehmet, my dear cousin!’ he’d declared with wild enthusiasm when Süleyman had answered his phone. ‘How are you? Where are you? I heard you married a Roma. You must tell me everything!’

And while not knowing Nurettin at all really, Mehmet played along until he discovered what his cousin actually wanted. He knew he wanted something, firstly because otherwise why would he call him out of the blue, and secondly because his father, Muhammed Süleyman, had always described that branch of the family as ‘a dishonest rabble of unforgiving freeloaders’. And although Mehmet didn’t know exactly why his father had said this, he did know that there were dark rumours about them that included gambling, bankruptcy and unnamed ‘unnatural acts’.

However, when Nurettin told him he was calling to, hopefully, enlist the help of Çetin İkmen with the cataloguing of his great-great-grandfather’s library, he did have to admit that his interest was piqued. Şehzade Selahattin Süleyman had been a highly educated man who back in the nineteenth century was said to have the most comprehensive library in the Ottoman Empire. A diplomat, at one time First Secretary to the Embassy of the Ottoman Empire in London, a lot of his books were written in English, which was why Nurettin wanted to employ the Anglophone İkmen.

‘I’m fine with French, but I was never really interested in English,’ he had told Mehmet. ‘I found it ugly, like German.’

It was hardly the investigative work İkmen usually did, but it would, Süleyman felt, provide his old mentor with what could be an interesting distraction. He needed that at the present time. Three years after the death of his wife in 2016, İkmen had started a relationship with Peri, the older sister of Mehmet’s sergeant, Ömer Mungun. She made him happy until, in the wake of her brother’s gunshot injury back in March, she’d told İkmen that she needed a ‘break’. Why, Mehmet didn’t know, but İkmen without work or Peri was not a happy man. Hopefully Nurettin would keep him occupied and pay him fairly for his time – although the latter aspect was in no way guaranteed.

It was said that Nurettin’s family had lost Şehzade Selahattin’s library sometime back in the 1950s – probably due to debt, although no one really knew. Maybe with İkmen involved, the rest of the Süleyman family would learn something about that and about how Nurettin had apparently taken ownership of the building once again.

He both looked and sounded like Mehmet’s late father, Şehzade Muhammed Efendi. Tall, slim and handsome, Nurettin Süleyman was dressed immaculately in a grey suit with a white shirt and opulent purple tie. Unlike İkmen, who looked like a homeless man who’d just been in a rain shower, Nurettin Süleyman was a being entirely without sweat. Leaning lightly on his silver-topped cane, he met İkmen outside the wall at the back of the Şehzade Selahattin Library, just as the light from the setting sun made his thick black and grey hair look like mercury.

‘I can’t tell you how pleased I am you agreed to meet me,’ he said as he held a perfumed hand out to İkmen. ‘You know my whole family are so grateful for the way in which you mentored Mehmet when he was a young man. You are the reason why he’s so successful now.’

İkmen took the man’s hand in one of his own sweaty paws and shook it. He knew that Nurettin was flattering him and just smiled.

‘Now, as we discussed on the phone, the job I have for you may or may not be vast,’ Nurettin said. ‘I have no idea, as yet, about the condition of the books across the entire collection. When I was given the keys two days ago, I did have a peek into the entrance hall, where it seemed to me all was well. But then again, once touched, the books may very well crumble to dust in our hands. Until this most recent visit I had not seen the inside of the library since the 1950s.’

İkmen frowned. ‘Forgive me, but if the books are so delicate and possibly valuable, wouldn’t it be better for you to engage a proper historian. Such a person will have access to restorers . . .’

‘This library was taken away from my family sixty years ago, Çetin Bey,’ Nurettin said, rather pompously, İkmen thought, ‘and so I am not about to allow it to fall into unknown hands again, not even if those other hands belong to the state. Any risk I am taking with these books is mine to take and mine alone. If you find that you cannot condone my desire to do with my property what I will, then please do tell me now so that I may dispense with your services.’

His approach was so high handed that İkmen was tempted to tell Nurettin to go to hell, but he also knew that he was doing this as a favour to Mehmet, who wanted to find out more about what was known as the Wooden Library.

‘It’s fine,’ he said. ‘I just wanted to raise the issue . . .’

‘Well now you have, and I have answered you,’ Nurettin said as he pushed open a wooden door and, urging İkmen to follow him, walked into an idyllic, if overgrown, garden. İkmen, who had always prided himself on his İstanbul knowledge, had had no idea this place existed. It was just behind Taksim Square, the heart of the modern city of İstanbul, yet no traffic noise seemed to penetrate the thick stone walls surrounding the garden.

‘It was built in 1873 to house my great-great-grandfather Şehzade Selahattin Efendi’s enormous book collection,’ Nurettin said as he called İkmen’s attention to a sagging and time-scarred building almost obscured by what looked like a small olive grove. Hardly, to İkmen’s way of thinking, a palace, the library was more like one of the smaller ornate Ottoman kiosks one saw out on the Princes’ Islands. There was a slight German influence characterised by numerous heart-shaped carvings on the walls – like the gingerbread house in the Grimms’ fairy tale. He contrasted the little building with the low-rise 1950s apartment block at the top of the garden – all discoloured concrete festooned with poorly attached utility cables – where Nurettin had been brought up and where he still lived. The Ottomans, for all their faults, had known how to make attractive buildings.

‘I’ve no idea how many of the books are written in English,’ Nurettin said. ‘But Şehzade Selahattin did live in England for at least ten years, during which time it is thought he shipped thousands of books home.’ He smiled. ‘Provided the books are intact, I think you may have a job for quite some time, Çetin Bey.’

‘Indeed. But what about the other books?’ İkmen asked. ‘I mean, I assume a large number of them are written in Ottoman Turkish.’

Prior to the establishment of Atatürk’s Turkish Republic in 1923, the Ottomans wrote their language in Arabic script as opposed to the Roman alphabet used today. In practical terms this meant that often old Turkish texts had to be translated.

‘Oh, I was taught to read and write Ottoman Turkish as a child,’ Nurettin said. ‘So that task I have allocated to myself, ditto books written in French.’

Like Mehmet, Nurettin Süleyman had attended the prestigious Galatasaray Lisesi – Türkiye’s foremost boys’ school since Ottoman times. This was where princes, kings and captains of industry went, and many classes were conducted in French.

As he unlocked the front door of the library, Nurettin asked, ‘Çetin Bey, can you speak Greek at all?’

‘I can decipher the alphabet, but that’s about it,’ İkmen said. ‘You think that some of the books might be written in Greek?’

‘Possibly,’ Nurettin said. ‘Just a thought.’

He pushed the door open to reveal a large circular hallway from which rose a staircase leading to a gallery that ran around the top of this central hall. Closed doors at both ground and first-floor level were inlaid with coloured wood marquetry depicting things İkmen could not make out. But then it was not the doors that were of interest to him. Vast, if sagging, bookshelves failed to hold onto the almost unimaginable number of volumes they had been built to support, meaning that great towers of novels, map books, academic tomes and who knew what else were piled up on floors that also creaked and bowed beneath their weight. Even the stairs were littered with volumes, and as the last rays of the setting sun penetrated the small windows in the building’s delicate onion-domed roof, İkmen could see that the air around him, around everything, was thick with dust so dense it was almost edible.

He was fairly sure that his friend Mehmet had not realised the scale of Nurettin’s problem, but he said nothing. He wanted something to do, and this job had the potential to be very interesting. Who knew, maybe he’d find a Charles Dickens first edition. If, of course, he could bear the heat. After a rainy spring, İstanbul had been hit by summer temperatures so high there had been times when it had made him feel sick. And old wooden places like the library were heat magnets.

As if reading his mind, Nurettin Süleyman said, ‘As you can imagine, there’s no water here, but we can of course bring that from my kitchen.’

İkmen looked back through the open front door at the shabby apartment building.

‘Nurettin Bey, I can’t see any sort of fence between your property and this,’ he said. ‘Has it always been like this?’

‘No.’ Nurettin turned away slightly. ‘The people who purchased the Wooden Library from us put a fence up in the 1950s. I had it taken down as soon as we took possession. Unnecessary now, and it’s nice for my aunt to be able to finally walk in the garden as she did many years ago.’

‘Your aunt?’

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘She lives in the apartment above mine. She’s very old now. I doubt she’ll trouble you.’

İkmen turned back to the books. For the first time, he noticed something glittering in the middle of the hall.

He walked over to it. ‘What’s this?’

It was a piece of gold-coloured material, dotted with gold sequins. It looked as if it had come from a woman’s skirt.

‘That?’ Nurettin shook his head. ‘I don’t know.’ Then he said, ‘Ah, but of course I brought my aunt in here yesterday. She’s old and fond of wearing floor-length skirts. Yes, now that I recall, she did have a bit of a mishap.’

A bit of a mishap? It was more than that. But İkmen said nothing and just put the material back down on the floor. Mehmet’s family, he had learned over his many years of association with them, were not like other people.

Şenol Ulusoy and his wife Elif lived in a large apartment on Papa Roncalli Sokak in an area of upscale Şişli called Pangaltı. Famous for its prestigious convent school, Notre Dame de Sion, Pangaltı was the sort of place where one would expect to find a retired banker. Generally quiet, it was very close to Taksim Square and was dotted with patisseries and cafés.

Kerim Gürsel hadn’t wanted to move far when Mehmet Süleyman’s deputy, Sergeant Timür Eczacıbaşı, told him he’d made an appointment to see the wife of the missing Şenol Ulusoy. In fact he’d been almost asleep. His own sergeant, Eylul Yavaş, had been so badly affected by the heatwave that in spite of drinking a huge, iced latte and incessantly pouring cold water down her throat, she had eventually been overcome by sickness and had gone home. This left Kerim and Timür, who were now interviewing a smart woman in her seventies at her mercifully air-conditioned apartment.

Still sweating slightly in spite of the air con, Kerim asked Elif Hanım about her husband.

‘Şenol is seventy-five,’ she said. ‘Retired, as you know, and in reasonable health – well, he was before this heatwave. He doesn’t deal well with it. He often goes for long walks, usually beside the Bosphorus, but he’s never done so at night before. He went out at about eight, citing the awful heat as the reason he had left it so late.’

‘Makes sense,’ Kerim said.

‘Well, that’s what I thought,’ she said. ‘But then as time went on and he still wasn’t home . . . I called Rauf Bey, but he said that Şenol hadn’t been there.’

‘Where?’

A maid brought them all tea, after which Elif Hanım continued. ‘Oh, of course you don’t know. My husband’s father is dying. Şenol’s brothers, Rauf and Kemal, spend a lot of time with him, as does my husband.’

‘At which hospital is this, hanım?’ Kerim asked.

‘Oh, Rıfat Paşa is not in hospital,’ she said. ‘He is under medical supervision at his home.’

Timür looked a little bewildered. It was generally only the poor who died at home these days. But Kerim, with his much greater life experience, knew that the very rich sometimes did that too.

‘So where does your father-in-law live, Elif Hanım?’ he asked.

‘He has a house in Arnavutköy,’ she said. Then she shook her head. ‘We, his family, have put in round-the-clock nursing care and doctor’s visits. He fell into a coma five days ago. I thought that my husband may have been to see him after his walk. The three sons have arranged it so that someone is always with him. Of course, sometimes that’s impossible, though Şenol and Rauf spend as much time with him as they can.’

They didn’t want their father to die alone. Kerim found that touching. But he found Elif Hanım’s use of the title ‘paşa’ in relation to her father-in-law strange. The old Ottoman title referred to a man of note, often a member of the imperial family or a general in the army. People still used the title ‘efendi’ sometimes, but not ‘paşa’. It was odd – as was Elif Hanım’s very obvious coldness.

‘And the third brother?’ Timür asked.

‘Oh, Kemal, I don’t know,’ she said. ‘My husband and his youngest brother haven’t talked for many years . . .’

‘And yet you told us the three of them attend your father-in-law at all times.’

‘Rauf Bey acts as intermediary between Şenol and Kemal. I think they try not to be present at the same time as each other. But anyway, my husband was not at his father’s house.’

‘Was your husband upset when he left here the night before last?’ Kerim asked.

‘No. Well, no more than usual,’ she said. ‘His father is dying and so . . .’ She shrugged.

‘Understood.’

‘Has your husband ever gone off for extended periods of time on his own before?’ Timür asked.

‘No. As I said, he likes to go for long walks, but he always comes home.’

‘Do you have children, Elif Hanım?’ Kerim asked.

‘Yes, a son, Aslan. He lives with his family in İzmir. Şenol Bey definitely isn’t there. In fact Aslan told me just this morning that if his father hasn’t appeared by tonight, he’s going to fly up here overnight to be with me.’ She shook her head. ‘It’s so out of character.’

‘Your husband hasn’t been ill of late?’

She looked at the younger man. ‘No. Apart from the heat affecting him badly. Of course he has the usual aches and pains associated with old age – some arthritis in his knees, high cholesterol. But it’s all under control. Naturally he’s upset about his father, and I have to admit that he has gone into himself rather. As Rıfat Paşa’s principal heir, Şenol Bey has been obliged to take over his business, which at seventy-five is a lot for him.’

‘What is Rıfat Paşa’s business?’ Kerim asked.

‘Property development,’ she said. ‘He owns land and buildings all over the city, some of which he sells, some he rents out. Until this last illness, my father-in-law, who is now ninety-six, controlled everything himself. Şenol has been under a lot of stress, I do have to say.’

When they left the apartment, Kerim stopped outside to smoke in the shade of a balcony before getting back into his car. He looked at Timür. ‘So?’

‘So?’

‘What did you make of Elif Hanım and her story?’

‘Very sad,’ Timür said. ‘It must be difficult for someone of Şenol Ulusoy’s age to take over what sounds like quite a property empire, while also caring for his dying father. It’s the sort of thing that could easily break a person.’

Kerim nodded. ‘Especially with one of his brothers apparently unable to be in the same room with him.’

‘I thought I might ask Elif Hanım about that,’ Timür said. ‘But then I thought better of it.’

‘Good.’

‘Good? I’m wondering now whether I should have,’ the young man said.

‘If Şenol Bey doesn’t reappear by tomorrow, we will ask,’ Kerim told him. ‘But not yet. If he strolls back into his apartment this evening, we won’t need to know. Family feuds are often ridiculous and complicated, and I try to steer clear of them whenever I can.’

When the sun finally deigned to set that evening, Çetin İkmen left home to go to his favourite bar, the Mozaik, mere steps from the entrance to his apartment building. The staff knew İkmen and his cat, who always accompanied the ex-policeman whenever he went there. And so as he wa

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...