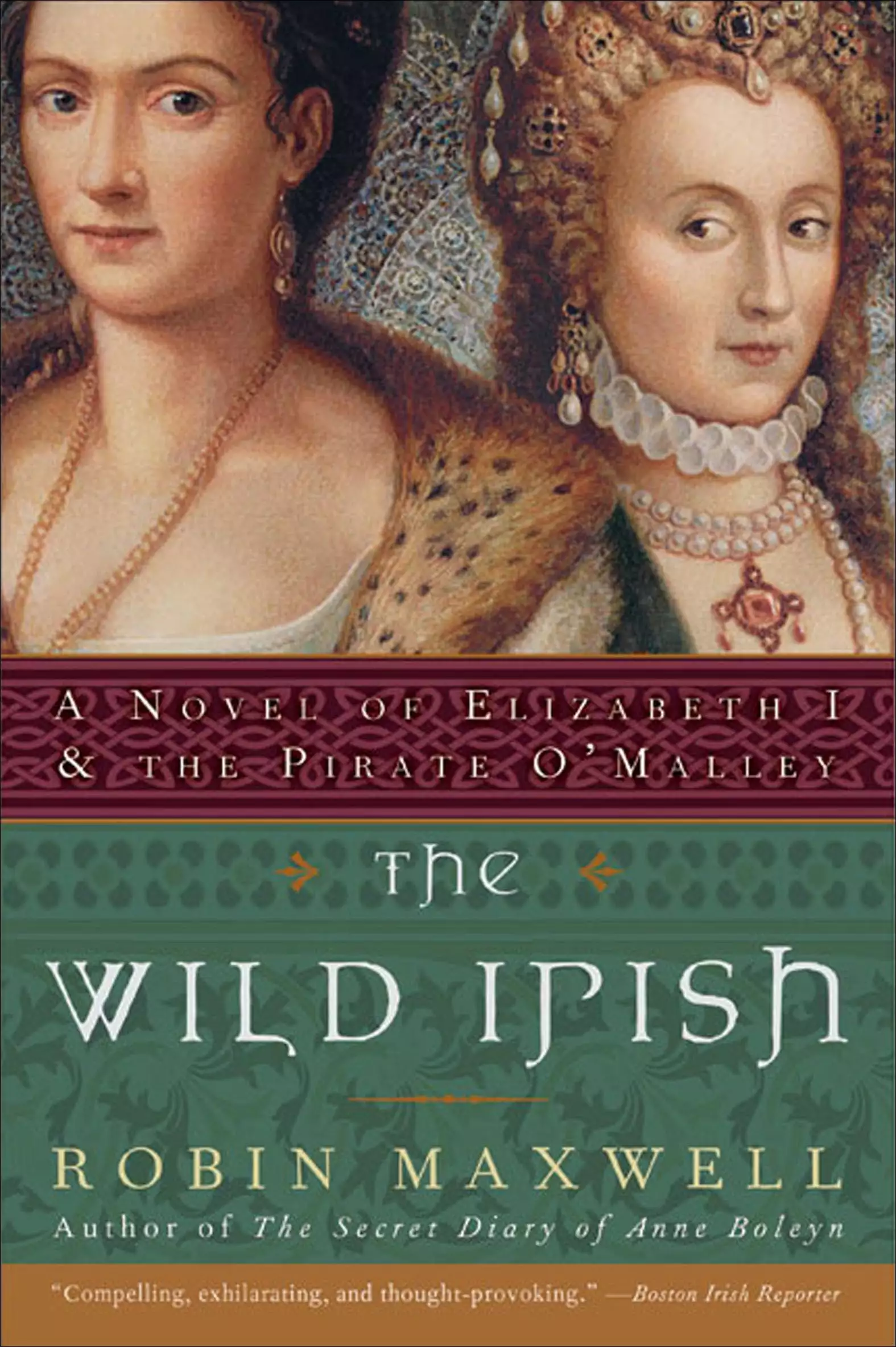

The Wild Irish: A Novel of Elizabeth I and the Pirate O'Malley

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Two female titans -- perfectly matched in guts, guile, and political genius.

Elizabeth, queen of England, has taken on the mighty Spanish Armada and, in a stunning sea battle, vanquished it. But her troubles are far from over. Just across the western channel, her colony Ireland is embroiled in seething rebellion, with the island's fierce, untamed clan chieftains and their "wild Irish" followers refusing to bow to their English oppressors.

Grace O'Malley -- notorious pirate, gunrunner, and "Mother of the Irish Rebellion" -- is at the heart of the conflict. For years, she has fought against the English stranglehold on her beloved country. At the height of the uprising Grace takes an outrageous risk, sailing up the Thames to London for a face-to-face showdown with her nemesis, the queen of England.

In this "enthralling historical fiction" (Publishers Weekly), Robin Maxwell masterfully brings to life these strong and pugnacious women in order to tell the little-known but crucial saga of Elizabeth's Irish war.

Release date: October 13, 2009

Publisher: Avon

Print pages: 402

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Wild Irish: A Novel of Elizabeth I and the Pirate O'Malley

Robin Maxwell

THE SUN WAS WARM on her face and she wondered, Where were the mists? London was perpetually shrouded in fog, was gray and dreary. And it stank. Or so her father’d said. Owen O’Malley had sailed into London once and only once in his life, but for his two wide-eyed children, the art of his conjuring had forever after painted the city a dank and fetid hole. Yet today Grace O’Malley was blinded by sunlight. The bow of Murrough ne Doe’s galley sliced the Thames like a seamstress’s scissors through a length of glittering cloth—a river of diamonds, it seemed.

Perhaps, thought Grace, Elizabeth would be wearing diamonds when they met. The Queen of England—what would she look like? In her portraits the woman had a strange look about her. Cold. Brittle. Sharp beak nose. And the hard gaze of a man. No, ’twould not be diamonds, Grace corrected herself. ’Twould be pearls. The first Elizabeth, it was said, swathed herself in pearls, both black and white, some as tiny as a bead, some large as a goose’s egg, the rare black ones her favorite.

A din rose from the clutter of docks and warehouses on the river’s north shore. The long, narrow waterfront properties were abutted seamlessly together, ships large and small clamoring for their place at the jetties and water stairs. Brawny shoremen grunted oaths as they labored, loading and unloading vessels, hefting plain and exotic cargoes back to high, timbered warehouses. Carts full of wares rumbled away down cobbled streets behind. The loudest ruckus came from the wharf receiving a shipload of wetfish whose odors—pungent and familiar—filled her nose. Fishermen were the rowdiest sailors, she knew, more so than merchantmen. Pirates even. She glimpsed seamen hurrying to finish their chores. They’d be keen to be done, to leave the ships they’d crewed for weeks or months and swagger down the planks in boisterous bands for a night of brawling and whoring in the world’s mightiest city.

Stretched out beyond the waterfront was the endless sprawl of London’s squat and storied houses, hundreds of streets. Church spires by the dozens pierced the sky, more in one place, thought Grace, than she’d even seen in Spain. Deep in the city rose the tallest of all the steeples, surely the famous cathedral of St. Paul’s. And up ahead was London Bridge, still too far in the distance to see the heads of traitors rotting on their pikes.

Commercial landings now gave way to fine residences, each as large as a small castle, broad lawns sweeping down to the river’s edge. Those were the homes of the great lords, she knew, some of whom had been wreaking havoc in Ireland. The sight tightened a knot in her gut. She must stifle her hatred. Remember her purpose. But here she was, sixty-three years of age. Her maiden voyage into London Town and she was a passenger on a ship not her own. Sure her colors flew below those of Murrough ne Doe O’Flaherty, but it was humiliating all the same. Infuriating.

Well, she had come to remedy that. She would pay a wee call on the queen, at Greenwich, and see about the disturbances. Grace wondered if she was as tall and bony and yellow clackered as they said she was, if the alum and eggshell face paint she wore cracked grotesquely at the corners of her mouth and eyes. If she’d loathe the woman on sight, her energy

for more than thirty years.

She would know soon enough, thought Grace, gripping the rail with her strong, sun-browned fingers. Soon enough indeed.

THE IRISH GALLEY brazenly flying her two rebel flags had, but a moment before, sailed beyond sight of the mullioned window at Essex House. Robert Devereaux, second earl of that name, that house, had come to gaze at the river with an eye to calming his frayed nerves. He’d found that the sight of ships and wherries and barges on the wide, moving ribbon of water slowed a racing heart, measured his ragged breaths, even occasionally lifted the dark veil that had, periodically, fallen since childhood like a shroud on his soul. Out there, the sun glinting off the Thames, life appeared simple, mundane, whilst behind him in his study was a roomful of Queen Elizabeth’s courtiers—friends, relatives, admirers (schemers one and all)—and in their company was every complication of which a man could dream.

Twenty-four, and I am already a great lord of England, thought Essex. He’d recently astonished even himself, being granted a seat at the table of the Privy Council. He was Master of the Horse, a Knight of the Garter, and Elizabeth’s undisputed favorite. Yet I am poor, he thought bitterly, the poorest earl in the kingdom. This, like his title, was a legacy from his father, Walter, first Earl of Essex. He bemoaned that fact every day of his life and cursed his father, altogether conscious of the sin, but cursed him nonetheless. At age seventeen, with Walter Devereaux dead and disgraced in Ireland, and his mother despised by the queen, Robert had to come to Court a penniless lad. Had he owned an ounce less of character and cunning, he often reminded himself, he’d have been swallowed alive by the beast that was Elizabeth’s Court. Instead he had risen more quickly—nay, shot like a star across the heavens—than even his benefactor, the Earl of Leicester, had envisaged he might. Yet it had been tooth and claw all the way to this moment, Essex knew, and whilst the Privy Councilship was assured, his military exploits already the stuff of legend, and his popularity with courtiers, beautiful waiting ladies, and the public equally vaulted, much was nevertheless at stake. His very livelihood! He could remain poor and irritatingly bound in Elizabeth’s debt, he knew, eking out endless loans from the most tightfisted monarch who’d ever lived, or he could, with the stroke of a quill, become a man of status, a man of means.

It seemed a small thing, really. All he needed was her granting to him the Farm of Sweet Wines. The sugar-laden wines imported from the islands of Greece—the malmseys and muscatels, romeneys and bastards—brought twice the levy of other wines, and he had been sniffing round this particular favor since the death, six years before, of its last holder, Robert’s own stepfather, the queen’s beloved Robin Dudley, Earl of Leicester.

Essex needed the grant desperately, for his current financial embarrassment was acute. He had inherited nothing but debt from his father, and there was no way he could squeeze another penny from his various tenants. But with administration of this Farm, even after paying the Crown its part of the customs levied, the profits he pocketed would provide him with a handsome and steady income for the whole of the long-term grant. More important, it would mean security for raising larger

sums of money on credit, crucial for his standing at Court. He would finally be able to afford to redeem his debts to the queen, would no longer be beholden to her.

But how could he wheedle the prize from her?

And was this, in fact, the best use of his time and energies? There were the Bacon brothers to consider, most important Francis. If he could convince Elizabeth to grant his protégé the post of Attorney General, it would benefit Robert immeasurably. But, Essex reminded himself, Francis Bacon had disgraced himself in his first ever Parliament earlier this year by obstructing the passage of an increased-subsidy bill. One did not, Essex knew, and had wrongly assumed Francis knew as well, argue publicly against putting more money in the queen’s treasury, especially to take the side of mere gentlemen, whose finances would be stretched to pay the taxes.

But the deed had been done. Francis had been disgraced…but temporarily, Essex was sure. His own influence with Elizabeth, sweet talk and intimate laughter, would soften her. The post would eventually be Bacon’s.

The gabble of voices behind him exploded into laughter and Essex, planting a smile on his face, turned to join his retainers in good cheer. He’d come to think of the second-floor longhall of Essex House, now his study, as a great hive buzzing with golden bees—the Queen’s Bees—beautiful, forward young men, all of a certain generation. His razor-tongued mother, Lettice, referred to the place as a “nest,” the implication unspoken but nevertheless understood that she described something more akin to a home for vipers than a family of birds.

She was wrong, of course. There was, for example, nothing remotely deadly about Anthony Bacon, thought Essex as his gaze found the tubby, sweet-faced young man, squinting nearsightedly into a large ledger. Though he deftly coordinated a brilliant ring of continental spies, Anthony was far too soft and sickly to be thought dangerous. Essex had rarely known the queen to be so anxious to meet a man as she was Anthony Bacon. It was clear she meant to reward his good works and astonishing network of contacts with a plum position at Court. But each of the many meetings Essex had so carefully arranged between

the two had been canceled as a result of Anthony’s ill health. If it was not a gout so severe he could hardly hold a quill, it was the stone that laid him low. No, Anthony was no viper. Of the four secretaries he managed—juggled might be a more apt description—only one, Henry Cuffe, could be said to claim any ambition at all.

Certainly Anthony’s brother, Francis, boasted a rare and incisive mind. He wrote brilliantly, his extraordinary essays having caused more than a small stir at Court and abroad. He was adept at using others for his own advancement, and recently Essex was the one being used. But this was a quality to be respected and, besides, he was using Francis Bacon equally.

Where was the man? thought Essex. Francis should have been back from Court hours ago.

Essex’s eyes fell on Henry Wriothesley, the Earl of Southampton. This graceful and gorgeous young man stood with his arm draped about his latest “find,” London’s most talked-about poet and playwright. He could see that between his patron and himself, Will Shakespeare held a sheet of parchment that was the subject of their scrutiny—and perhaps their laughter. Southampton had, at twenty, already earned a rightful reputation for profligacy, his warmth and enthusiasm matched only by his petulance and hot temper. Now here was a man worthy of Lettice’s suspicions. In station and title more Essex’s equal than any of the others, and with family and social ties binding them tightly, Southampton was the closest thing Essex had to a friend.

“What, may I ask, is so humorous?” Essex demanded.

“Why, Master Shakespeare has been reading your verse,” replied Southampton, managing to keep a straight face.

“What!”

“The sonnet to your latest mistress. ‘Beneath the Smile.’” Southampton began to read from the parchment and Essex felt his face flush pink, horrified by the poet’s scrutiny of his amateur attempts.

Worthy Lady, think me a man of imperfections, but one that

For your love endeavors to be good

And rather mend my faults than cover them…

Essex snatched the parchment from Southampton’s fingers, forcing a smile he hoped was not too sour. “My private thoughts, gentlemen,” he said, skewering Southampton with his gaze. “Not to be broadcast to all the world.”

“We may be great, my lord,” quipped Southampton, “but we are scarcely the world.” He turned and gazed with open desire at the young dramatist. “You think the poem good, don’t you, Will?”

“I do,” said Shakespeare, holding Essex, rather than Southampton, in his clear, steady gaze. “Your images are bold, and you’ve wisely chosen to eschew the nauseating flowers most amateurs delight in.”

Essex was grateful for the compliment but teased, “What else would you say of it, Will? A too harsh criticism of the queen’s ‘most beloved’ might land you in Irish exile with another poor poet.”

Everyone laughed at the expense of Edmund Spenser, once the court’s most famous versifier, now disgraced for his criticism of William Cecil, Lord Burleigh. In his satirical “Mother Hubbard’s Tale,” Spenser had likened Elizabeth’s oldest and most trusted adviser to a chicken thief. Before he knew what had happened, Spenser had been banished, along with the English army, into the quagmire that was Ireland. Little had been heard from him since.

“Master Shakespeare is too clever to anger the queen.” Anthony Bacon had risen from his bench and approached the group. He held out to Essex a freshly powdered parchment filled with Henry Cuffe’s unmistakable scrawl.

“This is…?” Essex inquired.

“A list of all Her Majesty’s subjects recently sighted at King Philip’s Court, my lord. Papists, all of them. Their purpose, it appears, is to make mischief on the queen’s armies garrisoned in Ireland. And there is rumor of a Spanish invasion to be launched on Guernsey and Jersey. Oh, and the latest report on Philip’s lunatic son, Don Carlos.”

“Very good,” said Essex, beaming at Anthony. His smile was genuine, for this was the sort of intelligence that Elizabeth most craved these days.

The heavy wooden door of the study opened and Francis Bacon blew in, the air of a black storm hanging round him.

“How now, Francis?” Essex called out, careful not to exude more good cheer than the obviously gloomy man could countenance.

Francis Bacon laid down his ledger and bulging document case, sighing deeply. “Beware the Gnome,” he intoned morosely and took the bench recently vacated by his brother.

“What has he done this time?” demanded Essex. “The Gnome” was Lord Burleigh’s son, Robert Cecil—the queen’s secretary—a swarthy little hunchback who seemed determined, at every turn, to make their lives a misery.

“He cornered me in the Presence Chamber this afternoon.”

“In itself a revolting vision,” said Southampton.

He, Essex, and Anthony came to surround Francis, all exuding sympathy. Will Shakespeare, not of this charmed inner circle, hung back quietly, but all ears.

“Patronizing little prick,” Bacon went on. “He began by complimenting my most recent essay, then inquired in that irritating whine if I didn’t think I would be happier with the lesser post of Solicitor General than with that of Attorney General.”

“He didn’t!” cried Essex.

“Bastard,” Southampton muttered.

“What did you tell him, brother?” Anthony Bacon demanded.

“To stuff a stout pig knuckle up his twisted little arse,” replied Francis, beginning to regain his good humor, now back among his friends.

“Seriously, Francis,” interjected Essex. “How did you respond? Are he and his father still insisting on Edward Coke for the position?”

“Of course. ‘A man of experience and levelheadedness,’” he said, in a nasal whine,

imitating Robert Cecil.

“But he made no mention of your parliamentary debacle?”

“No need, my lord. As the Gnome spoke he kept his beady eyes always on the queen, as if to say, ‘She is still angry with you and will be angrier still if you persist in your suit for this office.’”

“Damn him!” cried Essex.

Southampton offered, “If one could die of smugness, he’d be worms’ meat.”

“Was Burleigh there as well?” asked Anthony.

“Thankfully not,” Francis replied. “I could not have borne father and son at once.”

There was silence then amongst the coterie of gentlemen, all lost in the same thoughts, the same memories. “Burleigh’s Boys” they called themselves privately. For each and every one had shared the distinction of growing up a ward of that great lord. After the deaths of their respective fathers, they had fallen under the guardianship of the elder Cecil, and though they had been adequately and appropriately guided through their minorities by him, they had been shown only the most minimal kindness and consideration, whilst the skinny, hunchbacked son, Robert, received all.

After his father’s funeral, Essex—age nine and more sensitive a child than was healthy—had left his home in western Wales to live at Burleigh’s great palace, Theobalds. He’d taken pity on the man’s small, pale, deformed son and heir, had taken pains to entertain him, wrench a few laughs from the overserious child. He’d even on occasion remained behind to play with him whilst everyone else rode after the hounds to hunt or hawk.

But Robert Cecil had, with a soul as sadly twisted as his back, always despised young Essex, loathed his fine opalescent skin, the curly ginger hair, strong, straight spine. Once he’d even fabricated a story of some cruelty perpetrated on himself, a hapless victim of Essex’s wicked prank. Before the year was out, Essex found himself shipped off to Cambridge. The education, whilst premature for a ten-year-old, had been appreciated, indeed embraced, by the precocious boy. Philosophy, mathematics, civil law, theology, astronomy, Greek and Hebrew, dialectic. He had earned his Master of Arts degree by age

fourteen.

But Essex had never forgotten Robert Cecil’s treachery, nor forgiven the blatant nepotism Burleigh had displayed in forwarding his son’s career at everyone else’s expense. The elder Cecil had seen to it that the Gnome had smoothly slipped into his role as secretary to the queen, as though changing partners during a gavotte without missing a step. Father and son together were a powerful force with which to be reckoned, for Elizabeth’s trust in the pair was absolute, and it was imprudent to position oneself on the opposite side of an argument with them.

Such was the case of the Attorney Generalship—Bacon versus Coke. But in this case, all in this room knew, Francis Bacon had more than a fighting chance, as his champion was the Earl of Essex. Elizabeth’s love for Essex was a weapon as mighty as her respect for the Cecil team at its most persuasive.

“I shall see to it,” Essex announced suddenly, strapping on his sword.

“Now?” asked Francis.

“There is no better time than now. The queen misses my company, I have heard from several ladies.” Essex smiled disarmingly and he knew they saw clearly why he was Elizabeth’s favorite courtier. Despite his outrageous disobediences. Despite the childish tantrums. What they could not know, he thought, was that he would use this meeting with Her Majesty to forward more than Francis Bacon’s cause. To be perfectly honest, the Farm of Sweet Wines was uppermost in his mind. Without a small fortune at his disposal, despite his gifts of charm and wit and beauty, he would soon tumble from his place of prominence at Court. Even a brilliant ally in the Attorney General’s office would be of no use to him then.

He must see the queen.

ESSEX HAD NOT expected to meet his mother on his way out, and as he was busy concocting entertainments of the mind for Elizabeth’s pleasure, he found himself startled to come face-to-face with Lettice Devereaux, Lady Blount, at the foot of the great staircase, still in her traveling

clothes.

“Mother, I thought you were in the country.”

“I was in the country, and now I am here in my city house. I sent you word that I was coming to see my grandchild.” Her voice bristled with annoyance, and Essex cursed himself for his forgetfulness. Lettice, still physically luscious at forty, was a cunt of a woman when displeasured.

Essex kissed both cheeks with an heroic show of enthusiasm. “I’m glad to see you, Mother.”

“No, you are not. You and your nestmates prefer me as far from London as possible.”

Essex decided he was in no mood to placate her. “You’re right. It’s impossible to keep Elizabeth even-tempered when she knows you’re flouncing about the city in your gilded carriage trying to out-queen her.”

“Flouncing!” She reached out suddenly and gave her son’s ear a vicious twist. “You were a rude child and you’ve become a rude young man.”

He sighed. “Mother, must we fight?”

The door opened and Lettice’s latest husband, Christopher Blount, entered. Only five years older than his stepson, Blount seemed haggard and had a sour look about him. But this was not surprising, for he had suffered seven hours of a jouncing carriage ride, as well as his wife’s foul humor. Truth be told, Christopher’s sour countenance had lately hardened into a perpetual expression of disgust, the result of a mere three years as Lettice’s spouse…or more to the point, her most recent cuck-older. She was famous for many reasons, but most of all her infidelities. When Essex had been a young boy, his father, Walter Devereaux, had become the cuckold of the Earl of Leicester, and after Devereaux died and his mother had married Leicester, she’d cuckolded him with Blount. Essex wondered if the wan, irritated face of his current stepfather was at least partially a result of his cuckolding by Lettice’s newest amour.

“Hello, Christopher, and good-bye.” It had taken only a few moments, but Essex was now incapable of remaining in his mother’s presence. “I’m off,” he announced, not bothering to hide his relief at going.

“Robert!” Essex’s hand was already on the door latch when his wife’s voice stopped him. He sighed and turned back to see Frances coming toward the group at the door, carrying their infant son. Lately, just the sight of his kindhearted and dreadfully dull wife caused an upwelling of confused emotions in his chest, for she moved him so little. Even his firstborn child elicited only the weakest surge of affection. These feelings he knew to be entirely unnatural, and it worried him, agitated his soul. What kind of man was he, so unmoved by his own family?

“Frances, you’ve caught me on my way out.”

“To Court?”

“Yes, my love,” he said, reaching out to caress the babe, Robert, named after himself. Essex was at least careful to keep up the pretense of familial affection.

“Send my love to the queen,” Frances said with true sincerity. Their relationship was as long as his wife was old, as her father, Lord Walsingham, had for so many years served Elizabeth in the closest and most vital capacity—spymaster. Frances’s first marriage to Elizabeth’s godson, Philip Sidney, had strengthened the bond to such a degree that when she had secretly married Essex after Sidney’s tragic death, the queen had forgiven the indiscretion in record time. Others—Leicester, Raleigh—had spent time under house arrest or in the Tower of London for contracting marriage without the queen’s permission. Essex had always believed it was Elizabeth’s love for Frances that had lightened their punishment to a mere slap on the wrist.

“I’ll give her your kindest regards,” said Essex and again made for the door. Lettice’s hand was laid over his before he could open the latch. “Dear son.” Her voice had changed. It was warm and silken, like her skin, and he felt gentleness exuding from her, as sweet as it was false.

“Yes, Mother,” he said, groaning inwardly. He knew he’d not have to wait long to learn what it was she wanted from him.

“You will speak to my cousin the queen once again about our meeting.” It was more a

command than a request.

This was the last subject Essex wished to broach with Elizabeth this day. Any day. All previous attempts at reconciling the queen with the woman who had secretly married the one man she had ever truly loved had ended in disaster. Had Lettice been one iota less arrogant, ostentatious, or heart-stoppingly beautiful, perhaps Elizabeth would have forgiven her, allowed her back at Court. But his mother, in all the years of her marriage to Leicester, had refused to be cowed by her royal cousin. She was, after all, a grandniece of the queen’s own mother, Anne Boleyn. Lettice was proud to a fault, and whilst still Lady Leicester, she had flaunted that title, her husband’s wealth and status, driving Elizabeth to furious distraction. Now married to a mere boy, a nobody, Lettice knew her position to be vulnerable, possibly dangerous. And she had recently begun seeking a rapprochement with the queen. Of course she would use her son’s exalted position to forward her cause.

“I cannot promise I’ll speak to her today, Mother,” said Essex. He felt, rather than saw, Frances stiffen at his response. Once he had left, she would bear the brunt of Lettice’s outrage at her son’s insolence.

“Robert.” His mother’s voice was threatening and her grip on his hand tightened, but with his other hand he pried off the vicelike fingers.

“I am going now,” he said in a cold, clipped voice that brooked no argument. He turned to Frances. “I may return home tonight, or I may stay in my apartments at Court.”

She nodded and smiled weakly. “Wave bye-bye to your papa,” she said, flapping little Robert’s hand. Essex felt sick leaving his wife and son with the dragon, but his urge to escape was greater still.

It took all of his restraint to close the door quietly behind him and squelch a whoop of joy. Once outside in the sunlight, the prospect of an evening in Elizabeth’s glittering Court ahead, Robert Devereaux, Earl of Essex, found his mood had brightened considerably.

ESSEX LOVED the brief water transit from his home upriver to Greenwich castle, and

the early September gloom that had quite suddenly fallen over the Thames did nothing to dampen his mood. He enjoyed the bustle, the noise, even the stink of it, for he saw the river as the lifeblood of London. Riches were ferried into the city on these waters, as well as the most famous and infamous personages, and the most vital intelligence from abroad. All great enterprise originated here. Each time Essex came out on his mother’s gilded barge, memories sailed across his vision like the tall-masted ships towering above him.

He remembered his first entrance into the city as a boy, awe of the place bulging his innocent’s eyes. He thought of the day Leicester had taken him, a nervous seventeen-year-old, to be presented to the queen. His aging stepfather had personally overseen Robert’s dressing and polishing for the event, and whilst on this very barge had proffered last-minute tutoring to guarantee, he hoped, Elizabeth’s acceptance. He recalled the glitter and breathless excitement of his first evening water party, seated at the queen’s right hand, the river reflecting the exploding fireworks overhead. Essex saw again the night he had secretly spirited himself out of London on the Swiftsure, hiding from the queen his sudden departure, and his rendezvous with her fleet, which was headed for an attack on Lisbon. Elizabeth had previously demanded that her new favorite attend her at Court, expressly forbidding him to join Francis Drake’s raiding party of King Philip’s second Armada lying at anchor in Lisbon Harbor. Risking royal displeasure, Essex had, with clandestine precision, outfitted the Swiftsure at his own expense, and with blatant disregard of her orders, had joined the expedition already at sea. Some thought him merely foolhardy, others outrageous, but his brave—if theatrical—exploits in Portugal had profited him enough fame to outweigh the queen’s displeasure. His reputation as a national hero had sprung from that journey, and a popularity so broad that the long, square, “shovel-shaped” beard he’d returned wearing had quickly become all the rage in London, with nobles and common men alike copying the style. And the journey had begun here, on the River Thames.

In the space of his musings, the barge had reached the Greenwich quay. As he

disembarked Essex began again the obsessive argument with himself of whether to discuss, first, the subject of Francis Bacon, or the Farm of Sweet Wines, and therefore barely registered the hubbub that surrounded the almost barbaric-looking galley docked beside him. The Dockmaster was engaged in a heated exchange with the ship’s captain, but Essex dismissed it. Shiploads full of exotics and extravagances had been arriving for weeks now, in preparation for the queen’s sixtieth-birthday celebration, a round of festivities that promised to eclipse all those that had come before it, and he took no notice of several guards trotting from the tower gate up the elevation toward the galley.

Greenwich was a great, redbricked hodgepodge of a castle, whose long main wing with its row of high, transited windows overlooked the river. Essex moved along the brick path to the south gate, accepting greetings from gentlemen of the Court—young and old, high peers and eager hopefuls. Their demeanor was deferential, even, he thought with an inward smile, reverential. He, of course, returned the salutations with a warm grace that never failed to delight the recipient. Essex’s pace was leisurely, with an eye to prolonging the pleasure of adulation, but today there was further reason to take his time. He was playing a game with himself, wondering where he would find the queen. He prided himself on knowing her well, guessing her mood. He’d even memorized her schedule. Now as she grew older it became more regimented, both daily and weekly.

It was late afternoon, and Elizabeth would have done with her dozens of audiences, he reasoned. She would be finished with the endless pile of paperwork that she’d attended to, sitting straight backed at her desk as the secretaries Walsingham and Cecil laid the documents before her. He could picture them waiting patiently as she marked them with her studied and flourished signature, to be set carefully with a vellum roller and the finest perfumed powder from France. She would already have taken her exercise, perhaps a brisk walk upon the castle’s battlement—she had ridden out with him yesterday—and would have completed her daily translations and double translations of Greek classics, her favorite hobby, she claimed. Today was Monday, and there was very little planned for the evening. A light meal taken in her rooms. Perhaps some music, but no dancing. Perhaps a night of gambling. Essex hoped this was the case, as the pleasure of dice and cards always cheered Elizabeth…made her more

receptive, even to his “incessant nagging,” as she’d come to call his more and more frequent requests for favors.

So, he reasoned, if it were not to be a formal evening, her late-afternoon toilette would be abbreviated, perhaps she might even forego changing her gown. If this were the case, where might the queen be just now? A fitting with her seamstress was possible, or a meeting with her Master of Revels in preparation for her birthday celebration.

No! None of those places. Essex was suddenly sure he knew her whereabouts. All at once three of Elizabeth’s ladies burst from around a corner into the wide corridor, gorgeous in their varicolored silks, fluttering and chattering like a trio of tropical birds. He breathed easier to see that Katherine Bridges was not among them. His latest mistress was entirely delightful and, a married woman, never demanding, but Essex was at this moment seething with single-minded purpose and wished for no distractions. He nodded with graceful exaggeration to the ladies, fixing each of them in that moment with a private, hungry glance. It was prudent, he had discovered, to keep the women of the Court in a state of mild but constant desire for him. Favors of every sort were far easier to extract that way.

Without bothering to confirm his guess at the queen’s present location, he turned into the corridor of the castle’s north wing; Essex strode past the now deserted Privy Council Chamber, nodding to the two guards, both of whom sported the squared-off beards, standing at attention at the heavy wooden doors. He took great but secret pleasure from the fact that the place was now one of his official destinations. The Privy Council table was the very heart of government, and he was at home there. Indeed, the other Privy councilors, all older and, they believed, wiser, were forced to begrudgingly admit that Essex was a faithful and hardworking cohort. No one, in fact, spent more time at Council business. No one demonstrated more raw enthusiasm for the job. He was young and wild and too well loved

by the queen for his own good, but the older men were, in the end, forced to agree that he was a brilliant logician, a clever tactician, and regularly spouted unique solutions to previously insoluble problems.

A final turn down a short hall found Essex at a doorway undistinguished other than by the two armed soldiers who guarded it. At sight of the men, he silently congratulated himself, recognizing them as Elizabeth’s personal guard of this hour, who protected whichever room in which the queen was present. He greeted them, warmed by their obvious admiration for him. They were common men, brave soldiers who had seen battle, and they respected him. The public, he knew, perceived him, despite his title and standing with the queen, as a man of the people. He liked that, liked that he was welcome in the company of low-or highborn men.

When Essex entered, the guards uncrossed their halberds and opened the door.

As ever, the sight of Elizabeth amazed him, paralyzed him. Bathed in orange afternoon light, she stood for her portrait wearing a low-bodiced, brocaded gown, draped round in a robe the color of fire. Her eyes were fixed on the young Flemish artist, and though she had not turned when the door opened, Essex was sure she knew it was he who had entered. Quietly he shut the door behind him and, moving behind Marcus Gheerhaerts, settled himself on a bench, the better to gaze at the queen and the nearly completed portrait.

There was a fabulous quality to the painting, undoubtedly the most sumptuous and beautifully wrought that he had ever seen. In ways, it recreated Elizabeth in shocking, lifelike reality, yet it imagined much. It sang with allegory, Gheerhaerts having planted dreamlike, mythical elements at every turn, allowing one to stare endlessly at the portrait and continue discovering its mysterious details.

Despite the pale gray that shadowed Elizabeth’s temples and cheeks, the artist had chosen to depict the queen’s angular features with a lush roundness, a fullness of the lips and breasts, the soft, sloe-eyed gaze of a lover. ’Twas as though the painter had chosen to see the woman at her life’s ripest moment. The way, thought Essex, that Leicester had described Elizabeth in her thirties, when they still shared a bed.

The gown’s high, rounded ruffs were such fine gauze as to be transparent, only

noticeable by their jeweled borders, and the tips of the proud, feathered headdress that evoked Diana, goddess of the hunt, were lost beyond the top of the canvas. Her wig, hung with huge, teardrop-shaped pearls, was the color of fresh carrots, its long, curled tendrils hanging down along her bosom. Pearls hung as ear bobs, ropes of fat pearls encircled her neck as well as a necklace dangling in the cleft of her pale raised breasts. On her puffed left sleeve, a jeweled snake symbolizing fidelity was made all of pearls and twisted into a love knot, whilst the serpent grasped in its mouth a red ruby heart.

Clearly Gheerhaerts had reworked the fire-colored cloak draped round Elizabeth’s left shoulder and right hip since Essex had seen it last, for now it was dotted—most extraordinarily, he thought—with eyes, ears, and mouths! This young Netherlander, thought Essex, must indeed have studied the queen’s life in some detail before beginning his portrait. How else would he have known to symbolize in his rendition of her the three most important men in her life? From the earliest days of her reign, Elizabeth had literally called Leicester “My Eyes.” Walsingham, her master of espionage, was “My Ears” abroad. Old Burleigh, bottomless well of wise counsel that he was, who most often spoke the words the queen herself was thinking, would, had she given him a pet name, surely have been “My Mouth.”

But by far the most disturbing new object in the painting was a long, arched tube of some vaguely transparent material, perhaps frosted glass, that Elizabeth grasped with the thumb and four fingers of her right hand. Whilst posing she had been instructed to hold the doweled back of a tall chair, and since Essex’s last viewing—through strange turns of the artist’s mind—the dowel had transmogrified into this surprising element. Parts of her dress could be glimpsed through the tube, very peculiarly, and it seemed to dissolve into her cloak at the level of her groin, disappearing to become part of the yellow-orange fabric. But now, on closer observation of the arched tube, Essex could see along its front curve a rounded ridge. It was

most astonishing. For at the very place where Elizabeth grasped it lightly with her long delicate fingers, the object most resembled in size and shape a man’s erect member.

Surely the queen had viewed the portrait’s progress. She must have observed the object and the erotic nature of its appearance. Had it disturbed her—as it now did Essex—she would certainly have had it painted out. Why did it unsettle him so? he wondered.

In that moment Elizabeth, looking past the artist, met Essex’s gaze. Nothing in the calm repose of her features changed except the deep brown, almost black eyes, which bid him warm welcome into her world. She was pleased to see him. But in that moment of connecting their souls, Essex realized the nature of his discomfort at the painting’s raw sexuality. He began to blush like a schoolboy, turned from Elizabeth’s gaze, and walked across the room pretending to see something of interest out the mullioned windows.

“Careful, my lord Essex,” Gheerhaerts warned, “you block the last of my precious daylight.”

“Sorry.” Essex moved again, refusing to acknowledge Elizabeth’s amused expression.

“And you, Majesty,” the painter commanded, “please do not smile.”

Essex willed himself to a state of calm, but all at once he was lost, four years in the past, remembering.

1589. Leicester was not long in his grave, but he had died on the heels of England’s stupendous victory over the Spanish Armada, and so whilst all celebrated, Elizabeth grieved. The queen had been forced by circumstance to publicly rejoice in her navy’s triumph, but so much of her soul had died with Robin Dudley, her suffering so private and terrible, that it was only with the greatest of effort that she managed every day to place one foot before the other and continue to rule.

Essex, only recently installed as Elizabeth’s newest favorite, was—aside from herself—perhaps the only individual in England with any reason to mourn the widely despised Earl of Leicester.

Leicester was the one man who had taken great pains with the young Earl of Essex’s grooming and advancement at court. Sensitive and observant, Essex had emulated Leicester’s best qualities—a cutting wit and a fine intelligence, riding impeccably, excelling in the martial arts, dancing superbly.

And, Leicester had pointed out, his stepson had been blessed with the physical traits that all her life the queen had found irresistible in a man. He was tall—taller than she—broad shouldered, with thick red wavy hair and beard. Both of the queen’s true loves—Thomas Seymour and Leicester—had shared those very qualities with the first man Elizabeth had ever adored—her father, Henry VIII. Even at eighteen, Leicester had insisted, his protégé had the bearing of a king—a man his queen could admire, could advance. Could love.

There had never been a conscious plan to seduce Elizabeth. After Leicester’s death Essex was, however, the one courtier whose company the queen constantly craved. Though they never spoke of it, she understood that the young man sincerely missed his stepfather, and his sympathy for her loss was genuine. They’d spent more and more time together, riding, dancing, gambling. It was not long before she began to call him Robin, which at first he believed had been a mere slip of the tongue, but later realized had been a conscious, if uncharacteristically sentimental, decision. He had, surprisingly, found her physically attractive at fifty-five and always exciting, but never discovered how much of her allure was genuinely erotic and how much was owed to her status as the most powerful woman in the world.

He engaged her in spirited debates on the finer points of Greek literature, enjoyed long, loud arguments over a word or phrase whose translation was questionable. She adored gambling and he matched her, bet for bet. She knew he played his best at dice and cards, and she beat him roughly half the time. He had learned how to make her laugh and begun to crave hearing the bawdy bellowing from such an otherwise dignified personage. Their evenings together began extending all through the nights, he not leaving her rooms until the sun had begun to rise.

He was nevertheless unprepared when, as he was helping her down from the saddle after a hard ride, Elizabeth had slid effortlessly into his arms and returned, with as much fervor as it had been delivered, a kiss he had not consciously intended

to bestow. He never knew who had been the more surprised of the two, for the queen knew better than anyone that she was quite old enough to be his mother, indeed his grandmother. But that night she had led him more than willingly into her bed and he, suffering from a blinding enchantment of the moment, had followed.

Hardly a virgin, he’d endeavored to dazzle the queen with his manly prowess and he was sure—from the abandon with which she touched him and moved, and how in the end she had cried out ecstatically—that Elizabeth had been fulfilled in her womanly pleasures. Afterward, when they lay side by side, she had held his still erect manhood in her delicate white fingers and wondered at the tirelessness of youthful passion.

Then she had risen quite suddenly from the great Bed of State, pulling her robe around her. Essex had watched as she’d moved to the silver-framed looking glass and commenced staring at her own reflection. He had spoken very little in their tryst, and when he’d found enough voice to call her name, she raised her first finger to him as if to silence him, as if she were too heavily engaged in a discovery of great import to be bothered. So he had lain quietly, watching her.

Shortly, he felt the air changing in the room, growing cold where moments before it had glowed with red heat. He became alarmed as her self-observation in the glass continued on and on. With dawning horror he realized she must be seeing the web of fine wrinkles, the pockmarked cheeks and forehead where the face paint had been kissed away by the boy still lying in her bed. Then he saw Elizabeth stiffen, saw her raise herself up to her full height, and never meeting his eyes said, in the gentlest voice he had ever heard her use, that he should go. She was very pleased with him, she was careful to say, but when she’d tried to continue, her voice had cracked and thereafter she had stood motionless, still staring into the looking glass.

He’d risen and quickly dressed himself. When he moved toward her, she lifted

her finger once again to stop him from approaching, but he would not be stopped. He had been her lover this night, not a boy she could hold back with a gesture or even a queenly command. He took her shoulders and turned her full to face him and saw tears of sheer misery shimmering in her eyes.

“I am yours, Elizabeth, always yours,” he said simply, then kissed her. He had prayed in that moment that she might melt into his arms, cling to him again, forgive herself her age and ugliness so that she could let herself love him as she had Robin Dudley. But she did not soften, did not speak. Only silently bade him go.

Thereafter she had heaped honors on Essex, favored him above all her other men. She showered him with affection, openly caressing and embracing him. She made him many rich gifts and continued even to call him her “Robin.” All the Court knew of their tryst and she had not disabused them of her change of heart. As far as her ladies and gentlemen were concerned, she and Essex were, in the truest sense, still lovers. But never once after that night did she allow him into her bed.

The depth of his hurt had surprised him. He’d not realized the precise nature of his affection until her rejection of him, and he was faced with the truth: Elizabeth was not a trophy. He took no pride in the accomplishment of bedding the Queen of England. He had loved her as a woman. Worshiped her body. Joined his mind and spirit with hers. He had never felt so deeply for anyone. Ever.

She had refused to allow him to leave Court, even to privately lick his wounds. He had desperately needed time to think, to ponder his heartbreak. His grief was therefore protracted, his understanding delayed.

It came to him

one afternoon when his mother had summoned him to attend her on a matter of finance. They’d sat side by side poring over the household ledger. Lettice had been haranguing him for several minutes regarding some gambling debts, though he knew her recent bitterness was in large measure caused by his love affair with the queen, one that recalled her second husband’s obsession with the same woman. As her tirade had continued, he refused to meet her eye. Now as he turned to face her the sound of his mother’s voice faded and her lips moved in silence. The strangeness of the event rattled him, but he was suddenly aware that he was seeing Lettice clearly for the first time.

She was a bitch and a whore, and she had never loved him. Had never even seen him. She’d neither rejoiced in his brilliance nor accepted his shortcomings.

Elizabeth had.

He was forced to turn quickly before the tears overflowed his eyes and his mother think him hurt by her ranting. Risking her fury he excused himself, claiming one of his sick headaches, and locked himself in his rooms.

He lay motionless on his bed. His thoughts were jumbled, memories flooding his mind. A severe childhood fever, cared for by his nurse, Lettice never once coming to his bedside…his father raging before the fire at his cold, faithless wife…the queen’s face softening as she silently read the small verse he’d written in her honor…at a New Year’s feast, Elizabeth’s long white fingers affectionately tickling his neck…those same fingers lightly grasping the hardness between his legs. Elizabeth…

He knew enough to realize that the rejection from her bed was a matter of personal vanity. She was too proud to ever again be seen in her imperfect nakedness by any man. But she loved him nevertheless. Would keep him near her, forward his career…forgive him his tantrums and indiscretions. He was, he realized in that moment, to be the last man to whom Elizabeth would ever give herself.

“Robin…”

Essex was wrenched from his reveries. He turned to see the queen standing behind him in her white, brocaded gown. Gheerhaerts had involved himself in cleaning his brushes, and the solid orange robe on

which the artist had imagined embroidered eyes, ears, and mouths now hung in careful folds over the top of a tall screen.

“Majesty.” Essex bowed low and, taking Elizabeth’s hand, kissed it with delicate passion.

“You’re very pale,” she said. “Are you ill?”

“I could be if it would make you fawn over me this evening,” he teased.

She smiled indulgently, a self-conscious, closed-mouth smile. Her ivory teeth had recently begun to turn brown. “What do you think of the portrait?” she said.

“I’ve already told you,” he replied, loud enough for the artist to hear, “that I do not think Master Gheerhaerts is doing justice to your beauty.”

The queen was used to indiscriminate flattery, knew most of it to be false, but demanded it all the same. It had become a ritualized form of greeting that was necessary before genuine conversation could begin.

“How are Frances and little Robert?”

“Excellent, Your Majesty. She sends you her love…as does my mother,” he added, quite surprising himself, as he had not expected to raise the subject of Lettice this day.

“Is she still yearning for an audience?” Elizabeth asked, taking his arm and indicating that he should escort her from the room. With a tap on the door, it flew open and the two of them exited into the corridor.

“You know she is,” said Essex.

“Then she shall have one.”

He was bemused by Elizabeth’s sudden acquiescence on so prickly a matter.

“Arrange it for next week.”

“I’m most grateful, and so will my mother be.” He felt his heart suddenly thumping in his chest. This was a great coup. Lettice would be overwhelmed. But he must carefully steer her from any ostentatious displays

in either her dress or mode of transport to the meeting. It would not do for her to arrive for the long awaited occasion arrayed in one of her expensive French gowns, riding like royalty in a gilded carriage pulled by six plumed, white stallions. His mind raced. The queen’s mood was more than affable today. Should he broach the Farm of Sweet Wines, or Bacon’s appointment? Or should he perhaps consider mentioning neither of them? He pondered the question as they moved with stately grandeur down the long corridor. Every man who passed stopped and bowed. Ladies ceased their tittering and gossip and dropped into deep, solemn curtsies.

“So,” said Essex, “shall we play at cards this evening? Or dice?”

“Neither,” said the queen. “You already owe me far too much money. You, my lord, cannot afford to lose another shilling. In fact,” she added, “I am wondering when I shall see my three thousand pounds repaid to me.”

He had his opening!

“I was thinking just now, Your Majesty, that if I were granted the Farm of Sweet Wines, I could easily repay the debt. Within a year. Two at the most.”

“The Farm of Sweet Wines?”

Elizabeth appeared surprised by the request, but he knew she was playing with him. Like the Mastership of the Horse, the Farm had been one of Leicester’s grants—indeed his predecessor’s principal source of income.

“That is a very rich gift you are suggesting I make you, my lord.”

Her voice and mood were suddenly unreadable. Essex knew he was on dangerous ground.

“Perhaps if you made your queen a gift…” she began but didn’t finish, as her attention was drawn to the figure now approaching them. “Ah, Robert.” She extended her hand to be kissed by the graceless Robert Cecil.

Essex seethed quietly. The Gnome had destroyed his moment.

“Your Majesty. My lord Essex.” Cecil’s voice was urgent. “I’ve just learned that an enemy of England has had the temerity to sail upriver and dock at the castle quay.”

“An enemy

of England?” said Elizabeth. “Who?”

“The Irish rebel, Your Majesty. The woman…the pirate…Grace O’Malley. She is”—Cecil was flustered and could barely say the words—“demanding an audience.”

Elizabeth began to move down the hallway flanked on either side by Essex and Cecil, in long strides with which the Gnome could hardly keep abreast. The queen seemed altogether undisturbed by the strange news. On the contrary, she seemed delighted.

“So,” she said, “‘the Mother of the Irish Rebellion’ wishes to answer our interrogatory in person.”

“So it seems, Your Majesty,” Cecil answered.

Essex was annoyed. Whilst he certainly knew who Grace O’Malley was, he had no knowledge of an “interrogatory,” and neither Elizabeth nor the Gnome seemed inclined to apprise him of its mysterious contents.

Neither would he give them the pleasure of begging to be informed.

Elizabeth was silent as they followed her toward the Privy Council Chamber. Essex sensed that her mind was working at a most accelerated rate.

“Robert, bring me a copy of her answers,” she snapped at Cecil.

“Yes, madam.” Without another word the Gnome peeled away from them and disappeared back the way he had come.

Essex and Elizabeth reached the Privy Council Chamber and the guards flung open the double doors.

“Will you see her, Your Majesty, or have her arrested?” Essex finally asked. He was becoming more and more irritated. An “interrogatory.” Her “answers.”

Elizabeth did not deign to reply. He persisted. “Grace O’Malley has the distinction of having transported more shiploads of Scots mercenaries to Ireland to fight the English than anyone else in history.”

“Sometimes the Scottish Gallowglass fight on our side,” Elizabeth argued with infuriating calm.

“The woman is a

traitor many times over, Your Majesty. A known cutthroat!”

“She is indeed. But our Philip Sidney thought enough of her to continue a long correspondence, from the time of their meeting in Ireland till his death. And her answers to my questionnaire have piqued my curiosity. Despite her reputation I believe she has something in her character to recommend her. I wish to see such a woman with my own two eyes. See what she is made of.”

Elizabeth saw Essex’s frustration growing, and obliged him. “She recently asked me for several favors.”

“Favors? From a known rebel?”

“I replied with an interrogatory of eighteen items. She responded in early July.”

“But—”

“You will have the Presence Chamber readied for an audience,” Elizabeth interrupted, irritation growing in her voice. “And see if my Irish cousin, Tom Ormond, is about. I know he’ll wish to be present.”

Essex stood unmoving, entirely bemused. The queen’s temper was rising.

“Robin, listen to me now,” she said, fixing him with a look of grave intensity. “You have been so preoccupied with your military obsessions and your Bacons and your Farm of Sweet Wines that you have not been paying attention.”

“Your Majesty, I object! I have been paying very close attention to your business and the business of state.”

“Yes, you have. My domestic agenda. But what of my foreign policy? What of Ireland? You know nothing about the rebellion there. You shy away from the subject, as most men do, because the very thought of that savage country makes your blood run cold. When you do think of Ireland, you’re reminded of all the Englishmen who’ve died there. Were ruined there. Your father, for one. Your brother-in-law, Perrot, for another. But you don’t think about my Ireland. My problem.

“Did you know, Robin, that the last act of my mother’s betrayer, Cromwell, was to talk my father into taking control of the Irish nobility? His “Surrender and Regrant” policy was either the most brilliant idea he’d ever

conceived, or the most boneheaded. Who knows, perhaps Thomas Cromwell was the first of Ireland’s victims. He died by the ax not three years after the program’s conception. My father paid it halfhearted attention. It was a distant problem in my brother’s reign, and even in my sister Mary’s.

“But distances have shrunk, my sweet man, ever since the Spaniards began their bloody conquest of the world, and Ireland is suddenly at my back door! Philip has dangerous papist allies there—confounded Irish aristocracy! There’s one and only one amongst them—Tom Ormond—who knows the true meaning of loyalty. The lords of that unfortunate land blithely swear their fealty to my governors one day, then slaughter my troops the next. I send colonists there, soldiers and horses, and they die of disease or battle or go insane. The Irish are an unfathomable people,” she said, looking away, then added, almost to herself, “I worry they’ll be the death of me.

“My treasury is hemorrhaging money. If I continue raising taxes, my people will come to hate me. I cannot afford this war, Robin! And I cannot afford your ignoring it any longer. If you wish to be my most trusted adviser—and I know you do—then you will henceforth educate yourself on this matter, interest yourself in it, because it means very much to me, and will in the future mean even more.”

“Yes, Majesty.” Essex was humbled, knowing her altogether right, and grateful that she understood him so well. She tutored and directed him in the affairs of state, was so forgiving.

“Go along now,” she said, as if he were a mere page and not a New Man of the Privy Council. “See to the audience. And pay attention in this lady’s presence. She may be a traitor to England, but she has much to teach us both.”

Essex exited as Robert Cecil returned bustling with importance. He had a rolled parchment tucked beneath his arm. As the doors closed behind him, Essex could see him spreading on the long table what must have been the pirate O’Malley’s answers to Elizabeth’s interrogatory. He chided himself for allowing the Gnome to best him on Elizabeth’s most pressing foreign affairs. He’d kept abreast of the war in the Netherlands, of Scotland and France, and Spain’s continuing crusade to

convert to Catholicism every man, woman, and child who lived. But he had dismissed Ireland. The queen’s attempts to colonize it, and the great rebellion it had spawned, had escaped him. But no longer. He would make it his business to understand that strange hellhole of a country.

And he would begin with Grace O’Malley. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...