- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

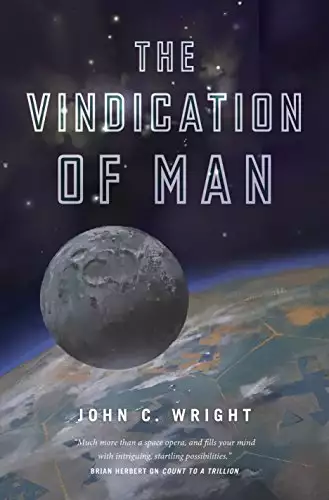

The Vindication of Man is the epic and mind-blowing continuation of John C. Wright's visionary space opera series surpasses all expectation.

Menelaus Montrose, having renewed his enmity with his immortal adversary, Ximen del Azarchel, awaits the return of the posthuman princess Rania, their shared lost love. Rania brings with her the judgment of the Dominions ruling the known cosmos, which will determine the fate of humanity, once and for all. Vindication or destruction? And if it is somehow both, what manner of future awaits them?

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: November 22, 2016

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Vindication of Man

John C. Wright

The Sound of Her Voice

1. A Bad Call

A.D. 68010

As he woke in his selective fashion, layer by layer, the central node version of Menelaus Montrose wondered if he had made a bad call.

Was he losing his nerve? Was he losing his mind?

Just to check, Montrose called a forum of his ulterior and inferior minds, including archived templates, remote units, and singles. The consensus mind briefly formed and ran through some twelve billion quotient-seconds of self-calculations, including that branch of specialized cliometry reserved for coordinate minds predicting their own behaviors over the long term.

Both the superhuman and subhuman versions of himself returned the answer that, yes, he was losing his grip.

“But why?” Montrose called out across the many channels linking his mind spaces together. “I am just the same as I always was!”

2. His House

Where the Mediterranean once had been was now a mountain range. What had once been the land between the Nile and the Congo was now an inland sea called Tethys. The southern continent was called Pannotia, and the northern Baltica. Millennia ago, when this northern coastline of Baltica had been inch by inch submerging into the Atlantic, Montrose had bought this tract of land on speculation, since the long-term tectonic plate movements planned by Tellus foretold that this land would rise once more above the sea in the seventeen thousand years before the return of Rania. And he grew and built a house here, relieved, for once, that he had no need to lock himself into a hidden and heavily armed subterranean tomb.

Years passed, and the land sank, and more passed, and it rose again. Hills to either side of him first breached the waves, forming an island chain, and the uplands rose, forming a peninsula, and now his land was in the midst of an isthmus reaching between the mountains of Cambria the plateau of Normandy. The hills and uplands of what had once been the English Channel pushed their green and pine-clad heads into the icy air, all save, ironically, the acres where he’d placed the main house.

So at the moment, he was somewhere under the waters of a loch, which was under an ice layer, in the middle of a diamond-walled mansion so old that it had been on the surface when last he checked, and so smart that it simply adapted to the changing environment, and replanted the hedge mazes surrounding the main house with sea plants and corals.

The diamond mansion had both roots striking down to subcrustal information cables and branches reaching up through the lake water to thrust naked twigs above the ice layer. These antennae grew or shrank as needed. They could receive and send signals to convenient orbitals or towers sixty thousand miles high, reaching from anchors affixed beneath the mantle to geostationary points in orbit. Through these antennae he could reach other versions of himself, in other stages and conditions of awareness, seated elsewhere.

3. His Hierarchy

At his cry of despair, somewhere in the depths of the logic diamond core of the planet, two of the Archangel-level supermontroses, beings of intelligence in the ten thousand range, exchanged information signals corresponding to wry glances, or prodding the inside of one’s cheek with a tongue.

Meanwhile, a hypersupermonstrose, who existed intermittently at the Potentate level in the eight hundred thousand intelligence range, was like a looming statue in the background of the shared Montrosian thoughtspace. He sent a brief, sardonic message to the forum: “Oh, surely so. Poxing pustules on my peck! We’s just as human as ever. Rania is almost here! Nothing else matters!”

But it was the singles, of intelligence between two or one thousand, some of whom occupied human-formed bodies in near-Earth orbit, or on the upper or lower levels of the vast space elevators rising by the dozen from Terra’s recently formed unbroken equatorial mountain range, or bodies larger than whales swimming in the sea, or in the flooded tunnels running through the mantle of the Earth, who answered back, “You need a priest. You need confessing. Something gnawing at your gut, and you ain’t man enough to face up to it.”

“Why do you say that?” the central Montrose, still half-awake, demanded.

“What do you feel guilty about?” came the message from the consensus forum of Montrose-minds.

That particular central Montrose, who was in the act of waking up, his attention divided between the smarter versions and the simpler, suddenly halted the waking process.

Montrose said to himselves, “Guilty about what?”

No doubt it would have been quicker to wake the Potentate level version of himself, but such extraordinary minds used up extraordinary amounts of energy and infrastructure rather quickly. Unless he wanted to go out into the current world and work for a living—or beg or steal—to get the resources to support him and his infrastructure, it was better if the giant slept.

He was also haunted by the memory of a particular high-energy version of Montrose who once had been admiral of the Black Fleet, back in the old days, during the coming of Cahetel. He had slain himself, or let himself be slain, which was much the same thing. Whatever else had been in his memory and experience, thoughts, visions, dream, ambitions, ideas, everything from that slain version was gone. Montrose often put the lost section of his life from his mind, but it just as often returned, like a tongue that cannot help but seek out the hole left by a missing tooth. It was as if a stroke had left a blank spot in his mind.

“And what if the smarter version of me sees something I cannot poxing stand to see? Is he going to commit suicide also? And take me with him?”

They answered back, “Rania wouldn’t like that.”

Another version looked at the calendar. “Why am I waking up now? What has happened?”

It was the Sixty-Ninth Millennium. A thousand years before her return. The last tiny sliver of time. A negligible amount of time. A hiccough. He could do it standing on his head. One more nap, and she was here.

So why did he keep waking himself up?

The Potentate Montrose, buried in a matrix of black murk somewhere near the core of the self-aware world, renting part of the Tellurian Mind, answered softly, “Psychological weakness.”

“You’re poxing me.”

“No pox. You were beaten by your mommy as a boy, and this made you strangle on apron strings from then to now. You are afraid of women; afraid you cannot be the boss, play the man, take command. You think Rania is too good for you.”

Montrose said, “That ain’t the reason. I don’t buy it.”

“You should buy what I sell. I am a far piece smarter than you, after all,” said the Potentate Montrose.

The two Archangel Montroses, far less in intellect than the Potentate, but immensely smarter than the waking version who tossed and mumbled in his coffin egg and served as the mental phylum’s central node, both said in slightly different wording, “But all our sins and fears and neurotic little twitches we built up over the years, they, too, get all big when we get all big. The black spot on a balloon expands when the balloon swells up, don’t it?”

Central Montrose said, “I should be able to throw the clock out the window, shoot the rooster, turn over, stuff my head under the pillow, and go back to sleep. But I am tossing and turning. I thought things were … I dunno … settled.”

“What’s keeping you up?”

“I am just worried about whether I made a bad call, that’s all. You know.”

They did. He was worried whether the price he paid for that tiny little seventeen-and-a-half-thousand-year nap was too high.

4. While He Slept

He and Blackie had a deal. No more meddling in history, no more duels, no more nothing until she got back. They had not technically shaken hands on it, but Blackie had agreed! It had been so close, so soon, less than eighteen millennia! A pittance!

Dark ages followed bright in rapid succession. Twice more the aliens visited mankind with their horrid, irresistible power, scattering men to the stars. Dying and failing and sometimes prevailing, the pantropicly altered men of many new subspecies on the terraformed worlds now used the techniques pioneered by Montrose to create Pellucid, to stir their nickel-iron cores to life as Potentates; and those, in turn, took their fire giants, ice giants, and gas giant worlds within reach and, using the techniques pioneered by Del Azarchel, woke Powers to awareness; and those Powers, urged on in messages never heard by mortals by the dark agencies of Hyades, built Dyson clouds and Dyson spheres and macroscale structures in rings and hemispheres about their stars, gods beyond gods, self-aware arrays large as solar systems, called Principalities.

The chords and notes of the symphony of history changed, but the two great themes never ceased to clash: the urge for liberty, with each man free to calculate his own destiny and selecting his own place within the scheme of prediction, forever fought the need for unity, conformity, and, above all, predictability, without which long-term trade with Hyades was impossible.

The enmities between the Powers, who warped and bent the currents of predictive history to their dark will, were carried on in those children that so far surpassed them, as the gods in legend overtowered the titans: the Principalities of Tau Ceti, Proxima, Altair, and 61 Cyngi. A greater plateau of intellect, immeasurable, indescribable, unimaginable to biological life, was achieved, but not peace.

But Montrose, seeing that these convulsions and conflicts would not diminish the ability of civilization to decelerate and receive his approaching wife in her strange, huge, lonely vessel, kept his ageless vigil and slept through it all.

Throughout, Blackie seemed not to be doing anything sinister. What was he waiting for? What was he up to?

The nagging fear would not leave Montrose that his bargain with Blackie had been a mistake, and it all was going to explode in his face.

5. Duel to the Self-Destruction

But one of the remote Montroses, a man no smarter than Montrose had been back when he was only Mr. Hyde, a mere posthuman with an intelligence of four hundred, broke into the conversation path with a priority signal. “Worrying about Blackie is a fine hobby to keep a body busy while we wait. Beats whittling. But that is not the reason you keep waking yourself up.”

“So what’s the reason?” snapped Central Montrose.

Posthuman Montrose said, “We are still crippled by the limits of our own mental architecture. It don’t scale up. The superbrains, the bigger they get, the easier they get to go crazy, easier to divaricate, easier to split into a zillion stray thought-chains, each squabbling like snakes in a mason jar. That is why Jupiter killed his bad ol’ self, and don’t fool yourself none thinking otherwise. Lookit here, smarty-pants Montroses.”

An image came over the channel. Posthuman Montrose was dressed in a dark cloak and a wide-brimmed sombrero, standing near a grove of peach trees adorned with roses rather than peach blossoms. He was peering to where two men in armor stood in the near distance.

These were two more Montroses, both semiposthuman, each equal in body and mind, wearing the armor of duelists, each carrying the cubit-long iron tube of a Krupp dueling pistol.

They stood in a field of some species of bright red clover and pink grass Montrose did not recognize, some weed imported from another world, which should not have been able to grow on Earth. Behind them was a row of tall banners and standards of orange and gold whose meaning Montrose did not recognize, but a helpful familiarization file explained that these were privacy flags, attempting to emit encryption to ban the attention of media, gossips, and historians.

“I am here to kill myself?” Montrose muttered. “This is not a good sign.”

The judge was dressed in the distinctive garb of a Penitent, barefoot in a white robe and conical purple hood of unlikely height, with a rope for a belt.

The men of the planet Penance were similar in build and look to Rosicrucians, since they were all descended from the sons of Cazi who had aided Montrose in stealing his starship, the Emancipation, back from Blackie, star-faring toward what was an uninhabited planet when they set out, but arrived to find a starving colony of Swans and Men from Albino and Dust, dropped there by the inhuman indifference of the Fourth Sweep. The ancestors of the Penitents half saved and half conquered these survivors and built a mighty civilization where men were free and secure.

The world had worked and woken to self-awareness in record time and launched a gigantic treasure ship back to Sol to prove the point of what a free world could build, arriving in the Fifty-Sixth Millennium.

Ah! Montrose grinned at the memory, because the ship, christened the Prestor John, had been outfitted at his suggestion as a huge fraud, crewed only by female astronauts prettier than their Fox Maiden ancestors and pretending to be from the lost and legendary colony at Houristan, the paradise of women. For once, events worked out as Montrose’s secret calculations of cliometry predicted, and as the Guild grew fearful of an imaginary empire beyond their boundaries, and ashamed of the example, so the interstellar slave trade waned and was abolished in many ports of call.

The recollection warmed him like an ember in a pipe. After a trick like that, fooling even the Archangels and Potentates and Powers, what need had Montrose had to stay awake and look after things?

A familiarization file helpfully explained that a domed city called Penitentiary still rested on a mountain in Asia on Earth, holding the environment and oxygen-charged atmosphere of that remote world, and proud and wealthy descendants of the ship’s crew dwelled like their ancestors, and their daughters eagerly sought in marriage or for pageants and displays or events of less worthy sorts. By tradition, they hid their wealth, and walked abroad in humble garments, and were hated and envied nonetheless. Small wonder the duelists selected a man from that race to be their judge of honor.

The two Seconds assisting in the duel shocked him to see.

One was the rotund form of Mickey the Witch, whom all reports and all common sense said should have been dead countless centuries and millennia ago. His face was round and full of mirth, and his eyes were small and twinkled with cunning.

He was dressed in robes resplendent and lavish to the point of absurdity. Silks as black as raven’s wing and scarlet like the cardinal’s were trimmed with ermine whiter than the snowy owl. There were nine yards of cloth just in the sweeping sleeves whose hems trailed on the grass. His shoes had pointed toes so extravagantly long and tall Montrose wondered that they had impaled no passersby. And all this was adorned in gems and gewgaws and inscribed with trigrams and psalms and mystic circles and astrological signs from a dozen bogus systems of occultism. The tree of the cabala along the spine of his flowing alb was enhanced with sigils from the Monument. Most absurd of all was his hat, which was a cone a cubit high, with jeweled chinstrap and ceremonial earflap, tassels, scarves, homunculus mouth, blinking eyes, and brim of glittering moonstones.

The other Second was a girl, which was a shocking breach of tradition. Her body was perhaps eighteen, but from her stance and glance and tilt of her head, her mind was years younger. Her eyes were wide and wrapped in dreams, her lips pouty and pretty and ready for kisses, but her hair was an astonishing wilderness of purple that glowed with phosphorescence. She was naked except for a semitransparent, semiluminous garment flung casually over one shoulder that flowed and floated around her shapely limbs. It was a blue-gray material that seethed like a live thing, glinting with sparks of motion, like a nest of invisibly tiny numberless flying insects whose legs were so entangled to each other that the whole formed long, elegant sheets and pleats and folds.

He did not recognize her, but from the electromagnetic echoes around her head, his instruments detected that she had the directional sense of a migratory bird. She was a Sylph, a member of a race of airborne nomads so long dead that even Montrose’s advanced brain ached with fatigue when counting the ages gone.

“Who the plagued roup is that?” Central Montrose shouted.

Posthuman Montrose, standing at the edge of the red field in a black hat and poncho, said, “You are an idiot.”

An Archangel Montrose said, “That is Trey.”

“Who?”

“Trey Soaring Azurine, the Sylph. You met her the day you discovered Rania had ripped the diamond star out of orbit, and was lost to you for thirty-three thousand nine hundred years times two plus change; and that same day, Blackie put his handprint on the moon. She went into slumber, one of your first customers ever, just to follow you through time and see what happened, how it all turns out.”

“And why is Mickey here?” asked Central Montrose.

“For the wedding,” said Potentate Montrose, looming like a sphinx above the thoughtscape, this mind too deep and rapid to apprehend. “For love.”

“What wedding?” asked Central Montrose.

“You are an idiot, like our idiot brother said.” The Archangel Montrose sighed.

“Thanks, I think,” said the Posthuman Montrose. “Makes me want to shoot myself, sometimes.”

Central Montrose looked through Posthuman Montrose’s eyes by feeding a stepped-down neural flow from the posthuman into the optic centers of his brain. Now a large torpedo-shaped dirigible hanging just above the grove could be seen. It was a Sylph aeroscaphe, complete with serpentines dangling from its gondola to give it the aspect of a jellyfish. Montrose would have been just as surprised to see a gasoline-powered Ford Thunderbird from Detroit from the First Space Age or galleon from the Golden Age of Spain.

He looked at the girl’s wild eyes and her strangely absentminded smile. “I dunno. That girl looks a little … unstable. Didn’t she get shot in the gut or something? Wasn’t she going to marry Scipio?”

The Posthuman standing on the field said, “It gets better.” He stepped out from the rose-covered trees and directed his eyes to another point of the field. To one side, beyond the banners but near the rose trees, sat Del Azarchel in a Morris chair, eating popcorn from a paper bag, perhaps the only paper bag on Earth in this era. His smile was like the sun. He had waxed his moustache and combed his beard, and looked more like a goat than ever, or perhaps like some pagan god of old who danced in the wood and worked malice on unwary Greeks.

“Bugger me with a submarine! What the pestiferous epidemical plagues of hell is that whoreson coxcomb doing here?”

“Gloating,” said the Posthuman. “Want me to go over and talk to him?”

“He is poxy up to something! He has got some scheme! What is he up to?”

The Archangel spoke again. “Off and on—and more off than on, due to energy budget constraints—we been watching him over the centuries, or having our Patricians do it, or Neptune.”

“So what is he plaguing up to?”

“Your lesser version just told you, you stump-stupid, pox-brained buffalo. Gloating. That is what he is up to. He is watching us tear ourselves apart the closer she gets to coming home. Show him the last bit, little brother.”

The Posthuman turned his head.

Opposite him, on the other side of the field, stood Rania dressed in a simple robe of white, her bright hair and brighter smile and eyes like an angel. The sight of her face was like twin daggers of light in through his eyes into the deepest part of his brain. The pain and longing and love choked his next thought.

But Posthuman Montrose said, “That’s not her.”

Central Montrose said, “What the pestilent pox is going on?”

“Turns out that there was some leftover false Ranias,” Archangel Montrose explained, “made by our old pal Sarmento ‘Makes Me Ill’ a d’Or, or maybe from those experiments our friend Mother Selene halted, way back when.”

The Posthuman said, “The lady is a Monument reader. She got found in one of our old, old tombs and woken up by some man or some god with nothing better to do. Half a century ago our time, the first message from the Solitudines Vastae Caelorum was picked up by ultrasensitive receivers—”

“—that is the human name for the attotechnology supership the aliens at M3 gave the real Rania. What the aliens call the ship, we don’t know. The message is called the Canes Venatici Neutrino Anomaly—” supplied the Archangel Montrose, interrupting on a parallel channel.

“—and Number Six over yonder wanted to go through the Monument notations Rania sent line by line, and got this girl to translate for him, and spent too much time alone with her, and sniffed what she smelled like, and saw that place behind her ear when she turned her head, and sure looked like Rania’s neck, white as a swan’s neck and all, and so he done fell empty head over kicking heels in damnable love with her. Her name is Shiranui Kage-no-Ranuya-ko, the fiery shadow of little Rania.”

It was the name of a Fox Maiden, a race long ago extinct on Earth, which meant she had come from a deeply buried tomb, or from the Empyrean.

“What’s the fight over?”

“Number Five, that’s our cousin there, says the only way to keep every version of Montrose willing and able to recombine into one person with one mind and one soul is if and only if we all have one purpose. Love for Rania. So Six says no, this is an exception, and Five says bullpox, and Six says up your nose, and Five throws down the glove and says get your Seconds and your shooting iron. Got it?”

Angrily, Central Montrose sent, “There was a message from Rania, and you did not wake me?”

The Posthuman sent back, “You should word your orders more careful-like. The message, it didn’t have nothing personal in it, just cliometry equations to pull mankind back from the brink of extinction, so we did not wake you up.”

Central Montrose said, “She would have put in a secret message just for me, hidden in the enjambments and negative thought-character spaces!”

The Posthuman said, “We looked. Weren’t nothing. So we let you snooze. You wanted to slumber so damn much and just get the waiting over, right? And everything was all set, right?”

The Archangel added sardonically, “Besides, waking all us up at once, much less fitting every memory and personality growth back together into one system in one body costs money, and unless someone wants to pay me to do a historical essay starring my pox-awfully wondrous wonderful self, what skills we got this market here and now cares diddly-do about, eh?”

The sheer sass of the reply was a bad sign. Usually he was more respectful of himself. He looked at the numbers in his mind’s eye, ran through the cliometric calculus, and got a nonsense answer. Some factor was missing from the equation.

“I don’t know. Blackie never seems to run low on funds.”

“Well, you’re supposed to know,” said one of him. (He was not sure which one. All of him sounded alike to him. He wondered if his other hims had the same problem.) “You! You are the central leadership node of our scattered personality here. You’re the boss.”

“Well, pox on you and the rutting donkey that you rode in on! You are the current version, who is supposed to keep an eye on events—and an eye on Blackie—and wake me when something needs fixing so I can sleep in peace!”

The Archangel chimed in, “Little brother, I ain’t even sure how the market works these days, and I have an intelligence range north of ten thousand.”

“I ain’t as smart as either of you, but I read the day feeds,” said the Posthuman. “It is a system that tracks a quantified form of liquid glory the Patricians drink and bathe in.”

“What the hellific pox? Do you mean glory like bright light, or glory like the applause of the world at your reputation?” asked Central Montrose.

“Both and neither,” answered the Archangel and Posthuman together. Those two had knit themselves back into a single system at this point. The debt register showed considerable expense just for those two to merge. “Don’t worry. The Fox Maidens and the Myrmidons, back when they still existed, could not make heads nor buffalos about it neither.”

The Potentate from the world’s core said, “This problem is insoluble. If we sleep, we miss life and snore through dangers. If we wake, we change too much, and Rania won’t know us. You have slept too long, and the signs of disunion and disharmony you see among the lesser versions of us is a by-product of Divarication.”

But one of the duelists, Number Five, sent angrily, “It’s not Divarication. It’s madness. Your conscience is lashing you like Mom used to. That clench in your stomach is you trying not to puke up what you swallow of your bad deeds. And now Rania is getting close, and it is getting too late!”

Central Montrose sent, “What bad deeds?”

“Giving up on the human race. You don’t care what happens once Rania comes back!”

Central Montrose had no reply to that, but he could feel segments of his mind rapidly trying to rewrite the thought, distort it, hide it from himself, and that made him sickly suspicious that Number Five Montrose was right. So he said nothing.

Number Five said, “You won every fight, even against artificial minds orders of magnitude smarter than you, because of one thing. They thought in the short term, the length of their lives, the life of their clan or their civilization, but no longer. You thought in evolutionary life spans, in the scale of geologic ages.”

“Because the only damn thing I gave a damn about was geologic ages away from me,” muttered Montrose. Several Montroses on the line muttered agreement.

“But now you’ve brought your eyes away from the horizon to the foreground. You are looking at tomorrow, when Rania comes, but not what happens the day after tomorrow.”

“Why the poxing pox should I give a tinker’s damn about that? Let the day after tomorrow pox itself for all I care.”

“But she will care, won’t she?”

Central Montrose sent, “If you are less smart than me by a zillion points of intelligence, and the Archangels and Potentates are smarter again by another zillion, how come you see this plain and none of us smarter than you sees it?”

“’Cause smarts ain’t everything. Brains is most things, but not everything. I got a simple brain, a posthuman brain, and my little balloon of a mind is so small that the volume is clear compared to the surface and the light shines all the way through. You guys have more brainpower to monkey yourselves up with lies and brain-lard. Well, snap out of it.”

“Snap out of what? I am about to shoot myself out there. Put away your piece, you maniac!”

“I got to kill all parts of me that don’t love Rania,” said Number Five grimly. And suddenly the channel went dead.

6. The Second Second

So there it was: a hard, cold certainty in himself that Number Six deserved to die for rutting with a Fox dressed up to look like Rania. He could think of nothing more viscerally disgusting, more worthy of death by gunfire. He did not want to recombine back into himself any memory-chains containing the memories of whatever thoughts or temptations or justifications he had used on himself to excuse adultery. It was an absolute in his soul: there was no debate, no second thoughts.

So, without thought, he combined himself with Number Five. It used up nearly all the credit in his account. By the time he raised his pistol and armed his countermeasures, there were two of him in the nervous system, pulling the trigger together. By the time he lowered the massive weapon and stepped heavily forward from the octopus-armed black smogbank of chaff and looked down at his dead opponent, he was one.

Melechemoshemyazanagual Onmyoji de Concepcion of Williamsburg hailed from the Fifth Millennium, an Era of the Witches during the ten-thousand-year period known as the Hermetic Millennia, in the long-forgotten years before the First Sweep, when mankind was merely the experimental plaything of Blackie del Azarchel and his fellow mutineers who survived the Hermetic expedition. His true name was Mictlanagualzin, but Montrose called him Mickey.

Now Mickey waddled over to help Montrose out of his armor, while the Penitent judge gave an abrupt gesture to a grave-digging automaton carrying a coffin and a shovel. The machine groaned and stepped forward and shoved the blade of its shovel into the soil.

“Mickey, what the pox are you doing here, acting as my Second?” When the helmet hiding the face of Montrose came off, Mickey stepped back, raising his hand before his eyes. He could not meet Montrose’s gaze.

“Ah!” said Mickey. “You have torn your soul in scraps, and now a larger fragment descends like a bat from the infosphere to possess you! Did I not warn you in ages past to have no traffic with the Machine? Now you are one.” He shook his head sadly, and his jowls wobbled. “Alas! I hope you got a good price. I envy you. No more soul-selling for me.”

“You didn’t phlegming answer my question.”

“It is not necessary to answer the gods, even ones, like you, who are insane and think they are not gods. Your mind is suffering from an

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...