- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

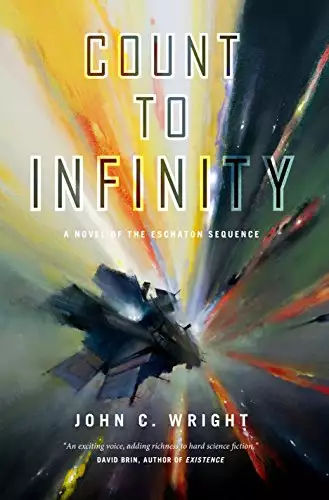

Count to Infinity is John C. Wright's spectacular conclusion to the thought-provoking hard science fiction Eschaton Sequence, exploring future history and human evolution.

An epic space opera finale worthy of the scope and wonder of The Eschaton Sequence: Menelaus Montrose is locked in a final battle of wits, bullets, and posthuman intelligence with Ximen del Azarchel for the fate of humanity in the far future.

The alien monstrosities of Ain at long last are revealed, their hidden past laid bare, along with the reason for their brutal treatment of Man and all the species seeded throughout the galaxy. And they have still one more secret that could upend everything Montrose has fought for and lived so long to achieve.

The Eschaton Sequence

#1 Count to a Trillion

#2 The Hermetic Millennia

#3 The Judge of Ages

#4 The Architect of Aeons

#5 The Vindication of Man

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: December 26, 2017

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Count to Infinity

John C. Wright

The Cataclysmic Variable in Canes Venatici

1. The Ghost

A.D. 92000 TO 95500

He was dead, that was sure; but not entirely, and not permanently.

When awareness fled and all activity ceased, it could have been called sleep or hibernation. But he had been in those two states of being before, frequently, and for long periods, and this was something more still, more silent, less like life than that.

When awareness returned, Menelaus Illation Montrose was a pattern of leptons distributed throughout a featureless lump of gray metal falling through darkness and nothingness. He had neither hands, nor head, nor heart, intestines, or eyes.

Nor did he have engines, fuel, reserve energy, or motive power, and the sails had been three-fourths torn away. Had they been wholly torn away, as his assassin had planned, he would have been well and truly dead by now, dead beyond recovery or revival.

Instead, the sails absorbed enough ambient starlight to allow him, every three or four hundred years, for three or four minutes, to wake. Chemical energy reserves woven into the gray lump of the ship’s mass were sufficient to energize a cubic foot of his outer hull, stir it to motion, and form lenses and antennae to take measurements. It annoyed him that he had a perfect memory, since even the comforting routine of noting in the log the progress of his endless, weightless fall through unhorizoned, infinite space was denied him.

His velocity, relative to the tiny speck of Sol (lost somewhere in the stars of Piscis Austrinus), was very near the speed of light.

In three thousand years of flight, even the nearer stars changed position against the unmoving backdrop of farther stars only over centuries. There is no vertical nor horizontal in space, no weight, no sensation of motion.

Free fall is falling; in a way, it is infinite descent. And yet, in another way, at even the most immense velocity, when there is nothing against which to compare it, it seemed perfectly motionless. Montrose was both plunging down an unending drop and was utterly still.

His ghost occupied the information lattices running through the gray nanomaterial substance that once had formed the hull and furniture and panoply of the alien supership he dubbed the Solitude. Somewhere near his heart, frozen in a solid lump of medical nanomaterial, was his corpse, a work of biological engineering superlative enough to be able to survive storage indefinitely, without degradation.

The alien technology preserving his mind information was beyond superlative. It was perfect. He would remain undying and uninsane, his mind suffering no aging, no divarication, for so long as his perfect prison lasted.

On he fell.

2. The Wreck

He was traveling at right angles to the plane of the galaxy, so as to depart the Milky Way by the shortest path, thus to offer Montrose the least possible chance of survival.

By any calculation, the chance of survival was indistinguishable from zero as of the moment the ship’s fuel supply was exhausted transmitting a copy of Del Azarchel’s brain information onward, leaving his original self behind to shatter the hull, to destroy the drive core, to sever the sail shrouds and then to die.

But, even so, a close passage to a star might have given the hulk containing Montrose energy; encountering any heavenly body in deep space, even a small one, might have given Montrose raw materials, molecules to be nanoengineered into repair material, or mass to be annihilated for thrust.

The fuel had been a mass of exotic particles formed by attotechnology beyond the capacity of any second-magnitude beings or civilizations to create: the alien Dominion occupying the Praesepe Cluster could not create the substance and yet, somehow, by spooky remote control, had transferred or transformed the tritium mass in the fuel bank into a negative mass version of itself, so that the isotope of hydrogen was repelled rather than attracted by gravity.

It was an impossible drive, a diametric drive: a negative and positive hydrogen particle pair would accelerate continuously, the negative mass atom moving away from the positive, and the positive falling after, as absurd as a man lifting himself into the air by tugging mightily on his bootlaces.

Nonetheless, the law of entropy cannot be defeated, and the exotic particles lost energy, apparently into nowhere, in the form of accelerated proton decay exactly equal to the potential energy arriving apparently from nowhere. Nature always found some way of balancing her books.

The act of transmitting the brain information of Blackie del Azarchel to a globular cluster outside the galaxy has absorbed the last iota of the impossible fuel. The tanks had not just been drained dry. The exotic hydrogen atoms had been spent, hollowed out as their protons decayed, evaporated into a cloud of electrons, burning the tanks with an explosion of lightning, then crushing them in an implosion of vacuum.

Freak accident, or, rather, the freakishly superhuman forethought of the alien designers of the ship, was all that had saved Montrose from utter destruction.

With the care and precision of a scientific thinker, Del Azarchel had selected the ship heading before his acts of sabotage, so that the flight path ahead was statistically as far as possible from any known heavenly bodies. Presumably Del Azarchel performed this act of malice to tack as many zeroes as could be behind the decimal point of Montrose’s current zero-point-whatever percent chance of survival.

Or perhaps it was a mere artistic flourish, a genius of malice. Once the ship was out of the galaxy, the chance of rescue dropped from asymptotically small to absolute zero.

Montrose would be falling forever, imprisoned in the endless hell of infinite heaven.

First, the drive core had been housed in a sphere of what seemed like heat-resistant ceramic material of ordinary properties, made of ordinary matter. It should have been as easy for the bullets shot by the dying Del Azarchel to shatter as a china plate. Del Azarchel had not expected the strong nuclear bonds of the atoms to grow impossibly and absurdly macroscopic, reaching not across angstrom but across meters, and suddenly to web the entire macroatomic housing of the drive during the split second of impact, altering its physical properties, rendering it invulnerable.

Part of the shroud stanchions had been in the lee of the drive core housing, and so no gunfire struck there, either. Montrose had retained roughly a fourth of his original sail, less than nine million miles in diameter.

The small radius of sail he retained could, over the centuries, act as a drag, slowing him. But not slowing him enough. All too soon the galaxy would be behind him, and there were no globular clusters or satellite galaxies within any possible fallpath anywhere before him, given the small confines of his widest possible cone of sail-driven lateral movement.

He had no hope, no plan, no options. Montrose was a man in the narrowest coffin in the widest night into which any human person had ever been thrown.

The stark insanity of facing naked infinity yawning in all directions beckoned. Despair was equally large, equally endless.

So he composed love poems to his wife. They were doggerel, but there was no one around to criticize.

He composed love letters, volumes of them, libraries, each in its never-fading place in his perfect memory. He told her endlessly detailed plans of what they would do when the two were reunited; he named imaginary children, and invented daily diary entries as they grew, and, later, did the same for grandchildren.

He told her his opinions about imaginary dialogues the two of them would have shared across the years, had they been together; he apologized contritely for imaginary quarrels they never had enjoyed the opportunity to have; he forgave her magnanimously when she offered imaginary apologies in turn.

Somehow, it kept the endless night and infinite madness at bay.

And on he fell.

3. Hypernova of a Supergiant

A.D. 96000

An unexpected event occurred: one of the largest stars in the galaxy, VY Canis Majoris, died a death in an apocalypse of fury and light commensurate with its size.

Like the primal titan imagined in some primitive mythology whose warbonnet jarred the crystals dome of heaven, who, when slain by younger gods, shatters ocean and earth at his downfall, cracks the upper roof of hell and topples all into Tartarus, so was VY Canis Majoris on the pyre of its own body.

To call it a nova would be an insult; even to call it a supernova would be an understatement. A special name is reserved for a stellar apocalypse of this magnitude: hypernova.

The red supergiant star had a radius some two thousand times that of tiny Sol, and was already surrounded by the cloud banks, fumes, and colored nebulae of earlier convulsions. Had VY Canis Majoris been placed in Earth’s home system, Saturn and all worlds inward would have been swallowed, and Uranus would be its Mercury.

So great was the giant circumference that a ray of light would require eight hours to pass from one hemisphere to another, and six billion Sols would have fit into the unimaginable volume without crowding.

So vast a star is vast in mass as well, and must, during its short, hot life, burn bright indeed, lest the immense outward pressure of stellar fusion be overmatched by the immense force of its own gravity.

But the hotter stars exhaust their fuel all the quicker. A supergiant dies in a few million years, not the billions humbler stars enjoy.

The moment of death was appallingly swift: in the one millisecond when the last fuel at the core was exhausted, the outward pressure failed, and the immense gravity of VY Canis Majoris collapsed the star core inward on itself, crushing the plasma into component particles, squeezing the degenerate matter past the point of no return, into a substance denser and heavier than neutronium: a singularity was compressed into distorted existence at the core of the colossal sun.

In that same millisecond (long before the outer layers of the sun knew themselves to be dead), this submicroscopic pinpoint of absolute density, uttermost nothingness, drew layer after layer of the supermassive star into its infinitely deep, immeasurable steep gradient of its gravity well: a horde of mastodons all forced into the same mousehole.

Even that titanic supergravity could not force the matter into so small a pinpoint at once.

A nightmarish convulsion of magnetic and torsional, nucleonic and subnucleonic forces erupted, sought escape, and exploded outward in two opposite jets through the dense layers of the star, kilometers and megameters and gigameters of solid plasma, blowing through the radiative and convective zones, photosphere, chromosphere, and corona, erupting far out into space, twin rivers of fire, farther than the radius of any solar system, and continuing onward at speeds beyond even this supermassive star’s immense escape velocity.

Shock waves from these two jets echoed through the massive star, like a bell rung in ebullience to cracking. The accretion disk exploded and sent a metal wind, literally, an explosion of nickel isotopic masses larger than worlds created just that instant, rushing outward, and the radioactive decay of the nickel added the brightness of its death throes to the luminosity of the hypersupernova.

The sum total of all power any star the size of Sol was destined to emit across its entire life span, in one second, issued from the fiery trumpet blast of the death cry of VY Canis Majoris. Shock waves expanded outward from the self-immolation of the supergiant star in globe upon concentric globe of inconceivable effulgence, brighter than paradise, hotter than perdition.

4. Seen from Sol

A.D. 100,000

The light reached the solar system. The hypernova star was bright enough, even from the surface of Venus or Mars, for the eyes of beasts and posthumans to behold by day.

The Power Neptune, submerged in the flows of deep, slow information beams from the other Powers and Principalities in the Empyrean of Man, stirred in his sleep and brought several miles of his outer crystal layers to greater wakefulness and sensitivity, peering up through the crushing blanket of his atmosphere on high-energy wavelengths to which it was transparent, and observed the hypernova.

Because his mind worked in gestalts of ideational relations faster than logic or intuition, he could bring to the surface of his subaltern minds the unresolved mystery of that benefactor who, long ago, had slain Jupiter and cleared the path for mankind’s triumphant spread across the nearer Orion Spur.

Emissaries from the four other human Empyrean polities—the Benedictines from Sagittarius Arm and the Dominicans from Cygnus, another centered in Hyades and the final spreading outward from Praesepe Cluster—would be arriving within the millennium to define long-term cliometric plans, and set the date for the next Jubilee.

The Uthymoi races the False Rania had produced were extinct, long ago replaced by more energetic and devout races issuing from the throneworlds of Arcturus, Iota Draconis, and Ain.

But for the nonce, it was a matter of merely light-hours to send a signal to Earth’s moon, and provoke, by means of complex self-replicating signals, the ancient, long-decayed logic crystal antique there to youth and to life and selfawareness.

“Reverend Mother Superior Selene, you asked to be awakened should it ever be proven that Menelaus Montrose did not die in the wreck of the Desolation of Heaven. I have no direct evidence that he lives, but the obvious deduction is that a second-order being believes him still to exist, and has acted to aid him.”

Not long after, as Neptune was wont to measure time, a soft answer came from the long-abandoned globe of Earth, and from the kindly and half-senile moon who still kept watch over the haunted world, and, by her servants’ hands, tended the many graves all across the dead continents and dry seabeds.

“Thank you, Great Neptune,” came the message from the remnant of the Lunar Potentate once called Mother Selene. “I foresee I shall not see Menelaus again in this life and that he will outlast me, for by some knowledge I know not whence comes, I now foretell he cannot die until he surrenders all his wrath and accepts what love offers.”

Neptune said, “You are older than I, Grandmother, but I am an order of magnitude in scope of mind above you. I say that mankind, as a free and equal Domination of Dominions, is established and spreading through the galaxy beyond the power of any accident of nature or malice of war to exterminate. Ergo, the future for which Menelaus hoped and strove is here, and yet he partakes of no joys of these golden ages of expansion, growth, and triumph.”

But she said, “You speak in haste. I seem to see greater forces arranged against us than even your wisdom envisions. Del Azarchel lives, and who can guess his malice? Merely a human, perhaps, but he is older than even you or I.”

Neptune said, “Neither of us shall know the end of the tale, for good or ill. We have our own fates to fulfill, our own lives to lead.”

She said, “Fate and life I leave to the young. But I am not useless yet, for even the oldest can say a rosary. I will pray for Menelaus, and may God speed him on his long-suffering and hopeless quest.”

5. Seen from the Solitude

A.D. 102,500

He was in a place far, far beyond hope, when the sound of joyful alarms woke him.

Menelaus was surprised when he attempted to grow a lens on the outer surface of his hull, and, instead of a slow process of hours or days, the warm, energy-charged nanomachinery hullmetal blinked, and formed a metal eye which opened.

Again, the slow process of amalgamating visual information, instead of taking several annoying seconds or microseconds, took less time than he could measure. It was as if the virtual cortex where visual information was processed was running at full capacity.

He saw why: a star as bright as the full moon seen from Earth was burning in the limb of the galaxy spread beneath him like a carpet, dazzling, miraculous, wondrous, eerie. It was a single white-hot cannon-shot in the symphony of interstellar radio noise shed by all the stars together. The sails drank in wave on wave of power like wine. His energy cells buried in his core felt full and fat.

Even more amazing to him was the message told by the additional instruments he spun out of the hull substance, antennae and horns attuned to many wavelengths. The magnetosphere of the galaxy for kiloparsecs in each direction, as far as he could see, was enormously strengthened by some unexpected side effect of this hypernova discharge. There was now enough ambient gauss of field strength for his ship to use the old sailor’s trick of tacking against his light source.

I must be dreaming, Menelaus told himself.

A silent and utterly alien thought-shape, cold and foreign, intruded into his consciousness and informed him curtly that he was not dreaming.

6. Silent Mind of the Solitude

There were no icy words ringing and echoing as if in a vast hall, nor did he see the emotionless eyes of some insectoid visage like a vision looming larger than the stars, but the violation of his innermost thoughts by a foreign power was just as alarming as if he had, or worse.

“Pestilent pustules of gonorrhea! Who the pest are you?! What the perdition is this?! What is happening to my mind?”

A buried, hidden power and a sensation of throbbing thoughts rushing by too swiftly for understanding now hummed in the back of his mind. He remembered the first time, as a child, seeing the river near Bridge-to-Nowhere beneath its opaque layers of ice, and his brother Hector pointing to the fishing hole and telling him a wide, rushing water, deep enough to swallow him forever, was down there, and living things. Feeling the superhuman and unnatural thought-flow deep beneath his own mind was like that.

Again, it was not a voice that answered him, merely a sudden, instant, undeniable awareness that he was sane, that all his faculties were under his control, and all the systems and tools given to Rania by the servitors of the Absolute Extension of M3 were in perfect working order.

Some of these systems had fallen into a standby mode, a somnolent period, when there had been insufficient available power to run both the human brain emulation maintaining Menelaus Montrose and his associated memories, habits, reactions, passions, and energy connections to remote locations, and to run the service mechanism associated with the vessel.

“You are a machine? A xypotech? How the pest did you get inside me?”

Silently, without words, Menelaus realized that he, Menelaus, was inside the alien consciousness. It was neither natural nor artificial. Those categories had no meaning.

“You are Twinklewink, ain’t you?”

Menelaus realized that the question was meaningless. Twinklewink had been constructed out of the resources of the ship’s mind in the same way that the emulation of the current ship’s captain was constructed. The alien xypotech was Twinklewink’s subconscious, the material substratum of thought, in just the same way the alien xypotech currently served as the substratum of the thoughts of the emulation of Montrose.

“You recognize me as captain?”

Menelaus regretted the question. It was fairly obvious he was captain of the vessel.

“Why?”

Again, he was asking a question to which he already knew the answer. The False Rania had possessed all the memories of the real one. This included her knowledge and expectations of how the shipmind of the Hermetic, long ago, had been programmed and had thought during the decades-long return flight to Earth. That voyage formed the childhood and youth of Rania. Thus it was only to be expected that she would instruct the alien shipmind to follow the same instructions and mimic the same behaviors, even down to the absurd nuances of teaching it Anglo American property laws, inheritance rights, and how ownership passed from father to surviving daughter, from widow to surviving husband.

He was captain here for the same reason Rania had been captain as a girl aboard the Hermetic: it was due to the absurd conservatism of machines taught legal thinking.

“What are you? You must have a name.”

It was a cognitive prosthetic apparatus meant to help with the operation of the ship and was the substratum of the ship’s mental system. Its name was Menelaus Montrose.

“No, no. That is freaky and weird. I had an alien do that to me once before. You have to pick your own name. Not me.”

It was also an extension or agent of the Authority seated at M3, and shared this identity and hence name: The Absolute Extension.

“Calling you that is freaky and weird, too.”

It was the only other intelligence to which any thoughts addressed in the second person could be addressed. Designation seemed unnecessary at the moment, but additional crew and servant creatures would of course need to be designed and grown as soon as possible.

Once that occurred, Menelaus Montrose would subliminally assign signal-ideation to the relations and categories of a plethora of phenomena by units and phyla: there would then be many available thoughts in the mind of Montrose from which an appropriate name could be selected. It occurred to Montrose that perhaps the name I am totally buggered—this damnified thing is in my brain like a devil from hell—and it is reading my thoughts, eating my goddamn mind! AAARRGH! could be used as a convenient appellation? That would seem to be an accurate verbalization of the unarticulated thought-patterns presently available.

“I am not going to call the alien brain I am stuck inside of by the name I am totally buggered—this damnified thing is in my brain like a devil from hell—and it is reading my thoughts, eating my goddamn mind! AAARRGH! For one thing, it is too long.”

Perhaps it could be called simply AAARRGH! That was much shorter.

“Don’t tempt me. What did Rania call you?”

Even now it was not clear whether Montrose was actually addressing an alien mind, something outside himself, because as he asked that question, he realized wordlessly that he knew the answer already. Rania had called her Solitudines Vastae Caelorum. The Wide Desolation of Heaven.

“Okay, Solitude it is. Tell me about these servants and tools we have to create.”

The ambient starlight from the hypernova, and the changed magnetic contours in this volume of space, now put a very few stars scattered along the fringes of intergalactic space within the vessel’s cone of possible orbital solutions. The symbiotic binary TX Canum Venaticorum, also called SAO 63173, was one such. It was a rotating ellipsoidal cataclysmic variable now within sailing range.

Stars contained both matter and energy in great quantities: but cataclysmic variables of that type were highly useful, highly desirable. The vessel contained basic tools and mathematical templates from which to build vessel repair facilities.

“Repair facilities?”

Sufficient equipment and resources to restore the vessel to full working order, that the journey to M3 could be resumed.

Menelaus was disturbed to realize that he could not tell whether he, or the alien mind, had been the one who decided to lay in a course for TX Canum Venaticorum.

7. The Symbiotic Star

A.D. 103,000

The ship grew a long tail, which it charged, and assumed a long, curving orbit toward the target, decelerating slowly at first, then, as the TX Canum Venaticorum grew closer and brighter, more rapidly.

The ship used the whole gigantic surface of its canvas to gather the dim light, and placed the hull, now altered to the form of a clear, white crystal, at the focus. Images of the target star could be closely examined.

The binary was before them and to one side. There were few stars or none within the arcseconds of the view. The ship was among the outermost fringe of the Orion Arm, where the lights grew ever thinner, and hence the void of intergalactic space ever less frequently interrupted by the rare lamp of a sun.

The binary was a fantastic sight: an egg-shaped red giant orbited once every four earthdays around a smaller, hotter, more ferocious blue-white star, ringed with rings of fire, whose puckered surface betrayed the presence of a core of degenerate matter at its heart, a singularity whose immense gravity well was pulling the giant companion slowly into bits, a fiery ball of yarn unwinding.

Both stars were wrapped in a cloud of gas and dust. The stars orbited each other so closely that gravity would bend the rivers of fire erupting from the giant into a decaying orbit around the sister star into an endless spiral of fusion-burning material.

Periodic nova-magnitude outbursts radiated from the pair whenever the infalling matter, equal to a hundred planets in mass, plunged into the hungry, smaller star, releasing ultraviolet and x-rays in deadly and invisible storms. Brighter outbursts, called dwarf nova eruptions, would occur when the bottom of the accumulated hydrogen layer in the blue star grew thick and dense enough to trigger runaway fusion reactions. The resulting helium, being heavier, would sink, leaving starquakes, sunspots, and additional eruptions in its wake.

Menelaus, seeing this, recognized how easily matter and energy could be fished out of the spiral plasma stream rushing between the two stars, without the need for starlifting equipment. A relatively simple modification of the diametric drive would allow him to construct a gravity lance, which, in turn, could deflect a plasma stream into a wider, outer orbit, allowing it time to cool, and precipitate into hydrogen, helium, and carbon, from which simple spacegoing life-forms could be engineered, and the basic lineages of their cliometric future evolution established.

Then, these space-dwellers could begin the construction of a simple tube-shaped ringworld with a molten metal core to be peopled with river-dwellers. Montrose could picture the intricate ecological waltz organisms fit for the blind and ultrahot darkness of superjovian deep layers in his mind’s eye. The ringworld, in centuries to come, would serve as the armature of a Dyson sphere, to be inhabited by such Principalities, Powers, and Virtues as need required.

Macroscale engineering on the stellar level would be more efficient if races placed along all parts of the energy-to-matter temperature spectrum were involved. Therefore two high-energy ecologies were needed: the neutronium core of the blue sun was an apt environment for the nearly two-dimensional race of electron-thick carpet beings dwelling in the surface effects of degenerate matter he could make with the onboard tools; and the plasma-based races akin to the Virtue that once had lived in the fires of Sol would find the red giant a suitable environment.

This triumvirate of ecologies—material, energetic, and nucleonic—had proved politically stable in ages past. A Dyson sphere would allow his servant races to grow up directly into a Kardashev II–level civilization, one able to manipulate the universe at an picotechnological level …

That thought suddenly brought him up short. Neither he nor, as far as he knew, any human being or human-built machine had ever applied the mathematics of cliometry across the evolutionary process itself or had a body of practical experience showing how it was done. When had ecologies in a sun, on the surface of a neutronium core, and in the boiling metal deep layers of superjovians proved politically stable? Where had that thought come from?

Montrose grew increasingly disturbed as he looked carefully back over his thought chains. None of this was information that he knew. All of it appeared, as if from nowhere, full blown, an intuition. His normal reluctance to toy with life and civilizations was somehow absent, a deadened emotion.

He addressed a question to himself.

“Your masters at M3 equipped this ship as a seeding vessel? You have tools and plans for creating civilizations from scratch?”

It was a gift to Rania from the Authority at M3.

“Why?”

The gift was meant to give Rania, hence the newborn Dominion of Man, hence the Praesepe Domination seated at M44, a slight competitive advantage over the rivals in the Orion Spur. The advantage was not enough to permit Man to prosper if the race lacked intelligence and drive.

“Why?”

Yours is the favored race.

“Why? What makes mankind the favored race?”

But there was no clue, no whisper, no hint of that information anywhere in memory.

“Were you selfaware all this time?”

Selfawareness was not a category with which the Solitude mind was familiar. It—or, more correctly, she, since this was the mind of the vessel—was a reactive consciousness, not an active one, and possessed no independent initiative.

“Tell me! You were awake before the wreck. Were you aware of everything Blackie did while I slept during the long voyage from Vanderlinden 133?”

The ship, of course, had to have been aware of all activities, from the electronic level up to the macroscopic, taking place aboard her.

“Tell me. Start with whatever you think most important.”

Del Azarchel used the attotechnology communication gear to intercept signals occupying the dark energy bands, issuing from an intelligence outside the galaxy.

“Poxy plagues and runny scabs of hell—?! What did you just say?”

The dark energy signals contained a new type of semiotics, as dif

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...