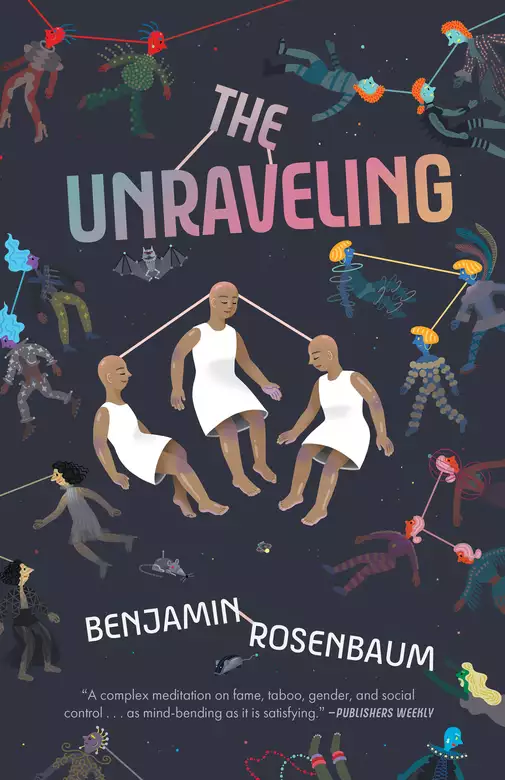

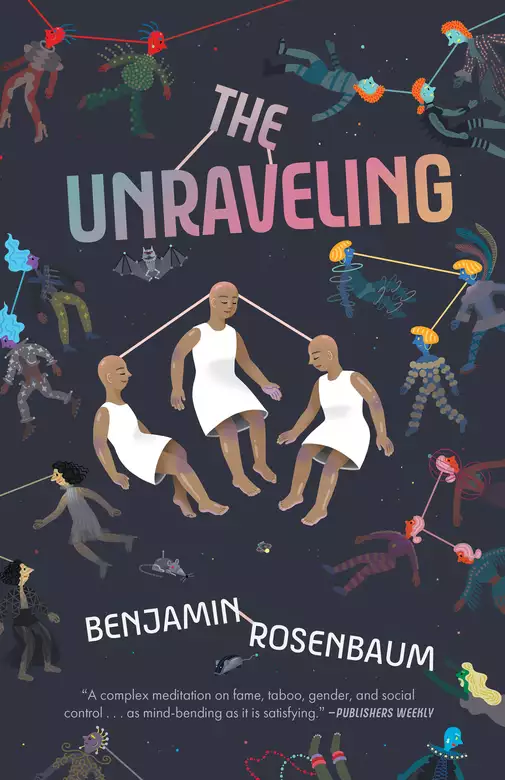

The Unraveling

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

“A wildly inventive, funny, and ultimately quite heartfelt novel, The Unraveling is a chaotic romp of gender deconstruction packaged up in a groovy science-fictional coming-of-age tale.” —Chicago Review of Books

In a society where biotechnology has revolutionized gender, young Fift must decide whether to conform or carve a new path.

In the distant future, somewhere in the galaxy, a world has evolved where each person has multiple bodies, cybernetics has abolished privacy, and individual and family success are reliant upon instantaneous evaluations of how well each member conforms to the rigid social system.

Young Fift is an only child of the Staid gender, struggling to maintain zir position in the system while developing a friendship with the acclaimed bioengineer Shria—a controversial and intriguing friendship, since Shria is Vail-gendered.

Soon Fift and Shria unintentionally wind up at the center of a scandalous art spectacle which turns into a multilayered Unraveling of society. Fift is torn between zir attraction to Shria and the safety of zir family, between staying true to zir feelings and social compliance . . . when zir personal crises suddenly take on global significance. What’s a young Staid to do when the whole world is watching?

Release date: June 8, 2021

Publisher: Erewhon Books

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Unraveling

Benjamin Rosenbaum

Fift was almost five, and it wasn’t like zir to be asleep in all of zir bodies. Ze wasn’t a baby anymore; ze was old enough for school, old enough to walk all alone across the habitation, down the spoke to the great and buzzing center of Foo. But ze had been wound up with excitement for days, practically dancing around the house. (Father Miskisk had laughed; Father Smistria had shooed zir out of the supper garden; Father Frill had taken zir to the bathing room to swim back and forth, back and forth, “to calm zir down!”) Just before supper ze’d finally collapsed, twice: in the atrium, and curled up on the tiered balcony. Father Arevio and Father Squell had carried zir, in those two bodies, back to zir room. Ze’d managed to stay awake in zir third body through most of supper, blinking hugely, breathing in through zir nose, and trying to sit up straight as waves of deep blue slumber from zir two sleeping brains washed through zir. By supper’s end, ze couldn’t stand up any longer, and Father Squell carried zir last body to bed.

Muddy dreams: of sitting on a wooden floor in a long hall . . . of zir name being called . . . of realizing ze hadn’t worn zir gowns after all, but was somehow—humiliatingly—dressed in Father Frill’s golden bells instead. The other children laughing at zir, and dizziness, and suddenly, surreally, the hall being full of flutterbyes, their translucent wings fluttering, their projection surfaces glittering . . .

Then someone was stroking Fift’s eyebrow, gently. Ze tried to nestle further down into the blankets, but the someone started gently pulling on zir earlobe. Ze opened zir eyes, and it was Father Squell.

“Good morning, little cubblehedge,” ve said. “You have a big day today.”

Father Squell was slim and rosy-skinned and smelled like soap and flowers. Fift crawled into Squell’s lap and flung zir arms around vem and pressed zir nose between vir bosoms. Ve was dressed in glittery red fabric, soft and slippery under Fift’s fingers.

Squell was bald, with coppery metal spikes extruding from the skin of vir scalp. Sometimes Father Frill teased vir about the spikes, which weren’t fashionable anymore; and sometimes that made Father Squell storm out of the room, because ve was a little vain. Father Squell had never been much of a fighter, the other Fathers said. But ve had a body in the asteroids, and that was something amazing.

Squell reached over, Fift still in vir lap, and started stroking the eyebrow of another of Fift’s bodies. Fift sneezed in that body, and then sneezed in the other two. That was funny, and ze started to giggle. Now ze was all awake.

“Up, little cubblehedge,” Squell said. “Up!”

Fift crawled out of bed, careful not to crawl over zirself. It always made zir a little restless to be all together, all three bodies in the same room. That wasn’t good; it was because zir somatic integration wasn’t totally successful, which is why ze kept having to see Pedagogical Expert Pnim Moralasic Foundelly of name registry Pneumatic Lance 12. Pedagogical Expert Pnim Moralasic Foundelly had put an awful nag agent in Fift’s mind, to tell zir to look zirself in the eye, and play in a coordinated manner, and do the exercises. It was nagging now, but Fift ignored it.

Ze looked under the bed for zir gowns. They weren’t there.

Fift closed zir eyes—ze wasn’t so good at using the feed with them open yet—and looked all over the house. The gowns weren’t in the balcony or the atrium or the small mat room or the breakfast room.

Fathers Arevio, Smistria, Frill, and another of Father Squell’s bodies were in the breakfast room, already eating. Father Miskisk was arguing with the kitchen.

{Where are my gowns?} Fift asked zir agents . . . but the agents didn’t say anything. Maybe ze was doing it wrong somehow.

“Father Squell,” ze said, opening zir eyes, “I can’t find my gowns, and my agents can’t either.”

“I composted your gowns. They were old,” Squell said. “Go down to the bathing room and get washed. I’ll make you some new clothes.”

Fift’s hearts began to pound. The gowns weren’t old; they only came out of the oven a week ago. “But I want those gowns,” ze said.

Squell opened the door. “You can’t have those gowns. Those gowns are compost. Bathing!” Ve snatched Fift up, one of zir bodies under vir arm, the wrist of another caught in vir other hand.

Fift was up in the air, wriggling, and was held by the arm, pulling against Squell’s grip, and was on zir hands and knees by the bed, looking desperately under it for zir gowns. “They weren’t old,” ze said, zir voice wavering.

“Fift,” Squell said, exasperated. “That’s enough. For Kumru’s sake, today of all days!” Ve dragged Fift, or as much of Fift as ve’d managed to get ahold of, out the door. Another of Squell’s bodies—this one with silvery spikes on its head—came hurrying down the hall.

“I want them back,” Fift said. Ze wouldn’t cry. Ze wasn’t a baby anymore; ze was a big staidchild, and Staids don’t cry. Ze wouldn’t cry. Ze wouldn’t even shout or emphasize. Today of all days, ze would stay calm and clear. Ze was still struggling a little in Squell’s arms, so Squell handed the struggling body off to vemself as ve came in the door.

“They are compost,” Squell said, reddening, in the body with the silver spikes, while the one with the copper spikes came into the room. “They have gone down the sluice and dissolved. Your gowns are now part of the nutrient flow. They could be anywhere in Fullbelly. They will probably be part of your breakfast next week!”

Fift gasped. Ze didn’t want to eat zir gowns. There was a cold lump in zir stomach.

Squell caught zir third body.

Father Miskisk came down the corridor doublebodied. Ve was bigger than Squell, broad-chested and square-jawed, with a mane of blood-red hair and sunset-orange skin traced all over with white squiggles. Miskisk was wearing dancing pants. Vir voice was deep and rumbly, and ve smelled warm, roasty, and oily. “Fift, little Fift,” ve said, “Come on, let’s zoom around. I’ll zoom you to the bathing room. Come jump up. Give zir here, Squell.”

“I want my gowns,” Fift said, in zir third body, as Squell dragged zir through the doorway.

“Here,” Squell said, trying to hand Fift’s other bodies to Miskisk. But Fift clung to Squell. Ze didn’t want to zoom right now. Zooming was fun, but too wild for this day, and too wild for someone who had lost zir gowns. The gowns were a pale blue, soft as clouds. They’d whispered around Fift’s legs when ze ran.

“Oh, Fift, please!” Squell said. “You must bathe, and you will not be late today! Today of all—”

“Is ze really ready for this, do you think?” Miskisk said, trying to pry Fift away from Squell, but flinching back from prying hard enough.

“Oh please, Misk,” Squell said. “Let’s not start that. Or not with me. Pip says—”

Father Smistria stuck vir head out the door of the studio. “Why are you two winding the child up?” ve barked. Ve was tall and haggard looking and had brilliant blue skin and a white beard worn in hundreds of tiny braids woven with little glittering mirrors and jewels. Ve was wearing a slick swirling combat suit that clung to vir skinny flat chest. Vir voice was higher than Father Miskisk’s, squeaky and gravelly at the same time. “This is going to be a disaster, if you give zir the impression that this is a day for racing about! Fift, you will stop this now!”

“Come on, Fift,” Miskisk said coaxingly.

“Put zir down,” Smistria said. “I cannot believe you are wrestling and flying about with a staidchild who in less than three hours—”

“Oh, give it a rest, Smi,” Miskisk said, sort of threateny. Ve turned away from Fift and Squell and towards Smistria. Smistria stepped fully out into the corridor, putting vir face next to Miskisk’s. It got like thunder between them, but Fift knew they wouldn’t hit each other. Grown-up Vails only hit each other on the mats. Still, ze hugged Squell closer—one body squished against vir soft chest, one body hugging Squell’s leg, one body pulling back through the doorway—squeezed all zir eyes shut, and dimmed the house feed so ze couldn’t see that way either.

Behind zir eyes Fift could only see the pale blue gowns. It was just like in zir dream! Ze’d lost zir gowns, and would have to go wearing bells like Father Frill! Ze shuddered. “I don’t want my gowns to be in the compost,” ze said, as reasonably as ze could manage.

“Oh, will you shut up about the gowns!” Squell said. “No one cares about your gowns!”

“That’s not true,” Miskisk boomed, shocked.

“It is true,” Smistria said, “and—”

Fift could feel a sob ballooning inside. Ze tried to hold it in, but it grew and grew and—

“Beloveds,” said Father Grobbard.

Fift opened zir eyes. Father Grobbard had come silently, singlebodied, up the corridor, to stand behind Squell. Ze was shorter than Miskisk and Smistria, the same height as Squell, but more solid: broad and flat like a stone. When Father Grobbard stood still, it looked like ze would never move again. Zir shift was plain and simple and white. Zir skin was a mottled creamy brown with the same fine golden fuzz of hair everywhere, even on top of zir head.

“Grobby!” Squell said. “We are trying to get zir ready, but it’s quite—”

“Well, it’s Grobbard’s show,” Smistria said. “It’s up to you and Pip today, Grobbard, isn’t it? So why don’t you get zir ready!?”

Grobbard held out zir hand. Fift swallowed, then slid down from Squell’s arms and went to take it.

“Grobbard,” Miskisk said, “are you sure Fift is ready for this? Is it really—”

“Yes,” Grobbard said. Then ze looked at Miskisk, zir face as calm as ever. Ze raised one eyebrow, just a little, then looked back at Fift’s other bodies. Ze held out zir other hand. Squell let go and Fift gathered zirself, holding one of Father Grobbard’s hands on one side, one on the other, and catching hold of the back of Grobbard’s shift. They went down to the bathing room.

“My gowns weren’t old,” Fift said, on the stairs. “They came out of the oven a week ago.”

“No, they weren’t old,” Grobbard said. “But they were blue. Blue is a Vail color, the color of the crashing, restless sea. You are a Staid, and today you will enter the First Gate of Logic. You couldn’t do that wearing blue gowns.”

“Oh,” Fift said.

Grobbard sat by the side of the bathing pool, zir hands in zir lap, zir legs in the water, while Fift scrubbed zirself soapy.

“Father Grobbard,” Fift said, “why are you a Father?”

“What do you mean?” Father Grobbard asked. “I am your Father, Fift. You are my child.”

“But why aren’t you a Mother? Mother Pip is a Mother, and ze’s—um, you’re both—”

Grobbard’s forehead wrinkled briefly, then it smoothed, and zir lips quirked in a tiny suggestion of a smile. “Aha, I see. Because you have only one Staid Father and the rest are Vails, you think that being a Father is a vailish thing to be? You think Fathers should be ‘ve’s and Mothers should be ‘ze’s?”

Fift stopped mid-scrub and frowned.

“What about your friends? Are all of your friends’ Mothers Staids? Are they all ‘ze’? Or are some of them ‘ve’?” Grobbard paused a moment; then, gently: “What about your friend Umlish Mnemu, of Mnathis cohort? Isn’t zir Mother a Vail?”

“Oh,” Fift said, and frowned again. “Well, what makes someone a Mother?”

“Your Mother carried you in zir womb, Fift. You grew inside zir belly, and you were born out of zir vagina, into the world. Some families don’t have children that way, so in some families all the parents are Fathers. But we are quite traditional. Indeed, we are all Kumruists, except for Father Thurm . . . and Kumruists believe that biological birth is sacred. So you have a Mother.”

Fift knew that, though it still seemed strange. Ze’d been inside Mother Pip for ten months. Singlebodied, because zir other two bodies hadn’t been fashioned yet. That was an eerie thought. Tiny, helpless, one-bodied, unbreathing, zir nut-sized heart drawing nutrients from Pip’s blood. “Why did Pip get to be my Mother?”

Now Grobbard was clearly smiling. “Have you ever tried to refuse your Mother Pip anything?”

Fift shook zir heads solemnly. “It doesn’t work. Ze’s always the Younger Sibling.” That meant the one who won the argument. But it also meant the littlest child, if there was more than one in a family. Fift wasn’t sure why it meant both those things.

Grobbard chuckled. “Yes. There was a little bit of debate, but I think we all knew Pip would prevail. Ze had a uterus and vagina enabled and made sure we all had penises for the impregnation. It was an exciting time.”

Fift pulled up the feed and looked up penises. They were for squirting sperm, which helped decide what the baby would be like. The egg could sort through all the sperm and pick the genes it wanted, but the parents had to publish something or other to get the genome approved, and after that it got too complicated. If someone got a penis they’d have one on each body, dangling between their legs. “Do you still have penises? One . . . on each body?”

“Yes, I kept mine,” Grobbard said. “They went well with the rest of me, and I don’t like too many changes.”

“Can I have penises?” ze said.

“I suppose, if you like,” Grobbard said. “But not today. Today you have something more important to do. And now I see that your Father has baked you new clothes. So rinse off, and let’s go upstairs.”

“Obviously I’m not talking about the details of the . . . process,” Father Smistria said, flinging vir arms wide.

“I should hope not,” Father Squell said. “Hold still, Fift!” Ve gripped Fift’s head firmly between one pair of hands and stooped over zir in another body to gently scrape away the last of zir hairs with the depilator. “It’s completely inappropriate to discuss it at all, Smistria. It’s a Staid matter, and that’s all there is—”

“I’m not discussing it,” Smistria said. Ve squirted oil onto vir palm and rubbed it into another of Fift’s scalps. “I certainly don’t want to know anything about what goes on in that room, for Kumru’s sake.”

“I should hope not!” Father Squell said.

Fift was in bright white shifts, like Father Grobbard always wore, and Mother Pip mostly did. All of zir was scrubbed and polished, one of zir heads was already shaved and oiled, and zir fingernails and toenails were trimmed. In the body that was already done, ze got up from the wiggly seating dome and wandered across the moss of the little atrium.

“Fift, don’t go anywhere, and don’t get dirty,” Father Squell said.

“But what does matter is the outcome,” Smistria said. “The outcome affects our entire cohort!”

Father Frill—lithe and dusky-skinned with a shock of stiff copper-colored hair sweeping up from vir broad forehead, wide gray eyes, a full mouth, and a sharp chin—swept into the room. “Kumru’s whiskers, Smi,” Frill said, “is that really what you’re wearing?”

“What’s wrong with it?” Father Smistria snapped, looking down at vemself. Ve’d changed out of vir combat suit into a tight sheath made of silvery blobs that flowed and split and swelled and shivered when ve moved.

As ze passed Fift’s waiting body, Father Frill bent down and ran a hand over zir bare oiled scalp (which felt nice, but also strange, like a layer had been stripped away and there was nothing between zir and the world). Frill wore cascades of gold, silver, and crimson bells that tinkled as ve moved. Vir martial shoulder sash hung with tiny, intricately worked ceremonial knives and grenades. “For one thing, Smi, it makes your potbelly look like a newly discovered high-albedo moon,” Frill said. “For another, it’s basically gray.”

“It’s silver!” Smistria shouted.

“Oh, please, you two,” Squell said, straightening up. Now all Fift’s heads were shaved. Squell closed the depilator. “Smistria, come on, just one more scalp to oil . . .”

“You take that back about the moon,” Smistria said, “or you’ll answer for it on the mats!”

“No doubt,” Frill said, “but not this morning, because we have somewhere to be. Seriously, Smi, are you thinking at all of what’s at stake here? I’ll do the oil, you go change. Into something colorful!”

Smistria stormed out and Fift followed vem in the two bodies that were ready. In zir third body, ze was still stuck in the atrium with Frill and Squell. Frill was massaging oil into zir scalp; vir hands were smaller and smoother than Smistria’s, and ve smelled like a sharp-toothed wild hunting animal from some forest far above them, up on the surface of the world.

“I’ll give vem a high-albedo moon,” Smistria muttered as they passed the supper garden. “Arevio! Do you know what time it is? Are you planning to attend this affair with your hands covered in dirt?”

Father Arevio, doublebodied, started guiltily up from vir plants. “Well, in fact, Smistria Ishteni, I was thinking of going singlebodied . . . I’m already dressed upstairs, and . . .”

“Oh no. Oh no. If I am going doublebodied to this . . . this void-blessed sit-about,” Smistria growled, “then by Kumru’s sainted balls you are doing the same.” Father Smistria only had two bodies, like Father Nupolo—all Fift’s other parents had three or four—and Smistria hated going anywhere in both of them.

Fift lingered by Smistria’s side in one body and went ahead down the hall in another. Back on the wiggly seating dome, ze dug zir toes in the moss, and Frill said, “Almost done, Fift. Don’t fidget.”

Father Arevio sighed, brushing off vir hands. “All right. I’ll change. I must admit, I am not terribly fond of these affairs.”

Smistria snorted. “Who is? We have to sit outside in the gallery, cooped up, gawking at each other’s outfits and taking offense—I swear, more mat challenges are issued at First Gates of Logic than any other time!—while they pass spoons and . . . well, whatever it is that they do in there . . .”

“It’s easy, Father Smistria,” Fift said. “All you have to do is . . .”

“Fift Brulio Iraxis!” Arevio said, coming forward.

“You stop right there, Fift!” Father Smistria said. “Do not say one word to us about the . . . about that.”

Fift swallowed. Ze must have looked scared because Father Arevio said gently, “it’s all right, Fift Brulio.”

“But it’s nothing bad,” Fift said.

“Of course it’s not bad,” Father Arevio said.

“Obviously!” Father Smistria said. “But you don’t talk about it with us.”

“Don’t let your Father Smistria worry you, Fiftling,” Father Frill said, in the little atrium, rubbing Fift’s head. “There’s nothing at all wrong with the Long Conversation.” Ve said the words with emphasis, like ve was showing that ve wasn’t embarrassed to say it out loud. “It’s very important. It’s at the heart of everything. And you’re going to be just fine. It’s just that Staid things are Staid things and Vail things are Vail things. You wouldn’t want to watch us fight on the mats, would you?”

“No.” Fift didn’t like the idea of zir parents angry and hitting. The mats sounded scary and strange. On the other hand . . . what if ze could sneak in and watch, with no one knowing? Just to see. Ze probably would. Still, ‘no’ was definitely the right answer.

“Well there you are,” Frill said. “It’s the same sort of thing.”

Arevio and Smistria went upstairs. Fift stood in the supper garden watching a golden cloud of spice-gnats hover around the vines and smelling their warm, cozy, tingly smell.

All it was going to be, this time, was sitting still and waiting to be passed a spoon, and saying “the spoon is in my hand,” and passing it on at the right moment, and telling the names of the twelve cycles, the twenty modes, and the eight corpuses. The Long Conversation. You couldn’t use agents to help with anything, but that was okay, because Pip and Grobbard never let zir practice with agents anyway.

In the body down the hall, ze poked zir head into the main anteroom.

Mother Pip was there, singlebodied, in a white shift like Fift’s, zir skin a deep forest green. Ze had stubby fingers that were usually relaxed, but right now they were tugging on zir thumb: tug, tug, tug. Ze had powerful, searching eyes that looked deep into you, white and gold and black. They were blazing. Fift wasn’t sure, but ze thought maybe Mother Pip was furious.

Fathers Miskisk and Nupolo and Frill and Squell were there, too. Nupolo was glaring. Squell was holding vir hands over vir mouth. Frill was throwing up vir hands in exasperation.

Father Miskisk was shouting. And pointing at Mother Pip. “It’s always Pip! Ze’s the Mother, ze guards our ratings, ze decides where we’ll live and when little Fift has to—has to—”

“Will you calm down, Misky?” Frill said. “Pip’s not going to be Mother twice over—even ze knows that would be too much! It will be Nupolo or Arevio, or Thurm if ve’d agree to it, or—well—” Ve tugged at one of the knives on vir sash as if waiting for someone to say “or Frill,” but no one did.

“If I may—” Pip began.

“Why are we talking about this?” Nupolo said. “On Fift’s big day? There’s no rush here. Ze’s not even five—”

Squell looked up, then, and saw Fift in the doorway. In the little atrium, where Frill had finished oiling zir last scalp and was rubbing vir hands with a towel, Squell said, “Come away from there, Fift. Come back in here, please.”

“This is the age when it matters!” Miskisk roared, tears streaming down vir face. “And what makes you think it will ever change? None of you will ever dare struggle with Pip over the maternity, and none of you have the strength to watch Fift be supplanted!”

Pip’s mouth tightened into a line.

“Fift,” Squell said, in the little atrium.

“Oh, for Kumru’s sake, Squell,” Frill said, in the little atrium, “just get zir out of there. Do I have to do it?”

Fift came out of the supper garden and into the hallway. Ze hesitated. Father Squell wanted zir to come back to the atrium, but ze looked down the hall at zirself, standing at the door to the main anteroom . . .

Miskisk was crying. Zir Vail Fathers cried all the time, but this was different. Vir limbs had loosened with sorrow and hopelessness; ve looked as if ve were going to collapse.

A chill raced down from Fift’s necks and settled in zir stomachs. Ze headed down the hall towards zir body watching Father Miskisk.

“It’s true!” Miskisk cried. “You’re too cowardly and too comfortable! You’d rather ze end up sisterless than endure the discomfort of zir supplanting!”

Sisterless was a bad word; Fift knew that much.

Fift caught up with zirself and came doublebodied into the anteroom. “Father Miskisk,” ze said, “do you want to zoom? We could zoom.”

Miskisk wailed, and Father Squell hurried across the room, picked up one of Fift’s bodies, and held out vir hand to the other. “No more zooming, cubblehedge. Come with me.”

Fift didn’t budge.

Squell picked up Fift in the little atrium, too, and said, “A little help, please, Frill?”

In the little atrium, Frill sighed. In the main anteroom, ve sighed again, crossed the floor, and scooped up Fift’s third body.

Father Smistria, dressed in an explosion of bladelike crimson and orange feathers, pushed past vem, going in.

“Smi, tell them!” Miskisk sobbed. “You agree with me! It’s too early for this—Pip can’t just—Fift deserves a little more time at home, to run and play and wear more colors than white, before—”

Smistria crossed vir arms. “Do I agree that Pip is bossy?” ve said. “And that everyone here is all too eager to postpone any argument, especially in the matter of Sibling Number Two? Certainly I do! But do I think you should be allowed to keep Fift here as a baby—dressed up in bangles and ‘zooming about’—to satisfy your selfish wish for a vailchild . . . ?”

Fift’s Fathers bustled zir up the stairs, doubly cuddled up against Squell’s soft soap-smelling skin and squashed into Frill’s bells, which tinkled around zir.

“Why is Father Miskisk upset?” Fift asked.

“Don’t worry about that, Fiftling,” Frill said. “You focus on what you need to do today.”

“Today of all days!” Squell said. “I can’t believe vem!”

“Am I going to be an Older Sibling?” Older Siblings were poor and pushed aside. Younger Siblings nestled in. But having a Younger Sibling also meant not being alone, having someone to protect and support, someone to share a childhood with. Fift had only ever been an Only Child. But there was something wrong, somehow, with being an Only Child.

Frill and Squell looked at each other over the tops of Fift’s heads and Fift could feel their bodies tighten.

“That’s enough of that topic, cubblehedge,” Squell said. “There are far too many thoughts jumping around in those heads of yours. We’re all just going to focus on what you have to do today, all right?”

{Why is it bad to be an Only Child?} Fift asked zir agents.

{That is not the polite term.} sent Fift’s social nuance agent. {You should say “an individual with an abundant-concentration-of-familial-resources childhood.”}

{What about sisterless?} Fift sent. Ze knew that word was bad, and ze shouldn’t say it, or even send it. But ze also knew it described zir. You’d rather ze end up sisterless . . .

{That is not a word we say.} sent the social nuance agent primly.

{Sister is an archaic word for sibling.} added the context advisory agent.

Fift closed all zir eyes and rummaged around among zir agents. The feed-navigational one could help zir find the main anteroom . . . and there it was. Ze could see it.

Miskisk had fallen to vir knees. “You are crushing my heart,” ve said, tears dripping from vir chin. “I have no voice here at all. It’s all zir cold dominion . . .” Ve gestured at Mother Pip.

“If I may,” Pip said, in a voice like ice.

“I cannot do this anymore,” Miskisk roared. “I cannot—”

“We have a pledge,” Nupolo said, in horror.

And then Frill and Squell and Fift were out of the apartment, through the front door, and up onto the surface of Foo. The inside of the house was swallowed into its privacy area, and Fift couldn’t see it anymore. Frill put Fift down, but Squell, doublebodied, held onto zir.

Above them was the glistening underside of Sisterine habitation: docking-spires and garden globes and flow-sluices arcing away. In front of them was the edge of Foo. Their neighborhood, Slow-as-Molasses, was at the end of one spoke of Foo’s great, slowly rotating wheel, and beyond it, this time of year, was a great empty vault of air . . . and then fluffy Ozinth and the below and beyond strewn with glittering bauble-habitations . . . and beyond that, habitation after habitation, bright and dim, smooth and spiky, shifting and still, all stretching away toward the curve of Fullbelly’s ceiling.

Father Grobbard was waiting for them on the path ahead where it meandered past a flowgarden.

{What’s a pledge?} Fift asked zir agents.

{A pledge is a promise that people make.} began the context advisory agent.

{But what do they mean?} Fift sent. {What pledge did my parents make?}

There was a lag, and when the context advisory agent replied, it sounded almost reluctant. {Your parents pledged to stay together for all twenty-two years of your First Childhood. To all sleep in the same apartment, once a month at the least; to attend family meetings; various such requirements. They had to. The neighborhood approval ratings for your birth weren’t high enough otherwise.}

{But this is not at all unusual.} the social nuance agent sent. {You shouldn’t worry.}

“Let’s get started walking, shall we?” Grobbard said. “You have a big day ahead; we might as well be early. The others will catch up.”

“But what about Father Miskisk?” Fift said. “Father Miskisk is sad—”

Grobbard laid a gentle hand on Fift’s shoulder, and Fift remembered that outside their apartment, they weren’t on the house feed. They were on the world’s feed, and anyone in the world could see and hear them.

“They’ll catch up, Fift,” Father Grobbard said again. “Clear your mind, please, and get ready.” They started walking, following the path among the gardens and gazebos of Slow-as-Molasses: Frill striding ahead, Grobbard looking off into the vault of Fullbelly, and Squell, doublebodied, holding hands with all three of Fift’s bodies.

{Father Miskisk!} Fift sent. {I’ll do my best, Father Miskisk!}

All it was was sitting still and waiting to be passed a spoon, and saying “the spoon is in my hand,” and passing it on at the right moment. Saying the names of the twelve cycles, the twenty modes, and the eight corpuses of the Long Conversation. Sitting still in white shifts on a wood floor, zir heads shaved and oiled. Zir Vail parents waiting in the gallery outside. Ze’d do it well, and everyone would be proud, and there would be umbcake and sweetlace afterwards. And Father Miskisk would smile.

2

“So you’re latterborn again,” Umlish said. Ze smirked. “I guess we should congratulate you.”

Umlish was talki

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...