Morrigan was born small, about the size (though not the shape) of a donut. And she was quiet as the dawn; quiet enough to worry the delivery room, had it not been for her sly and beatific grin.

She grew slowly. She was the size of an extra-large cinnamon raisin bagel at eight months old, when the Mandatory National Baby Swap and Jamboree took place, and her original parents had to give her up in exchange for a plumper, longer, louder baby named Michael.

Given the national trauma and unresolved grief that festooned the Swap like garish, festive bunting—and given the garish, festive bunting that littered the nation like trauma and unresolved grief, in discarded drifts and dilapidated piles, in the days after the Swap—it is, perhaps, not terribly surprising that Morrigan was soon misplaced by her new family, the family which had swapped Michael for her.

They looked under the sofa; in the broom and coat closets; behind the Regulation-Conformant Cybernetic Gramophone and Family Fun Center; and in the pile of old sweaters on the rocking chair.

They sought Morrigan, but in their hearts, of course, they were wishing for Michael.

Those days were a confusing tumult. The air above the whole nation was choked with tears and muffled sobs. No one could quite forget the terror in the eyes of the Democratically Elected President and Social Harmony Vouchsafe on Channel One. It was a hard time to look for a baby, especially one you could not yet feel was your own.

Given the political ramifications of their carelessness, Morrigan’s new family could ask no one for help, and trust no one with their secret. The greatest risk of exposure was their older child, Luanda, a kind and bubbly four-year-old with a tendency (innocent enough in some moments of political history, deadly in others) to be chatty. So great was this risk that, having despaired of finding the baby, they fitted Luanda with a crude black-market memory squidge: a speck of cyberactive bio-sludge purchased in a parking lot behind the Appropriate Fashion Responsible Free Enterprise Distribution Palace. They smuggled it home in a bag of half-off control-top pantyhose; configured it, following instructions printed on crumpled newsprint, on an antique box-computer; and concealed it in the barrette with which Luanda always imposed order on her bangs.

This bit of sludge constantly informed Luanda’s brain that she had just seen the baby, and that the baby was doing fine, enabling her to answer nosy neighbors and Vibrant Community Ratings Coordinators with perfectly honest, if confabulatory, nonchalance.

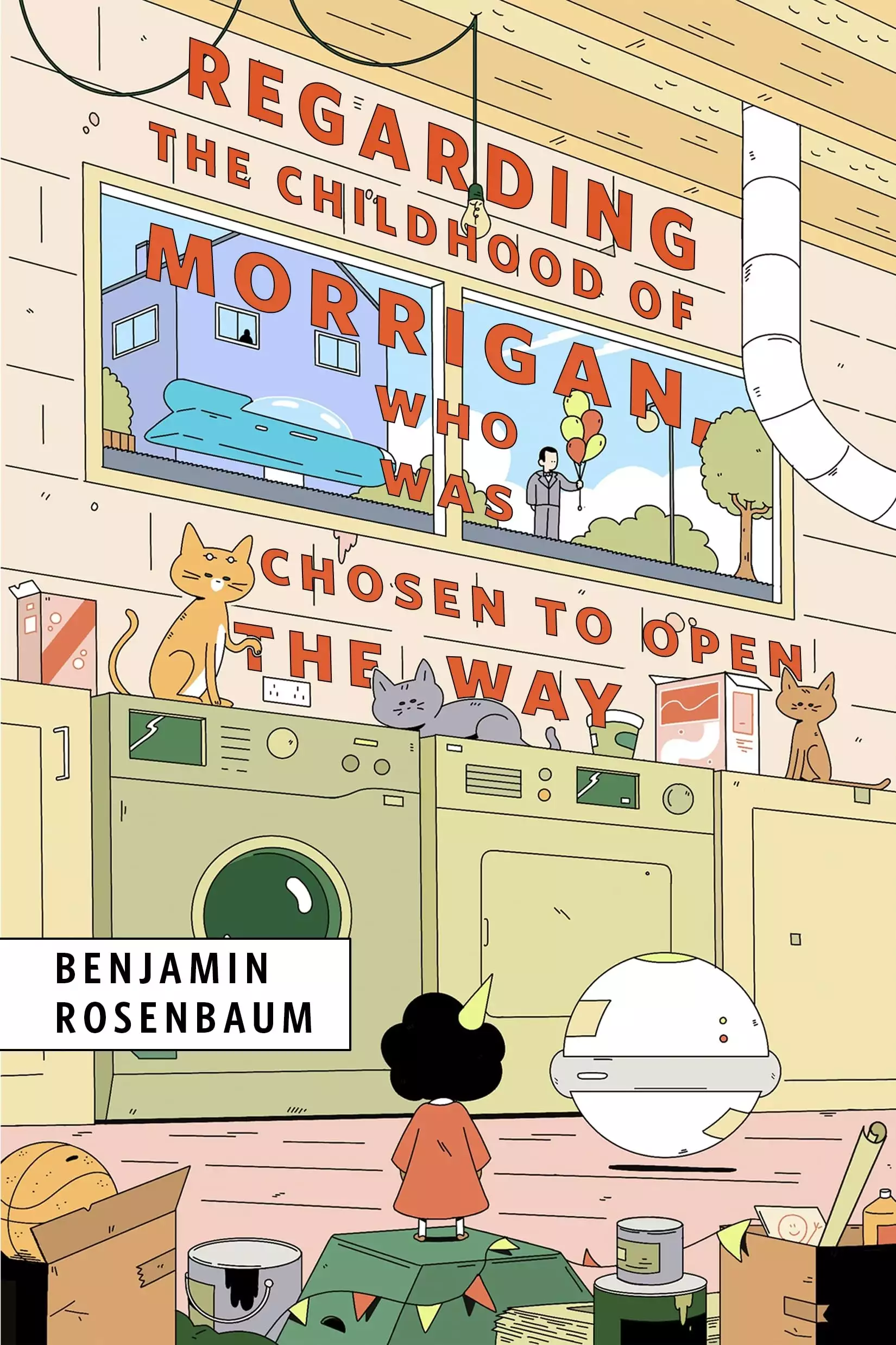

Morrigan herself, quiet as she was, quiet as a library at 9 a.m. on a Wednesday, had slipped between an unused extra washer and dryer in the unfinished half of the basement. How she got there is a bit of a puzzle. But she could already crawl a little; large loads of tantalizingly soft laundry were often carried down the stairs to the new model washer and dryer in the other half of the basement; and she was, after all, very small.

Morrigan survived due to an unusual combination of circumstances: a generous, copiously lactating new mother of a house cat; an adaptive cleaning robot which implemented situational-response protocols by downloading diaper-changing and bathtime modules; and her sister, Luanda. When Luanda would report back on what toys Morrigan liked, or how cute she was, or how it was

Morrigan who had eaten the rest of the oatmeal, her parents would be stricken with guilt and terror: one child misplaced, the other warped into delusion by back-alley bio-sludge.

Listless with self-blame, they stopped doing laundry, leaving the basement to its own devices. They expected a knock on the door any moment. Morrigan would be found somewhere, dead or alive. Luanda would be taken away. And they, themselves, would spend their last lucid moments dreaming of Michael, at the Families-First Helpful Behavior Restorative Justice Sharing Circle.

As the weeks dragged on and no knock came, they concluded that Morrigan’s original parents had somehow managed to steal her back. But this was a temporary respite. They would all be found out. It only meant that Michael, too, would be orphaned.

The knock would, indeed, have come, had it not been for the diapering performed by that capable cleaning robot. Kilograms of food into the house, kilograms of diaper sewage out; the numbers satisfied the pattern-matching algorithms, and finer-tuned, more contemplative monitoring had been removed in the last Commitment to Elegance and Function Gentle Refactoring and Purification Drive.

The year Morrigan was born, and then misplaced, there were found to have been an unacceptable number of data points of Resistance to Social Optimization. In response, there was a Responsiveness Clarification Spectacle. For weeks, it was all Channel One would broadcast. The fixed glitter-daubed smiles of the high-kicking Chorus Persons. The razzmatazz of the big bands playing Optimized John Philip Sousa. The soulful oceanic swell of the All-Celibate Aspirational Youth Responsibility Choir. And over it all, the begging, the screaming, the strangled sobs of the Democratically Elected President and Social Harmony Vouchsafe. It saturated the living room where Morrigan’s adoptive parents slumped on the pastel purple sofa, in their smelly, unlaundered clothes. Luanda played with her Creativity Encouraging Interlocking Construction Blocks.

Many people said, that year, that it took the President and Vouchsafe an inordinately, really an inconsiderately, long time to die, and that this really bummed out everybody. Certainly Morrigan’s parents were utterly bummed out.

would be unfair. They had one child left, Luanda. They loved her, and they knew their duty. But they also knew they had a bummed-out vibe. And a bummed-out vibe could be a lethal thing in that particular moment of political history. What if it negatively impacted their work assessments?

They began to up their dosage, and soon they were way past recommended daily, with predictable results: their work performance was restored, but their off-duty brains were riddled with aphasias, gaps, and dysmnesias, and the doubled, muddled trauma of the loss of Michael-Morrigan had become the organizing principle of their compromised psyches. By the time Morrigan—three years old and the size of a mushroom quiche—toddled up the stairs from the basement, that trauma was the only duct tape lashing the whole ramshackle affair of their consciousness together.

And so when Morrigan, dressed in a blue felt overcoat and a yellow hat (an outfit that Luanda had borrowed from her stuffed bear), trundled into the living room, her parents’ mental immune systems, in a spasm of self-preservation, rejected the whole idea. Their eyes saw her; the information traveled along their optic nerves; their basal optic processing regions resolved Morrigan into a cluster of colors and edges; but the higher perceptual regions, presented with the data, very politely declined, as a slightly inebriated minor Edwardian duchess might decline the last wilting watercress sandwich of a particularly unforgiving July brunch. The higher perceptual regions thanked the basal optic processing ones, but explained that they couldn’t possibly, it was all a bit too much, and they would much prefer to see a rubber plant, or a stray toy, or even a neighbor child wandered in from the street.

And thus they kept on mourning the loss of the very child who sprawled before them on the salmon-colored shag rug, gazing at them with curiosity, chewing on an Interlocking Construction Block.

And so Morrigan grew up with a sister physically incapable of doubting the fact of her presence, and parents psychologically incapable of recognizing it.

No political dispensation lasts forever, and this was no less true in that era—the era into which Morrigan was born, and which Morrigan would have a hand in bringing to a close—an era which described itself as The Grateful Recognition of Harmonious Inevitability, or as the Full Optimization of Human Potential, or as The Way Things Were Absolutely Unquestionably Always Intended to Be.

Morrigan was in the third grade, and Luanda in the seventh, at the local Proactive Interpersonal Growth and Unfettered Knowledge Discovery Supervised Collaborative Experience Oasis, when a war broke out.

The fact that Morrigan was managing a satisfactory performance and attendance record of mandatory Growth and Discovery Experiences—despite having adoptive parents who believed her to be their older child’s engineered hallucination—had required no little further adaptation on the part of their adaptive cleaning robot.

It had entered into a series of complex gambling rackets and Ponzi schemes, bamboozling the local crowd of weed-whacking, gutter-cleaning, calorie-intake-optimizing, traffic-monitoring, and Pedestrian Flow Enforcement robots, and raking in the dough. In this way, it managed to fund a series of new protocols, hardware upgrades, and expansions to its capabilities; with these, it was able to coordinate outfits, sign report cards, deepfake remote parent-teacher conferences, and help Morrigan use blunt-tipped scissors to cut out colorful paper neurons and ganglia and paste them into her Diorama of Human Pain Perception.

With its expanded capabilities—in addition to shepherding Morrigan through third grade—the adaptive cleaning robot watched the war happen. Indeed, it understood the war’s progress far better than most of its neighbors, including its supposed owners, did.

This was not a war of the old-fashioned kind. It did, of course, have some of the classic inherited features of wars of the past, such as pointy sticks plunged into human torsos, and explosions turning humans into mushy

Jackson-Pollock-style wall decor, and cybernetic intrusions shutting down power plants and causing planes full of screaming humans to plunge into the sea, and the exchange of modestly sized nuclear weapons, causing many humans to be vaporized instantly, to succumb to burns and radiation poisoning, or to reckon tearfully with greatly reduced lifespans.

But, of course, this war went far beyond that kind of simplistic and crude dominance display. This was not a war where you expected the enemy to just admit defeat out of rational calculation, or out of terror, sorrow, and exhaustion. This was the kind of war where you expected the enemy to wake up in a hall of mirrors, realizing that it was you yourself all along, and for the enemy to then reverse engineer its own inevitable demise with the fatalistic eagerness of a man unhurriedly finishing a hot dog that he knows has already delivered a lethal amount of plutonium to his system, but which is also, after all, a very delicious hot dog.

One feature of this advanced, contemporary kind of war was that, since the explication and propaganda systems were themselves a furious battleground, it was quite difficult for Morrigan’s parents to make out who exactly the combatant sides were. One day, Channel One would be encouraging citizens to whisper, in support of the Consortium for Eternal Harmony and Quiet in its battle to root out the Malevolent Noisy Dissidents. The next day, they would be informed that legions of the Necromantic Dead were hungry for their flesh, and to please support the Last Survivors of Earth by killing anyone who was not wearing a hastily fashioned Pointy Blue Indicator Hat. (The adaptive robot’s store of blue construction paper and blunt-tipped scissors came in handy here, and it and Luanda stayed up late making hats for everyone, including the cats.) The following week, Channel One insisted (to a background of falling bombs) that there was in fact no war, that the enemy was a Lack of Mellowness, that the falling bombs were a Mellowness Assessment, and that civilization could be saved by citizens demonstrating a Resolutely Undaunted Commitment to Maximum Chilling Out.

The chaos affected Morrigan’s adoptive parents’ work environment as well; every day they would be set to disassembling the things they

had assembled the day before, or to issue reports denouncing in advance the reports they would issue tomorrow.

Luanda valiantly tried to put her foot down about any further increased parental dosage of Productivity Vitamins. “It’s killing you!” she shouted. “It’s making you so weird!”

“Darling,” her father said, “please keep your voice down. What if the monitors hear? They’ll think we’re on the side of the Noisy Dissidents!”

“Oh my god, Dad,” Luanda said, “that was last week! Hello?? Now we’re supposed to show vigorous pride in our natural human bodies and denounce the Culture of Shame. I can’t believe you thought we were still supposed to be Eternal Harmony, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved