- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

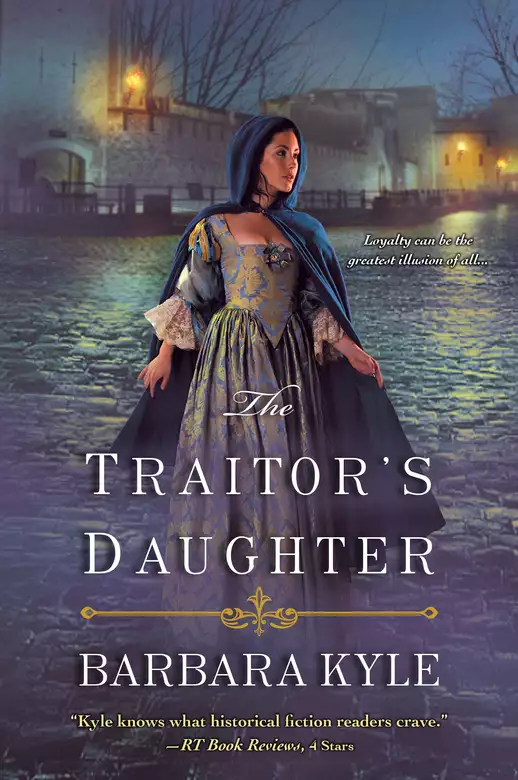

Synopsis

In 1582, England is gripped by the fear of traitors. Kate Lyon, tainted by her exiled mother's past treason, has been disowned by her father, Baron Thornleigh. But in truth, Kate and her husband Owen are only posing as Catholic sympathizers to gain information for Queen Elizabeth's spymaster. Kate is an expert decoder. The deception pains her, but she takes heart in the return to England of her long estranged brother Robert. If only she could be sure where his loyalties lie...

Kate and Owen’s spying yields valuable intelligence: English Catholics abroad are spearheading an invasion that would see Elizabeth deposed—or worse—in favor of Mary, Queen of Scots. Kate takes on the dangerous role of double agent, decoding and delivering letters the exiles send Mary. But when lives and fortunes hang by the thinnest threads, betrayal is only a whisper away...

A brilliant blend of Tudor history and lush storytelling, The Traitor's Daughter is a riveting, passionate novel of loyalty, heartbreak, and one woman's undaunted courage.

Release date: May 26, 2015

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 318

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Traitor's Daughter

Barbara Kyle

Thornleigh House was dark as Kate Lyon closed the door of her bedchamber, careful to be quiet. Cloak in hand, she went quickly down the stairs. Dawn pearled the lancet window halfway down, the sky luminously gray, as gray as the River Thames that flowed past the mansion. Kate glanced out, frustrated that the orchard trees obscured her view of the riverside landing. She could only hope the wherryman was there waiting. She had ordered the wherry last night. At the bottom of the stairs she turned into the great hall as the bell of the nearby Savoy Chapel clanged the hour. Six o’clock. Two hours to go, Kate thought. Her journey east to London Bridge would be just two miles, but the flood tide at this hour would slow her so she had to leave plenty of time. Her destination was the Marshalsea prison. Her husband had been a prisoner there for six months. At eight this morning he would be released. Kate was determined to be there.

She whirled her cloak around her shoulders as she crossed the shadowed great hall. The deserted musicians’ gallery that overlooked the hall was a black void. Even the tapestries Kate moved past were indistinct, the light too feeble yet to fire their gorgeous silk colors or to illuminate the gold-lettered spines of the books stacked on the dining table. The books were a new shipment from Paris that her grandmother had ordered. Old volumes—they smelled like dust. Having lived in Thornleigh House for six months Kate had become used to its two distinctive smells: old books and fresh roses, her grandmother’s twin passions.

She rapped her knuckles lightly three times on the table as she passed, a small ritual developed in her visits here as a child. Always three taps. For luck? She was twenty-two now and did not believe in luck, but some childish habits never die. The Puritans would call it a pagan impulse close to blasphemy. But then Puritans could sniff blasphemy in a summer breeze.

“So you’re going?” Her grandmother’s voice startled her.

Lady Thornleigh stepped out from the shadows behind the stacked books. Though seventy-two the dowager baroness stood as straight as a sapling. The velvet robe of forest-green she had put on over her nightdress was tied at her narrow waist, and her silver hair, plaited for sleep, curved over her shoulder. Even in the dim light Kate felt her grandmother’s dark eyes bore into her own. Kate had hoped to avoid this confrontation. Hoped their truce would hold. Straining for neutrality, she said, “You are up early, my lady.”

“You don’t have to do this.” Her grandmother’s voice was stern. A warning.

“Pardon me, but I do.” Nothing would stop Kate from meeting Owen when he walked through the prison gates. Her grandmother, though, stood resolutely in her way. “Please let me pass.”

“Do you know what you’re doing? Don’t you understand what your future will be? He will make you an outcast. From society. From our family.”

“If I am cast out it is not his doing. Nor my wish.” Owen had been arrested in a brewer’s cellar for attending a secret Catholic mass—an unlawful act. In disgrace by association, Kate had been snubbed by friends she had known for years.

“But it will be your lot,” her grandmother shot back. “Unless you stop.”

“I pledged my future at the altar. How can I stop?”

“By removing yourself from his bed and board. By showing that you will have nothing more to do with him. You have been a bride for scarcely seven months, you did not know his true character when you took your marriage vow. Separate yourself from him now, Kate, and all the world will approve.”

“All England, you mean.” Protestant England. Everywhere else in Europe Catholicism reigned.

“It is the land you live in, child. Its laws must be obeyed.”

If only you knew! Kate bit back the words. Secrecy was the life she had chosen now. Bed and board, she thought. Of the second, her husband had none. The crippling fine handed down with his imprisonment had forced them to sell his modest house on Monkwell Street by London Wall. Owen was homeless. Kate would have been, too, but for the charity of Lady Thornleigh. Kate’s father, Baron Adam Thornleigh, had made it clear she was not welcome at his house.

She lifted her head high. There was no turning back. “I am no child, my lady. I married the man my husband is, and I love the man he is. My life is with him. Nothing you say, or all the world can say, will change my mind.”

Lady Thornleigh’s eyes narrowed in a challenge. “And you expect to come back here? With him? Expect me to keep a felon under my roof?”

“If you will let us bide until we can find lodging, yes. If not, we’ll shift for ourselves.”

“You’ll shift . . . What impudence!” Her tone conveyed indignation, but Kate now saw something quite different creep over her grandmother’s face: the ghost of a smile. “Ah, my dear,” the lady went on, “you sound like my young self.” She stepped close and enfolded Kate in her arms. “This house will always be open to you, and to your husband. I must say, I admire you.”

Kate pulled back, astonished. “Admire?”

“I had to be sure you have the courage.” Tenderly, she caressed Kate’s cheek, a sad look in her eyes. “You are going to need it.”

The mansion was Lady Thornleigh’s town house, a home away from her country estate. Its cobbled courtyard faced the Strand while its rose-trellised rear garden and orchard sloped down to meet the Thames. Moving through the garden, Kate gathered her cloak about her, feeling the river’s chill dampness on the breeze. At the water stairs she found the wherryman napping in his boat, arms folded. Impatient, she rapped on the stern.

He snuffled awake. Lumbering to his feet, he made an awkward bow in deference. “My lady.”

She did not correct him. The grand surroundings and her fine clothes prompted him to call her that, but she was a lady no longer. Mere months ago she had been known as the daughter of a baron. Now she was the wife of a commoner, a felon. A Catholic.

“To Cock Alley Stairs,” she directed him. About to step aboard, she took a last glance at the house. Bless you, Grandmother, she thought with a grateful smile. A candle flared to life in an upstairs window. A maid coming down to light the kitchen fires, no doubt. The workday was beginning.

“Mistress Lyon?” a high voice asked behind her.

Kate turned. “Yes? Who’s there?”

A boy stepped forward. He looked about ten, dirty clothes, hair like a bird’s nest. The faint dawn light made a white pallor of his face. He looked unsure, as though cowed by the grandeur of the place, but Kate detected a native boldness in his eyes.

The wherryman cleared his throat. “Sorry for the fright, my lady. The lad was sitting here when I come. Said he was waiting for daylight to go up to you at the house. I told him you was coming down.”

The boy held out a sealed letter. “For you, m’lady.” The letter was as dirt-smudged as its bearer. Kate hesitated. She was used to receiving covert messages, but from couriers she knew and trusted. Surely her instructions would not come by way of this young stranger? “From my master,” the boy added.

She took the letter. “And who might that be?”

“Master Prowse.”

She could think of no such person. “A master of chimney sweeps, is he?” she asked with a wry smile. Soot blackened the boy’s hands.

He looked puzzled by her jest. “No, m’lady. Master of boys. Schoolmaster.”

A memory flickered to life. “Bless my soul, not Master Tobias Prowse? Stooped old man with a wart this side of his nose?”

“Aye, m’lady. The same.”

Prowse, the tutor who had taught her and her brother when they were children. It had been years since she’d seen the old man—a lifetime, it felt, given all that had shaken Kate’s world since then, but in fact it was just thirteen years ago that she and Robert had sat in their father’s study reciting Latin rhymes to Master Prowse. She’d been nine, Robert seven. Even at that age her brother had been more clever with the Latin than she was. A pang of regret squeezed her heart. She hadn’t seen Robert in a decade. They had been so close when they were children, inseparable, especially in that frightening time after their traitorous mother had fled with them to Antwerp. Three years later their father had got Kate back, but could not get Robert, and since then their secretive mother had again moved on with the boy, their whereabouts now unknown. It weighted Kate with guilt that she had been the one who got out, leaving Robert to endure a hard exile with their embittered mother. She could never shake the feeling that she should have done more to try to save him.

She looked at the sealed letter. A good old soul, Master Prowse. Old in those long gone days, so he must be ancient now. But why would he be writing to her? Perhaps about Lady Thornleigh’s book collection? Her grandmother had been quite public in seeking donated volumes for her ever-expanding library, which she intended to gift to Oxford University. Did old Prowse, feeling his end draw nigh, want to bequeath his humble collection to her? But that was fanciful thinking. More likely the poor man had fallen on hard times and was hoping for charity from Her Ladyship and felt Kate would be his link to her. Well, no doubt his letter would make all clear. She tucked it away in the pocket of her cloak. A petitioner, however deserving, could wait. Owen could not.

The candle in the upstairs window went out. No longer needed, for the pewter light of dawn was gathering strength. Kate dug into the purse at her waist for a coin for the boy. “Where have you come from?” she asked.

“Seaford, m’lady.”

The Sussex coast. “That’s a long way.” She gave him a shilling. His eyes went huge at the overpayment. “How did you come? A farmer’s cart?”

“Walked, m’lady.”

Over sixty miles, and shod in rough clogs. He was no doubt hungry, too. “Knock at the kitchen door and ask them to give you breakfast. Tell them I said so.” He brightened even more at that. She asked if he had a place to lay his head tonight.

He shrugged. “I can shift for m’self.”

She had to smile at this echo of her own defiant pride. “I warrant you can.” She told him he could sleep in the dovecote in the corner of the garden wall. “But stay clear of the steward,” she warned. The man was a Puritan and known to whip vagrants.

The moment Kate was seated in the cushioned stern the wherryman pushed off. With the current against them, and the river breeze, too, he strained at his oars, and the bow bucked against the choppy waves. Kate’s heartbeat quickened at the thought of seeing Owen, but beneath her excitement ran a ripple of uneasiness about the note she had received last night. Summoned to a meeting, both she and Owen. What could be so urgent that they would be sent for on the very day of his release? Kate doubted it was good news. Looking ahead at the waking city she felt a kinship with the struggling half light all around her, the night not quite yet vanquished by the sun.

Her spirits rallied in the bracing river air, and when the first beams of sun lit up London Bridge in the distance ahead her excitement rose, too. To have Owen with her again, a free man! Watching the buildings glide past she felt the great city cast its spell over her. The stately procession of riverside mansions stretched in both directions from the Savoy, their windows glinting in the rising sun. Ahead of her rose Somerset House, Arundel House, Leicester House; behind her Russell House, Durham House, York House, and the river’s curve that led to the Queen’s palace of Whitehall.

Across the Strand the leafy market of Covent Garden would already be bustling with people from nearby villages bringing their produce to sell. The mid-September bounty would be fragrant with fennel and fresh cresses, blackberries, quinces, and tangy damson plums. Watercraft of all shapes and sizes were busy on the river, some under sail, others under oars, some beating against the current, others gliding with it. At Paul’s Wharf the first customers were calling, “Westward, ho!” beckoning wherrymen to carry them upriver—lawyers and clerks heading for Westminster, most likely. More wherries rocked alongside the Steelyard water stairs, ready to take shipping agents downriver to the Custom House quay. Kate’s wherry passed a canopied tilt boat ferrying a pair of snoring, rumpled gentlemen, no doubt returning from an all-night carouse in Southwark. Fishing smacks trolled near a feeding bevy of swans. Through the still-distant arches of London Bridge Kate glimpsed lighters beetling from shore to unload cargo from ships moored in the Pool.

A peal of church bells rang the hour. Seven o’clock. She cocked an ear for the pattern: 1-3-2-5-4-6. When bell ringers rang a set of bells in a series of mathematical patterns they called it “change ringing,” and the patterns had pleased Kate for as long as she could remember. Her tutors used to sigh at her slowness with languages—Latin and Italian had been a struggle for her—but with numbers she was always at ease. The clear, calm beauty of mathematics spoke to her as no human tongue ever did.

Passing Queenhithe wharf she smelled the yeasty aroma of baking bread. Also, a whiff of the stinking tannery effluent polluting the Fleet Ditch. Above it all drifted the smells of charcoal, sawdust, and fish. She imagined the city coming to life. Yawning apprentices opening shops along Cheapside, milkmaids ambling down Holborn Hill, servants hefting water pots from the big conduit in Fleet Street, fishwives setting up stalls at Billingsgate. Lawyers would be hustling through Temple Bar and merchants striding into the great gothic nave of St. Paul’s to do business with colleagues. On the shore by the Three Cranes Stairs a couple of mudlarks, a boy and an older girl, were bent sorting their finds from the river’s sludge, intent on their task before the tide rose farther. Kate could never behold the city without a rush of affection.

Its brash, brawling exuberance had always enthralled her, even as a child. She had been born the year after Queen Elizabeth’s coronation and had spent her childhood here in the springtime of Elizabeth’s reign. At nine Kate had been torn from England by her mother and her exile had lasted four years. Now, she loved her homeland fiercely, as only an exile can.

She caught the sweet scent of apples drifting from an orchard. Autumn was nearing, and the shortening of days. The harvest would soon be over. In manors throughout England bailiffs would be making out the accounts for the year. Here in London the law courts would mark the beginning of the Michaelmas term.

London Bridge loomed ahead, near enough now that its four-story shops and houses, crammed close together, blocked the sun. Kate looked up at windows where the last candles and lanterns were going out. A flock of sheep on the Southwark side bawled as the farmer waited for the drawbridge to be lifted. The gatehouses on either end of the bridge were closed every night. This was the city’s only viaduct, so city-bound travelers who did not make it across in time had to spend the night in one of Southwark’s unsavory inns. Southwark was Kate’s destination.

The bawling of the sheep was drowned out by the din of water rushing between the bridge’s twenty stone arches. There, each tide created a dangerous rapids. When watermen on the roiling water jetted between arches they called it “shooting the bridge.” Kate remembered the thrill of it one brisk spring day when she was a child. Her father, a ship owner and an expert sailor all his life, had taken her and Robert in a boat from Paul’s Stairs out to his ship moored off the customs house, and on their way they shot the bridge. Rollicking through the tunnelled arch like a cork in a whirlpool, Kate had squealed in delight, her father holding her hand and grinning, but little Robert sat gripping the gunwale, big-eyed, rigid with fear. He did look rather comical, and Kate and her father had shared a laugh. That carefree time seemed so long ago—before her father became Baron Thornleigh, and long before Kate could ever have imagined the chasm that separated them now. The chasm that had opened with her husband’s arrest.

A ghastly sight jerked her out of her thoughts: the heads impaled on the bridge’s gatepost. Traitors’ heads.

Anger streaked through her, a sad fury that this normal bustle of daily life and commerce around her masked the deep anxiety of Londoners, of all the English people. A struggle for England’s soul held the country in a death grip. It was a struggle that had turned friend against friend, parent against child, twisting her countrymen’s honest passions into hatred and fear. The first blast had come from Rome with the pope’s declaration that it would be no sin for any Catholic to kill Queen Elizabeth. Since then Her Majesty’s government had kept up a relentless search for radicals. Assassination plots had been thwarted. Missionary priests preaching allegiance to the pope above the Queen had been captured and hanged. The government’s position was rigid, implacable. To be a Catholic in England was to be a traitor.

Kate felt equally implacable as she gazed up at the grisly, withered heads. The blithe springtime of Elizabeth’s reign was over.

Shifting her position on the seat, she heard the rustle of the paper in her cloak pocket. The letter from old Master Prowse. A voice from those happy long-gone days would cheer her, she thought. She pulled it out and opened it. It read:

So, he did not know she was married. He must have sent the letter to her father’s house and there the boy had been redirected to Lady Thornleigh’s. She read on:

Kate looked up with a gasp. Robert—back in England! A physician! She read on hungrily:

“Cock Alley Stairs, my lady,” the wherryman announced.

Kate looked up. They were approaching the wave-splashed steps on the Southwark shore.

Southwark was the squalid side of the Thames, known for its unsavory haunts. The Marshalsea prison was minutes south of the river. Making her way along Bankside, Kate could not stop thinking of Robert. What joyful news! She longed to see him. Would she even recognize him? He’d been a child when they’d been separated and he was now a man of twenty! Curiosity burned in her to know about their mother, too. Where had the two of them lived all these years? How had they lived? She thanked God that Robert had broken away, had come home, and she was eager to assure him that he could rely on her for whatever help she could give. And yet, what help was that? She had no influence with their father. And a reunion with her might even worsen Robert’s position. Should she simply let him be? Leave him “in peace” as he’d asked Master Prowse, to make his way alone? That felt heartless—and not at all what she wanted. But which course was better for him?

At St. Saviour’s church she turned south onto the main street. It was strewn with refuse. She sidestepped a scummy heap of cabbage leaves and bones. A skinny dog trotted past her toward the bones. Alehouses, dilapidated inns, and brothels lined both sides. Stewhouses, Londoners called the brothels. The Bishop of Winchester, whose riverside palace was the grandest structure in Southwark, was responsible for maintaining law and order in the area, and because he licensed the prostitutes they were known as Winchester Geese. Kate glanced up at a weathered balcony where a woman in flimsy dress was brushing her hair with tired strokes, her eyes closed to enjoy the sun’s warmth on her face. A weary goose, Kate thought with a twinge of sympathy as she walked on. A kite flapping its wings above the Tabard Inn descended into an elm tree and alighted on its nest of scavenged shreds of rags. A beast bellowed from the far eastern end of the street. The bear pits and bull pits there regularly drew afternoon crowds.

Kate knew the area. As children she and Robert had come with their father to the yearly Southwark Fair. Again, Robert and memories of those carefree days filled her thoughts. The fair had been such fun, a boisterous event attended by large crowds, both lowborn and high, who came to marvel at the tightrope acrobats and dancing monkeys, to eat and drink too much and, if they were not careful, to have their pockets picked. Now, a bulbous-nosed man lounging in a doorway leered at Kate as she passed. She picked up her pace. Thieves abounded here. Many ended up in one of Southwark’s prisons: the Clink, King’s Bench, the Borough Compter, the Marshalsea. Conditions in all were appalling, even for the wealthy who paid to live in the Masters section separated from those in the Commons, but Kate feared that the Marshalsea was the worst. Its inmates were entirely at the mercy of the Knight Marshal’s deputy. While the master’s side had forty to fifty private rooms for rent, Owen had had to endure the common side, nine small rooms into which over three hundred people were locked up from dusk until dawn. It made her shudder.

“Penny for the poor prisoners, my lady?” An earnestly smiling man in shabby clerical black held out his hand for an offering. All prisoners had to pay for their own food, so without charity the poorest often starved. Churchmen begged coins to buy them bread. This fellow, though, looked to Kate more pirate than prelate. The donations he weaseled would likely go to buy himself grog. She ignored him and carried on, but with a knot of dread tightening her stomach. She had paid the marshal’s deputy every month to supply her husband with food, but had that food reached him?

She turned the corner at the Queen’s Head Inn and the Marshalsea rose before her. Two long mismatched buildings, the gray stone walls slimed with black, the brick ones crumbling in places after more than a century of neglect. The arched double gates of wood were closed, and a small crowd of twenty or so men and women stood waiting for them to open. Kate had made it—the bell of St. Saviour’s had not yet chimed eight. Though the gates were a solid barrier, a stench seeped out like swamp fog. A scabby-faced girl hawked rabbit pasties, to no takers. An elderly churchman, this one looking genuine, begged coins to buy food for destitute inmates. A solemn young man with a mustard-colored cap moved through the crowd offering willow crucifixes for a ha’penny. A couple of painted women lounged in the shadowed angle of the wall, awaiting trade. Kate looked up to an unglazed window above the gates. A wild-haired man glared out at the crowd from between iron bars. He spat. Kate looked away.

A clang behind the gates. A rattling and grating as one of the wooden doors was marched open from inside by a ragged worker. The people surged forward, most of them straight into the prison courtyard. Kate stood still, craning to see beyond the moving heads and backs. Then she saw him, Owen, a head taller than most of the other men. She gasped. How thin he was! And how dirty. And what had happened to his hair?

He saw her, and his deep-sunk eyes brightened. He strode to her, shouldering past the people streaming the opposite way. She ran to meet him.

They stopped, face-to-face, hers upturned to his, both of them gazing, the moment too charged for words. Kate was shocked by his hollow cheeks, hollowed eyes. His hair, once a rich black mass of lazy waves, was now so close-cropped it was as thin as a shadow on his skull, with erratic tufts, and nicks in the skin as though a drunken barber had wielded rusty shears. Black stubble bristled his chin, as ill-shaved as his head. His doublet of chestnut-colored wool was rumpled and grease-stained. A rip in his shirt’s collar was so straight it could only have been cut with a blade. He stank.

Tears sprang to her eyes. “What have they done to you?”

He gave her a tight, forced smile. “A fine day, wife. Thank you for coming.”

The words were oddly impassive. His voice strange. So was the look in his eyes, glassy yet intense.

No, she would not have this! She threw her arms around his neck and went up on her toes and pressed her cheek to his. He held himself rigid. Would he not embrace her? Shocked, she pulled her head back. “Owen, are you ill?”

His glassy look dissolved in a faint film of tears. He gathered her in his arms and pulled her close. He held her so tightly she could scarcely breathe. “No,” he murmured shakily. “Not ill.”

She felt a tremor run through his body. She suddenly realized: the formal greeting, the rigid stance—it was to clamp his emotions inside, to forbid himself any show of weakness after his ordeal. Kate’s tears spilled. From love, from pity. Then, quickly, before she could speak any more of her heart, she let him go. She must not undermine his effort. Must not unman him.

Swiping away her tears, she looked at his shorn scalp and forced a wry smile. “I cannot say I like this new fashion.” She ran her hand over his head and shivered at the stubble sharp as pins.

He matched her half smile. “Less of a handhold for lice.”

Warmth rushed through her at his jest. This was the Owen she knew and loved!

His eyes flicked to the young man selling the willow crucifixes a stone’s throw away, then back to Kate, a clear warning. He said very quietly, eyes still fixed on her, “A disciple of Campion.”

Edmund Campion, executed last year, the most famous of the priests secretly sent by the Jesuit order in Rome to preach defiance of the Queen. To Catholics, he was a martyr. To Protestants, a traitor. Kate understood what Owen was telling her. We’re being watched.

“You?” she asked quietly. He suspects you?

He shook his head. “You.”

She was not surprised. Because of Father. Yet still, it stung.

“Ah, wife,” he said, his voice suddenly loud and sorrowful, loud enough for the spy to hear, “a prison is a grave for burying men alive. It is a little world of woe.”

His theatrical words were deliberate, Kate knew—a poetic lament that might be expected from a playwright, for until a year ago that was how he had made his living, meager though it was. He could bewitch you with words. He had bewitched Kate from the moment she’d been introduced to him at the playhouse called the Theatre.

“And how are you, my love?” he asked. This time his simple sincerity rang through.

“Well. Very well.”

“And your lady grandmother?”

“A rock.” Her gratitude to her grandmother was heartfelt. The lady was an island of tolerance in a sea of mistrust. “You will be welcome in her house.”

“We’ll find our own house soon, I promise.”

She smiled at him for that.

The bells of St. Saviour’s chimed the hour. The young man selling crucifixes moved away. Kate watched him go. He was well beyond hearing them now, but still she lowered her voice to a mere whisper. “Owen, we are summoned.”

It startled him. “Now?”

“Now.”

He ran a grimy hand over his stubbled chin. “I need to wash. Shave.”

“You need to eat.” Fury at his mistreatment shot through her again. “They starved you!”

He shrugged. “No more than the others.”

If only he had let her give that wretched deputy more silver! For another few pounds he would have had meat and drink fit for the Masters. But she knew why he had refused. He’d needed to bear the misery, because it was essential that the Catholic inmates accept him as a fellow sufferer. What those inmates did not know, and must never know, was the real reason he had agreed to suffer. In this battle for England, Owen had pledged himself to protect Her Majesty. And so had Kate.

“Come,” she said, “I have a boat waiting.”

He took her elbow. The squeeze he gave it told her how much he would rather be alone with her than hurrying to a meeting. But he said steadily, “Lead on.”

Kate and Owen took the wherry. As they were rowed across the Thames they were so locked in looking at each other she. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...