- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

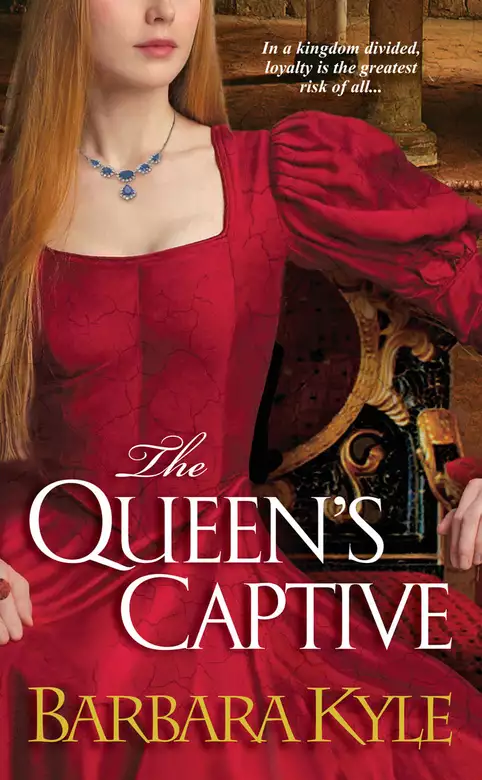

England, 1554. In the wake of the failed Wyatt Rebellion, a vengeful Queen Mary has ordered all conspirators captured and executed. Among the imprisoned is her own sister, twenty-one-year-old Princess Elizabeth. Though she protests her innocence, Elizabeth's brave stand only angers Mary more.

Elizabeth longs to gain her liberty--and her sister's crown. In Honor and Richard Thornleigh and their son, Adam, the young princess has loyal allies. Disgusted by Queen Mary's proclaimed intent to burn heretics, Honor visits Elizabeth in the Tower and they quickly become friends. And when Adam foils a would-be assassin, Elizabeth's gratitude swells into a powerful--and mutual--attraction. But while Honor is willing to risk her own safety for her future queen, aiding in a new rebellion against the wrathful Mary will soon lead her to an impossible choice. . .

Riveting, masterfully written, and rich in intricate details, The Queen's Captive brings one of history's most fascinating and treacherous periods to vibrant, passionate life.

Praise for the novels of Barbara Kyle

"Weaves a fast-paced plot through some of the most harrowing years of English history." --Judith Merkle Riley on The Queen's Lady

"Excellent, exciting, compellingly readable." --Ellen Jones on The Queen's Lady

"Unfurls a complex and fast-paced plot, mixing history with vibrant characters." --Publishers Weekly on The King's Daughter

Release date: May 26, 2011

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Queen's Captive

Barbara Kyle

Through the long, dark hours Elizabeth had stared from the window at the garden made darker by the rain, knowing that if they were coming they would march along the gravel path under the bare, forked fruit trees. For three weeks the Queen’s guards had kept her a prisoner in these remote corner rooms of Whitehall Palace. The patch of winter-dead garden had been all she had been able to see of the grounds. Music and laughter from distant banqueting rooms had reached her faintly, like echoes of the life she had lost.

Voices of the guardsmen at her door made her turn sharply from the window. Two lords of the Queen’s council marched in past the guards. She had been wrong, they had bypassed the garden. Henry Radcliffe, Earl of Sussex, shook rain off his cap with the air of a man irritated at being burdened with unpleasant business. William Paulet, the sixty-year-old Marquis of Winchester, seemed far more troubled by their mission. Stroking rain from his wiry gray beard, he looked at the floor, and Elizabeth knew the old gentleman well enough to realize he was avoiding her eyes. Both men, with their damp garments and grave faces, brought in a chill that reached her like a cold hand at her throat. She had to swallow hard before she found her voice.

“My sister’s reply?”

Sussex clapped his cap back on. Elizabeth felt a jolt of anger. He should be kneeling. They should both be kneeling.

“None, madam.”

“But, my letter—”

“Her Majesty did not read it.”

It knocked the breath from Elizabeth. One moment—that was all she had entreated of the Queen. One moment, face-to-face, to swear that she was innocent of any involvement in the rebellion. I pray God that evil persuasions persuade not one sister against the other, she had written. I humbly crave only one word of answer from yourself. But her begging had been for naught. Mary would show no mercy.

Elizabeth stood tall, rallying her courage. She was the daughter of a mighty father, great King Henry the Eighth. She would not let these lords see her terror.

They led her out into the cold March rain. She was twenty years old and on her way to die.

They took her down the Thames toward the Tower. She sat shivering in the barge under a dripping canopy, as pewter-cold waves heaved around her, and pewter-gray clouds poured down their frigid rain. Her fingers, gripping the seat edge, were purple with cold. The turbulent river, reeking now at low tide, churned up smells of dead fish and decaying sea matter, turning her stomach. Above the din of waves beating the hull and rain beating the canopy, church bells clanged throughout London. It was Palm Sunday, the beginning of Holy Week. Elizabeth’s pious sister had brought back all the old Catholic rites—there would be creeping to the cross on Good Friday—and she and her council had ordered all the people to go to church this morning. “Keep to the church, and carry your palms!” had been the criers’ calls through the muddy streets. An ideal diversion, Elizabeth thought bleakly, for the religious ceremonies would keep Londoners from seeing the barge carry her away. She gazed out at the seemingly deserted capital with its scattered steeples thrusting into the gray sky. All those people crammed into the churches. She thought, Their palm fronds will have wilted in this downpour. Their stick crosses will be soggy relics for Mary’s priests to bless. She imagined them hurrying to get in out of the rain in their wet clothes—rough, homespun wool on fishwives and apprentices, rich velvets and brocades on the great merchants and their wives, but all of them jostling together, sharing a sense of community that she was now cut off from.

She had been arrested at her country home at Ashridge, and when they had brought her into London she had seen the grisly evidence of her sister’s justice. Gallows heavy with decomposing rebel corpses stood at every one of the city’s gates and in all the market squares. Body parts of rebels who had been hanged, drawn, and quartered were strung up along the city walls, a nightmare vision of dismembered arms and legs, the stench making the street dogs howl.

London Bridge emerged ahead through the rain. Its three- and four-story houses and shops looked as deserted as the city streets. Its stone arches bristled with spikes stuck with the gaping heads of rebels. Elizabeth thought she could smell the decaying flesh, putrid on the waterlogged air.

The river, squeezed between the viaduct’s twenty huge arches, roiled in treacherous rapids, and the bargemen squared their feet wide, preparing to “shoot the bridge.” Elizabeth gripped the gunwale to steady herself. The barge rocked and pitched in the angry water as it tumbled through the cavern of the stone arch. The light darkened. The water beat a hollow roar that echoed off the stone. The barge shot out the other side, wallowing in the confused currents, jolting Elizabeth’s neck and knocking her knee against the hull.

Her heart thudded as she saw the Tower through the steely curtain of rain. It lay dead ahead on the northern shore. Ancient royal fortress, palace, and prison, its precincts were a labyrinth of stone walls and towers and turrets that rose, massive and forbidding, crushing Elizabeth’s nerve.

Again, she plumbed a wellspring of strength from somewhere deep inside her and summoned defiance. “Not in by Traitor’s Gate, my lords. I am Her Majesty’s true subject and no traitor.”

Winchester’s voice was sad and kind. “Take heart, madam, the tide is with you.” The low water made it impossible to enter by Traitor’s Gate, a water gate. Instead the bargemen were rowing for Tower Wharf. Small victory, Elizabeth thought.

Yet Winchester’s somber face, showing how little he relished his duty, suddenly gave her heart. She had friends. Many friends. Influential men. Lord Admiral Clinton. The Earl of Bedford. Sir Nicholas Throckmorton and Sir Peter Carew and Thomas Parry and John Harrington, and her favorite, the stolid Sir William Cecil. A mad hope swept her. They would rescue her! Yes, Sir William was hiding there in the windswept rain on the wharf, waiting with a troop of soldiers. They would attack her escort and spirit her away to safety!

But no friends came as the two lords marched her across the drawbridge and into the Tower’s western precincts. She splashed through puddles that left her feet and ankles icy. Her sodden cloak, heavy on her shoulders, chilled her to the bone. Loose strands of her red hair plastered her neck, dripping icy water on her skin. The lieutenant of the Tower, Sir John Brydges, met them and led her across the narrow causeway. His soldiers lined the route hemmed in by the high stone walls. Rain drummed their steel helmets. Brydges led the party past the royal menagerie where Elizabeth could hear a lion roar. She did not flinch. She would not show the soldiers her fear.

One of them dropped to his knee and tugged off his helmet as she passed. “God save Your Grace!” he said.

Her heart leapt at this. A few other soldiers pulled off their helmets, too. But the show of loyalty changed nothing for her grim escort, who marched her on. She looked up at the stone walls glinting black with rain. Men were being tortured beyond those walls, she knew, tortured to scream out what they knew of her complicity in Wyatt’s rebellion. Wyatt himself was a prisoner here. So was the mighty Duke of Suffolk. Mighty no more.

She passed under the inner tower they called the Bloody Tower and glimpsed, across the courtyard, the scaffold on Tower Green. Terror stabbed her. Just weeks ago her cousin Lady Jane Gray—queen for nine chaotic days—had stumbled up the steps of that scaffold. Trembling, she had groped in confusion for the block on which to lay her head, and the Queen’s executioner had brought his axe thundering down. Pitiful, bewildered Jane, just sixteen years old. Yet the rebels had not fought in her name, but Elizabeth’s. How much more cause, then, did Mary have to hate Elizabeth?

Her bravado suddenly deserted her, and with it all the strength in her legs. She sank down on a wet stone step, shivering, faint with fear, lost. Her fingers groped the grainy stone, her fingernails grating. The icy wetness seeped through to the skin of her thighs, to her very bones. Mary’s hate for her was a well so deep, Wyatt’s treason had merely topped it up. Its wellspring had been Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Boleyn, despised by Mary for supplanting her own mother, Catherine, as Henry’s queen. Mary’s years of suffering before coming to the throne all stemmed from Anne. Now, as Queen, she was going to make Anne’s daughter pay.

“Madam, you cannot tarry here,” Sussex urged.

“Better here than in a worse place!” Elizabeth cried. “For I know not where you are taking me.”

The place they took her, through Coldharbour Gate, was both better and worse. Better, for it was no dungeon or filthy cell but a fine room in the ancient royal palace in the inner ward, a room warmed by a brazier of coals and resplendent with a bed plump with satin cushions and fresh, embroidered linens. Worse, though, because this was the very place where her mother, condemned by the King, her husband, had been lodged before he had executed her. This was Mary’s cruelest blow! Walking in, Elizabeth smelled coal dust and iron filings, and imagined her mother’s terror when she had been brought here, knowing that she would walk out only to her death. Elizabeth had been two years old. Later, she had heard the tales of her mother’s reckless courage in those days. Knowing that the axe of an English executioner sometimes hacked two or three times to finish its grisly job, Anne had demanded that an expert French swordsman be imported to make one clean cut.

The guards shut the great iron bolts of the door behind Elizabeth. No one had come to rescue her. Later that very day she heard drums and commotion as they led out the Duke of Suffolk, and then the executioner’s axe thundered down again. She tried to muster her mother’s courage. She knew she would be the next to die.

The tavern’s low ceiling and rough lumber walls had trapped generations of Antwerp’s harbor-front smells—fish, stale beer, wet rope, and salt-encrusted clothes. Boiled turnips, too, Honor Thornleigh thought as she walked quickly through the room. Winter fodder. Staple of the poor. She ate turnips too often these days.

She passed seamen sitting over pots of ale, their desultory talk a stew of many languages—Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian. One man, dressed in the fine doublet of a ship’s master, looked up from his foamy tankard as Honor passed. She lowered her face to hide it behind the edges of her furred hood. She had chosen this sailors’ haunt far from her house, but Antwerp’s mercantile community was as tight as a gossiping village and she couldn’t risk being seen by one of her husband’s business associates. Richard had no idea what she was doing behind his back.

She went straight through and out the tavern’s back door, and across a cobbled courtyard that stank of gutted fish, where the gusting November wind chased dead, dry leaves. She was relieved to enter the stable with its friendlier smells of hay and horses.

George Mitford was already waiting. He stood at a stall door, scratching the nose of a shaggy bay mare who bowed her head in contentment.

“She seems to love that,” Honor said, throwing off her hood.

He smiled when he saw her. “We all love a good scratch.”

“Scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours?”

“And so the world goes round, my dear.”

She gave in to impulse and embraced him. “Thanks to old friends, yes.” She paid for her action with a sharp spasm at her rib, cracked by a bullet ten months ago.

“Now, now, don’t tease,” he said as he pulled back from her embrace. It was his jest, but said with a blush that Honor found endearing, the cheerful fluster of a man who had not forgotten the passionate impulse of youth. She was forty-four and he was ten years older, but he was still fit, still possessed of a thick head of hair, though it was sheened with silver. In the old days, back in England, his hair had been as dark as Honor’s was still. Was that really more than two decades ago? He had caught her by the waist under the stairs on Richard’s ship as they had sailed into this very harbor, delivering George to safety from the heretic-hunting persecution of the bishop of London, and in that moment he had fervently declared his love to her. She had laughed. George was not the first man she had rescued whose giddy gratitude had flashed into ardor. “And all I had to do,” she’d teased, “was save your life.”

Now here he was, saving hers.

She noticed the sturdy case at his feet, a strongbox covered with amber leather, secured with studded copper bands and an iron lock. He was never without it. She glanced over her shoulder to make sure she had not been followed. There was no one. Just the soft chomping of horses munching hay, and the keening of wind across the roof’s patched holes. She was satisfied that she and George were alone.

She opened her cloak to display the top of her bosom to him, and touched her necklace, an almond-sized emerald pendant on a chain of filigreed gold. The gem was warm against her fingertips, her body’s heat infusing Richard’s gift from the summer they were married twenty-one years ago. To her, it held the essence still of that sweet, English summer. She bent her head to undo the clasp, then handed over the necklace. “I couldn’t give it to anyone but you, George.”

She saw a moment of deep feeling in his eyes before he lowered his gaze to study the goods. His demeanor was suddenly all business. “Milky inclusion in the left quadrant. Old-fashioned cabochon setting. A nick in the clasp.”

Honor winced at the criticism. She loved this necklace, a golden filament with its drop of green fire that connected her to happier days. But she stilled her tongue. George knew how much she needed the cash. He had been buying her jewelry, piece by piece, for months. She glanced down at his leather case, aching with curiosity. Were any of her gems still nestled in the black velvet lining, or did they already adorn his pampered clients? Her ruby earrings that Isabel, as a baby at her breast, had reached out to grab. Her rope of pearls bought on a trip with Richard to Venice. The diamond and sapphire ring he had given her seven years ago after a spectacular wool season. Her brooch of opals and topaz, an heirloom from the mother she had never known—Honor had planned to give it to her stepson Adam’s intended at their official betrothal. Her bracelets and necklaces of garnets, carnelian, amber, and coral, of lesser value yet cherished all the same. She lifted her eyes from the case, fending off the tug of regret. Her family could not eat rubies and pearls.

As always, George gave her an excellent price. Far better, she knew, than the emerald was worth.

The wind tugged at her skirt as she made her way home along the river Schelde’s crowded quay. Tall ships’ masts loomed over her, their furled sails stacked in massive tiers that blocked the watery sun. Their taut ropes creaked, straining against the wharf’s bollard posts in an age-old sea song. Winter was bearing in from the frosty North Sea and seemed to make the sailors and tradesmen hustle more earnestly in and out of the chandleries and harbor offices and boat sheds. She passed men hefting sacks from the hold of a Portuguese carrack pungent with a cargo of pepper and cinnamon.

She looked to the broad river’s western horizon. Was Adam’s ship sailing into the estuary right now, she wondered, battered from its battles with Russian ice? Would he make it back for tonight’s feast for Isabel? He had written from the port of The Hague to say he intended to be there, and Honor hoped that the wind and tides would indeed bring him. It would be a sadder party without her seafaring stepson.

There were shouts from crewmen on board a magnificent galleon coming alongside the wharf, its bright banners fluttering, and she stopped to make way for a gang of wharf hands jogging forward to secure the ship’s hawsers. Venetian, by its flag, and alive with men on the decks readying lines, and boys in the rigging, furling canvas. This controlled chaos of river traffic always impressed Honor. Antwerp was the trading and financial center of Europe, thanks to its fine seaport and crucial wool market, and hundreds of ships passed through here every day, making it an international city, with sailors and merchants and financiers hailing from Spain, Portugal, Venice, France, England, Poland, Sweden, and beyond. Antwerp embraced them all with a tolerance that Honor admired. The sights and sounds of the hectic river commerce reminded her of the busy Thames, and London, and a wave of homesickness rushed over her. How she missed England! But she and Richard were exiles. He was wanted as a traitor. They could never go home.

But what future lay here? The view of the ships dragged her thoughts far out to sea, south to Cadiz, to the storm four months ago that had cost them so much. She saw Richard’s two caravels pitch in the storm’s black fury. She heard their hulls smash on the rocks, the wood shatter, heard the screams of men hurled overboard. She felt their terror as they drowned, thrashing in the black depths.

She turned abruptly away from the water. Pointless to torture herself with visions of the catastrophe. She left the harbor and headed for home, her purse heavy with George’s coins, her heart heavy with regret. And something sharper. For the first time she felt fear. All her jewels were now gone.

John Cheke, a Cambridge don, announced the toast. “To Isabel and Carlos!”

The twenty-three men and women crowding round the Thornleighs’ dinner table raised their glasses high. Bright candles warmed the snug town house near the heart of Antwerp’s Grote Market. Richard had bought it, a fashionable address, in the heyday of his wool-trading business, to be a second home for his frequent trips from England. Now, Honor hoped their neighbors didn’t suspect that they could barely maintain the upkeep. “To the young couple,” Cheke cried. “The enemies of New Spain will quake at Carlos’s sword!”

“And if that fails,” a bookbinder quipped, “he’ll unleash a real terror—his wife!”

Everyone laughed, the toasted couple loudest of all. Isabel flashed her imitation of a fierce warrior’s face at her Spanish soldier husband. It made him throw back his head and roar with laughter.

Even Honor had to laugh—though her daughter’s exploits still astonished her. She glanced at Richard down the table and saw him, too, gazing at Isabel in wonderment. Their daughter, just twenty, had proved herself to be not the innocent they thought they had raised, but an audacious rebel who, a year ago, had helped Wyatt’s uprising almost bring down England’s Queen Mary I. It had happened as Honor lay here, barely conscious, sunk in a fever from a gunshot wound, and when she had recovered enough for Richard to tell her the tale, she had found it incredible. Isabel’s choice of husband had surprised her almost as much—Carlos Valverde, a mercenary soldier, unschooled, accustomed to very rough ways. But when she heard how he had saved Richard and Isabel, she had embraced him like a son. The wedding three months ago had been a happy interlude in the family’s financial troubles.

Adam’s wedding would be next. That would be a grand affair, and the rich connection very promising for the family, Honor hoped. It saddened her that the tides had not brought her stepson tonight, after all, but she did not indulge fears of a mishap. If any man knew his way around a ship, it was Adam.

Her eyes met Richard’s. He was head and shoulders taller than many of the men here, and with his leather eye patch and sea-weathered face and storm gray hair, he put her in mind of a rugged rock rising above the shallows of other folk. Tonight, though, he looked careworn and all of his age, a craggy fifty-six. As her glance met his, their smiles at the toast gave way to a mutual sadness. This was a farewell party. Isabel and Carlos were leaving for the New World.

All day, organizing the modest feast, Honor had tried not to give in to her sense of bereavement. When would she ever see her daughter again? She watched Richard quickly drain his goblet of wine and then pour himself another. It worried her to see him drinking so much, drowning his own hard regrets. He had wanted to give Isabel and Carlos some of the land he owned in England, determined to keep his family together, but instead, to make a living, Isabel and Carlos were sailing half a world away. Honor knew how it was gnawing at Richard. Queen Mary’s officers, in confiscating the moveable goods of all known rebels, had snatched everything at their home in Colchester, from flocks to looms. His fulling ponds and mills sat idle, his tenting yards fell daily into further decay, his warehouses lay stripped bare. And the manor house he and Honor had built—her beloved Speedwell House, named after the wildflower so dear to her heart—was reduced to a hulk. She knew how Richard longed to go home and revive his international wool cloth business, but that could never be. If he set foot in England, he would hang.

“Honor, your tankard is empty. That will never do.”

She turned to the affable face of John Cheke, who filled her mug with ale, the twinkle in his eye belying his reputation as a distinguished Cambridge scholar. She shook off her melancholy and quaffed some ale, truly pleased to see these good friends who had come to bid Isabel and Carlos good-bye. All were exiles, many worse off than she and Richard were. With George’s coins she had sent her scullery boy to pay off her debts to the butcher, the fishmonger, the grocer, and the vintner, and with her credit good again—for a while, at least—she had set a hearty table of English fare for these fellow refugees from Queen Mary’s oppression. The roast beef and beer, eel pie and cider, baked apples and custard, were comforts to a homesick community. A queer little enclave they had created, she thought as she watched John Abel pass the hat. As usual, he was collecting for the Sustainers of the Refugees Fund. There were hundreds of exiles throughout the Low Countries, and for those here in Antwerp her house had become a meeting place, a home away from home for hard-up Protestant gentry and scholars. Erasmus, her late mentor, would have loved the constant chatter about books and the New Learning.

They liked to dance, too. Honor called on the trio of musicians to play, and Isabel and Carlos had just got up to start the first dance when the maid hurried in, wiping her hands on her apron, her eyes shining. “It’s Master Adam!”

Honor turned with a happy smile. Her stepson had made it, after all. Adam strode in with a burlap sack slung over his shoulder like Father Christmas, and looking as jovial, if not as old, his beard not long and white but trim and black. Isabel cried out with joy and rushed over to her brother and threw her arms around his neck, crying, “You came!” Carlos clapped a congratulatory hand on Adam’s shoulder, saying, “And in one piece.” Honor hugged him in delight and welcomed him home. Richard shook his son’s hand in heartfelt silence.

The guests hadn’t seen Adam since his return from Russia, and as everyone crowded round, welcoming him, Honor looked on with a swell of pride. She knew from his letter the story of the Merchant Adventurers’ voyage. They had endured terrible privation, he had written, losing ships and men, and were returning with little profit to show for it. Reading between the lines, though, Honor gathered that Adam had acquitted himself bravely, helping to lead the remnant of the expedition overland to Moscow. At the guests’ urging he was telling tales of the extraordinary court of Czar Ivan IV—of caviar and saunas, and harbors teeming with whales. She watched him gesture as he talked, thinking how, at twenty-nine, he looked so like his father at that age. Tall and sturdy, with the easy movements of a man comfortable in his own skin, and that watchful gleam in his eye, observing others with alertness but never with fear.

“Where to next, my boy?” old Anthony Cooke asked.

“Back to Moscow, sir, if the company can raise the funds. They’re refitting Spendthrift. I’ll be captain.”

Honor caught Richard’s dark look as he quietly left the room. Their son’s advancement was bittersweet. An expert navigator since he was twelve, Adam had been not just captain but master, too, aboard Richard’s ships for years, an equal alongside his father. But the storm off Cadiz four months ago that had sunk their two caravels with all their cargo—a massive, horrifying loss—had left them stranded on the brink of bankruptcy. Richard’s third, much older ship, Speedwell, lay moored in the estuary, derelict, for they could not afford to repair her. To bring in money, Adam had signed on with the Company of Merchant Adventurers. It pained Richard to see his son a mere hired seaman. It pained Honor to see their family breaking apart.

She slipped out of the room and found Richard starting up the stairs. To rifle through his account books again, she wondered, searching for phantom profits? Several nights she had gotten up and found him poring over the ledgers in candlelight. The futility of it—his obsession to ferret out some cash—tore at her heart.

“He’ll want to talk to you,” she said. “Richard, come back.”

He turned on the step. “He doesn’t need my advice. And words are all I can give him.”

“He’ll want to tell you everything. Let him give you that.”

He frowned. “Why don’t you wear the things I gave you?”

Instinctively, her hand went to her neck, betraying her.

“That’s right, your jewels. You never wear them anymore. Have you suddenly turned Calvinist? No more frippery?”

“There was so much to organize, the food, the wine, I . . . I just forgot.”

He looked at her for a long, sad moment. “I hope you got a good price,” he said, and went on up the stairs.

She stood still a moment, shaken. Not just at being found out. It was the change in him that unnerved her. She had never before seen Richard despondent. During everything they had lived through, he had always faced the challenges head on, alchemizing dangers and turning them to his advantage, whether outsmarting the bishop of Norwich’s henchmen or bedeviling the Church’s murderous inquisitors. It almost seemed that he’d thrived on it. But this—being unable to provide for his family—had unmanned him. Honor did not know how to help him.

When she rejoined her guests, Adam was rummaging in his burlap sack and pulled out a sleek, black pelt. The women gasped at its opulence, and Dorothy Hales exclaimed, “A sable!”

Adam draped it around Isabel’s throat. “From the forests of Russia, Bel.” She beamed as she stroked the silken fur. “And what do you think of this?” he said. He lifted out a carved wooden figure the size of his hand, a Russian peasant woman so plump she was pear shaped, with clothes and a kerchief painted in bright red and yellow and green. He set it in Isabel’s hand, then winked at her. “Watch.”

He pulled off the top half of the figure. Nested inside was a surprise: another figure, identical but smaller, a baby replica of the original. The guests cried “Ahhh” in delight.

“They call it a matroshka,” Adam said.

“From the Latin root, mater, I should think—mother,” John Cheke said helpfully. “What a quaint fertility symbol.”

Isabel turned scarlet, tears springing to her eyes even as she kept smiling. She pressed her face against Carlos’s broad chest as though to hide her embarrassment. He wrapped a protective arm around her, his face beaming with pride. “She was going to tell you later. Isabel is—”

“With child,” Honor blurted out. She’d guessed it the moment she saw Isabel’s happy tears.

Isabel turned back, sniffling and smiling, and nodded to her.

“When?” someone asked.

“Wedding night,” Carlos said, grinning.

Isabel playfully swatted his shoulder. “April,” she said.

“A little April fool, just like its mother,” Adam said, and before she could snap a retort he kissed her cheek.

Honor nudged past the guests and enfolded her daughter in her arms. “Oh, my darling.” She held Isabel so tightly it sent a stab of pain through her tender rib.

Isabel saw her flinch and quickly let her go, whispering, “I’m sorry, Mother.” She knew how near death that bullet had left Honor. “Are you all right?”

“Yes, yes, fine. And so very happy for you.”

The news of the baby sparked new life into the party and the guests threw themselves into eating and drinking with fresh gusto. Some bombarded Adam with questions about how the Russians lived, while others heatedly debated the Spaniards’ harsh rule in Peru, where Carlos was headed to captain the governor’s cavalry. And the dancing began. Honor wanted to hurry upstairs and give Richard the sweet news about the baby, but Henry Killigrew tugged her out to join the dance and was bowing to her to the strain of “Greensleeves” when Adam came to her side.

“Can I speak to you?”

His sober look was so at odds with his cheerful mood moments ago. What is wrong? Honor wondered. She excused herself to Henry and followed Adam to a deserted alcove behind the bowl of spiced wine.

“I’ve been round to the Kortewegs,” h

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...