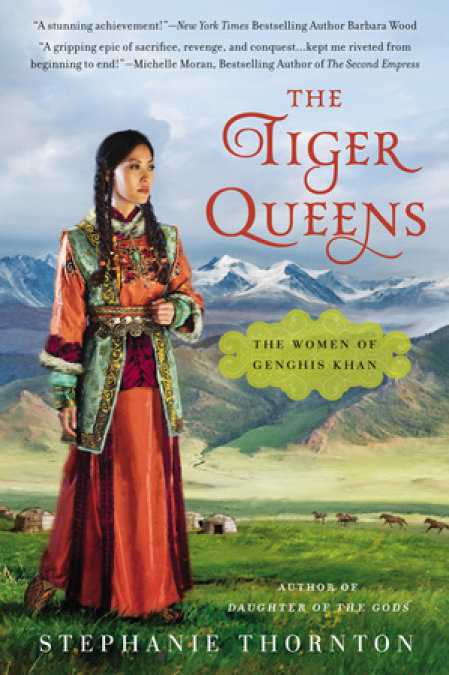

The Tiger Queens

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

In the late twelfth century, across the sweeping Mongolian grasslands, brilliant, charismatic Temujin ascends to power, declaring himself the Great, or Genghis, Khan. But it is the women who stand beside him who ensure his triumph....

After her mother foretells an ominous future for her, gifted Borte becomes an outsider within her clan. When she seeks comfort in the arms of aristocratic traveler Jamuka, she discovers he is the blood brother of Temujin, the man who agreed to marry her and then abandoned her long before they could wed.

Temujin will return and make Borte his queen, yet it will take many women to safeguard his fragile new kingdom. Their daughter, the fierce Alaqai, will ride and shoot an arrow as well as any man. Fatima, an elegant Persian captive, will transform her desire for revenge into an unbreakable loyalty. And Sorkhokhtani, a demure widow, will position her sons to inherit the empire when it begins to fracture from within.

In a world lit by fire and ruled by the sword, the tiger queens of Genghis Khan come to depend on one another as they fight and love, scheme and sacrifice, all for the good of their family...and the greatness of the People of the Felt Walls.

Release date: November 4, 2014

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 496

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Tiger Queens

Stephanie Thornton

ALSO BY STEPHANIE THORNTON

Prologue

Our names have long been lost to time, scattered like ashes into the wind. No one remembers our ability to read the secrets of the oracle bones or the wars fought in our names. The words we wrote have faded from their parchments; the sacrifices we made are no longer recounted in the glittering courts of those we conquered. The deeds of our husbands, our brothers, and our sons have eclipsed our own as surely as when the moon ate the sun during the first battle of Nishapur.

Yet without us, there would have been no empire for our men to claim, no clan of the Thirteen Hordes left to lead, and no tales of victory to sing to the Eternal Blue Sky.

It was our destiny to love these men, to suffer their burdens and shoulder their sorrows, to bring them into this world, red-faced and squalling, and tuck their bones into the earth when they abandoned us for the sacred mountains, leaving us behind to fight their wars and protect their Spirit Banners.

We gathered our strength from the water of the northern lakes, the fire of the south’s Great Dry Sea, the brown earth of the western mountains, and the wild air of the eastern steppes. Born of the four directions, we cleaved together like the seasons for our very survival. In a world lit by fire and ruled by the sword, we depended upon one another for the very breath we drew.

Even as the steppes ran with blood and storm clouds roiled overhead, we loved our husbands, our brothers, and our sons. And we loved one another, the fierce love of mothers and sisters and daughters, born from our shared laughter and tears as our souls were woven together, stronger than the thickest felts.

And yet nothing lasts forever. One by one, our souls were gathered into the Eternal Blue Sky, our tents dismantled, and our herds scattered across the steppes. That is a tale yet to come.

It matters not how we died. Only one thing matters: that we lived.

Part I

Chapter 1

1171 CE

YEAR OF THE IRON HARE

He came in the autumn of my tenth year, when the crisp air entices horses to race and the white cranes fly toward the southern hills.

A single man led a line of horses between the two great mountains that straddled our camp. Startled, I set down my milking pail and wiped my hands on my scratchy felt deel—the long caftan worn by men, women, and children alike—as my father joined me, grunting and shielding his eyes from the last rays of golden sunlight. Visitors and merchants often found their way to sit against the western wall of our domed ger, silently filling their bellies with salted sheep fat until our fermented mare’s milk loosened their tongues. I loved to hear their tales of distant steppes and mountain forests, of clans with foreign names and fearsome khans. My father was the leader of our Unigirad clan, but life outside our camp seemed terribly exotic to a girl who had never traveled past the river border of our summer grazing lands.

I finished milking the goats and untied them from the line, watching the shadows grow, eager for the trader’s stories that would carry me to sleep that night.

“Borte Ujin.” My mother, the famed seer Chotan, called from the carved door of our ger, her gray hair tied back and a chipped wooden cooking spoon in her hand. I hated that spoon—my backside had met it more times than I could count on my fingers and toes.

I was a twilight child, planted in my mother’s belly like an errant seed long after her monthly bloods had ceased. After being childless for so long, my parents welcomed even a mere girl-child, someone to help my mother churn butter and corral the herds with my father. And so I grew up their only daughter, indulged by my elderly father while my mother harangued me to sit straighter and pay more attention to the calls of geese and the other messages from all the spirits.

My mother was by far the shortest woman in our village, but the look she gave me now would have scattered a pack of starving wolves. “Pull your head from the clouds, Borte,” she said. “The marmot won’t roast itself.”

I lugged the skin bucket of milk inside, ducking into the heavy scents of animal hides, earth, and burning dung. The thick haze of smoke made my throat and eyes burn. The felt ceiling was stained black from years of soot, and the smoke hole was open to the Eternal Blue Sky, the traditional rope that represented the umbilical cord of the universe dangling from the cloud-filled circle. A dead marmot lay by the fire, the size of a small dog, with prickly fur like tiny porcupine quills. Our meat usually came from one of the Five Snouts—horses, goats, sheep, camels, and cattle—but my father’s eyes sparkled when he could indulge my mother’s taste for wild marmot. The oily meat was a pleasant change.

“There’s a visitor on the path.” I hacked off the marmot’s head with a dull blade and yanked out the purple entrails. My father’s mottled dog pushed at my hip with her muzzle, but I swatted her away, daring to toss her the gizzards only when my mother wasn’t looking.

Mother sighed and rubbed her temples, squinting as if staring through the felt walls at something far away. “I knew about the visitor before he stepped over the horizon,” she said, the beads that dangled from her sleeves chattering with her every movement. Each was a reminder of a successful prophecy breathed to life by her lips, bits of bone and clay gathered from the spine of the Earth Mother to adorn her blue seer’s robes.

I glanced at the fire. Two singed sheep scapulae lay on the hearth, cracked with visions of the future. My mother’s father had been a holy man amongst our people, but he had passed to the sacred mountains the night I fell from her womb. There were whispers that my grandfather’s untethered powers might have found a new home in my soul, and his Spirit Banner still fluttered in the breeze outside our ger, strands of black hair from his favorite stallion tied to his old spear, so that his soul might continue to guide us.

My mother stuffed the marmot’s empty stomach cavity with steaming rocks. “These strangers will bring great fortune and great tragedy.” She spoke as if commenting about the quality of our mares’ dung, then pushed a strand of graying hair back from her face and glanced at my palms, slick with blood. “You’d best not greet your fate with foul hands.”

My skin prickled with dread. My mother was an udgan, a rare female shaman, and had cast my bones only once and then forbade me from speaking of the dark omens to anyone, including my father. Lighter prophecies than mine had driven other parents to fill their children’s pockets with stones and drown them. And so I had swallowed the words and promised never to speak of them.

The Eternal Blue Sky was bruised black when I stepped outside, and the scent of roasting horsemeat from a nearby ger made my stomach rumble. The water in the horses’ trough clung to the warmth of the day and I scrubbed until the flesh of my hands was raw. As on any other night, voices floated from the other far-flung tents. My cheeks grew warm at the grunts of lovemaking from the newly stitched ger of a couple freshly wed, the young man and woman who my mother claimed mounted each other like rabbits. The moans were muffled by a new mother crooning to her fussy infant and an old woman berating her grandsons for tracking mud into her tent.

And my father’s voice.

I started toward him but retreated into the shadows as a wiry stranger stepped into view. About the same age as my father, the man wore two black braids threaded with gray hanging down his back, topped with a wide-ruffed hat of rabbit fur. Five dun-colored horses grazed in the paddock, laden with packs, their dark manes cropped close. I strained to hear the conversation, but my father only complimented the man on the quality of his animals. The stranger patted the flank of a pretty mare, releasing a puff of dancing dust into the air. Early moonlight gleamed on the curved sword at his hip, an unusual sight amongst my peace-loving clan, but then the light hit his face. I stumbled back, nearly landing on my backside.

His right eye glittered like a black star, but the left socket was empty, a dark slit nestled between folds of wrinkled skin and at the exact center of a long white scar, likely an old battle wound.

“And I thought they called you Dei the Wise.” The man grinned at my father, revealing two lines of crooked brown teeth. “You didn’t think I’d come without something to trade this time, did you, Dei?”

This time. So my father knew this traveler.

I thought to stay and listen, but the stranger shifted on his feet and his gaze fell on me. I expected a one-eyed scowl, but instead the man’s bushy eyebrows lifted in surprise.

I shrank further into the shadows, pulling the darkness around my shoulders. My mother would have my skin if she knew I’d been eavesdropping. Learning more about this stranger would have to wait until he’d filled his belly with our marmot.

I scuttled back to our ger, feeding the fire with dried mare dung until it crackled and my cheeks flushed with heat. My mother bustled about, mumbling to herself as she set out five mismatched wooden cups.

“There’s only one visitor, Mother.”

She ignored me and poured fresh goat milk into two cups, then filled the other three with airag. I knew better than to argue what I’d seen with my own eyes.

My mother pulled the rocks from the marmot’s belly as the wooden door opened, ushering in a gust of cool air along with my father and his guest. Behind the man skulked a scrawny boy scarcely my height, dressed in the same ragged squirrel pelts as his father and fingering the necklace at his throat, a menacing wolf tooth hung from a leather thong. His black hair was cropped close to his head and his eyes gleamed the same gray as a wolf’s pelt. My father’s dog gave a happy bark and jumped up, paws on the boy’s shoulders as if embracing a lost friend. The boy’s hand went to the hilt of his sword, a smaller version of his father’s, and for a moment I thought he might stab the dumb beast. I dragged her away by the scruff of her neck and forced her to sit at my feet, prompting a raised eyebrow from the boy.

I turned my nose up at him and looked to the one-eyed visitor as he bowed to my mother. At least the father had manners.

“Chotan,” he said to my mother, straightening. “I bear warm words from Hoelun, my first wife and mother of my eldest son.”

My mother grasped the wooden cooking spoon so hard I thought it might crack. It took me a moment to recall the story of my mother’s childhood friend Hoelun, married to a handsome Merkid warrior who loved her. The story of her shame and dishonor while en route to her new husband’s homeland was still whispered around hearth fires, that a desperate Borijin hunter had been tracking a rabbit when he came across a splash of fresh urine in the snow, left by a woman. The man ignored the rabbit and hunted the woman instead, stealing her from her husband and claiming her as his wife.

A one-eyed hunter.

This man wearing a sword curved like a smile was no exotic trader, but instead a kidnapper of women.

The fire suddenly burned too hot, yet a cold sweat broke out on the back of my neck. I stepped toward my mother, well away from the men’s side of the tent. “And this must be your daughter,” he said, opening his arms toward me. “Her face is filled with the first light of dawn, yet her eyes are full of fire like the sun.”

It wasn’t my eyes that filled with fire then, but my cheeks.

“Borte’s soul is full of fire,” my mother snapped. “As was Hoelun’s.”

“Still is,” the stranger said with a laugh. “Fiery women make the best wives.” He elbowed the black-haired boy, still standing sullenly at the edge of the ger. “They’re certainly the best in bed.”

At least I wasn’t the only one with burning cheeks. The boy looked as if he wished the Earth Mother would open her maw and swallow him.

My father cleared his throat and handed the largest cup of airag to his guest. “You must be thirsty after so long a journey, Yesugei. Rest a while and then you can tell us why you’ve come.”

The men stuffed their bellies with so much marmot that my stomach still rumbled when I lay on my pile of furs later, listening to Yesugei’s wild tales. His son hadn’t yet spoken, only sat on the visitors’ west side of the tent as if forgotten by his father and crammed his mouth with marmot as if he might never eat again. His gray eyes darted about, no doubt taking in everything. I burned to know why this one-eyed man dared return to the village of the woman he’d kidnapped, but the heat of the fire pulled me into sleep. The furious whispers of my mother and father entered my dreams, but the rosy fingers of day pushed their way through the cracks of the ger when I next opened my eyes.

I wished I hadn’t woken when I heard what the men were discussing.

“Temujin would make Borte a good husband,” Yesugei said.

Temujin. So that was the boy’s name. It meant to rush headlong, like a horse racing where it wished, no matter what its rider wanted. He sat cross-legged by the door, sharpening a stick with a wicked-looking knife as his foot twitched. I had a feeling he was ready to bolt at any moment, to saddle a horse and tear across the steppes.

I might beat him to it.

“They’re too young.” My mother’s voice stung like a wasp. I peered through slitted eyes to see my father lay a gentle hand on her arm, the platter of dried horsemeat to break our fasts untouched between them. “I’ll not give the only treasure of my womb to a Tayichigud raider,” she muttered.

I wondered then if she wished she had told my father our secret instead of keeping it hidden all these years. Now it was too late.

“Since the days of the blue-gray wolf and the fallow deer, the beauty of our daughters has sheltered us from battles and wars. Our daughters are our shields.” My father’s words were an oft-repeated maxim amongst our Unigirad clan, yet Yesugei’s people were well-known as the lowest and meanest of the steppe’s families, as sharp clawed and sneaky as battle-scarred weasels. No single man ruled the grasslands, meaning that the belligerent Merkid, wealthy Tatars, fierce Naiman, and even the Christian Kereyids all fought continuous wars for supremacy.

“Borte,” my father said in a stern voice, but I kept my eyes closed. “Stop feigning sleep and come here.”

I sat up and my mother handed me a cup of goat’s milk to wash the bitter taste of sleep from my mouth, but I found it hard to swallow.

“I’d keep my little goat with us as long as possible, forever if I could.” My father twirled a strip of dried meat between gnarled fingers, then sighed. “But as much as I might wish it, it is not my daughter’s fate to grow old by the door of the tent she was born in.”

“My husband,” my mother said. “It is not wise—”

My father didn’t allow her to finish, only raised his hand for silence.

“I don’t wish to be married,” I said, praying the Earth Mother would send up roots from the ground to bind me forever to this ger. I had no desire to be saddled to the half-wild son of a barbarian raider. Surely my father would not match me to a boy so far below us, and thereby banish me to the farthest and most barren expanse of the steppes.

“One day I’ll give you my daughter, to keep the peace between our clans,” my father spoke over my head to Yesugei, his hand on my shoulder. I had no doubt that Yesugei might steal what he wanted, as he’d done before with Hoelun, thereby disgracing me forever. I waited for my father to nudge me forward, yet he didn’t move. “But that day is not yet born.”

I stared up at him, only then noticing the tick of blood fast in the vein on his neck. “Instead,” he said, “I invite you to leave Temujin with us for a while, to hunt and herd for me so we can get to know our new son.”

Yesugei gave a bark of laughter and clapped the boy on his back, grinning as if he’d just returned victorious from a raid on a neighboring village. “Do you hear that, boy?” he asked. “I just gained you a wife!”

In that moment I wondered if all girls’ hearts curled up in their chests and their knees threatened to give way upon hearing the news of their betrothals.

Many cups of airag later, Yesugei swung up unsteadily onto his horse’s bare back, then dropped the rabbit-fur hat onto Temujin’s head. “I leave my son to you,” he said to my father, then straightened and glanced at his boy. Temujin bore traces of his father in his bushy brows and the wry twist of his lips, but they differed in the set of their jaws and the slant of their eyes. I wondered if he favored his mother instead, or some ancestor long since passed to the sacred mountains. Yesugei circled his son on horseback, then bowed to my father. “I fear you’re not so clever as they say, Dei the Wise, for I have gotten the better end of this deal.” He turned his horse to leave, then called over his shoulder, “And you should know, this whelp of mine is frightened by dogs.”

Then Yesugei trotted away with his string of horses, heading back to his people, leaving behind a single dun-colored filly as a gift to my father, and a black-haired boy with a scowl like a storm.

My future husband.

* * *

Orange clouds streaked the sky that night and the air was so chilled that I jammed my favorite hat—tattered leather with ugly earflaps—over the snarls in my hair before going out to milk the mares. We had quickly learned that the filly left behind by Yesugei was an ill-tempered beast; I’d already been kicked trying to mount her. My father had only shaken his head and sighed. “I should have expected as much from Yesugei the Brave.”

I had hoped my father might send Temujin away after such a slight, but instead he made space for Temujin’s bed on the men’s side of the ger. The boy’s blanket was still rolled up, as if he was prepared to flee at any moment.

How I wished he would.

I knew in my heart that I should thank the Earth Mother that Temujin wasn’t older than my father, fat, and toothless, with a passel of snot-nosed children from other wives, old women who would box my ears and make me gather horse dung until my back broke. At least Temujin’s teeth were mostly straight and his skin was smooth—even if he was younger than me and his features seemed permanently etched into a glare. All women married, and I would be Temujin’s first wife, the position of honor girls daydreamed about and women fought for.

But I didn’t thank the Earth Mother. Instead, I cursed my father for promising me to the son of a one-eyed thief and my mother for not trying harder to stop him. And then it occurred to me—perhaps if Temujin knew what I did about my future, then he would no longer want me. For the first time I considered breaking my oath of silence to my mother.

I looked to the Eternal Blue Sky for a sign, yet the spirits were stubborn that night and the skies remained empty, without even a breeze to hint at the path I should take.

I had just come from telling my friend Gurbesu about my betrothal and my ears still rang with her shrieks of glee. Now I craved the quiet murmur of the river before returning home for the night. I emerged from the forest of tents and gasped at the sight before me. Temujin sat on the back of the dun-colored filly, his fists wrapped tight in the black mane and his ankles digging into the horse’s sides as it attempted to throw him. He leaned back just enough that it was impossible to tell where beast ended and boy began. I waited for him to fly into the fence, pondering whether I’d leave him in the dirt or help him up, when the mare slowed and trotted in a circle around the paddock. Temujin grinned then, an expression of such unfettered joy that I knew he thought himself alone.

He saw me when the filly rounded the bend. I took some satisfaction as his eyes widened and he released the horse’s mane to run his hands over his closely shaved scalp. The breeze ruffled the hem of my deel, carrying a whiff of my scent to the horse.

In less than a breath, she reared up and deposited Temujin on his rump in the dust. The animal snorted and cantered off, flicking her tail and dropping a pile of fresh manure on the packed earth.

Temujin scrambled up and glowered at me. “You startled her.”

“So you do speak.” I’d expected his voice to be that of a boy, but it already bore the deep tone of the man he would soon become.

“Of course I speak,” he said, brushing off his trousers. “Did you think I was mute?”

The thought had crossed my mind; after all, he’d done no more than grunt during the betrothal ceremony. I shrugged and folded my arms in front of my chest. “You shouldn’t be riding that horse.”

“Why not?” He bent his skinny arms to mirror me, then nickered to the filly. “She’s mine.”

“No, she’s not.” Then the realization filled my mind. “Your father left us your horse?”

He shrugged. “He would never leave behind anything of value.”

Still, he’d left Temujin behind, although his worth had yet to be measured. Yesugei was even slipperier than we’d expected. “She’s not even broken.”

“My father couldn’t break her. That’s why he gave her to me.” He called to the horse again. The filly’s ears flicked as if at a buzzing fly, but then she trotted toward us. “It was either that or eat her.”

Temujin vaulted onto her empty back and offered me a hand up. His hands were square and squat, much like the rest of him.

“I prefer not to break my neck,” I said.

“She hardly ever throws anyone.” He grinned, the expression transforming his young face. “At least not if you hold on tight.”

I ignored his hand, knowing I should leave, but instead I grabbed a fist of the horse’s mane and mounted behind him. The filly startled and sidestepped for a moment, but Temujin didn’t give her a chance to think. Instead, he kicked his heels into her ribs, sending her bolting straight toward the paddock’s rickety spruce log wall.

The scream that tore the sky came from my own throat; the paddock was built so tall that no horse could clear it. Yet with Temujin’s urging in her ear, the dun-colored filly leapt into the air, arcing over the fence and landing with a jolt so hard my teeth almost cracked.

And then we were tearing out of camp, racing past slack-jawed boys bringing in their goats and old men huddled together trading even older hunting stories. I thought I glimpsed my father, but I blinked as my eyes watered at the speed. I clutched Temujin’s bony ribs, feeling my hat fly away and my hair tumble loose behind me.

And then I laughed. Never before had I dashed barebacked over the steppes like this, scattering grasshoppers and racing the cranes overhead.

Temujin’s voice joined mine and he urged the horse faster. Only after the filly’s pace began to lag did he rein her in. The gers of my camp were tiny dots on the horizon, white cotton flowers in the distance.

“So you can laugh,” he said over his shoulder, mocking my earlier words. The filly ignored our conversation, more interested in the grass at her feet.

“Of course I can laugh,” I said, making a face at the back of his head.

Temujin seemed much easier now that his father was gone, as if every step Yesugei took away from our camp lightened his son’s heart. I wondered if the same would happen once I left my mother’s tent, but the very thought was like a weight pressing against my chest.

“One day I’ll be khan of my clan,” he said. “I’ll have a whole herd of horses like this one. Sheep, goats, and camels, too.”

“What, no yaks?”

He laughed. “Maybe a few yaks.”

I let my arms hang loose, noting the worn leather of his boot and the countless places where it had been stitched with sinews of various colors and ages. Many boys before him had probably worn the same shoes. I wondered how hard his life had been, how difficult mine would be once we were married. “Your father must be a good herder to be able to spare his eldest son.”

I knew even before his spine stiffened that it was the wrong thing to say. “My father is a terrible herder,” he said. “But he’s an excellent raider.”

I searched for something to say. “I suppose that takes skill as well.”

Temujin glanced back at me again, then laughed. “Are you always so polite?”

“Are you always so rude?” I scowled, but he didn’t seem to mind. “I should return home,” I said. “My mother will be wondering where I am.”

I feared he would argue, but then he urged the filly into a trot toward camp, forcing my arms around him again. “My father told me before he left that I should be pleased to have such an obedient wife,” he said. “I held my tongue.”

“You don’t care for an obedient wife?”

“I think you’re like this filly. You only act obedient,” he said, “because you don’t want anyone to see your true nature.”

I let my hands drop completely then, preferring to take my chances on being thrown than to touch him a moment longer. He felt my anger and glanced over his shoulder.

“I meant that as a compliment,” he said, his voice quiet. “I think there’s more to you than you show the world, Borte Ujin.”

“You don’t know anything about me.”

“I know you don’t want to marry me.”

I sighed, wishing I was gathering stinging nettles or lancing a boil on my mother’s foot. Anywhere but here. “No, I don’t want to marry you,” I finally said.

“Because I’m coarse, rude, and beneath you in every way that matters.” His voice was angry, but his shoulders slumped under the weight of his words.

He spoke the truth, but I didn’t care to injure him further. My mother’s warning filled my mind, the words that had sworn me to secrecy years ago. There seemed so many reasons to tell him the prophecy, and so few to keep the truth hidden any longer.

I shifted behind him, unable to find comfort. “No, there’s something else,” I said, each word drawn out. “My mother cast my future when I was born.”

“So did mine,” Temujin said. “I was born with a blood clot held tight in my fist. My mother claimed the sign meant I was destined for greatness.”

I smiled sadly, glad he couldn’t see my face. “She may be right.”

Temujin seemed to sense my melancholy. “What was your prophecy?”

I hesitated, prompting a low chuckle from deep in his chest. “Consider who my father is, Borte Ujin. Nothing you can say will shock me.”

Still the words lodged like stones in my throat. Temujin deserved to know the truth if he thought to marry me one day. Or perhaps he might abandon me now and avert the whole tragedy.

“My mother cast my bones while bits of her womb still clung to me and blood ran down her legs.”

“And?” Temujin’s hand covered mine and he pulled it to his chest, as if giving me the strength to speak the words.

“I will cleave two men apart and ignite a great Blood War that will rain tears and destruction upon the steppes.” The words tasted like ash in my mouth, and my mother’s warning echoed in my ears. Suddenly it was difficult to breathe, as if giving voice to the terrible words had cost me more than I knew.

Temujin covered my arms with his, his fingers weaving between mine in the filly’s mane. I leaned forward, letting my head rest on his back and daring to breathe deeply of his scent. “I battled a wolf once to get this tooth,” he said, his bones vibrating with the sound as he touched my fingers to the necklace at his throat. “You can

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...