- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

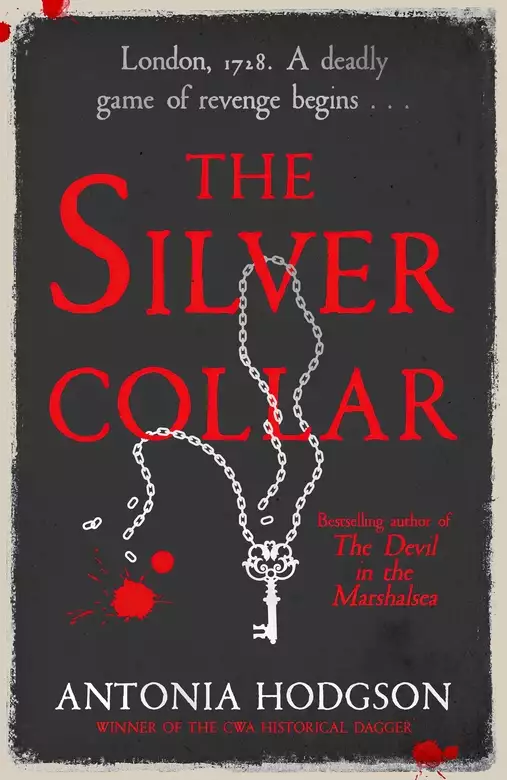

The fourth novel in Antonia Hodgson's award-winning series featuring Thomas Hawkins and Kitty Sparks is at once her most thrilling and the most darkly disturbing story yet.

The next rip-roaring thriller from Antonia Hodgson, featuring Thomas Hawkins

Autumn, 1728. Life is good for Thomas Hawkins and Kitty Sparks. The Cocked Pistol, Kitty's wickedly disreputable bookshop, is a roaring success. Tom's celebrity as 'Half-Hanged Hawkins', the man who survived the gallows, is also proving useful.

Their happiness proves short-lived. When Tom is set upon by a street gang, he discovers there's a price on his head. Who on earth could want him dead - and why?

With the help of his ward, Sam Fleet, and Sam's underworld connections, Tom's investigation leads to a fine house in Jermyn Street, the elegant, enigmatic Lady Vanhook and an escaped slave by the name of Jeremiah Patience.

But for Tom and Kitty, discovering the truth is only the beginning of the nightmare.

A powerful, deeply immersive thriller, The Silver Collar is both a celebration of love and friendship, and a terrifying exploration of evil.

(P) 2020 Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

Release date: August 6, 2020

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Silver Collar

Antonia Hodgson

Winter, 1728

Jeremiah Patience begins his journey in darkness, far to the east of the city. He walks with his shoulders rolled, in a thin coat made for a milder season. It is mid-November, and bitter: the wind as sharp as a blade. This is his third winter in England, each one colder than the last. His lips are chapped and his toes throb with chilblains.

He walks, and the city wakes around him, bolts drawn back, candles gleaming in garret windows. This is the hour of servants and street sellers, rising before dawn with tired faces and smothered yawns.

A nightwatchman trudges wearily up the road towards him, lantern pole balanced on his shoulder. Jeremiah lowers his hat and tugs his neckerchief until it covers his mouth. The gesture makes him feel like a villain in a play. He starts to sweat, despite the cold.

It is no theft, he reminds himself, to take what is mine.

Jeremiah studies the watchman closely as he approaches. His vigilance is a legacy of his life on the plantation. Even in quiet, drifting moments, some part of him always remains alert to trouble. I should be the one called watchman. A brief, darting look is enough for him to read the man’s expression. Indifference – weary indifference. A man with sore feet, who wants only to collapse upon his bed, and have his wife take off his heavy boots for him. But still Jeremiah holds his breath, until the watchman disappears around the corner.

Quiet roads and alleyways now, all the way to Jermyn Street and a house with a green door – so dark a green it could be black. The knocker is a lion’s head, lips pulled back in an iron snarl. He is tempted to walk up and knock. More than tempted – he has to grip the railings to stop himself. He has waited three years for this day. He can wait a little longer.

A cart turns on to the street. He puts his hands in his pockets and follows in its wake, head down, scouting for a place where he might watch the house unseen. A narrow alleyway leading to the Bell Inn suits his purpose. Two ancient beggars lie stretched out at the alley’s mouth, side by side as brothers. He offers them a farthing and joins them on the damp cobbles, breathing through his mouth until he grows accustomed to the smell. London stinks, even on Jermyn Street: it still surprises him.

He watches and waits.

It is past noon when a chair arrives at the almost-black door. The street is busy – it is not ideal, none of this is how he’d hoped it would be. But since when has life been ideal? He stands, his legs cramped from long hours of sitting, and crosses the road. His chest thrums with anticipation. So close.

The chairmen settle the sedan to the ground and stretch their backs and shoulders, roll their wrists. One says something and the other laughs. German, Jeremiah decides. He has an ear for languages, for their cadence, hears scores of them at the docks.

The door opens and a woman steps out in a fur-trimmed riding hood. She is followed by a servant, a sturdy fellow with a rough complexion, dressed up in gold buttons and lace. The finery doesn’t suit him, and he knows it. His face is set in a rigid mask, barely concealing his ill-humour.

There are worse punishments, Jeremiah thinks. And in the next instant forgets the servant entirely.

A young black girl steps out carefully in new shoes. Her tight black curls are wrapped in a stretch of orange silk, finished with a peacock feather. Around her throat, a wide silver collar.

Jeremiah’s heart lifts and opens out to fill the world. Affie. Affiba. He breathes her name and the word forms a cloud in the freezing air.

She is no more than ten paces away.

Jeremiah’s plan is simple: pick Affie up and run. She is small for her age, and delicate (she was not delicate once, what have you done to her?); she will be light in his arms.

No one has noticed him yet. There is no need to say anything.

He needs to say something.

The conflict squeezes his heart.

Take her and run.

Speak. Speak.

This is what he wants to say to the woman in the fur-lined riding hood:

Lady Vanhook – do you remember me? I am alive: do you see? I am alive. I have come to take back what you stole from me.

His tongue falls heavy in his mouth, his throat closes around the words.

She looks at him, then. No, he is mistaken – she looks through him. He is a stranger, a ghost, air. Nothing. She smiles, vaguely, and permits her servant to guide her into the chair, gloved fingers curled over his hand. Such elegance, such grace. Such wicked charm. He remembers it all now and it chills his blood, colder than the ice wind. She is Medusa and he is transformed to stone.

I have made a mistake, he thinks. A dreadful mistake. His simple plan, which had seemed so safe and sensible back home in his Limehouse lodgings, now feels like dangerous folly. What if the chairmen chases after him? What if the servant has a pistol tucked beneath all that silk and lace? What if Affie were hurt? He cannot risk her life, or his own. If he is killed, who will save her?

I cannot do this alone.

The truth hits him like a fist in the stomach. To be so close . . .

He must retreat – but he cannot move.

Affie, oblivious, steps into the chair, still admiring her new shoes. Lady Vanhook lifts her on to her lap, wrapping her arms around the girl’s tiny waist. The chairmen pick up their poles.

Three years he has waited for this moment. Now he is trapped within it.

He fights – and at last two words escape from his throat, like birds.

‘Affie. Daughter.’

No one hears him. They are gone.

Chapter One

Six weeks earlier

We had no warning, Kitty and I, of the troubles to come. It had been a quiet summer – golden and easy after months of violence and threat. When the hot stink of the city became too much to bear we left it behind, renting a house in the country at Greenwich. Our days were spent on the river, on the bank, in bed. In stolen, solitary hours I completed my account of our trip to Yorkshire, and when my quill summoned old ghosts and bad memories I strode into the yard and pounded a sack of corn until my knuckles bled. It was, as I say, a peaceful time.

In early September we returned home to Covent Garden, and to Kitty’s bookshop, the Cocked Pistol – an establishment of such ill repute that a brief glance through its window could tarnish the soul. Half the town loved it, the other half wished it burnt to the ground. And half of the half who wished it burnt to the ground secretly wished no such thing, sidling in when the shop was quiet to buy armfuls of filth. We liked hypocrites at the Pistol – they were some of our best customers.

Over the summer, Kitty had devised a new stratagem to increase the shop’s profits. She was very much a planner, one might even say a schemer – constantly searching for ways to improve her business. The reason for this was no mystery.

Kitty had been born into middling wealth, the only child of Nathaniel Sparks, a respected physician, and his wife, Emma. Then, when she was thirteen, her father died. Her mother – through a mixture of greed and bad choices – frittered away the family fortune in less than a year. Imagine the misery, the profound shock of such a swift fall from comfort to destitution. I say imagine, as Kitty refused to speak of it. I knew that she had been forced to abandon her mother, in order to survive. I knew also that Emma Sparks had died a lonely, squalid death, selling her body on the streets. But I had not learnt this from Kitty.

This much she would tell me: the night she ran away from her mother, she vowed she would never rely upon another soul again. She would be her own mistress, forge her own path through life. And the next time Fate came to ‘kick her up the arse’, she would be ready to kick back.

Which returns me to her stratagem for the Cocked Pistol.

Kitty had been inspired by the frontispiece of our most popular book, The School of Venus, in which a clique of goodwives clustered around a market stall festooned with dildos. We sold the book faster than we could print it, so why not the objects themselves?

From here it was a mere half-step to condoms, whips and medicines for the pox – desire, fulfilment and consequence, all under one roof. Kitty insisted upon the best quality and charged accordingly. Her condoms were made from sheep’s gut instead of the inferior pig’s bladder and were guaranteed fresh and never previously used. Her fine leather dildos were available in diverse sizes from the modest to the alarming. She placed advertisements in the newspapers, kept the shop open until eight o’clock at night, and within a month had increased the Pistol’s profits fourfold. In short, the venture was a triumph. Kitty was richer than ever.

I – alas – was not, having been stripped of my inheritance some years before, following a regrettable* incident at an Oxford brothel. I had perhaps eight pounds to my name, a watch with a stranger’s initials engraved into the case, and a reputation for trouble. Why Kitty loved me was a mystery.

*not entirely

‘For his legs,’ she laughed, when we were in company.

‘For your cock,’ she breathed in my ear, as she pulled me upstairs to bed by my breeches.

‘For your heart, Tom,’ she murmured, late at night, only half awake in my arms. ‘I love you for your heart.’

Being a great planner, Kitty was very keen on lists. Sometimes she would count things out upon her fingers, sometimes she would turn a group of chores into a little song (‘today we wash the sheets, tra la, today we scrub the floors, tra la’ et cetera), and sometimes she would write a list IN CAPITALS and pin it to the wall. These TERRIFYING LISTS were always addressed to me, THOMAS HAWKINS, and involved things I had PROMISED TO DO MOST FAITHFULLY, and yet somehow, dearest, they were not done, NOT AT ALL, not even VENTURED.

So I would not be surprised if Kitty had pondered the question Why do I love Tom? (perhaps after I drank that quart of brandy and mistook her hat for a chamber pot) and decided to write down the reasons:

Q. Why (on earth) do I love Tom?

i) Legs

ii) Cock

iii) Heart

While I would not argue with her answers – one certainly wouldn’t wish to see any of them removed – I could not help feeling the list was rather short – desultory, even. I mention this because it dissatisfied me, at the time. I remember thinking, Tom, you really must find something to add to this list, because those three items are not enough, she will grow tired of you, you will grow tired of yourself, Kitty is now a very rich woman who refuses to marry you because she will not be dependent upon anyone, and because she thinks – for some mysterious reason – you will gamble away her fortune.

My point is that while I was fretting over such nonsense, I failed to notice the one thing that mattered: we were happy. Other people had noticed, however – and they were most decidedly not happy. Envy snaps its teeth at the heels of good fortune, and there is nothing in the world more destructive than a man who wants what he cannot have.

Our troubles began on Sunday 13th October, 1728. I remember the date because of what followed, but also because of what preceded it. Kitty and I had met the previous autumn, when I was tossed into the Marshalsea prison for debt. I almost died in that hellish place, and while I was recovering, my oldest friend, Charles Buckley, told me that Kitty was dead. He thought he was saving me from a shameful liaison – Kitty was a servant at the time, and I was a gentleman (disgraced, but no matter). I mourned her for weeks, while she thought I had abandoned her.

We were reunited the day after the coronation, 12th October, 1727, just after nine o’clock in the evening, at Moll’s coffeehouse in the piazza, by the fire. Seeing Kitty alive and well (and furious with me, but never mind), remains the happiest and best moment of my life.

Kitty and I decided to mark the occasion by returning to Moll’s a year later to the very day. I had intended to propose to her by the fire, as the clock struck nine, but on our way to the coffeehouse Kitty squeezed my hand and said, ‘Darling Tom, please don’t ask me to marry you tonight, I shall only say no and you will sulk and it will ruin the evening.’ I assured her the thought had not entered my head.

Our table was waiting for us by the fire, and the first bowl of punch was on the house. Kitty and I toasted one another, and made bets over which gang of drunks would start the first fight. Moll’s had a wicked reputation, which drew a particular crowd – men craving spectacle, riot and debauch.

Not that anyone would dare start a fight with me. Six months ago I had been found guilty of murder and sent to hang at Tyburn. I had long since proved my innocence, and received a royal pardon – but my reputation went before me, as the saying is. I was Half-Hanged Hawkins – the man who died upon the gallows and was then returned to life. When I walked into Moll’s that evening, men stared and nudged one another. Whether they considered me a miracle or something much darker, they certainly did not wish to provoke me. This awe and wonderment would surely fade in time, but I was content to rely upon it while it lasted. I had spent ten minutes choking on that damned rope, legs kicking the air while the crowds cheered me to my death. If I gained some benefit from that, I had earnt it a thousand times over.

‘I shall buy you a pie,’ I shouted over the din.

‘Not from here,’ Kitty said, alarmed.

‘Heavens no.’ I wished to treat her, not poison her. I sent a boy out to Mr Kidder’s pie school at Holborn. Within the half-hour he returned with trout pie, fried oysters and a beef pasty. Watching Kitty eat, I felt very pleased with myself. How many women could boast that their (almost) husband not only remembered the anniversary of their union, but bought them supper to celebrate? A lucky handful at best, I would wager.

When the clock struck nine we raised another toast to ourselves, and then another, and Kitty sat upon my lap and kissed me, as she had done a year ago, and then I may have fallen asleep at some point, as I had also done that first night. I certainly remember Kitty digging me in the ribs as if to wake me, and saying we must go home, as she had a present for me.

Assuming this was code for some wickedness in the bedchamber, I jumped up from my chair at once. But when we arrived at the Pistol she presented me with an ebony walking stick, its gold top shaped like a fox’s head, with twin emeralds for eyes.

‘Kitty,’ I said, dismayed. ‘This must have cost . . . I have not bought you anything.’

‘You bought me a pasty,’ she said, and hugged me. ‘I love you, Tom.’

I assured her that I loved her too. ‘But this is too fine a gift.’

Her face fell. ‘If you do not like it . . .’

‘No, no.’ I gripped it tight, and as I did so the gold head separated from the stick. The ebony cane was in fact a long case, housing a narrow steel blade. The fox head was the blade’s handle. A swordstick. I swished it through the air, appreciating the quality. I had never seen its like. I felt strange and almost shabby accepting a gift of such value, but Kitty looked so pleased with it, and so anxious that I liked it, that I smiled, and swished it again before sheathing it back in its ebony case. Naturally this led to a joke about where I should like to sheath my own sword. It was not very funny, but we had drunk those two bowls of punch at Moll’s, and a further bottle of claret.

In any case, we went to bed laughing.

Chapter Two

The next morning – the day everything changed – began pleasantly enough.

I was perched upon a high stool in the shop, pretending to read a novel. The Pistol was closed, it being a Sunday, but Kitty was still hard at work arranging books and pamphlets, her copper curls pinned neatly beneath a clean white cap. She kept the openly lewd and seditious works hidden away, while those displayed upon the shelves were more subtle, disguised as volumes of anatomy, medicine, and firm moral correction. I watched her surreptitiously from behind my copy of Love in Excess. Watching Kitty work was one of my favourite pastimes – she was so clever and quick, bending and stretching in a most diverting fashion.

She left the window and moved towards the counter where I was sitting, wiping her hands upon her gown. Her freckled face was flushed red with exertion, and I caught a trace of sweat beneath her perfume as she came nearer. She had bathed in lavender water this morning. I thought of her, bathing. Steam rising from smooth, snow-white skin. The lapping of the water as she moved her legs. Her fingers tracing up her thigh—

‘Tom, dear heart, have you moved once this morning? Will you not mend the floorboard on the landing today? You promised you would.’

I slid from the stool, as if to leave, then caught her wrist and drew her close, pressing my hips to hers. ‘I can think of more urgent business,’ I said, nuzzling her neck.

She sighed, and trailed a hand beneath my shirt. ‘Tom,’ she murmured in my ear. ‘The floorboard.’

Damn it.

She pinched me. ‘Do you think me so easily distracted?’

‘Of course not, sweetheart. But you have worked so hard this morning. You deserve a rest, don’t you think?’

Kitty knew what I was about, but she did not particularly mind. I kissed her again, pulling off her cap and grabbing her hair, until we were lost in each other, falling to the floor in a tangle.

I lifted her skirts to her waist and kissed my way up her legs, pulling her stockings down so I might taste her skin. The scent of lavender and the scent of her. Heaven. I licked the soft velvet of her inner thigh in light circles, teasing. Higher. Closer. ‘Should I stop? The floorboard . . .’

‘No!’

She tilted her hips and I slid my tongue inside her. She moaned in pleasure, arching her back.

I pushed deeper, in and out, tongue, fingers, tongue. ‘Do you want me?’

‘Yes. Yes.’

There was a sharp knock at the front door.

The mood, I must say, was spoilt.

Kitty snarled in frustration, then pushed her skirts back in place as I rolled free.

‘Open up!’ a voice called through the door. Then more knocking. ‘Open up at once!’

I put my finger to my lips, then crept over to the rain-spattered window. A man of late-middling years stood upon the doorstep with three guards, tapping his foot in a show of irritation. He was dressed in an old-fashioned grey coat and long, heavy brown wig.

Oh, Lord.

‘Who is it?’ Kitty shoved on her cap and crawled over to the window to take a look. ‘Gonson.’ She spat his name, as if it were a curse.

Sir John Gonson, magistrate for Westminster, hated me with a burning, holy passion. He more than anyone was responsible for my trip to the gallows, turning the town against me and testifying at my trial. Did he apologise for this, when I was proved innocent? Show any remorse? Of course not. But we had not suffered a single raid upon the shop since my pardon. I had dared hope he would not bother us again.

I felt a familiar ache between my shoulder blades, a warning of trouble ahead.

‘What does he want?’ Kitty muttered.

‘Perhaps he’s in need of your mercury pills.’

She stuck out her tongue, disgusted by the notion of Gonson fucking anyone, never mind contracting something unpleasant from them. And then we sniggered together like children.

Unfortunately one of the guards heard us. He scowled through the misted window, then rapped on the pane with his knuckles. ‘Open up, or we’ll break the door,’ he shouted, his voice muffled through the glass.

There was nothing to be done but to stand up, and let them in.

Gonson strode into the shop, nose in the air.

‘Sir John.’ I bowed low, with a deep flourish. I am very good with a satirical flourish, it is one of my great talents. ‘An honour to receive you in our modest home, sir. Might I offer you some wine? A bowl of coffee?’

He pursed his lips – Persephone, refusing nourishment in the Underworld. ‘I am here on a matter of business.’

‘Working on the Sabbath? Should you not arrest yourself?’

Gonson reddened. ‘God’s business, sir.’

By which he meant the Society for the Reformation of Manners, which was growing ever more powerful under his watch. The Society’s great mission was to rid the streets of sin, most of all that dread quartet of drinking, swearing, gambling and whoring. For Gonson and his friends, London was a latter-day Sodom, its citizens drowning in a putrid stew of vice. No transgression was too slight, in their eyes: a muttered ‘God damn’ over a stubbed toe must lead, inexorably, to damnation.

This was why Gonson hated the Pistol, and wished to destroy it. In his narrowed, disapproving eyes, our little shop was a portal to hell itself. As for me, I was the worst possible sinner – an educated gentleman, a student of Divinity destined for the Church, who had chosen instead a life of vice. I might as well paint myself red and sprout horns.

Gonson thrust a hand in his bag and pulled out a slim volume. ‘One of our members bought this yesterday.’

The Society was unashamed in its use of ‘virtuous informers’, who visited brothels, molly houses and other places of ill repute such as the Pistol. It was the duty of all honest Christians to betray their neighbours, you understand.

‘Venus in the Cloister. It looks well thumbed,’ I noted, taking it from him. I opened it to a favourite illustration. ‘Was it necessary to inspect every page?’

One of the guards coughed back a laugh. Gonson frowned at him.

Venus in the Cloister is a stirring dialogue in which Sisters Agnes and Angelica describe – in commendable detail – their nightly exploits with their monkish lovers. It is tender, cheerful, and instructive to both men and women. I wish I had read it before my first adventures – it would have saved a good deal of awkward fumbling.

Gonson snatched his copy back. ‘I have never seen such blasphemy. Such obscenity.’

‘My condolences,’ I murmured.

Kitty elbowed me.

Gonson was too absorbed by his own outrage to notice. ‘I could have you pilloried for this.’

With that, I lost my sense of humour. A man could survive the pillory without a scratch, if the town had no desire to attack him. But if Gonson had me chained up in the square, then ordered members of the Society to throw mud and stones and worse at me for hours, they could easily kill me. Men had thrown stones at me before, when I was dragged to the scaffold. I still carried a scar upon my forehead from that day. Kitty touched the back of my hand with hers.

‘What is it that you want, Sir John?’ she asked, in a gentle voice. That surprised me. Kitty had many virtues, but meekness was not one of them. ‘This is my shop, not Tom’s. He is merely . . .’ she groped for a respectable word, ‘. . . my lodger.’

I stared at her.

‘I have prayed upon the matter, Miss Sparks,’ Gonson said, with a pious tilt of the head. ‘I have no wish to see you in chains, beating hemp like a common harlot.’ His eyes gleamed, imagining the scene. ‘I believe there is hope for you, child.’

Something rang false in his words. Too much sympathy, not enough censure. Gonson was a man of unflagging moral vigour. Sinners must be punished. Doubters must be corrected. How many women had he sent to gaol for selling themselves? How many men had been arrested or shamed over rumours of sodomy?

A lodger?

‘I could find a dozen men to testify that this is an honest business,’ I said.

‘No doubt,’ Gonson sneered. ‘Shameless devil. And I could send informers in here every day to spy upon you both. I could raid this place once a week. How long would your customers support you then, I wonder?’ He turned his attention back to Kitty. ‘But as I say, I have no desire to punish you, my child.’ He smoothed the bottom of his wig, and offered her a greasy smile. ‘I seek only your redemption.’

I folded my arms. ‘And while we wait for that glorious day?’

Gonson said nothing. He was still smiling at Kitty, in such a queer, covetous way that I wanted to shove him from the room. What was he about? He had met Kitty several times before and shown her nothing but contempt. She was always ‘strumpet’, ‘harlot’, ‘slut’ to him. Not child. In any case she was nineteen. A woman. My woman. He could not think of himself as my rival, surely? Good God. The notion would be comical, if it weren’t so nauseating.

‘Your salvation rests in your own hands, Miss Sparks,’ he said, in a portentous voice. ‘I shall return tomorrow morning, and expect to see a great heap of these foul books, ready for burning. We shall have ourselves a bonfire, a holy conflagration!’

‘We shall do no such thing,’ I snapped.

‘Tom . . .’ Kitty warned.

Gonson’s smile deepened. ‘This is your decision, child, and yours alone. Pray to God, and in His wisdom He will guide you.’ He bowed to her, and left with his men.

Oh, clever, I thought. He is trying to divide us, but it shall not work. Then I turned to Kitty, and caught her quiet, worried expression.

‘Kitty. No.’

‘We can buy more books. Or . . .’ She looked around at the shop she had worked so hard to build. ‘I can sell other things. I have plenty of capital.’

‘He was bluffing, Kitty. He has no power over us. Think of our customers!’ There was barely a single nobleman or judge who had not bought something from the Pistol, directly or indirectly.

Kitty was not convinced. ‘He’ll find a way. You know how determined he is, when he wants something.’

‘Precisely! You can’t appease a man like Gonson. If we do as he asks, he will only return and demand more and more from us. We must stand firm. Let him bellow and bluster all he likes – he won’t arrest us for selling books.’

‘That’s what Curll said.’

‘That is a decidedly different matter.’ Edmund Curll had spent the past year in prison for printing such noble works as The Use of Flogging and The Nun in her Smock. But Curll was a notorious rogue who published private letters without permission and copied the works of honest writers without sharing the profit. Worst of all, he sold false goods. I once paid three shillings for what he insisted was a volume of bawdy poems, only to discover, when I unwrapped the parcel at home, that I had bought a collection of sermons by the Bishop of Gloucester. Some villainies cannot be forgiven.

‘Damn Gonson,’ I muttered. ‘Sanctimonious arsehole.’

‘You provoke him, Tom.’

‘Oh! So this is my fault?’

‘I didn’t say that.’

‘You implied it.’

She frowned, distracted. ‘Let me think, please. Just let me think.’

‘What is there to think about?’ I grabbed the novel I had been reading. ‘We cannot burn books, Kitty!’

‘Tha. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...