- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Late spring, 1728 and Thomas Hawkins has left London for the wild beauty of Yorkshire - forced on a mission he can't refuse. John Aislabie, one of the wealthiest men in England, has been threatened with murder. Blackmailed into investigating, Tom must hunt down those responsible, or lose the woman he loves forever.

Since Aislabie is widely regarded as the architect of the greatest financial swindle ever seen, there is no shortage of suspects.

Far from the ragged comforts of home, Tom and his ward Sam Fleet enter a world of elegant surfaces and hidden danger. The great estate is haunted by family secrets and simmering unease. Someone is determined to punish John Aislabie - and anyone who stands in the way. As the violence escalates and shocking truths are revealed, Tom is dragged, inexorably, towards the darkest night of his life.

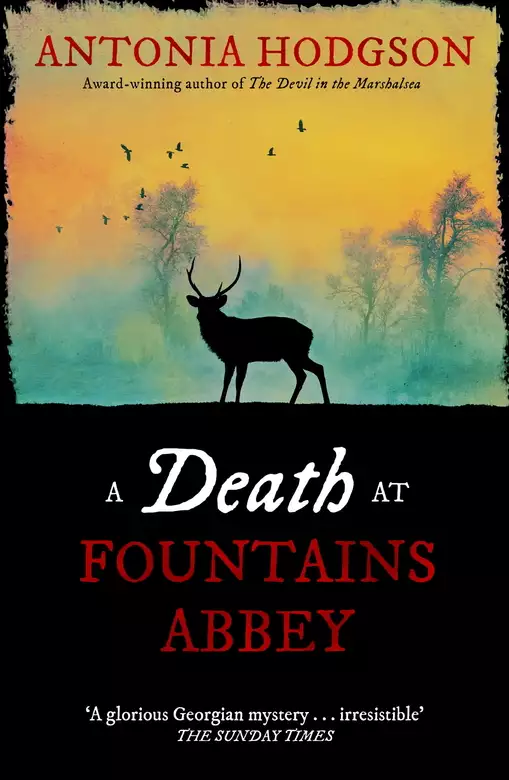

Inspired by real characters, events and settings, A Death at Fountains Abbey is a gripping standalone historical thriller. It also continues the story that began with the award-winning The Devil in the Marshalsea and The Last Confession of Thomas Hawkins.

Release date: August 25, 2016

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 420

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Death at Fountains Abbey

Antonia Hodgson

January, 1701

Red Lion Square, London

She never meant for the fire to spread. It was a distraction, nothing more, a trick to keep them busy while she took what she was owed. She had cried, ‘Fire! Fire in the attic!’, and laughed to herself as the house woke in panic. They pushed past her on the stairs, running to fetch water, to save what they could, coughing as the smoke caught their lungs.

She saw him too, clutching his daughter Mary to his chest as he carried her to safety. John Aislabie. He didn’t notice her as he passed, close enough to touch. He hadn’t noticed her for a long time.

She joined the flow of servants hurrying downstairs. When they ran out into the square, no one realised that Molly Gaining wasn’t with them any more.

She crept down the empty corridor to Mr Aislabie’s study, tiptoeing her way in the dark. It was the first duty of a housemaid to be silent. Invisible.

He had called her his treasure. He’d murmured promises to her in the deep night, vows he had never meant to keep. I will cover you with gold; I will wrap you in silks. She had believed him. She had given him everything he wanted. And when he was done, he’d tossed her aside, no longer his treasure but some sordid piece of rubbish he would never touch again.

She heard muffled shouts, somewhere high up in the house. Here inside his study, all was still, save for the ticking of the clock. She felt her way to the desk with no need for a lamp: she had swept and polished this room every day for the last five years. She opened a drawer, groping past quills and papers to find a key buried in one corner. Moving swiftly to the hearth, she splayed her fingers, searching for the loose floorboard she’d discovered a few days before. There. She lifted the board and reached inside, touching cold metal. A strongbox, so heavy she needed both hands to pull it free.

The key turned with a soft click. A shiver of illicit excitement thrilled through her. She must be quick, before the fire was tamed and she was discovered. She threw back the lid.

He had promised her gold, and diamonds. She would keep him to that promise.

She lifted out a handful of jewels, gold chains dangling between her fingers. Touch and memory showed her what her eyes couldn’t see in the dark: long strands of creamy white pearls, gold rings studded with precious stones, a diamond and ruby brooch that she could feel now, cool and heavy in her palm. Bags of gold coins. She tucked them into the wide pocket she had stitched beneath her gown, and reached for more. Enough for the life she had dreamed of. Enough for the life she deserved.

Voices, loud outside the door. She had lingered too long. Cursing under her breath, she threw another fistful of coins into her pocket and straightened her gown just as a young man pushed open the door and strode into the study. His face was handsome in the orange light of his candle, and full of purpose.

‘The account books. Hurry!’

Jack Sneaton: Aislabie’s clerk. She shrank back, praying he wouldn’t see her, while he gathered up books and papers, throwing them into the arms of his apprentice. Trust Jack. Of all the things to save from the fire, he runs for his precious tally books.

He turned for the door.

‘Sir?’ Sneaton’s apprentice nodded towards the hearth.

She was discovered. Fear pressed a fist into her heart.

Sneaton thrust a sheaf of papers into the boy’s arms. ‘Molly? What are you about down there—’ He stopped and stared in dismay at the coins and jewels glinting on the floor where she had spilled them in her haste. He blinked several times, very fast, as if hoping the scene might vanish before his eyes.

‘Thief!’ his apprentice hissed.

Sneaton winced, as if the accusation caused him physical pain. He took one last, studied look at the empty strongbox. Then he grabbed Molly by the arm and pulled her to her feet.

‘No!’ she cried, as he dragged her from the room. ‘I weren’t stealing, I swear. Please, Jack . . . Mr Sneaton, sir – I was saving them from the fire.’

He pressed his hand against the nape of her neck and pushed her through the house out on to the street. She stumbled on the steps and fell to the ground, crying out as a shard of glass pierced the plump flesh beneath her thumb. There was glass everywhere.

She crawled along the cobbles on her hands and knees, sucking in her breath as she pulled the glass free. Blood trickled down her wrist.

And, looking up, she saw what she had done.

The fire was raging from the top of the house, flames tearing across the roof and bursting through broken windows. Thick grey clouds of smoke billowed high above the flames, choking the night sky. A line of servants passed buckets of water up through the building as neighbours hurried to join them, desperate to stop the fire spreading further along the square.

A footman collapsed to his knees at the doorway, his face black with soot. He gulped a few breaths of clear air, grabbed a fresh bucket, and plunged back inside.

‘It was only a small fire,’ she whispered. She tottered forwards, drawn towards the flames. She could feel the immense heat of them on her face. ‘I never meant . . .’

Sneaton pulled her away. ‘Mr Aislabie. Mr Aislabie, sir!’

He was standing a few feet from them, closer to the burning house, still holding Mary in his arms. Jane, his younger daughter, was clinging to his leg. Both girls were mute with terror.

‘Mr Aislabie,’ Sneaton called again, and he turned, and saw them.

‘Molly,’ he said. ‘Thank God you’re safe.’

Misery and fury closed her throat. Now you look at me, John. Now you speak my name.

‘Found her in your room, sir,’ Sneaton said. ‘She was stealing from your strongbox.’

He stared at her.

‘I wasn’t thieving,’ she stammered. ‘I was trying to save them from the fire. You know me, sir . . .’

She saw a flicker of doubt in his eyes. ‘We’ll settle this later,’ he said, distracted by the flames. He lifted Mary to the ground and handed both girls to a neighbour. ‘Harry!’ he called out to one of his men, limping from the house. ‘Where’s Mrs Aislabie? Is she safe?’

Harry couldn’t speak from the smoke. He bent to the ground, wheezing as he took in the fresh air.

‘For heaven’s sake, man, where’s my son?’ Aislabie shouted, in a sudden panic. ‘Where’s Lizzie? Where’s my little girl?’

Harry shook his head.

For a second, Aislabie was too stunned to react. Then he spun about and ran blindly into the blazing house, calling their names. Anne. William. Lizzie.

‘Damn it!’ Sneaton cursed. He pushed Molly into his friend’s arms as if she were a bundle of dirty rags. ‘Keep a hold of her, Harry. She’s a bloody thief.’

Worse than that. She gazed up at the house, the flames rolling across the roof, the smoke pouring from every window. Lizzie, the youngest girl, only just learning to walk. Mrs Aislabie. William, the new baby. What had she done? An emptiness opened up inside her and her body felt light, as if she could drift up into the air and dissolve to nothing . . .

‘Molly!’ Sneaton’s voice broke the spell.

‘It was such a small thing, Jack. Such a small fire. I never meant . . .’

She never forgot it, the look Jack Sneaton gave her in that long, silent moment. ‘You were my jewel, Molly,’ he said, quietly.

The cobbles tilted beneath her feet. She never knew. He’d never told her. If she could just go back half an hour. That was all she needed to make things right again – just half an hour. But it was too late.

Sneaton snatched up a bucket and soaked his neckerchief in the water. ‘Where are they, Harry?’

Harry pointed to a window on the second floor. ‘You won’t reach it, Jack. The smoke’s terrible.’

Sneaton put the wet cloth to his mouth and ran inside.

Harry pulled her away. She stumbled along with him until they reached a ring of neighbours, clinging to each other in horror as the house burned down in front of them. They watched as Mr Aislabie was dragged out by his servants empty-handed, screaming his wife’s name. Saw the last few men beaten back by the smoke and flames.

‘Nothing to be done, now, God rest their souls,’ one of the neighbours said. ‘Just pray it doesn’t spread.’

Harry dug his fingers deeper into her shoulder.

Then someone gave a shout and pointed to a window on the second floor. ‘There! Look!’

Jack Sneaton stood at the window, clasping a tiny bundle to his chest. He clambered on to the ledge, smoke pouring all about him like a thick grey cloak. No way to clamber down, not from such a height. He gestured fiercely to the men below with his free hand. They gathered beneath him, huddled together. He raised the bundle carefully in both hands, then let go.

They caught it. Safe. A cheer rose up. Someone called to Mr Aislabie. ‘Your son! Mr Aislabie! Your son is saved!’

At the same moment a fresh burst of flames swept out through the window, engulfing Jack Sneaton. With a great cry, he dropped from the ledge and fell twenty feet to the ground.

‘Jack!’ Harry rushed forward to help his friend, forgetting her in his hurry. She couldn’t see Jack, but she could see men beating at the flames with their coats, and a man rushing forward with a bucket of water. She could hear screaming.

Molly glanced about her. None of the people standing around her knew what she had done. She was just another servant, caught up in the tragedy. The crowd surged forwards, anxious to see if the night’s hero had survived his fall. Mr Aislabie was holding his baby son, and weeping. Amidst the chaos, the shouts for aid, the men running back and forth with more water, Molly stood alone, forgotten.

She took one step away. Dared another.

No one stopped her.

No one even noticed her leave.

Numb, half blind from the smoke, she walked away. Beyond the press of spectators, the street had fallen eerily still. She drifted past the stone watch tower at the end of the square as if in a dream.

Behind Red Lion Square lay a dank alley. It was too narrow for the grander carriages, too muddy and noisome for the better folk to use. This was where the week’s coal was delivered, and the night soil was collected. And it was here that Molly Gaining stumbled now, weighed down with a pocket full of jewellery and gold coins. How long before she was missed? How far could she run, and where should she go?

She had reached the back entrance to Mr Aislabie’s home, burning as hard as the front. No one had thought to fight the fire from here. Or perhaps there were not men enough to spare. The flames had begun to spread along the roof to the neighbouring house. She thought of the Great Fire, the tales her father had told her of it tearing through the streets for days.

‘I never meant to hurt no one,’ she whispered, to the flames, to the smoke. The emptiness had returned, a hollow feeling deep in her chest. She didn’t know, yet, that it would never leave her.

As she stared at the house she had destroyed, she caught a glimpse of something small and pale shimmering at a window on the ground floor. And Molly knew – she knew – what it was.

Redemption.

Chapter One

John Aislabie was in trouble.

‘I believe my life is in danger,’ he wrote, in a letter to the queen dated the 22nd of February. And then, when he received no reply, again on the 6th of March. He reminded her of the great service he had performed on her behalf, the sacrifices he had made to ensure that the royal family’s honour – that the crown itself – had remained intact. He underscored the words honour and crown with a thick line, making the threat explicit. A determined man, to threaten the royal family. Determined and desperate.

The queen responded a week later. ‘We are sending a young gentleman up to Yorkshire to resolve the matter. We do not wish to hear from you again.’

It was a measure of Mr Aislabie’s poor standing at court that I was the young gentleman in question.

‘Mr Hawkins?’ The coachman jumped down from his seat, boots thudding on the cobbles.

I took my hands from my pockets and nodded in greeting. I had arrived in Ripon late the night before, taking a room at the Royal Oak rather than travel the last few miles to Aislabie’s house in the dark. After breakfasting this morning I had sent word of my arrival. The carriage had raced from Studley Hall within the half hour. Clearly my host was anxious to meet me.

I couldn’t return the compliment. I had travelled to Yorkshire at the command of Queen Caroline – a command presented as a gift. It would be pleasant, non, a short trip to the country? A chance to recover from your recent misfortunes? Fresh air and long walks? This from a woman who scarce moved from her sofa. I had declined the offer. The offer was transformed into a threat. So here I was, against my will, preparing to meet one of the most hated men in England.

John Aislabie had been Chancellor of the Exchequer during the great South Sea frenzy eight years before. He’d proposed the scheme in the House of Commons. At his encouragement, thousands had invested heavily in the company’s shares. After all, what could be more secure? Mr Aislabie had put his own money into the scheme. He had invested tens of thousands of pounds of King George’s money.

And for a few giddy months that summer, shares had exploded in value. Overnight, apprentices became as rich as lords. Servants abandoned their masters, owning stock worth more than they could earn in five lifetimes. Thousands more scrambled to join the madness as the price of shares rose hour by hour. In the coffeehouses of Change Alley, trading turned more lunatic by the day. Poets and lawyers, tailors and turnkeys, parsons and brothel women scooped up every last coin they could find and joined in the national madness.

Then the bubble burst, as bubbles do. The lucky few sold out in time, holding on to their fortunes. The rest were ruined, catastrophically so. How many took their own lives in despair, rather than face the consequences of their unimaginable debts? Impossible to say. But the South Sea Scheme had been the Great Plague of investment – and Mr Aislabie had spread the disease.

The nation shouted for justice. Aislabie was found guilty of corruption and thrown in the Tower. When the public mind had turned to other things, he was allowed to slink away to Studley Royal, his country estate. Bankrupt, he insisted. Scarce able to feed his poor family. Sacrificed to spare more noble-blooded men.

No one listened and no one cared.

I had been eighteen at the time, studying divinity at Oxford. I am a gambler to my marrow, but I did not have the funds to dabble in stockjobbing, having invested my father’s allowance in the more traditional markets of whoring and drinking. I had watched in astonishment and frustration as two of my friends built dizzying fortunes in a matter of weeks. One of them had been wise enough to sell his shares before the final subscription, leaving him with a profit of ten thousand pounds. The other, a young fellow named Christopher d’Arfay, lost everything. He joined the army soon after, and I never saw him again. But I thought of him on the road north. One life destroyed, among tens of thousands.

Mr Aislabie’s coachman was a cheerful, robust fellow named Pugh, his cheeks scarred from an ancient attack of smallpox. He must have been near fifty, but he picked up my large portmanteau as if it were empty, and swung it on to the carriage. ‘Expected you yesterday, sir.’

I rolled my shoulders, frowning as my spine cracked. My journey had lasted five lamentable days, bumping and jolting along in a series of worn-out coaches until every bone had been thoroughly rattled in its socket. I felt as if I were recovering from a rheumatic fit, I ached so much. ‘Bad roads,’ I said, though that was not the only reason for the delay.

Pugh grunted in sympathy. ‘I’ve drove Mr Aislabie up and down to London a fair few times. That stretch from Leicester to Nottingham could kill a man, it’s so poor. No better in spring than winter.’

‘Yes. Very poor.’ It is the nature of long, tedious journeys that – on arrival – they must be lived again, in long, tedious conversation. A simple: ‘I travelled. It was dreadful. Here I am,’ will not do, apparently.

Pugh tied a box to the back of the chaise. Books, tobacco, playing cards and dice. A brace of pistols. I had worn them at my belt on the road, in case of attack. I hoped I would not need to take them out again.

‘A young gentleman fell hard on the Nottingham road a few weeks ago,’ Pugh trundled on. ‘Broke his arm and his wrist, poor lad. I trust you didn’t take a fall along the way, sir?’

‘Thank you, no.’

He slotted the last of my boxes into place. ‘Glad to hear that, Mr Hawkins. You’ve suffered enough injury these past weeks, I’d say.’

I raised my hand to my throat on instinct, then dropped it swiftly. A few months ago my neighbour had been stabbed to death in his bed – the day after I had threatened to kill him. At my trial, the jury had judged me not upon the evidence, but upon my character and reputation. I was found guilty, and sentenced to hang. Against all odds I had survived – but only after I had spent ten long, agonising minutes dangling from a rope, suffocating slowly as a hundred thousand spectators cheered me on. Ever since then I had suffered from nightmares: the white hood thrust over my head, the cart pulling away beneath my feet, the rope tightening around my neck. These terrors filled my dreams, and in the day left me with a dull ache in my chest – a feeling of dread that I could not shake.

I was grateful beyond reason to be alive. There were times when the mere fact of my existence could lift me to ecstasy – as if I had knocked back three bowls of punch in one. But I had met with Death that day at the scaffold. I had crossed the border into his kingdom, if only for a few moments. I feared the experience had changed me for ever. I feared, in truth, that Death still kept a hand upon my shoulder.

My hope had been that my story would not have travelled as far as the Yorkshire Dales. In the retelling of that story, I had been transmuted from an idle rogue to a golden hero – a martyr, even. That was what they had been calling me in the London newspapers, when they believed me dead. I didn’t want to be a hero. Heroes were sent on secret missions by the Queen of England, when they would much rather sit in a coffeehouse getting drunk and singing ballads.

My dreams of remaining anonymous had been dashed at breakfast, when a serving maid had asked to touch my throat for luck. I’d shooed her from the room, but it had been a gloomy experience.

If she’d asked to touch your cock, you wouldn’t feel so gloomy. Kitty, in my head.

‘We’re ready to leave?’

‘We are, sir,’ Pugh replied, nodding towards the inn. ‘If you would call your wife.’

My wife. By which he meant Kitty, who was neither my wife, nor within calling distance. For the sake of Kitty’s good name, and to ensure a civil reception at Studley Hall, I had written in advance to Mr Aislabie, explaining that I would be accompanied on my visit by my wife, Mrs Catherine Hawkins. How wondrously respectable that sounded. Unfortunately I had not had the time nor the heart to write again further along the road to explain that my wife and I had quarrelled fearsomely at Newport Pagnell, resulting in Mrs Hawkins’ swift return to London.

‘Fuck off then, Tom,’ she had shouted, in the middle of the inn. ‘Fuck off to Yorkshire, and don’t blame me if you die in some horrific way, stabbed and burned and throttled and mangled. I shall not grieve for you, not for one second. I will jump on your grave and sing I told you so, Thomas Hawkins, you fucking idiot. You may count upon it.’

‘Mrs Hawkins was called home on urgent business.’

‘Sorry to hear that, sir. You’re travelling alone, then?’

Not quite. A dark figure slipped out from behind a rag-filled wagon. He was dressed in an ancient pair of mud-brown woollen breeches and a black coat, cuffs covering his knuckles. My black coat, in fact, which was several inches too big for him. His black curls were tied in a ribbon beneath a battered three-cornered hat.

‘And who’s this?’ Pugh asked, bending towards Sam as if he were a child. I had made the same mistake, the first time I’d met him. A boy of St Giles, raised in the shadows, smaller than he should be.

Sam’s eyes – black and fathomless – fixed upon mine.

‘This is Master Samuel Fleet.’ Son of a gang captain, nephew of an assassin. And at fourteen years of age, on his way to becoming more deadly than either. ‘I’m his guardian.’

Well. Someone had to keep a watch on him.

The town square was packed with stalls for the Thursday market, the air laced with the warm tang of wool and sheepskin. Traders and townsfolk recognised our coach and hurried to clear the way for us: Mr Aislabie’s standing was far greater here in his own county. He had been mayor of Ripon, many years ago, and his son was now the town’s representative in parliament. Such things command a degree of respect, if not love.

We were soon through the town and riding along a country lane banked with thick hedgerows. Our carriage was a fine, open chaise, pulled by four of the best horses I had ever seen. The sun gleamed upon their bay coats as they raced towards Mr Aislabie’s estate of Studley Royal, along a road they knew well and seemed to enjoy. Pugh gave us their names, and the names of their forefathers, and would have continued on if I had not distracted him with a query about the weather. He was the head groom at Studley, and most likely knew the horses’ ancestry better than his own. He was a garrulous fellow, and I learned swiftly that a response was neither required nor particularly welcome. He spoke in the way some men whistle, and it was best to leave him to it.

I settled back, enjoying the sunshine. Insects buzzed in the grass, sparrows pecked at the ground with short beaks, a blackbird sang out from the branches above our heads. All about us, left, right and onwards, the fields rose and dipped, seamed with dry-stone walls and hedges. A pleasant, spring green world, spreading out to the horizon.

Sam perched upon the opposite bench, watching it all with a mistrustful eye, as if the land might rise up and swallow him. I had grown up on the Suffolk coast with its quiet villages and endless skies. Sam was born and raised in London, happy in the stink and bustle of its worst slums. He knew every thieves’ alley, every poisonous gin shop, every abandoned cellar transformed into a makeshift brothel. He was street vermin, street filth, and proud of it.

A fat bumblebee buzzed between us. Sam froze – a boy who would face down a blade without blinking. ‘It won’t harm you,’ I murmured, so as not to embarrass him in front of Pugh. Sam lifted one shoulder, as if he couldn’t care less if it stung him repeatedly in the face, but he looked relieved when it drifted on its way.

Each morning of our journey north, Sam had clambered ahead of me into the carriage and taken the bench closest to the horses, facing backwards. This suited us both well enough: if we had sat side by side we would have rolled into one another at every sharp corner. But it was such a deliberate action that I had begun to suspect a deeper motive; Sam did not do such things upon a whim.

On the day of my hanging, I had been bound in chains and paraded through the streets on an open cart. Condemned prisoners ride backwards to the gallows. The journey had been terrifying: the crowds lining the streets, the mud flung at the cart, the hatred pulsing through the air. My own fear, sharp and solid as a stone in my throat. We must all travel blind to our deaths, but to feel its slow, creeping approach with every turn of the wheel is a horror beyond imagining.

The simple roll and pitch of a carriage could return me to that morning in a heartbeat. Somehow, Sam understood this and took the seat facing backwards in order to spare me. How he had come to guess at such a deep-buried feeling I couldn’t say – and there would be no profit in asking. I was lucky to squeeze ten words out of the boy in fifty miles. But we had travelled together four days in succession with no other company, facing one another as the carriage rumbled along. Perhaps he had simply read the truth in my eyes. It was an unsettling thought, that he had been watching me so carefully.

You can’t trust him, Tom. Kitty’s voice again in my head. You know what he is.

We had travelled no more than a quarter hour when I saw a boundary wall ahead, ten feet high and stretching off into the distance. The horses pulled harder with no need for the whip, eager to be home. ‘Is this Mr Aislabie’s estate?’

Pugh twisted in his seat. ‘One corner of it. It’s Aizelbee, sir.’ I’d pronounced it Ailabee – the French way.

I hunched lower in my coat. It was a bright morning, but there was a sharp wind blowing in from the east. Sam was sitting on his hands to keep them warm. Feeble city folk, the pair of us.

‘Will we pass Fountains Abbey?’ Fellow guests at the Oak had mentioned the ancient monastery at supper. According to the – somewhat biased – landlord, they were the largest and the most splendid ruins in the country. And haunted, naturally.

‘No, sir,’ Pugh replied, and fell silent for once.

We rode through the tiny village of Studley Roger. Sam released his hands and clung to the edge of the carriage, taking in every detail as we passed through the hamlet. The size of the windows, the shape of the chimneys. The doors left open to the fresh air. A couple of muddy lanes. But nothing familiar, not really. And no tavern, I noticed, mournfully. No rowdy coffeehouse, the air clogged with pipe smoke, the latest newspaper laid out upon the table.

‘Second house upon the left. How many geese in the yard?’

Sam blinked. ‘Seven.’

This was a game we had played along the road. At least, I had played it and Sam had humoured me. He’d been raised to remain alert to his surroundings. In the city slums, there were threats and opportunities lurking in every doorway. Information could earn a boy his supper, or save his life. But I suspected Sam had a particular talent for it, something he was born with: a precision of mind far beyond my own or anyone else’s, for that matter.

We arrived at an iron gate, decorated with a coat of arms and flanked by a pair of stone lodges. An old man hurried out from one of them, waving his hat in greeting as he pulled open the gate. We rode through at a brisk pace, on to an oak-lined avenue. Thick branches reached out across the path, forming a tangle of shadows beneath. The sun, filtered through the leaves, cast a soft green light upon our skin.

I smiled at Sam, thinking of the rookery of St Giles, where planks and ladders criss-crossed the rooftops, creating high pathways through the slums. ‘Like home.’

He frowned in disagreement.

‘Mr Aislabie plans to chop all these down,’ Pugh said, waving at the trees. ‘Limes are better for an avenue. They grow straight. Oaks grow gnarly.’ As we crested the hill he slowed the horses. ‘If you’d look behind you, sir.’

I turned to see a magnificent view, the long avenue of oaks leading straight back towards the gate. From here we could see the valley below and then, rising on a twin hill, the town of Ripon. Through some trick of perspective, it appeared as if one could reach out and steal it. The avenue had been laid out so that the cathedral crowned the view precisely.

Pugh was smiling, waiting for . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...