- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

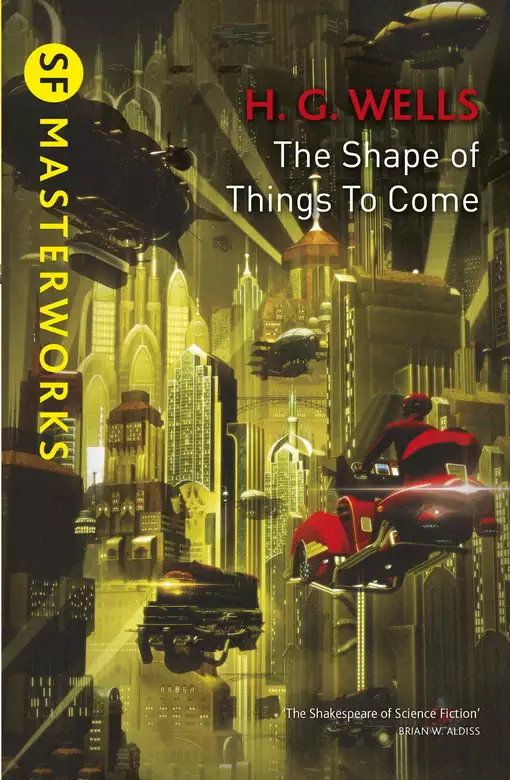

When Dr Philip Raven, a diplomat working for the League of Nations, dies in the 1930s, he leaves behind a book of dreams outlining the visions he has been experiencing for many years. These visions seem to be glimpses into the future, detailing events that will occur on Earth for the next two hundred years.

This fictional ''history of the future'' proved prescient in many ways, as Wells predicted events such as the Second World War, the rise of chemical warfare, climate change and the growing instability of the Middle East.

Release date: June 8, 2017

Publisher: Orion Publishing Group

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Shape Of Things To Come

H.G. Wells

Praise for The Shape of Things to Come

Title Page

Introduction

Introduction: The Dream Book of Dr Philip Raven

Book I Today and Tomorrow: The Age of Frustration Dawns

1.A Chronological note

2.How the idea and hope of the modern state first appeared

3.The accumulating disproportions of the old order

4.Early attempts to understand and deal with these disproportions: The criticisms of Karl Marx and Henry George

5.The way in which competition and monetary inefficiency strained the old order

6.The paradox of over-production and its relation to war

7.The Great War of 1914–1918

8.The impulse to abolish war: The episode of the Ford Peace Ship

9.The direct action of the Armament Industries in maintaining war stresses

10.Versailles: Seedbed of disasters

11.The impulse to abolish war: Why the League of Nations failed to pacify the world

12.The breakdown of ‘Finance’ and social morale after Versailles

13.1933: ‘Progress’ comes to a halt

Book II The Days After Tomorrow: The Age of Frustration

1.The London conference: The crowning failure of the old governments: The spread of dictatorships and fascisms

2.The sloughing of the old educational tradition

3.Disintegration and crystallization in the social magma: The gangster and militant political organizations

4.Changes in war practice after the World War

5.The fading vision of a World Pax: Japan reverts to warfare

6.The Western grip on Asia relaxes

7.The modern State and Germany

8.A note on hatred

9.The last war cyclone, 1940–1950

10.The raid of the germs

11.Europe in 1960

12.America in liquidation

Book III The World Renascence: The Birth of the Modern State

1.The plan of the Modern State is worked out

2.Thought and action: The new model of revolution

3.The technical revolutionary

4.Prophets, pioneers, fanatics and murdered men

5.The first conference at Basra: 1965

6.The growth of resistance to the Air and Sea Control

7.Intellectual antagonism to the Modern State

8.The second Conference at Basra, 1978

9.‘Three courses of action’

10.The Lifetime Plan

11.The real struggle for government begins

Book IV The Modern State Militant

1.Gap in the text

2.Melodramatic interlude

3.Futile insurrection

4.The schooling of mankind

Editor’s Note

5.The text resumes: The tyranny of the Second Council

6.Aesthetic frustration: The notebooks of Ariston Theotocopulos

7.The declaration of Mégève

Book V The Modern State in Control of Life

1.Monday morning in the creation of a new world

2.Keying up the planet

3.Geogonic planning

4.Changes in the control of behaviour

5.Organization of plenty

6.The average man grows older and wiser

7.Language and mental growth

8.Sublimation of interest

9.A new phase in the history of life

Also by H. G. Wells

About the Author

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

It’s always important to be aware of when a book was produced; for The Shape of Things to Come, it’s vital. It was published in September 1933, when the world was dealing with a number of crises – and the foreshadowings of huger crises to come. It responds to a number of then-current events: for instance, Franklin Roosevelt’s Presidency, which had begun earlier that year, as had Hitler’s Chancellorship of Germany. What it presents is nothing less than an imagined future history through to the year 2106, supposedly transmitted to the writer via a friend’s dreams: these dreams purport to give the friend the experience of reading a book of history written in the future. Records of these dreams – of this history book – constitute the body of The Shape of Things to Come.

The book occupies a peculiar place in the career of H. G. Wells (1866-1946). Almost all the science fiction works for which he became famous were published within a short span of time, when he was relatively young: for instance The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898), and The First Men in the Moon (1901). Over the decades after these, Wells became known for non-science-fiction work such as Tono-Bungay (1909) and The History of Mr Polly (1910), and for his enormous productivity as a writer of non-fiction. Particularly after the success of The Outline of History (1920), he became what we’d now think of as a public intellectual, someone with a shaping vision of how the world was and how it ought to be. The Shape of Things to Come is arguably the grandest synthesis of the two elements of Wells: the science fiction writer and the historical theorist.

A future history of this kind was not unprecedented in science fiction, but The Shape of Things to Come has far more successors than predecessors. Probably the most well-known earlier work in the same vein was Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men (1930), which charted a future for humanity through many millions of years and ultimately across a number of augmentations of the species through genetic modification. Put in that context, Wells’s frame – running until 2106 – seems relatively unambitious. But I think his purpose is rather different. Stapledon wants to examine as fully as possible the potential of humanity: what bodily and mental forms it might take, what its emotional and intellectual life might be like. Wells’s concerns are more immediate: politics, culture, and the organization of the state. It’s here that his skill as a science fiction writer becomes evident. The working out of his future societies, and the changes they undergo, is enormously detailed and fluent. The reader’s questions about how they operate or change are anticipated so often that the book comes to seem almost uncanny. But, of necessity, the framing of the book as a future work of history requires Wells to go into some detail about the prospects of the political figures of 1933. This is where the contemporary reader may have some problems – for instance, with his description of ‘that forcible, worthy, devoted and limited man, the Georgian, Stalin’, or with the judgment of Hitler as a less important figure than Mussolini.

That raises the question of prediction. Is The Shape of Things to Come to be judged harshly because it gets some things wrong? Or should it be commended because it gets some things right – for instance, the prospect of a European war flaring in 1940 because of a confrontation between Germany and Poland? The first thing to say on this question is any attempt at prediction will no doubt be proved wrong somehow. Wells’s opinions on the immediate future should, I’d suggest, be read as extrapolations of the information he had about the world in 1933. One can argue that he saw the major trends correctly – particularly the upsurge in European nationalism – but not how they would work out in detail. But the main burden of the book is not what happens in the 1930s and 40s. Instead, Wells is concerned with the new shapes society takes as a result of its immediate traumas. He envisages chaos mounting until the 1950s, after which a new ‘Dictatorship of the Air’ restores a kind of order. This too is overthrown after many years by a new society that seems – at least within the frame of the book – almost utopian. Two quotations from near the end of the book encapsulate the axioms from which Wells is proceeding. Firstly, it’s asserted that, ‘The immense developments and disasters of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries show us mankind scrambling on the verge of irreparable disaster.’ However, in describing the future state that has emerged, it’s said that, ‘The body of mankind is now one single organism of nearly two thousand five hundred million persons, and the individual differences of every one of those persons is like an exploring tentacle thrust out to test and to learn, to savour life in its fullness and bring in new experiences for the common stock. We are all members of one body.’ The reader who thinks this sounds like a kind of species-level socialism, with personal desires and wishes submerged, might be right: ‘Our Modern State has neither absorbed nor destroyed individuality which now, accepting the necessary restrictions upon its material aggressiveness, resumes at every opportunity its freedom and enterprise upon a higher level of life.’ So it’s not – at least as Wells frames it – that individuality has been wiped out, but rather that it’s willingly absented itself from much of human life. And, in many respects, the state as we understand it has also withered away by this point. So many sf utopias, particularly in the US tradition, proceed from libertarian axioms that it’s very striking to see one taking such a different point of view. Moreover, Wells sets out the nature of his society in such detail that one can understand fully the arguments underlying it: what it means for education, say, or religion. The Shape of Things to Come amounts to an argument about what society should aspire to in the light of its nineteenth and twentieth-century disasters, and it invites the reader to argue back.

It should be said, also, that some of the views embodied in the book will be difficult for modern readers to read without concern. For instance, from early on in the narrative:

Later on (in England, America, Scandinavia, Germany, Finland, e.g.) in just the same way a majority of dissatisfied and aggressive women struggling for a role in affairs inflicted the vote upon the indifferent majority of women. But their achievement ended with that. Outside that sexual vindication, women at that time had little to contribute to the solution of the world’s problems, and as a matter of fact they contributed nothing.

Wells had written works which, in their time, were seen as anticipating some of feminism’s concerns, such as Ann Veronica (1909); and, later in The Shape of Things to Come, female characters such as Elizabeth Horthy and Jean Essenden do play a significant role. But at the time in the book that this assertion about women is raised, there’s no countervailing argument or evidence presented; because of Wells’s narrative strategy, this extract from the history book remains for the reader to challenge. (The same might be said of the film Things to Come made in 1936 from Wells’s screenplay.)

But, I’d argue, the best relationship a reader can have with this book is to respond to its provocations and challenges. Seemingly on every page there are arresting phrases or surprising reversals of perspective. The real achievement of a successful future history is if it convinces the reader that the world they live in is not the only one available to them. The Shape of Things to Come passes that test magnificently. I’m writing this at the end of 2016, a year that has seen considerable political upheaval in many countries, and that has provoked comparisons to the instability of the 1930s. Plenty of 2016’s pundits aspire to Wells’s charismatic certainty in telling readers how things may turn out – for good or for bad. But the most arresting thing about Wells’s future is that, by taking the long view, he is able to find a way through turmoil to a new way of structuring society. Indeed, he suggests that the ingredients of that future are already present. You may not agree with the remedies he proposes towards the end of the book. However, it’s hard not to be moved by a work written at a time of crisis but bearing the author’s message of radical hope.

Graham Sleight, December 2016

INTRODUCTION: THE DREAM BOOK OF DR PHILIP RAVEN

The unexpected death of Dr Philip Raven at Geneva in November 1930 was a very grave loss to the League of Nations Secretariat. Geneva lost a familiar figure – the long bent back, the halting gait, the head quizzically on one side – and the world lost a stimulatingly aggressive mind. His incessant devoted work, his extraordinary mental vigour, were, as his obituary notices testified, appreciated very highly by a world-wide following of distinguished and capable admirers. The general public was suddenly made aware of him.

It is rare that anyone outside the conventional areas of newspaper publicity produces so great a stir by dying; there were accounts of him in nearly every paper of importance from Oslo to New Zealand and from Buenos Aires to Japan – and the brief but admirable memoir by Sir Godfrey Cliffe gave the general reader a picture of an exceptionally simple, direct, devoted and energetic personality. There seems to have been only two extremely dissimilar photographs available for publication: an early one in which he looks like a blend of Shelley and Mr Maxton, and a later one, a snapshot, in which he leans askew on his stick and talks to Lord Parmoor in the entrance hall of the Assembly. One of his lank hands is held out in a characteristic illustrative gesture.

Incessantly laborious though he was, he could nevertheless find time to assist in, share and master all the broader problems that exercised his colleagues, and now they rushed forward with their gratitude. One noticeable thing in that posthumous eruption of publicity was the frequent acknowledgements of his aid and advice. Men were eager to testify to his importance and resentful at the public ignorance of his work. Three memorial volumes of his more important papers, reports, memoranda and addresses were arranged for and are still in course of publication.

Personally, although I was asked to do so in several quarters, and though I was known to have had the honour of his friendship, I made no contribution to that obituary chorus. My standing in the academic world did not justify my writing him a testimonial, but under normal circumstances that would not have deterred me from an attempt to sketch something of his odd personal ease and charm. I did not do so, however, because I found myself in a position of extraordinary embarrassment. His death was so unforeseen that we had embarked upon a very peculiar joint undertaking without making the slightest provision for that risk. It is only now after an interval of nearly three years, and after some very difficult discussions with his more intimate friends, that I have decided to publish the facts and the substance of this peculiar cooperation of ours.

It concerns the matter of this present book. All this time I have been holding back a manuscript, or rather a collection of papers and writings, entrusted to me. It is a collection about which, I think, a considerable amount of hesitation was, and perhaps is still, justifiable. It is, or at least it professes to be, a Short History of the World for about the next century and a half. (I can quite understand that the reader will rub his eyes at these words and suspect the printer of some sort of agraphia.) But that is exactly what this manuscript is. It is a Short History of the Future. It is a modern Sibylline book. Only now that the events of three years have more than justified everything stated in this anticipatory history have I had the courage to associate the reputation of my friend with the incredible claims of this work, and to find a publisher for it.

Let me tell very briefly what I know of its origin and how it came into my hands. I made the acquaintance of Dr Raven, or, to be more precise, he made mine in the closing year of the war. It was before he left Whitehall for Geneva. He was always an eager amateur of ideas, and he had been attracted by some suggestions about money I had made in a scrappy little book of forecasts called What is Coming? published in 1916. In this I had thrown out the suggestion that the waste of resources in the war, combined with the accumulation of debts that had been going on, would certainly leave the world as a whole bankrupt, that is to say it would leave the creditor class in a position to strangle the world, and that the only method to clear up this world bankruptcy and begin again on a hopeful basis would be to scale down all debts impartially, by a reduction of the amount of gold in the pound sterling and proportionally in the dollar and all other currencies based on gold. It seemed to me then an obvious necessity. It was, I recognize now, a crude idea – evidently I had not even got away from the idea of intrinsically valuable money – but none of us in those days had had the educational benefit of the monetary and credit convulsions that followed the Peace of Versailles. We were without experience, it wasn’t popular to think about money, and at best we thought like precocious children. Seventeen years later this idea of appreciating gold is accepted as an obvious suggestion by quite a number of people. Then it was received merely as the amateurish comment of an ignorant writer upon what was still regarded as the mysterious business of ‘monetary experts’. But it attracted the attention of Raven, who came along to talk over that and one or two other post-war possibilities I had started, and so he made my acquaintance.

Raven was as free from intellectual pompousness as William James; as candidly receptive to candid thinking. He could talk about his subject to an artist or a journalist; he would have talked to an errand boy if he thought he would get a fresh slant in that way. ‘Obvious’ was the word he brought with him. ‘The thing, my dear fellow’ – he called me my dear fellow in the first five minutes – ‘is so obvious that everybody will be too clever to consider it for a moment. Until it is belated. It is impossible to persuade anybody responsible that there is going to be a tremendous financial and monetary mix-up after this war. The victors will exact vindictive penalties and the losers of course will undertake to pay, but none of them realizes that money is going to do the most extraordinary things to them when they begin upon that. What they are going to do to each other is what occupies them, and what money is going to do to the whole lot of them is nobody’s affair.’

I can still see him as he said that in his high-pitched remonstrating voice. I will confess that for perhaps our first half-hour, until I was accustomed to his flavour, I did not like him. He was too full, too sure, too rapid and altogether too vivid for my slower Anglo-Saxon make-up. I did not like the evident preparation of his talk, nor the fact that he assisted it by the most extraordinary gestures. He would not sit down; he limped about my room, peering at books and pictures while he talked in his cracked forced voice, and waving those long lean hands of his about almost as if he was swimming through his subject. I have compared him to Maxton plus Shelley, rather older, but at the first outset I was reminded of Svengali in Du Maurier’s once popular Trilby. A shaven Svengali. I felt he was foreign, and my instincts about foreigners are as insular as my principles are cosmopolitan. It always seemed to me a little irreconcilable that he was a Balliol scholar, and had been one of the brightest ornaments of our Foreign Office staff before he went to Geneva.

At bottom I suppose much of our essential English shyness is an exaggerated wariness. We suspect the other fellow of our own moral subtleties. We restrain ourselves often to the point of insincerity. I am a rash man with a pen perhaps, but I am as circumspect and evasive as any other of my fellow countrymen when it comes to social intercourse. I found something almost indelicate in Raven’s direct attack upon my ideas.

He wanted to talk about my ideas beyond question. But at least equally he wanted to talk about his own. I had more than a suspicion that he had, in fact, come to me in order to talk to himself and hear how it sounded – against me as a sounding-board.

He went on to discuss various other collateral suggestions of mine, which were also, he said, of the ‘obvious’ class. He offered me a series of flattering insults. He said he found a certain mental simplicity I possess very refreshing. He was being tormented by the way things were going behind the fronts – and behind the scenes. Everybody, he declared, was busy fighting the war or planning to best our enemies or allies after the war; everybody was being so damned subtle that they were forgetting every clear realization they had ever had, and nobody, with the exception of a few such onlookers and outsiders as myself, was putting in any time in working out the broad inevitabilities of the process. With these others it is always what trick X will play next, and what will be Y’s dodge, and whether the Zs will stand this, that, or the other thing that is put upon them – if it is put in this, that, or the other way to them. But, of course, none of this was essential. In the long run only the essentials mattered.

‘In the long run,’ said I.

‘In the long run. And not such a very long run either in these days.’

I accepted that.

Gradually I warmed to his intellectual glow. What were the essentials? On that issue I was as keen as, if less outspoken than, he. ‘What is really happening now?’ I asked.

‘Yes,’ he agreed, in manifest delight. ‘What is really happening now? Damn them! Not one of them asks that question. That’s where you are so good, that’s where you are worthwhile. The others all think they know so well that they can afford to be shut and sly about it. They can’t.’

He called me then a Dealer in the Obvious, and he repeated that not very flattering phrase on various occasions when we met. ‘You have,’ he said, ‘defects that are almost gifts: a rapid but inexact memory for particulars, a quick grasp of proportions and no patience with detail. You hurry on to wholes. You have to see things simply or you could not see them at all. Consequently you cannot endure any conventional elaborations, any sideshows, needless complexities, indirect methods, diplomacies, legal fictions and tactful half-statements. It’s a joy to rattle on to you and feel there’s no complications. It isn’t, I think, that you have the power to take up all those things in your stride; I won’t flatter you like that; no – but you have the intuitive sense to drop them in your stride. There’s the secret of your simplicity; you come as near stupidity as wisdom can. How men of affairs must hate you – if and when they hear of you! They must think you an awful mug, you know – and yet you get there! Complications are their life. You try to get all these complications out of the way. You are a stripper, a damned impatient stripper. I would be a stripper too if I hadn’t the sort of job I have to do. But it is really extraordinarily refreshing to spend these occasional hours stripping events in your company.’

The reader must forgive my egotism in quoting these comments upon myself; they are necessary if my relations with Raven are to be made clear and if the spirit of this book is to be understood. I met him upon an unusual side that he could afford to reveal to very few other persons. That is my point. ‘If I generalized to other people as I do to you,’ he said, ‘if I talked as plainly, my reputation as an expert would go up – like a battleship hit in the magazine.’

I was, in fact, an outlet for a definite mental exuberance of his which it had hitherto distressed him to suppress. In my presence he could throw off Balliol and the Foreign Office – or, later on, the Secretariat – and let himself go. He could become the Eastern European Cosmopolitan he was by nature and descent. I became, as it were, an imaginative boon companion for him, his disreputable friend, a sort of intelligent butt, his Watson. I got to like the relationship. I got used to his physical exoticism, his gestures. I sympathized more and more with his irritation and distress as the Conference at Versailles unfolded. My instinctive racial distrust faded before the glowing intensity of his intellectual curiosity. We found we supplemented each other. I had a ready unclouded imagination and he had knowledge. We would go on the speculative spree together.

Finally it may be he started out to take me on the greatest speculative spree of all. I am quite open to the idea that this book is nothing more than that. It is well to bear that in mind in weighing what I have next to tell about this anticipatory History of his.

Among other gifted and original friends who, at all too rare intervals, honour me by coming along for a gossip is Mr J. W. Dunne, who years ago invented one of the earliest and most ‘different’ of aeroplanes, and who has since done a very considerable amount of subtle thinking upon the relationship of time and space to consciousness. Dunne clings to the idea that in certain ways we may anticipate the future, and he has adduced a series of very remarkable observations indeed to support that in his well-known Experiment with Time. That book was published in 1927, and I found it so attractive and stimulating that I wrote about it in one or two articles that were syndicated very extensively throughout the world. It was so excitingly fresh.

And among others who saw my account of this Experiment with Time, and who got the book and read it and then wrote to me about it, was Raven. Usually his communications to me were the briefest of notes, saying he would be in London, telling me of a change of address, asking about my movements, and so forth; but this was quite a long letter. Experiences such as Dunne’s, he said, were no novelty to him. He could add a lot to what was told in the book, and indeed he could extend the experience. The thing anticipated between sleeping and waking – Dunne’s experiments dealt chiefly with the premonitions in the dozing moment between wakefulness and oblivion – need not be just small affairs of tomorrow or next week; they could have a longer range. If, that is, you had the habit of long-range thinking. But these were days when scepticism had to present a hard face to greedy superstition, and it was one’s public duty to refrain from rash statements about these flimsy intimations, difficult as they were to distinguish from fantasies – except in one’s own mind. One might sacrifice a lot of influence if one betrayed too lively an interest in this sort of thing.

He wandered off into such sage generalizations and concluded abruptly. The letter had an effect of starting out to tell much more than it did. ‘Are you coming through Geneva on your way to Italy?’ it wound up. ‘If so, we might talk.’

When, however, I talked to him in Geneva – it was hot and we took a motor launch and had dinner at a pleasant restaurant on the lake shore beyond the waterspout – he would say scarcely a word about any glimpses he had had into futurity. He was dull and depressed that day. I never found out exactly what it was had robbed him of his customary exuberance. I asked him at last outright whether he hadn’t something to tell me about seeing into the future. He seemed to have forgotten his letter altogether. ‘What is there to see in the future?’ he asked, hunched in his chair. ‘I haven’t the guts for it.

‘These people here mean nothing,’ he vouchsafed. ‘Nothing at all.’

Afterwards we fell talking about the speculative boom that was then at its height in America. He said it was essentially an inflation of credit by bulling securities. While it lasted there would be a kind of prosperity, but there was nothing behind it but faith. At any time someone might start a selling that would collapse the whole thing. ‘And once they start a collapse over there . . .’

He let a grimace and a gesture of his lean long hand finish his sentence.

‘It’s a card castle,’ he said, and then with the groan of a tired man: ‘I can’t even find a metaphor today. It’s a card castle that will fall – like ten million tons of bricks.’

And I remember another sentence of his.

‘What I cannot understand is the levity of human beings – their incurable levity. This Geneva is the home of Calvinism. I used to think the Calvinists at least had some conception of the seriousness of life.’

He shook his head slowly and suddenly a gleam of humour lit up his sombre eyes for a moment. ‘It was liver,’ he said. ‘Everyone who comes to Geneva gets liver.’

‘So that’s what’s the matter!’ said I.

‘Liver and lethargy. Predestination. Do nothing. Attempt nothing. And burn any heretic who attempts salvation by works . . . You hope by nature, you know. It’s just the luck of your glands. They would have burnt you here without hesitation three centuries ago.’

Between endocrines and theology, whatever experiments with time he had been making were forgotten.

Afterwards I thought of the Dunne idea again, and I connected it so little with Raven’s abortive confidences that I made up a short story, Brownlow’s Newspaper, about a man into whose hands there fell an evening journal of fifty years ahead – and of all the tantalizingly incomplete intimations of change, such a scrap of the future would be sure to convey. Brownlow, whom I imagined as a cheerful and self-indulgent friend, came home late and rather alcoholic, and found this paper stuck through his letter-slit in the place of his usual Evening Standard. He found the print, paper and spelling rather queer; he was surprised by the realism of the coloured illustrations, he missed several familiar features, and he thought the news fantastic stuff, but he was too tired and muzzy to see the thing in its proper proportions, and in the morning when he awoke and thought about it, and realized the marvellous glimpse he had had into the world to come, the paper had vanished for ever down the dust-chute. This story was published in a popular magazine – the Strand Magazine, if I remember rightly – and Raven saw it. He wr

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...